by Elana Hagler

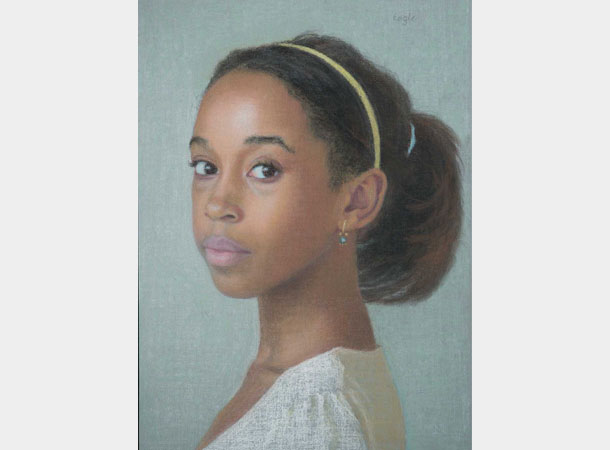

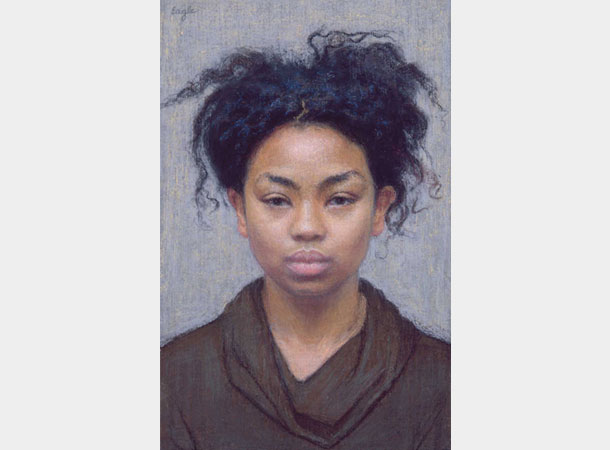

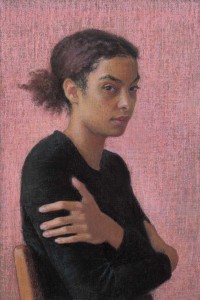

Ellen Eagle, Portrait of the Young Artist Marela Alvarez 2, 12 1/4 x 9 in. pastel on pumice board, image courtesy of the Forum Gallery

In his essay on Degas in The Shape of a Pocket, John Berger transforms Degas’ name into a verb:

Do we not all dream of being known, known by our backs, legs, buttocks, shoulders, elbows, hair? Not psychologically recognized, not socially acclaimed, not praised, just nakedly known. Known as a child is by its mother.

One might put it like this. Degas left behind something very strange. His name. His name, which, thanks to the example of his drawings, can now be used as a verb. ‘Degas me. Know me like that! Recognise me, dear God! Degas me.’[1]

