Interview by Jeffrey Carr

The artist Frank Galuszka lives and paints in a magical place, Santa Cruz, California. I first knew him when he was a very well-known and important member of the Philadelphia art community, back in the 1980s when there was a lot going on with the galleries, museums and art schools in Philadelphia. Before his recent retirement, he had been a Professor of Art at the University of California in Santa Cruz. He is known as a painter of mysterious and evocative figure paintings, animated with enigmatic women, and for his beautiful abstract paintings. He’s also an amazing painter of the Santa Cruz beach and landscape.

Frank Galuszka studied at Syracuse University and at Tyler School of Art of Temple University, with an MFA in 1972. For many years he was a Professor of Art at the University of California at Santa Cruz. Previously, he has taught at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia; Vermont College of Norwich University, Montpelier; and The Studio School of Painting and Sculpture, New York. He has had thirty solo exhibitions since 1970 and over sixty group exhibitions, nationally and internationally, including at: the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; the Pennsylvania Academy, Philadelphia; The National Academy of Design, New York; The Drawing Center, New York; and The National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC; as well as in Italy, England, China, and Japan. Galuszka served on the Philadelphia Art Commission from 1988 through 1992 as the chairperson of the Art and Architecture Committee and as chair of the Public Art Council of the City of Philadelphia. From 1994 to 1999 he was the president of the American Society for Cybernetics.

Jeffrey Carr: Frank, I first met you back in the 1980’s, when you were a major presence in the Philadelphia art scene. Then you moved out to Santa Cruz, California, to be a professor at the University of California. You painted a series of magical landscapes of your favorite beach in Santa Cruz, which you showed in Philadelphia. But you are also well known for your elaborately constructed figure paintings and allegories, and for your mysterious abstractions. You’ve retired now from active teaching, and just recently had a show in Santa Cruz at the R. Blitzer gallery of your large-scale figure paintings. I love Santa Cruz, because I attended the university there a long, long time ago. I’m sure it’s changed. What’s it like there now?

Frank Galuszka: The weather is perfect, as it always has been. It’s in a big state of change, not only because of people coming out of the pandemic but because of the impact of what is happening with housing. People from Silicon Valley are moving to live here, and the cost of living forcing out a lot of the hippie-type people who were once here. Still artists and writers here. Big homeless population. Surfers. Academics. Fires. Tourists. There’s a big transition going on. Who knows where it’s going? It’s a very expensive place to live, even though it looks congenially ramshackle the way it did whenever you saw it last.

JC: You were a professor at UC Santa Cruz, and for a while, the department chair. Have you completely retired from teaching?

Frank Galuszka: I’m teaching classes now. I’m teaching a class by Zoom. I had retired, but I’ve got so many paintings, and such a big storage bill, that I have to teach in order to pay my storage bill. That’s the truth. I’ve got a surprisingly large amount of paintings. Five of my students are in China taking the class from China, one of them from a hospital room, where he’s been assigned since he was tested positive for COVID. He doesn’t have any symptoms. And he doesn’t have any art supplies, so he’s doing everything on his iPad.

JC: I’m friends here with an artist who is an extraordinarily good portrait painter. He does these little quick sketches on his iPad, and he’s really good at it. He’s very comfortable with digital media.

Frank Galuszka: I’ve had a number of students do it, and some of them create interesting things with a program that has various brushes. One is called Bad Brush, so you can paint electronically with something that duplicates a brush that hasn’t been cleaned enough, that has got bristles sticking out, or with something like a more bristly brush, or a more stable-like brush. one of the great things about this program is that it gives the people more courage to experiment because they can always go back and eliminate the last decision they made.

JC: I’m impressed with the visual effects. A lot of contemporary painters seem to be affected by the effects you can get with a computer. I was in a collector’s house the other day, and I saw a Lisa Yuskavage print. I liked all the insane Disney Technicolor color that she uses; all these weird pinks, chartreuse, and the color combinations that come out of people working with electronic colors and not working so much with actual visual appearances.

Frank Galuszka: It has a kind of luminosity that’s different from paint. And it’s different from stained glass windows. It’s its own thing.

JC: I like the way things look on the computer screen. As you said, it has a kind of luminosity. With a digital image, I can see details of paintings that I couldn’t see when I was in the museum.

Frank Galuszka: There’s an important aspect to this. Unlike a photograph, I don’t think a painting has a fixed visual identity; it looks different in different light situations, and it also looks different when it’s processed through different media like photography. It’s all part of its identity. For instance, a digital photographer documenting people’s artwork, is able to photograph everything in extreme detail so that some of the people complain that the photographs of their paintings are too accurate. The photographs capture so much detail. It’s different from the way paintings might look with the human eye looking at them.

JC: That makes me think of certain portrait photographers like Avedon, who would photograph people so that they appeared too gritty, with every little freckle and every wrinkle standing out.

Frank Galuszka: With photographs, part of it is using the strobe and polarizing filters. A polarizing filter can make an oil painting look like a gouache painting because it eliminates a certain amount of ambient light that gets reflected back. The strobe eats through the top layer of the paint so that the bottom layers of the paint are more dominant, and the top layer is gone.

