by Larry Groff

Ann Gale, Portrait with Orange Scarf, 14 x 11” oil on linen wrapped Masonite, 2014

image courtesy of the artist

I am honored that Ann Gale agreed to this telephone interview and thank her greatly for being so generous with her time and attention with sharing thoughts about her art and process.

Ann Gale is a leading American figurative painter living in Seattle. Her portraits were shown alongside other leading painters of the figure such as Lucian Freud, Nathan Oliveira and Alex Kanevsky in the 2011 exhibition “HEADS” curated by Peter Selz at her San Francisco Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

The JSS in Civita, (Civita Castellana, Italy) recently announced that Ann Gale will be the 2015 JSS in Civita Master Class Guest-of–Honor. Ms. Gale will be in residence July 13th to August 3th. Here is a link for more information on her workshop in Italy.

In a January 2013 review for Visual Art Source DeWitt Cheng wrote:

“…Gale’s paintings, which require months and even years to complete, are aggregations of thousands of brushstrokes (Cézanne’s colored oil-paint patches and Giacometti’s feathery, tremulous graphite contours come to mind) that alternate, depending on the viewer’s distance, angle of view and degree of focus, between heavily textured natural surfaces (bark, lichen) and sharply observed studies of atmosphere and anatomy. Look very closely, and a myriad of tiny abstractions spring into view, with every square inch graphically charged with energy.”

Another review in Art ltd. magazine by Richard Speer writes:

“…Gale paints the kind of visages and physiognomies you might expect to see beneath Seattle’s heavy gray skies: ashen, Zoloft-ready men and women hunched before muted, putty-colored backgrounds—and yet the artist enlivens her subjects via twinkly, impressionistic brushstrokes that pop and recede with Hofmann-like push/pull. This is Gale’s viewpoint and paradox: a scintillating technique deployed in the service of an enervating sense of desolation.”

…When the painting is finished, the images do not always resemble their subjects in the standard realist sense—which suits the artist just fine. “Likeness doesn’t drive the work at this point; accuracy does,” she explains. “But it’s not accuracy to the model; it’s accuracy to my perception, and that’s a very different thing.”

Her many prestigious accomplishments include a 2007 solo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum as well as the Falk Art Museum at the University of North Carolina in 2009. Gale received a Guggenheim fellowship in 2007 and a Washington Arts Council fellowship in 2006. Gale is currently Full Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Washington, Seattle and is represented by Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco where her solo exhibition in 2012 has a catalog which can be obtained from the gallery website. Ms. Gale is also represented by Prographica Gallery in Seattle and have a January exhibition at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects in NY.

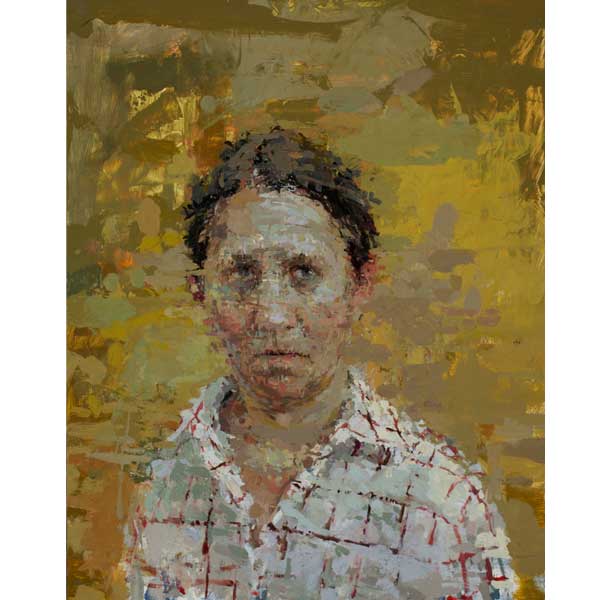

Self Portrait with Red Grid 2012 oil on masonite, 14 x 11 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

Larry Groff: Can you tell us a little about your early years and what influenced you to become a painter? I understand your mother was an artist. What was art school like for you?

Ann Gale: My mother is still painting, in fact I’ll call her today to see if she’s painting. Obviously that was very much an influence and support for me. It still is, it’s nice to have somebody to call me and ask “did you paint today?”

LG: What kind of painting does your mother make?

AG: She does watercolor landscapes. She worked in oils when I was young and I was allowed to draw all the time. If I was drawing I didn’t have to do my chores, which was excellent! I think it still works like that for me a little.

In school, I was fortunate to have art teachers that gave me instruction and time to work in school. They challenged me with different ideas to improve and go beyond what I was doing, even in grade school and middle school. I went to undergraduate school at Rhode Island College and I had great professors Sam Ames, a figurative painter, and Don Smith, an abstract painter. They had a way of teaching me to pay attention to a painting. I found undergraduate school very humbling. I began school thinking that I knew how to draw and soon realized I had a great deal to learn. I was so happy to get into Yale/Norfolk summer program. There, I was exposed to a very diverse group of students and faculty that opened up my idea of what painting could be, what the language was like. I felt kind of untethered. I didn’t know what to do there.