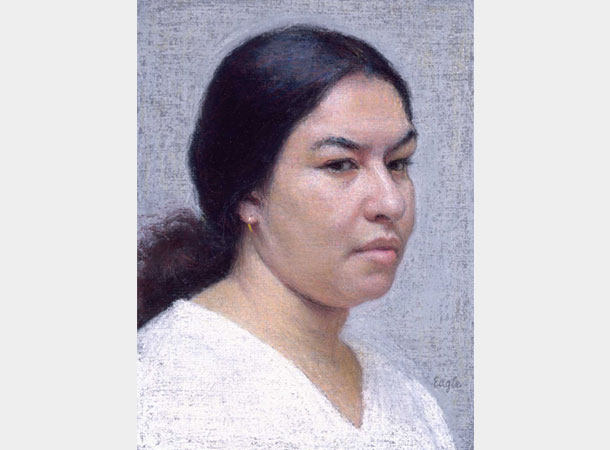

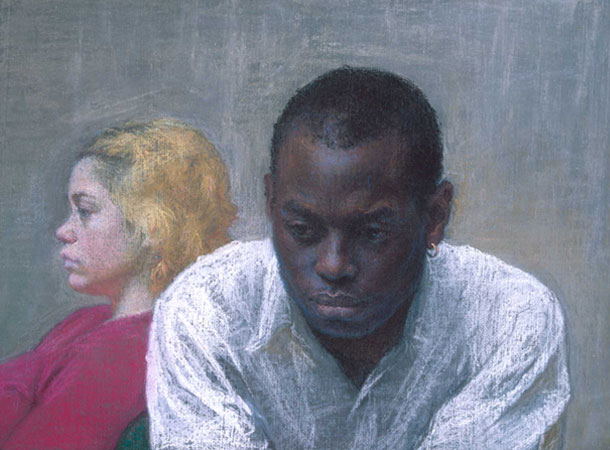

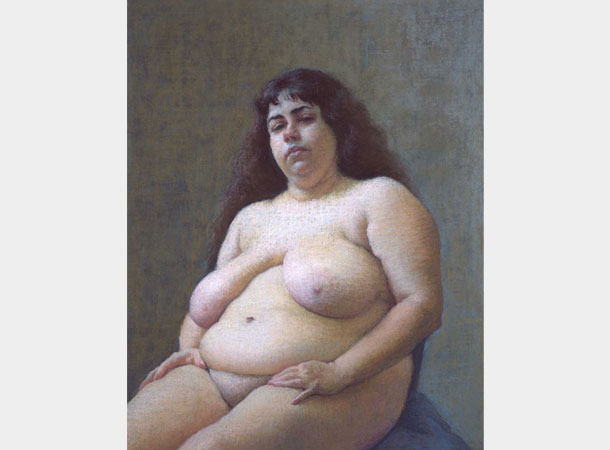

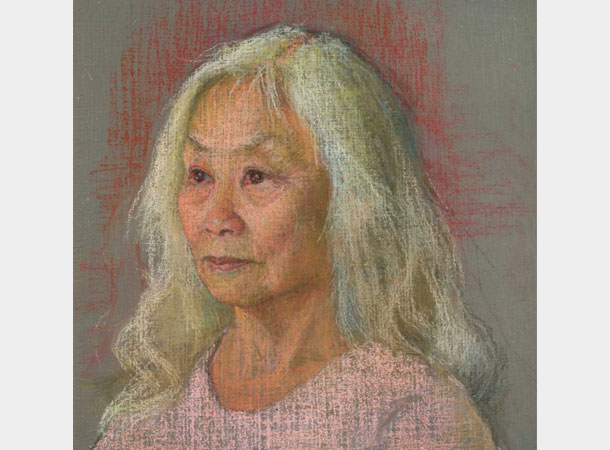

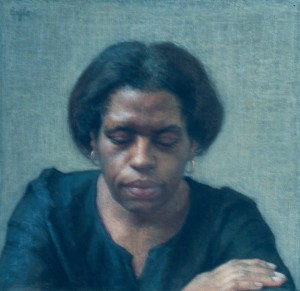

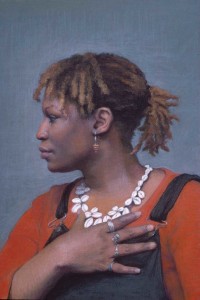

This quote comes immediately to mind when I look at Ellen Eagle’s exquisite pastel paintings. Each artwork feels like a fresh encounter with a very specific person at a very specific moment in his or her life. I intuit that this individual has been truly, intimately, profoundly seen by the painter and this deep knowing is transferred to me as the viewer through the magic of strokes of granular pigment interwoven on pumice board. And yet, at the same time, I am confronted by the unknowability of this person presented before me, an entire universe within this other whose internal world is shrouded in mystery. My experience of Ellen Eagle’s paintings is that of holding these contradicting sensations simultaneously in the moment of apprehension: I both marvel at the inscrutability and delight at the sense of intimate familiarity.