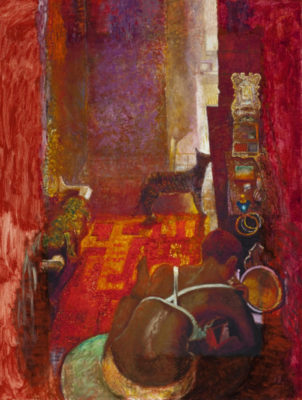

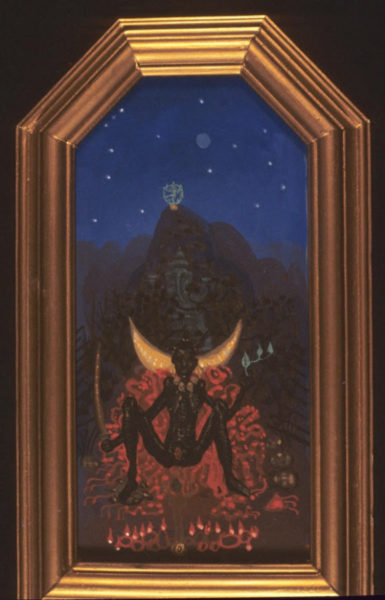

JC: You are talking about the very different ways paintings look in different contexts. Your series of paintings of encounters between the two dueling shaktis, your goddesses, could have a series of votive candles in front of them and be in a little niche like you might see in a Hindu temple.

Frank Galuszka: I would like that. Yes. Candles flicker and change. That would be good. I like daylight too. I think of the Rothkos where he was insistent that they be seen under natural light. Looking at one’s own paintings in daylight, they can look very different from moment to moment. The light changes. That’s good. But not glaring light. That makes the painting so much of an object it undermines space and atmosphere. It’s like the strobe again. There’s this story about Edwin Dickinson when he was doing a painting of the spiral staircases, the ruins of Daphne, that hangs at the Metropolitan. He’d been working on it for years and they took it outdoors to move it, and his heart crashed when he saw what it looked like in daylight. You get used to looking at a painting in a certain kind of light.. When I was in Philadelphia, I would paint my paintings under artificial light. That’s where I had them. And then I would take them into Chuck More’s gallery and he would light them a whole lot. I would complain, you’re over-lighting these paintings! Could you please not light them so much? You’re making them look like a Mercedes in a dealership showroom. And he said, that’s how I want them to look; I want them to look expensive like that!

JC: Talk about Chuck More and his gallery. The eighties were an amazing time in the history of Philadelphia painting, and Chuck More’s gallery was at the center of it. To me, Chuck More was like the Philadelphia Duveen. And I know you are writing a book about this period of Philadelphia painting. (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1951/09/29/the-days-of-duveen)

Frank Galuszka: I love him! And Chuck was actually a fan of Duveen, and he studied Duveen and Duveen’s methods; like the scheme that Duveen had going with the Gainsboroughs, right? He got all of that. (https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/gainsborough-showstopper-the-blue-boy-comes-home-to-the-uk-after-100-years)

JC: What about Philadelphia in those days? I mean back in the 80s and that period. You showed a lot, and you were part of that scene. It was an amazing time.