LG: At Norfolk did you ever feel that there was a stigma or less support towards work done from observation or did that not seem to matter?

AG: No. Working from observation wasn’t stigmatized, but I also don’t think it had any authority. It was interesting to see the kinds of leveling of everything.

Graduate school was kind of similar, only bigger, more intense. William Bailey, Andrew Forge and Bernie Chaet were at Yale then. We talked more about painting than figuration. It really gave me a vocabulary for that discussion in my own studio practice – considering what I valued in the painting, not just in the picture. Andrew Forge once asked us to define our assumptions in painting. This is something I continue to think about.

LG: I’ve heard the critiques at Yale could often be very pointed, even brutal sometimes. Did you find that experience?

AG: Yes, I sometimes felt vulnerable and exposed. Often the critiques were difficult because they were saying something I was trying not to say to myself.

Portrait in Last Light, 2012 Oil on copper 12 x 9 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

LG: What have been some of your most important influences that shaped how you paint today?

AG: I am very curious and sometimes obsessive about observation. It is very intense to just be close to somebody and to be looking at their face and down at their lap and being aware of their gravity and proximity. I have been influenced by painters who reveal the intense experience of observation in their work. One of the artists that I found and studied when I was an undergraduate, was Antonio Lopez Garcia. We went down to New York for his show.

LG: That was his earlier show in NYC in 1986 at his Marlborough Fine Art gallery.

AG: Right, I remember standing next to my teacher and him slapping me on the back, saying “breathe, you’re not breathing!” I had seen paintings that were accurate like photo-realism or work that was powerful, like Italian Baroque painting, but I hadn’t felt this before. I couldn’t forget it and it was intriguing that painting could do that. That it could pull me into it’s world. It had a very human sensation to it. I always wondered what is it that isn’t just information—he seems to have transcended that. I remember when that big catalog came out. I ordered it and sat on my doorstep every day waiting for the mailman, waiting for it to arrive.

LG: That’s an amazing book, The Rizzoli Catalog, it’s probably my favorite and most used artbook. Did you get to see his big show at the Boston MFA?

AG: No, I didn’t get to see the show in Boston. That was horrible to miss that show.

As an undergraduate my teachers showed me Edwin Dickinson’s work, which I found incredibly mysterious and intimate. I also found a little black and white catalog that included British figurative paintings. These painters weren’t as well known at the time, William Coldstream, Lucian Freud, Patrick George, Uglow, Kossoff… I was interested in how the process of perception was present in the work. It was almost like they were mapping their sensation. It reminded me of Giacometti. I became obsessed over that little group of paintings. And then when I was at Norfolk we went to visit the British Museum and I was taken by the back of the collar by one of the teachers and made to sit in front of Kossoff and the Auerbach – saying I should not leave until I sat there. I had seen these pieces in reproduction but it was important to see the touch and the way they seemingly transform, revealing the fleshiness of the paint. That doesn’t reproduce very well, that feeling that I really like about painting. To understand some things about a painting I needed to sit in front of it for some time. So those groups of representational paintings especially, really interested me in school and since.

LG: Is your painting dependent on the model being in front of you in the exact same position? How critical is working directly from life in your work in terms of trying to the sitter’s exact likeness, proportions, skin-tones and such?

AG: I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. I think it has been changing in my work, how I think about it. I’m used to the tradition of working with the model, where I mark the model and the model tries to sit still in the same place. My studio used to look like a dance studio because I marked my feet where I was standing. It looked like these little shoe-prints everywhere. If I moved a couple of feet closer I would re-mark how everything would change relative to where I was standing. Recently I’ve had a couple of paintings and drawings where the model changed and I followed the change in my painting. I usually have the model in 3 hour sessions and about 2 hours into the session, the model looks different, they give up to gravity, they’re thinking about something else now. My attention seems clearer. There is something more honest in it. So I found myself following that adjustment a lot in my work. Even my own place, I would move in or out and that would change things in the painting. In a technical way, it can make a big muddy mess but it can keep it open. I had to reexamine these same proportions repeatedly. It wasn’t just measuring precision but the idea of re-measuring and re-finding something has become more interesting to me now. Also many of these paintings, the larger ones especially, have gone on for a very long time and sometimes people change. They have gotten ill or they’ve gotten well, their life circumstances have changed. It’s not something I want to ignore; it’s something I want to watch. It’s more truthful; things are constantly changing. When I’m willing to give up what I have, what I see in the painting feels more conscious, more alive.

LG: I remember once reading a quote from Edwin Dickinson, I think, that I something like “a painter should always be paying the model and not the other way around.”

AG: That is probably very good advice.

LG: I’m curious to hear more about your measuring and searching. Would you say measuring helps to free up the painting process; that searching for truth through measuring helps turn off the inclination to paint preconceived notions and helps to keep the painting open?

AG: Yes, The search becomes part of the subject of the painting. The figure is so familiar, it is challenging to see past prejudged ideals of the body and face. Measuring can provide an objective lens for perception.