In preparation for this interview, I poured over Eagle’s 2013 book, Pastel Painting Atelier: Essential Lessons in Techniques, Practices, and Materials. As the title promises, there is indeed a large amount of practical advice contained within, and it is invaluable to anyone working in pastel. I, as an oil painter, was more interested in all of those pictorial values that translate across mediums and enjoyed reading her thoughts on gesture, composition, problem-solving, holding onto the first impression, and so on. This “shop talk” is graced throughout the book with insightful little gems, such as “My bliss animates my strokes” and “I seek the emergence and full crystallization of harmony.”[2]

It is a pleasure to interview Ellen Eagle here, and dig a little deeper into her work and her thoughts. Thank you so much for joining us, Ellen.

Ellen Eagle: Thank you so much for inviting me, Elana.

Elana Hagler: Let’s begin by finding out a little about your early path. Did you come from an artistic family? How did you come to painting? Were there any particular obstacles in your way?

EE: Yes, it is a gift to have come from a very artistic family. My mother was a professional pattern maker and clothing designer. She also created stunning and intricate embroidery, knit, and made curtains and furniture slipcovers. She did all things textile. She made dresses and pocketbooks for me and for my dolls. She painted with watercolor and oil, and, later in life, created very complex decoupages. She made my wedding dress, first making the pattern right on me. She was a perfectionist in all she did. If she went to bed unhappy with a stitch she had made in her embroidery or sewing, she got out of bed to restitch. Whatever she did, she did with the utmost integrity and respect. She frequently told me that she so wanted to be an artist that she gave birth to one.

My father’s artistry was with music and language. He had a beautiful singing voice, and the heart to sing. He seemed to know everything about opera and classical music, which he brought into our home, along with experimental music via radio programs that he sought out, and folk music in the tradition of Woody Guthrie and The Weavers. He also had a most poetic way with words; he had his very own unique way of expressing ideas, and he had an artist’s love of nature. At home, there was always music playing on the record player and radio. My parents were very curious about dance, theater, and music of other cultures, as well. Intrinsic to my parents’ artistic natures was a strong sense of humanism, of tenderness and compassion. My father cared about every child and animal and plant. My parents joined a record club for my brother when he was an infant. Recordings of all sorts of music were delivered to him, I think monthly. At a young age he became a working musician whose early recordings continue to garner respect and a growing following. He continues to write and perform widely today; his instruments are the guitar and voice. My cousins, too, are artists: one is an Emmy Award winning director/producer; his brother masterfully plays almost every musical instrument imaginable, and was the Manager of Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, and their third brother is a brilliant sculptor. Another cousin, now deceased, was a playwright/poet/actress/painter. When I was about ten, I brought a set of art supplies to my father’s father who was then in his 80s, I believe. Thus began his pursuit of artmaking, and he was very good. He was a man of peace, and he began to make paintings of newspaper images of war victims, in the tradition of Käthe Kollwitz.

How did I come to painting? From a very young age, I was absolutely captivated by the reproductions of paintings and sculptures in my parents’ art books. I was fascinated that the images provoked powerful emotion in me. At the time, I was too young to understand why certain images caused pleasure and others left me cold or uncomfortable, but I could not get enough of looking at the works, and wondering about them. Stirring within me in a nebulous way was the first awareness of the balance of excitement and discipline in the creation of a painting or sculpture. The first drawing I remember doing was of a small ceramic bird that perched on a desk in the living room. I was four. My mother saw the drawing on the desk and assumed that my brother, who was eleven, had done it. David told her “No, it must have been Ellen.” From that moment on, my mother made sure I had art supplies and was enrolled in art classes. My first art class was taken at the Staten Island Museum.