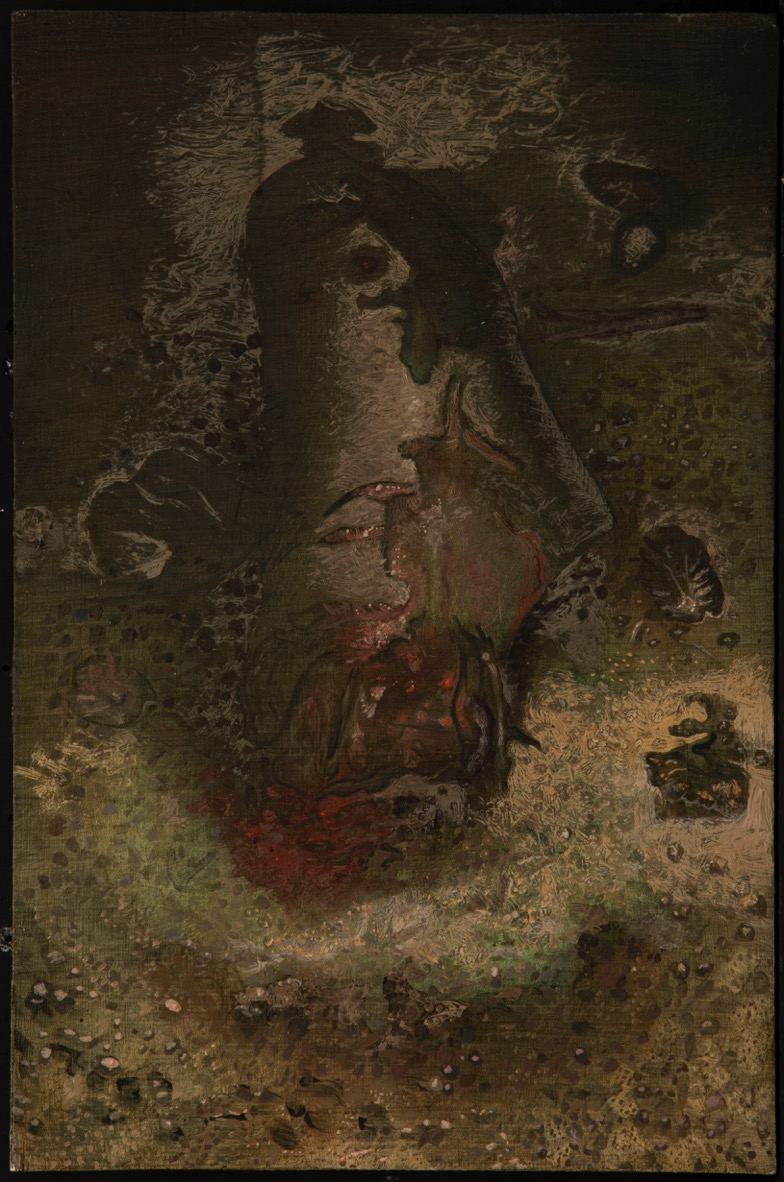

Frank Galuszka: I think it was. And I think that Chuck was responsible for a lot of what happened then, He was willing to show things nobody else was willing to show. He had a certain vision. It included an appreciation of ambiguous, moody, depressive art that no one else was interested in showing. He would show Sidney Goodman paintings and some of my things and things by other people that did not look upbeat and cheerful. There was a real taste for that in Philadelphia, that I think he discovered through doing this. I think even some of Randy Exon’s early paintings were like that. And Bo Bartlett’s early paintings were like that.

JC: I’m also thinking of Ben Kamihira. Kamihira represents this depressive, dark, morbid, and weirdly sexual quality. This weirdness. There was this bright, cheerful side of Philadelphia painting that was the color sensibility represented by Arthur B. Carles, which was a contrast to the dark, tonalist depressive sensibility. I don’t associate your work at all with that depressive stuff, though. Your work to me is mystical and transcendent. There’s a quality of that in a lot of Philadelphia painting; some sort of otherworldliness, a little touch of something that is not quite surrealism, but maybe a little tiny dash of Duchamp. Duchamp’s darkness hovering over Philadelphia. And David Lynch is also part of the darkness.

Frank Galuszka: Yeah, I think that’s right. I think there is that and other things. One of them is going back to the mystical statement. It’s the mysteriousness of tantric art, where some of it has a sublime abstraction and luminous color, and some of it is dark and terrifying. David Lynch’s appreciation of the darkness of Philadelphia is an important factor. He was at the Pennsylvania Academy. He writes and talks about how living in Philadelphia was dangerous. It is. When I was working in Philadelphia, I was living in a place where there were gunshots all the time. My car was shot. My office was shot.

JC: He had a show a few years ago at the Pennsylvania Academy (PAFA) of his early paintings he did as a student. When he saw how much the neighborhood around City Hall had changed, he said that everything was so light and nice, and that he missed the gunshots and the sordidness.

Frank Galuszka: Where I lived there was fantastic. The only negative was that it was dangerous. I had a talk about my work. Here, in Santa Cruz. There were some writers there, and one of them was a mystery writer and he said, “These paintings have a kind of film noir quality.” And then we talked about that a little bit and he said, “It’s like Philadelphia paintings have a film noir quality.” There’s a sense that what’s happening underneath is different from what’s on the surface. This goes back to David Lynch. And also the idea that there’s also some kind of spiritual strangeness going on… like Harry’s Occult Shop. Did you ever go to Harry’s Occult Shop on South Street? You would have so much fun. Dragon’s blood, stuff like that.

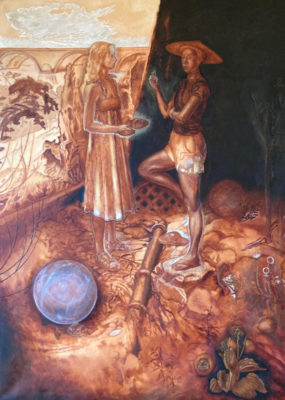

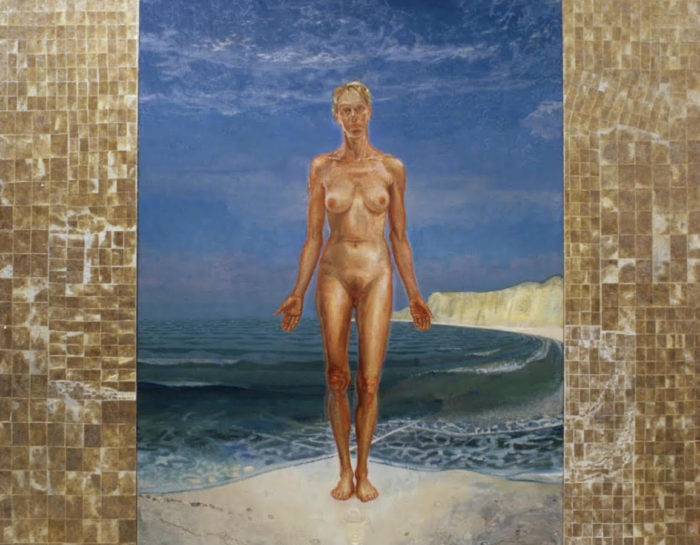

JC: Your work has that quality of spiritual strangeness. Like David Lynch, your work explores a strange, mysterious sort of narrative. I’m thinking of that series of encounters between two mysterious women in which there is some kind of ongoing dialogue; the talking is continuing. In these paintings, I feel like I’ve stumbled into a grove, and there are two luminous emanations, and I don’t know whether they’re visions, or goddesses or actual people, or a combination of all three. These figures are very intense as if they are having a conversation that’s been going on forever. With the two figures confronting one another, you’ve got one light one, who’s luminous. And then you’ve got one dark one, who’s sinister. And she’s the Sphinx. That painting reminds me of that amazing Ingres painting with the interrogation of the Sphinx by the hero Oedipus. She’s very dangerous-looking; a real dark goddess vision.

Frank Galuszka: I hadn’t even thought about the Ingres painting. Even more so, for me, is the Gustave Moreau version of it. The thing about the Moreau, I don’t know if it’s so much in the Ingres, is the way that the earth drops off right at the bottom of the painting, as it does in some of the Leonardos such as in The Virgin and Saint Anne. It not only drops away, but it creates this gulf between the viewer and the painting, so that you’re looking at the painting over an abyss, which I think is something worthwhile. That the cliff or the side of the earth is falling away, also reinforces the picture plane. It creates a sense that the painting is somehow like a cliff itself. It’s a really interesting thing to me.

JC: I love the Salome painting by Gustave Moreau, with the great death goddess holding the head.

I can contrast this to an artist like Bellini, where there is more of a sense of solid ground to believe in, and I’m approaching the figures and they’re in the middle distance. In your own paintings, and those of Leonardo da Vinci and Gustave Moreau, it seems like we are looking into a dark crystal and the objects are hovering there in mid-air, and we don’t know where we are. I don’t know if I’m approaching some kind of visionary state or if I’m actually there.

Frank Galuszka: We could talk about Leonardo for a long time. I’m very interested in the two versions of the Virgin of the Rocks, and what happened between the first one and the second one. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgin_of_the_Rocks). There is the idea that the first one is an apex of a Renaissance vision, but the second one is a full-on mannerist vision, with the quality of imagination and invention taking over more and more completely from observation. That’s crudely stated; it’s just such an unbelievably elegant thing. This goes to Gustave Moreau. I really love the art movement of Symbolism. I’m meaning symbolism in the terms of the Symbolist movement rather than in terms of using symbols. One of the Leonardo paintings is in Paris and one of them’s in London. The one in Paris is the earlier one. The one in London colder, more linear. The earlier one has a red color in part of it, but there’s no red in the second one. It’s austere and artificial. Blue; green, dark. It has a different kind of luminosity. It is almost the same as the other, in composition, location, size, but it has the feeling of a different world. (https://eclecticlight.co/2020/03/27/gustave-moreau-and-symbolism-salome/)

My partner Christina is a big Mahler and Wagner fan. We were watching this fantastic performance of Tristan and Isolde yesterday. It’s all about creating the same kind of space or place, where then the narrative enters into it. But the narrative is just something that is animated within the space, which is mystical, and gives life to the mystical environment that it’s in. I would say that I aim at that kind of condition for painting, too.

JC: I can’t find specific meanings when I look at your paintings. I can’t find specific labels to put on what is being depicted. I can’t find a specific story.Frank Galuszka: Yes, the story floats there, but it’s not about the story. The story is a conveyance of something else. What we’re going back to is the mystical world. There’s just a whole lot of things. And one of them is, for me, the last page of On the Road, the Kerouac novel. The whole thing unwinds. It goes on and on and on, and then there’s no real plot. It’s like a travel book, basically. But then at the end, there’s just this incredible poetic vision that just fills up the entire space of America.

“So in America when the sun goes down, and I sit on the old broken-down river pier, watching the long, long skies over New Jersey, and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, and all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa, I know by now, the children must be crying in the land where they let children cry and tonight the stars’ll be out. And don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.”

That is one of those things, as far as I can see. Especially things like “the evening star must be shedding her sparkler dims. It’s beyond anything. We were talking about David Lynch, and Christina and I had just been watching the 2017 Twin Peaks iteration, and we went back to watch Fire Walk with Me, which I think was an interesting artistic mistake. It takes the great mysterious space in which the Twin Peaks myth takes place, and makes it into a concrete causal chain based on Laura Palmer’s life. It becomes too material, and it loses its power in a strange way. The narrative overtakes the atmosphere, freezes it, dulls it. I have to say that the story itself is exquisitely and intricately plotted. But you could feel the strength and authenticity of the plot without knowing everything. You feel it inside yourself. But then it’s taken away. It no longer belongs to you. It reverts to the author. I think there’s always this temptation for the artist to explain. The author wants to reclaim his creation after it has begun to belong to the viewer. It’s a mistake to explain too much, not only because the artist doesn’t know everything, but because the artwork has already succeeded.

I paint those two figures to find out why I’m painting those two figures. And I never find out. There are more questions.. I keep going back to it. It’s something that is probably going to be with me forever. That’s fine with me. They become the means by which other things become known or visible or come into existence and then go away. There’s a Dali quote that I liked from his manifesto, the Conquest of the Irrational that he wrote in 1935. He’s only 31 when he writes this. It says that just because he doesn’t know the meaning of his paintings when he’s painting them doesn’t mean that they have no meaning. Because he doesn’t know the meaning of the paintings he’s painting when he’s painting them, the meaning is coming through. Going back to surrealism, it is beyond the comprehension of the person at the moment of encountering these meanings as they appear in the work.