I quickly favored drawing portraits and figures over ceramic birds. I drew my friends and family. My father had a small clothing store in a working class immigrant neighborhood. Many of the neighbors did not speak English. I was at the store on Saturdays, when my mother also worked there. I stared at the faces and postures of the neighbors of various ethnicities and colors, and pondered their thoughts, because I did not understand their words. Little did I know it at the time, but I think this exposure set the stage for my lifelong fascination with wordless visual expression.

I can honestly say that I had very few, if any, obstacles, other than at grade school age, where I had writing teachers, drama teachers and music teachers who were more punishing than encouraging of creativity and independent initiative. One writing teacher failed me on a composition assignment, accusing me of having my brother write it for me. I also had a similar problem with a piano teacher. Such accusations and punishments filled me with shame. Fortunately, there were also many wonderful and supportive “noticers” of my abilities, who gave me tremendous encouragement. In junior high school, I had difficulty with math. My math teacher, Mr. Berman, was warm and kind towards me, despite my struggle. As if to counterbalance the writing teacher disaster, upon seeing some of my portrait drawings displayed in the school hallway one day, Mr. Berman entered the classroom of a different subject in which I was enrolled, and announced to me and the class that he sees a great talent in me. That he went to the trouble of finding out which classroom I was in at the moment, and to make a public statement of kindness and support alleviated the sting of my writing teacher, and has remained in my memory all these years. Eventually, my mother started taking me into New York’s Art Students League children’s class, and to a wonderful piano teacher on the Upper West Side. These were great escapes for me. And when I was eleven, my brother was attending City College of New York, within whose Harlem campus resided the High School of Music and Art. My brother saw kids walking around with musical instruments and art portfolios. He phoned home to tell me “I know where in this world you belong.” When I came of age, I was enrolled at M&A.

EH: It’s funny how these incidents stick out in our minds. I still remember my sixth grade art teacher accusing me of lying about authoring a poem that I also illustrated. And yet the rest of that year is mostly a blur.

Tell us about the instructors you had who made a profound impact on you and your work. Can you distill for us any of the major lessons you took away from each of them?

EE: Three instructors made a profound impact on me and my work. From Daniel Greene I learned about color, and the application of pastel. His devotion to craft and his drive to educate himself is inspirational. For example, I recall him telling the students that in his early years of study, he went to the museums to analyze the color in the works he held in esteem. He developed an understanding of the flesh color used by, say, English painters as opposed to Spanish painters. He was also very generous with his support and immediately went out of his way to encourage and help me. At The Art Students League of New York, I took a class in anatomy with Michael Burban. His encyclopedic understanding and his graceful blackboard drawings transformed the seemingly dizzying structure of both human and animal anatomy into clear and solid organization. His sense of humor rendered the information slightly less intimidating and energized me into taking notes with great enthusiasm and diligence. Finally, Harvey Dinnerstein’s impact on me is particularly powerful, and cannot be overstated. I venerate the intensely personal and penetrating intuitive heart of his work, which examines in depth human relationships in his world, both intimate and public. The specific yet economical, essential, powerful, and elegant shapes are intensified by his stunning color. As a teacher, his consistently pinpoint comments persist in helping me today as I work alone in my studio. He could not have been more supportive, respectful, and generous with me, and that continues until this day. He is seminal in my development as an artist, and his influence is everlasting.

EH: In your advice in response to a student inquiry in your book, you talk about the importance of solitude in developing one’s individual voice. Was there any particular period in your life and oeuvre where you felt you were transitioning from student work to the more mature and individualized work of a practicing artist? If so, can you talk about that shift and how it came about?

EE: Yes. In fact, I wrote an essay about the experience for Linea, The Journal of the Art Students League of New York, shortly after I concluded my formal study there, and just prior to joining the faculty. Because I wrote that essay when the experience was so fresh, and a passage from it directly addresses your question, may I excerpt it here for you? I titled the essay Composing a Life:

“….My years at the League were rewarding beyond what I could have anticipated. I selected my teachers purposefully. As artists, the breadth of their knowledge, the quality of their questions, their achievements, and dedication to their personal visions are exquisite examples of integrity. As teachers, they imparted their wisdom with unequivocal support.