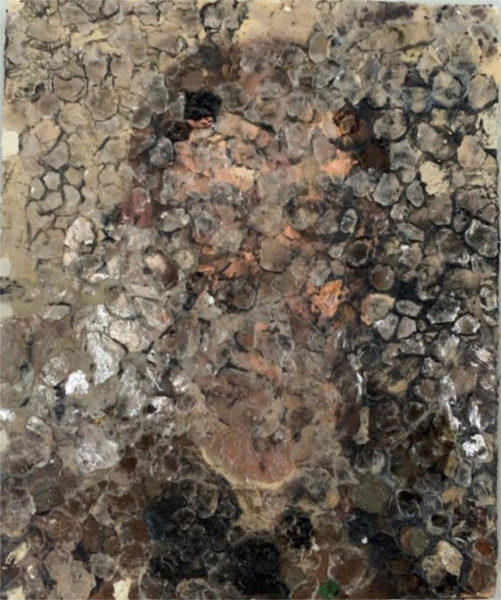

Making the painting is active. It’s not like having some idea and then filling it in. I have no process. When I begin painting, I don’t know where it’s going to go. I certainly don’t even really know how to begin. It isn’t like I have a drawing process that leads to an underpainting process that leads to a blah blah process, and so on. It’s completely open when it starts. And it opens up further. And then at a certain point it begins to close, and then it may open up again. It closes again.

JC: I’ve read that some artists ask critics or poets to come up with titles to the paintings, because they don’t know what they mean. An artist can be so influenced by critics that they start painting what the critic tells them the paintings are about. Artists can start believing in their own myth. After a while, they can start illustrating themselves.

Frank Galuszka: I think that success is damaging in exactly that way, because it creates such expectations, and even expectations within the artist, which narrows the artist’s vision. I think the moment that the inspiration goes away, Pollock paints a Pollock, rather than painting into the unknown as he was when he was doing his greatest work. When de Kooning is painting into the unknown, he’s discovering something like an encyclopedia of ways of creating space in one painting. But if De Kooning just paints a de Kooning, then that creates a negative impact on his earlier work and the earlier work has something taken away from it by that.

JC: People like to explain what they think paintings are about. Like Hopper, for example. Everybody thinks they know what Hoppers are about. They talk about loneliness or the American Scene or something like that. They aren’t about that. A great Hopper is beyond comprehension; it’s inexplicable.

Frank Galuszka: I think part of it is because in his work, there is some uncertainty. He is not affirming the way he painted it in the past, and that this is his way. He hasn’t created a formula. He hasn’t over-branded himself. I’ve done abstract paintings; I do all kinds of paintings. But I think that too often artists create a brand.

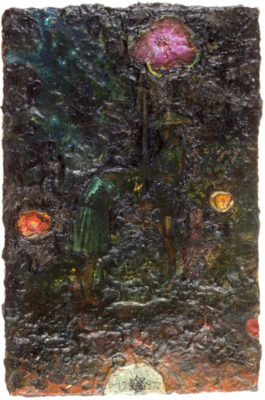

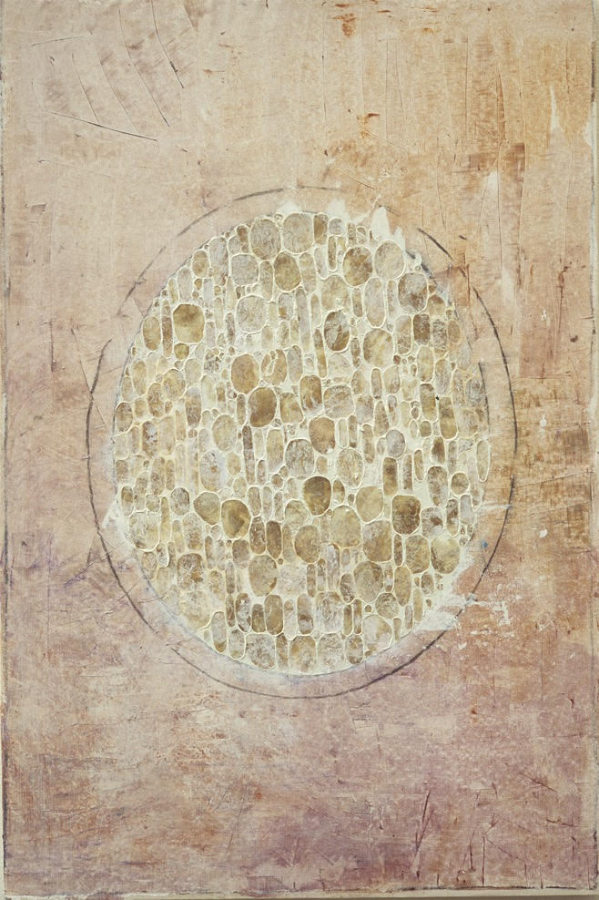

JC: I’m thinking about your very mysterious mica paintings, your abstract paintings, and they remind me of Gustav Klimt. In both, the work has this gold, the glitter, the goddess, and this overall quality of mystery and the unknowable. What would you say about someone who might look at your mica paintings and say they look like Gustav Klimt. What’s the difference?