“The students’ communal pursuit of formal principles in the studio and lecture hall was invigorating. In time, I gained an understanding of the light in the studio and the pace of the morning class hours. The work I was doing felt wholly genuine to my perceptions. I was riveted by the single figure in light, in air, so perfect, and the work poured out in jubilant response. I felt complete.

“I had every reason to stay. Which is why I began to consider leaving.

“Was my work adapting to conditions that were becoming too familiar? Was the great support of the classroom, apparently strengthening, actually undermining my responsibility to question and see for myself? And was I possibly overlooking relationships and incidents in my own life that, because of their nuanced and complex places in my heart, require more acuity than I was bringing to the professional model? I knew that there was more technical development to aspire towards, but I had faith that growth would come naturally in the search for ways to touch upon my most personal themes….”

“And what were my themes? What mattered to me? The luminous spaces of the classroom stimulated an urge to explore composition outside the studio. But what did this mean in terms of the portrait and figure? Is narrative a concern for me? Where does portraiture leave off, where does narrative begin? How do ideas and observation work together? It was exciting to think about exploring a more complex depth of space than I had done, but my overriding love has always been straightforward portraiture. What was my interest in composition about and where would it lead me?

“No matter when I would leave class the problems of arranging and financing a life of figure and portrait painting would be huge. Would my friends and family have time to sit for me?

“There would be times I would want a professional model. I live a distance from the models I have loved to paint at the League and I have not seen much figure painting activity in my community. Would I find access to models to whom I respond and then could I afford to hire them? Will I find obstacles stimulating? Will I persevere? Am I strong? How and if I could work it out I did not know. I would miss my teacher terribly. I loved working in his classroom. I loved his observations. I did not want to lose my time with him. Most intricately, this feeling was intensified by the concurrent and worsening illnesses of my parents: our bodies are here and then we are gone. The urgent undercurrent of painting the human being. However painful, it was time for me to face letting go if I was to be truly present.

“In the same way that I never wish to cosmeticize what I see in my model, I needed to look into my own character. And the exploration seemed to call for quiet, meditative work in solitude….”[3]

EH: There is a wonderful balance, a melding of the personal and the pictorial, which I admire in your work. You seem to care deeply about the character and inner life of the individual you are depicting without ever lapsing into the sentimental or facile emotionalism. At the same time, your work seems so much to be about form, color, and composition, all the while without the sense of impersonal detachment found in the work of many formalists. This is apparent when reading what you have to say about your portraits…you give anecdotes and observations about the character and his or her life while emphasizing the need to be fully present, to preserve the freshness of the encounter.

Is preserving the freshness of this experience ever a struggle for you? Also, how do you choose your models?

EE: There were two – no, three- instances that I can recall where the freshness was absent from the start. The first two instances occurred when I was a student. In the first, we had two models set up together. One of the models appeared wholly uninterested in being there, and the other set herself in a perpetual smile. Trying to paint someone who doesn’t want to be there, for me, sets up an internal battlefield. I recall feeling that I was going in circles, in knots, rather than diving in and submerging myself in my subject. She really was not offering herself, so I could not enter. The barrier was too great for me to overcome. The smiling model conveyed performance. Perhaps the two were opposing sides of a coin: one didn’t care about pleasing and the other wanted to please so much that she assumed a forced facial posture. Feeling struggle-weary and shut out, I abandoned the portrait and did a studio interior instead. The moment of wresting myself from a dead situation and focusing on my new delightful subject was a liberating and thrilling experience. The second instance also involved a model who did not wish to be there. The third occurred very shortly after I had left school and was hiring models. A particular model had been recommended by a local artist who very thoughtfully gave me the names of several models whom he respected. When she came to my studio for an initial meeting, I knew right away that this was not going to work out. I was so new to interacting with models, and I could not bring myself to tell her that the spark was not there for me. So I hired her and spent a small fortune and considerable time working on her portrait. Not that I needed confirmation that the personal response is at the core of any work of conviction, but the experience did confirm just that. So, in all three instances, the freshness was not there from the start. I find that when my personal response is genuine and positive, the freshness is as strong at the conclusion as it is from the start, if not more so, as insights deepen over time. And I believe this has much to do with working from life: the life within the model, the shifting light highlighting different aspects of the form and color. Your follow-up question—how do I choose my models—is perfectly placed, as the answer follows logically from the bored/performance/no spark situations. There are several considerations when asking someone to sit for me. Implicit in my request is that I have a deeply felt respect for the person. I love to paint people who convey integrity, curiosity, intelligence, and, usually, a quiet sensitivity. I feel excited by other people’s devotion to a particular pursuit of work. In other words, that inner life that you referred to in your observation. I have not generally been attracted to flamboyance in dress or manner, but there are exceptions. I tend to pay attention to a modest presentation. I love an expressive body language, be it a beautiful posture or a kind of combination of strength and fragility. And my eye likes pronounced facial features.