Frank Galuszka: I like Gustav Klimt. When I first started using mica, it wasn’t to do abstract paintings. I started using it on representational paintings. I did this because I didn’t like the surface of my paintings to be in contact with the same world that they were being viewed from. I wanted there to be some barrier between the surface of the painting and the space. I saw a retrospective of Francis Bacon paintings in the 1980s, and in the large late paintings, he would throw a large splat of white paint on a lot of them so that there would be this thick area of white paint. Then he would frame them in massive gold frames, with glass over the paintings. Of all people, it would seem that Francis Bacon would be someone who wouldn’t want to isolate the painting behind glass, as if that might reduce its expressive power. But doing that seemed to intensify them, to create this privileged or enchanted space between the glass, the underside of the glass, and the actual surface of the painting. The viewer could look at the painting, but they would be physically distanced by the glass. And then they would see through the glass to this space that existed between the underside of the glass and the painting itself. This would create a certain way of seeing the perspective space and also the physicality of the painting, so that they would be combined and preserved by that.

To me, it was like a woman or figure wearing a veil. You can see the face through the veil, but there’s this space of mystery and enchantment between. There is the sacred space, you could say, between the veil itself and the face; an intimate space. It becomes a place where the vastness of space is reduced to an intimate approach toward something, maybe even something that might be beloved. So I wanted to do something like that, and I found the mica in the Wissahicken Creek in Philadelphia, and I started putting that on some paintings. What that created was not only something you can see through, creating that kind of feeling of space, but also the materiality of the mica itself. It created something that seemed right to me, but it’s hard to explain. Looking at some of the Klimt paintings in real life, like the portrait of the woman in gold at the Metropolitan, the paintings look more material in reproduction than they sometimes look in real life. In real life, they tend to be rather thin. When I was a student, Klimt was dismissed as a kind of cheap illustrator. He wasn’t thought of as a serious artist until much later. Now he’s very revered. And I revere him; I think he’s a great painter. But the paintings don’t always come through with the materiality suggested in reproduction.

I believe that a painting has to have a material presence. That doesn’t have to mean it’s necessarily thickly painted. A Vermeer has a material presence, The paint has a vulnerable, tender quality of a handmade thing. It touches the heart to see them.

This is in Mondrian too. Mondrians in reproduction look like they’re cold paintings. But in real life Mondrians have a kind of tenderness to them. They are filled with self-sacrifice that comes from him changing them to make them better and better, and being able to see through the paint at how many times the lines have been moved, and how many times the color shapes, the color squares, the rectangles have been moved. That creates a quality that is hard to explain. When I left Philadelphia and came here, I think that I was more in love with painting than ever, because I couldn’t just see a great painting as easily as I could when I was there. So it created a great feeling for painting to be away from them.

JC: I love your landscapes. For us Californians, the landscape takes us into this incredible light, and your paintings are filled with that kind of mystical energy. You’re like Casper David Friedrich.

Frank Galuszka: I think that’s the thing about Santa Cruz; it keeps moving between being Friedrich and being Bonnard. I love this landscape. I tried to paint the landscape in Philadelphia and failed. I couldn’t really do that at all. Many years ago when I was in Rome, I knew the people who were there at the British Academy. One of them was Graham Nickson, who I still know and am friends with. He’s a great person. There were a couple of other painters, and they were interested in the landscape, and they were all interested in Friedrich. I hadn’t really paid attention to Friedrich; I hardly knew who he was. I thought he was sort of a footnote. So I paid attention to him. Of course, at that time, I was trying to be more modern than that. The idea of using those earthy colors was something that seemed to be a pull into the past that I didn’t want to take part in. But there was a great Friedrich show at the National Gallery in Washington, probably in the very late 70s or early 80s. It was overwhelming, it was so profound, and no denying the importance of Friedrich for me after that.

JC: Friedrich painted rainbows. Have you painted rainbows?

Frank Galuszka: I painted a terrible rainbow. I had a moment in the 60s when I was doing silkscreens. They were pop art things. One of them was a rainbow. It was called “Rainbow Shimmers over Water. Other than that I haven’t painted rainbows. Graham Nickson painted rainbows. Once there was a rainbow that I saw at sunset and because of the color of the light from the sun, the red part of the rainbow was knocked out. It was just the other colors. A blue rainbow. Some kind of weird color effect because of the sun. And I did a little painting of a rainbow that was in the Salinas Valley. It was just a little chunk or like a little square of rainbow; not a whole rainbow. Friedrich painted the rainbow. And that’s a painting of Goethe right? Friedrich has a romantic feeling that is like reading about Goethe in Italy. And there is Goethe’s incredible loyalty to Angelica Kauffmann, who he declared was the greatest painter of the 18th century. They would tour Rome together on Sundays.

JC: Whenever people talk about women artists, they usually talk about their relationships; that she knew so and so, and these are her love affairs and this is her family. By contrast, they discuss men as isolated monuments. Matisse is an example; he is discussed as a modernist revolutionary. But his wife and daughter managed his career as an artist and his daughter was interrogated by the Gestapo. But this is rarely mentioned in a discussion of his career. He is portrayed as this isolated genius in the studio.

Frank Galuszka: They also complained about Matisse doing some radio show during Vichy France. They complained about Matisse being a collaborator. That’s really going a bit far. On the other hand, Dali’s sister was tortured by the communist side in the civil war in Spain. They don’t mention that his sister was tortured when they talk about Dali going back to live in Franco’s Spain. So much is personal. He wanted to go home. He wanted to reconcile with his father. Dali’s politics are complex. Or simple. I don’t know. At one point he was a leftist activist. Mirroring his art, Dali’s politics are retrogressive. In his youth he was a leftist firebrand, he becomes an obsessive capitalist, he dies a monarchist..