EH: In the section of your book which deals with self-portraiture, you mention that “Paintings have to feel totally genuine. They are not about a reasoned logic. The conscious mind has to step aside and allow the deepest connections to be truly felt.”[4] Right before this quote, you spend some time describing the psychological meaning of Self-Portrait in Blue. Is this meaning something you think about prior to and in the act of composing a painting, or is it more of an analysis after the fact? At what point in the process of conception to fulfillment do you push aside your conscious mind?

EE: The self-portraits and all the portraits begin intuitively. The analysis comes as I live with the painting and observe its development. Something feels genuine, something does not, and I make my next steps accordingly. I observe consciously the painting’s construction and my conscience and gut testify whether the construction represents my truest feelings. Throughout the development of the imagery, I find the conscious and the intuitive have equally important roles. One may step forward as the other recedes, and then they change places again. In the end, if the painting intuitively feels non-genuine, it is. But it is definitely not always a straight arrow from beginning to completion. At times, I have started with what I think is a complete idea, only to discover that the first thoughts are only part of a concept that has yet to fully reveal itself. It works the other way around, too. One could begin with a complex idea, and find that there is a more concise way of saying what one wishes to say, or that the core and most meaningful part of the idea is distilled more powerfully in a simple statement. I do revere simplicity.

EH: Oftentimes, I am more interested in what a painter leaves out than what she includes in the image. Can you tell us a little about the role that the editing of visual information plays in your work?

EE: The role of editing visual information. Well, that is partly answered by my thoughts on your previous question. Also, I work in natural light, and I feel as though I am always seeking to paint the exquisite light. On a formal level, for me, editing has to do with being very sensitive to the way in which light reveals and cloaks form. And every detail has to work in concert to create a harmonious oneness, and that means activity here, quiet there, comparative qualities of the edges. I love becoming aware of the overall abstract underpinnings of my subject, and articulating details so as to not encumber or violate the large, graceful rhythms and arcs. On a different front, I have not at this point in time painted complex multi-figure or outwardly dramatic paintings. Though I paint mostly single figure compositions with a kind of restraint, I am always picking up on, there’s that term “inner life” again, and hope to successfully communicate that life within the constraint of quiet. I think that has something to do with editing. Perhaps it is like writing a piece of music, made of words and melody. The words—the “things” represented in the painting—are the story; the music—the way in which the artist creates the harmony—is the heart, the love, the way the artist feels about the subject.