JC: We should discuss politics and art. A lot of us, myself included, paint as if politics doesn’t exist. But we’re all affected by politics. What is the artist’s responsibility to political or to larger societal issues?

Frank Galuszka: I want to paint as if politics doesn’t exist. But politics colonizes everything. Avoiding it becomes a political act.

JC: Everybody has political opinions, but as artists, how are we affected by it?

Frank Galuszka: In general, politics is corrupting for art. Politics and art are opposites. Politics is more delusional than art; more narcissistic. I think that the politics of the artist has got to do with freedom, including freedom from the oppression of politics, and it has to do with individuality, intimacy, and direct, unmediated personal relations. This is antipolitical. I think that as an artist you go within yourself to create the thing which is most faithful to things that one feels are true but that no one talks about. From this you can create, rather than creating something which is understood by everyone before you paint it, or even understood by you, or simply very popular. I think that my whole project is influenced by the idea that nobody really knows what it is to be anybody else. Nobody knows what it is to be inside anybody else. I think the presumption of identity politics is that you can limit people, group people together and make them into predictable units or data that you can move around like pawns in your game. This is something that I find offensive. With my students, the whole point of teaching is to emphasize the individuality of the student, as it is reflected in individual style or individual viewpoint, and not that they produce things that are going to be pleasing to me or to anybody else.

I had no particular political orientation when I was young. But through circumstances which I didn’t predict, I went to Romania on a Fulbright when I was 22, during the Ceausescu regime and the Cold War. My political birth was in that environment, in a surveillance culture, an oppressive culture, and in a culture where I encountered the reflection of American foreign policy in the State Department, which was another factor. It was a world in which the whole idea of good guys and bad guys was not what it was about.

JC: I liked what you said about teaching your students to be themselves. If the ideal is freedom and individuality, then perhaps the best contribution an artist can make is to be an individual.

Frank Galuszka: I’m fortunate to teach a class in abstract painting. This means that in the class all subject matter is forbidden. Today’s students frequently feel that they don’t have a right to do something that doesn’t generate some kind of social benefit. This class makes it impossible for them to do that. So then they have to look at themselves rather than trying to think up something which is going to be a kind of contribution elsewhere. If they’re only contributing elsewhere, they’re never looking at themselves. They deny themselves and so lose contact with themselves. In this class they feel so happy! At first, they might resist it a bit, some of them, but then they feel liberated by it. I have a number of Chinese students who have similar experiences. So it’s not just American students. I think it’s a good thing. It isn’t that I’m trying to convert anybody from anything to anything. I’m trying to let them have the opportunity to see themselves as individuals in the course of doing this work.

JC: My understanding is that a lot of the early abstract movements were towards some kind of reductivist, universal visual language that would be divorced from personal experience and convictions. In other words, it had an agenda that you were expected to conform to.

Frank Galuszka: Oh absolutely. Yes, I remember that. It was like that when I was in school. Radical potential is always suppressed. Look at the disappointment of the Russians, who were creating all that stuff (Editor: Russian Constructivism; Suprematism, etc.) around the time of the revolution and then they find out that the government eventually just wanted to have the same bourgeois teacups for everybody. They didn’t want to have anything that looked like a new world.

JC: If I were a Soviet commissar at the time, I would have agreed with that. I would think that people don’t want anything revolutionary or utopian. People want what will make them feel happy; pictures of happy peasants, portraits of fearless leaders.

Frank Galuszka: That’s exactly right. You know the popularity of Kinkade. The popularity of his work says something about a universal desire for coziness, security.

JC: Is popular art always bad art?

Frank Galuszka: Give me an example of popular art.

JC: A tricky one might be Edward Hopper. Is he a “popular artist? Another tricky one might be Andrew Wyeth. Everybody loves Andrew Wyeth. But many of us were taught in art school that Andrew Wyeth was bad, that he was an illustrator. Artists are now reevaluating Wyeth. But as a popular artist, he remains universally beloved.

Frank Galuszka: I love Andrew Wyeth. I also was taught that he was bad. Wyeth threatened the hegemony of modernism. When modernism was about to fall. He created anxiety in the art establishment. Andrew Wyeth is a great original painter. Certain paintings, like the one showing these legs, walking in the fields (Trodden Weed); just looking down at those legs and feet, walking, and the painting of the torn curtain (Wind from the Sea) It’s a vision that he saw and nobody else saw.

Christina and I were in Rome, and we were looking at the Caravaggios from the St. Matthew cycle in the church, San Luigi dei Francesi, and one of them is The Calling of Saint Matthew. And above the Christ, Matthew and the other figures who are sitting down, there’s a wall, and there’s a closed-up window. Christina pointed to that and she said, “Wyeth.” And it’s true. You look at that painting, with that sense of a flat brown light, a kind of plainness and the filled-in window has the feeling of reticence and melancholy that is in Wyeth’s paintings. It is interesting that Antonio Lopez Garcia, who everyone adores, including me, is somebody who admires Wyeth.

In Antonio Lopez Garcia’s paintings of people, and also of things, buildings, anything, he achieves a feeling of dignity and sympathy. This doesn’t seem to be something planned. It is something that comes through his character or personality in the course of painting. Of how he looks at things and paints things,. It is expressed. It comes from inside him. It says something about him. Wyeth’s work also has those qualities. The style is different. It has a thinner feeling or a more brittle feeling.

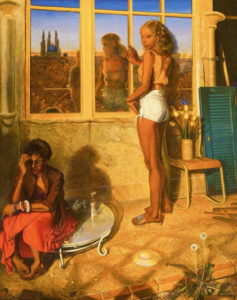

JC: I’m struck by your portraits of Christina. In these paintings, she’s inhabiting her own space, and she’s very much herself. What does it mean to paint a portrait, especially a portrait of someone who means a great deal to you?

Frank Galuszka: I’m glad that you think she is herself in those paintings. I think so too. I’m not trying to interpret her, understand her, or sum her up. There is not that much distance. In the beginning of a relationship, there is an avid desire to close a distance, to arrive at the other in the painting, to consummate the relationship in the painting. It is an objective or ambition that has to do with that emotional moment, but it opens to other things over time, to things that are more subtle, intimate, mysterious and, again, inexplicable. Painting, including portraiture, is not about copying something. It is about these other things.

JC: Many artists just paint themselves. I would have thought that you would have painted yourself all the time. Instead, you paint this Other; over and over again. Your paintings are often about dialogues or interactions between two figures. Maybe that’s part of the content: you want to be in dialogue with somebody.

Frank Galuszka: I think that’s true. I did paint, many years ago, a couple of self-portraits. But I made a decision not to paint any more self-portraits. This led to other things. There was a time when I tried to paint the painting to include the viewer of the painting as a character in the painting. It was a complex effort. I don’t think anyone ever understood it. But I thought that the artist is painting their own portrait, psychologically, in everything that they’re doing. In that sense, there’s a kind of redundancy about doing a self-portrait. Also, the idea of self objectifying is very difficult, so you’ve got this whole problem of objectification and the object. And then, if I’m painting, I’m working from the point of view of a completely subjective environment, and I have no idea what I look like. In fact, the first time I did a portrait of somebody who posed for me, I was painting a schoolmate and I was painting her so intensely that when I stood up for a moment and glimpsed my face in the mirror, I laughed in surprise because I’d forgotten that there was anybody who looked any different than this young woman that I was trying to paint. Her face had become the only face there was. I forgot that there was any other way that a person could look than the way that she looked.

JC: The models for a painting are like characters in a fiction. They’re like characters in a movie. If they’re artists themselves, I think they get into it, and they actually help stage the painting, as a good actor or actress might work with a director.

Frank Galuszka: That’s really true. They become the means by which something comes about. I was talking with a playwright, talking about models. She was asking about models in a painting and I said that some of them are like actors. I have a model that I wish would still work as a model, but she’s also, among other things, a great actress. I said to her, be Mary at the foot of the cross, she instantly fell into a posture, a gesture, an expression- down to the fingertips – just perfect. The artist and model can create between them a separate being, a fictional being. A being that lives its own life. The Mona Lisa is surely neither Leonardo nor his model, but another creature fully believed in.

JC: My experience is that you can’t tell ahead of time if someone’s a good model or not. It’s an intense relationship; even an erotically charged relationship. But it is not about ordinary romantic attachment. It’s about being totally infatuated with the image in the painting.

Frank Galuszka: Intensity of attention is read as erotic. Maybe it defines ‘erotic’. I don’t know. ‘Erotic’ is a supercharged word with a lot of meanings. There is an intensity of attention to the subject and to the painting. With what you are talking about, like the erotic charge, there has to be like an understanding of distance, and distance made visible is felt emotionally as desire. Our friend the painter Scott Noel gives a lot of thought to the concept of desire in painting. I think he defines it very broadly. You should ask him about it. I don’t think about it. I don’t think in those terms. If I have a favorite model, I could look at her so intensely, comparing how she looks with how the painting looks, and the painting looks awkward, distorted, and not like her – until she goes away.

JC: Good models lend themselves to the fantasy of the painting, to the enactment of this fantasy. I’ve found that the most difficult people to draw or to paint were extraordinarily beautiful people.

Frank Galuszka: I would agree. But that’s conventional beauty. As if without personality, where there’s no bias to work with. There is also uncanny beauty that refuses interpretation. It embarrasses creativity. It’s hard enough without bringing beauty into the picture.

JC: Matisse said he was completely dependent upon his models. The artist is inspired by the presence of this fantasy Other; this mysterious other being. The dialogue between the artist and the model becomes the painting.

Frank Galuszka: There is no psychological analysis of this that benefits the artist. It just–there’s really no understanding of it…

Hi Jeff, Really enjoyed this interview. Always enjoyed seeing Frank’s work at Chuck More’s gallery back in the day. His is an interesting, eclectic body of work but distinctively his.

Wow, one of the best interviews with an artist I’ve ever read! I’m posting it on FB and Twitter.

Dear Frank, That’s a great interview. I heard your voice.

Frank

Great to see the span of your paintings, many of them so much alive and part of my memory. They have the power to awaken. To hear of painting, making paintings, teaching painting discussed so candidly is so gratifying. Thank you

FRank

WE have your 4×4 painting of the Isle in the middle of Budapest, inn blue, hanging on our big duplex wall in the middle of downtown Princeton. It anchors what we call the Great Wall of Being because it’s hung like the paintings in the old Barnes Museum. It breathes relevance to all the other paintings around it. Thank you