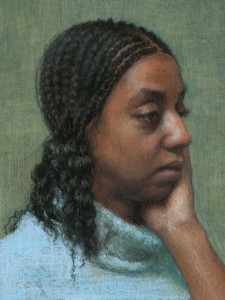

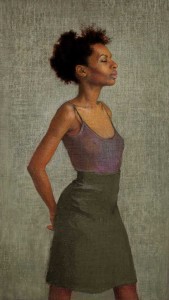

Young Woman with Braided Hair, 6 1/8 x 4 5/8 in pastel on pumice board, courtesy of the Forum Gallery

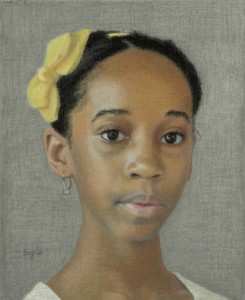

Portrait of the Young Artist Marela Alvarez, 11 1/4 x 9 1/4 in. pastel on pumice board, courtesy of the Forum Gallery

EH: What do you focus on in your paintings now that you didn’t emphasize as much five or ten years ago? What are the most recent directions you’ve been exploring?

EE: I have begun doing some still life paintings and cityscapes in very recent years, and have done some landscape drawings in Italy and China. I want to turn my attention to more cityscape and landscape. My interest lies in the arrangement of large abstract shapes., and aerial perspective. It may require a whole different way of applying pastel, and may also summon an entirely new medium. There has been a major shift this past year: I lost my mother last year, and she was to have been my next portrait. I was faced with blankness, as who would I paint now “instead of” my mother? There is no “instead of my mother”. There is only my mother. I teach at the Art Students League of New York on Saturdays, when there is also a class for children. The children are not permitted to walk through the hallways alone, so they go as a class to the cafeteria at break time. I made the mistake of trying to enter the cafeteria when “hordes” of children were leaving through the same door. They almost ran me over, but one magnificent, elegant, self-possessed little girl held the door open for me. She immediately entranced me, and I immediately wanted to paint her portrait. Long story short, I have now done two portraits of her. I felt my mother’s maternal tenderness “channeling” through me as I spent time with Marela, ten years old, and painted her portrait. Marela’s mother takes her to class at the League every Saturday; my mother took me to the League’s children’s class when I was ten. My mother’s and father’s love is very much a part of the portraits. They would love Marela. Except for having painted four children within one family portrait, which I did on commission, Marela is the first child whose portrait I have painted. I have become quite interested in doing children now that I have lost both parents. This is an unanticipated outcome of the profound loss, and yet another gift from my extraordinary parents. I also have the beginnings of a new painting, which is in the earliest stages of a graphite sketch. The concept of the painting is very personal, and requires corporeal imagery I have not explored before. So, I’ll see.

Ellen Eagle received a BFA with Distinction in Drawing from the then California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. Her pastel portraits have been exhibited widely in venues such as the National Academy Museum, Butler Institute of American Art, Frye Art Museum, Long Beach Museum of Art, Baker Museum, Arkansas Art Center, and Forum Gallery which represents her work. In 2011-12, she exhibited twenty portraits in a traveling two-person exhibit in China. Her co-exhibitor was the curator, whose intent was to largely introduce the Chinese art community to pastel. The exhibit opened at the Dongguan Museum of Fine Art. Eagle teaches the only class devoted exclusively to pastel at The Art Students League of New York. Her writings and paintings have been published in many magazines and books, and her own book, Pastel Painting Atelier, was published by Watson-Guptill, NY, in 2013.

Upcoming workshops:

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Philadelphia, Pa; June 6-10, 2016 email: mkowbuz@pafa.edu

Aria Workshops, Istria, Croatia; June 18 – July 2, 2016 http://workshops.pastelnews.com/registration-form/

Dates TBA – Chicago area; and Art Students League of New York.

[1] John Berger, The Shape of a Pocket (New York: Vintage Books, 2003), 68

[2] Ellen Eagle, Pastel Painting Atelier: Essential Practices in Techniques, Practices and Materials (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2013), 12

[3] Ellen Eagle, “Composing a Life,” Linea: The Journal of the Art Students League of New York, v.9, no. 12 (Fall/Winter 2005), 12.

[4] Eagle, Pastel Painting Atelier, 66.

Leave a Reply