LG: I find that so fascinating because it seems so counterintuitive that the more you search for accurate mark or tone could be more liberating than with loose, bravura-style brush work. That the actual observation and exactitude doesn’t have to be constraining, like with painters like Euan Uglow with his obsessive measuring, with all his little position marks on the wall.

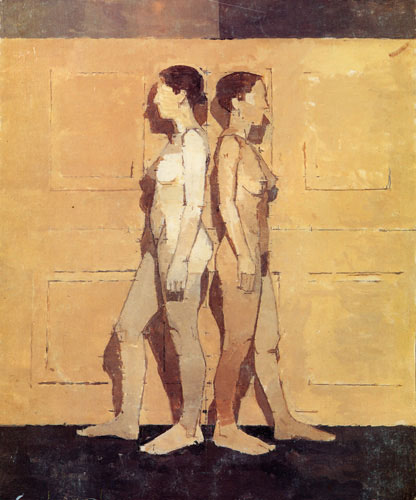

Euan Uglow, Tension, 1992-3 22 1/4 x 18 5/8 inches

private collection

AG: I was able to see a less finished piece by Uglow a long time ago. It was of back-to-back women, it wasn’t a large painting. It looked like a little study with a very limited palette. I like how he was using that limitation to really ask a precise question about relative measuring.

LG: Your work seems different though, as if the measurement is on a whole other level. It’s not just about measuring; it goes beyond that in a way. Would you say that is true?

AG: There are different kinds of measuring. I have a broad definition of measuring. You used the term that it could be liberating. I think it is, it’s incredibly liberating if I let it take me somewhere. I think I was really struggling with color within figure/ground relationships. I then changed the way I was observing and measuring color. Instead of trying to achieve some correctness about the background or the part of the body, I tried to be accurate the light and how the color could find the light. I had to keep standing back and asking, “is that the color relationship or not?”—so it’s half-measuring and half-feeling because light is very much a sensation, much harder to measure in an objective way.

Robert with Gray Shirt 2012 Oil on masonite 14 x 11 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

INTERVIEW CONTINUES

Rachel with White Robe 2011, oil on masonite, 14 x 11 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

LG: Is there a point where the painting takes on a life of it’s own? Do you respond as much to what you are seeing in the painting as much as seeing on the model?

AG: I try to spend more time with the painting than with the model. Though I’m not always responding, actually putting paint on. Recently I’ve been drawing a lot from my painting. Sometimes I have to turn them to wall and not look at them for a while because I have them memorized, I can’t see them objectively anymore. I have a huge six foot by six foot rolling mirror in my studio and I can look at things through that and that’s helpful but then I just know it too well. But after I’m away from it for a time, I’ll go back and draw from it before the model comes.

LG: While looking at the painting, or the memory of the painting?

AG: Though I occasionally draw from memory, usually I am looking at the painting. I try to draw what I really see. Trying to objectively understand what’s going on in the painting, treating the painting like it’s the subject of the drawing, just drawing it, what I see—not what I may want it to be.

Lately, I’ve also been doing this after the model leaves. I have maybe a 20-minute ride from home and back. I try to use that time to digest what I’m thinking about in my painting. So at the end of the painting day I’ve been writing a little notes, because it feels like things are clearer just as the model is leaving, of what to pay attention to when I come back.

LG: You never really work on the painting when the model isn’t there in front of you?

AG: I do but it is more often editing or refining relationships, than putting things in. I might wipe areas out or scrape things together so that I have to deal with them again.

Self Portrait with Blue Stripes, 2008 Oil on Masonite 14 x 11 Inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

LG: Do you scrape things down frequently and then build up or is your process more additive? Or is it half and half—additive and subtractive?

AG: It’s both. If I’m only adding paint everything gets very flat so I try to think about there being an inside where I can push a mark into the space of the painting. I admire the palpable sense of atmosphere in Edwin Dickenson’s paintings as he scraped and blurred spots of color with his little finger. Lately I feel like I want to pick marks up and slide other marks underneath but I haven’t figured out how yet. I often have to rebuild spatial intersections.

LG: I haven’t seen your paintings in real life only these higher resolution images give us a glimpse of what your surfaces must be like. I imagine there is a lot going into the building of those surfaces, with taking off and putting on and all kinds of fantastic maneuvers to make those surfaces.

AG: The surfaces are produced from the accumulation of measurements. Pushing areas together pulling apart, scraping and rebuilding. Some areas get dense but I don’t usually let them get too thick because that can hide some optical relationships.

Babs with Ribbons, 2005 Oil on masonite 14 x 11″

collection of the National Academy of Art and Design NY.

LG: How do you approach measuring when painting? Is the underlying grid important or do you prefer to do it all more by sight or feel? Do your marks result from measurement or relating forms to an underlying structure or grid? Some of the marks seem to have little to do with a grid and are more turbulent while others seem meditative. Is this something you can talk to us about?

AG: Some of it is very much about the grid, so I was happy to hear that word in your question. It’s always there in the rectangle, very present in my observation. I think it helps to measure against it. To see a gesture compared to a vertical is much more sensitive.

So I’ll follow a lot of those, like plum-lines and horizontals, through the picture to try to see the gesture of the figure, from the knees up through the body to the top of the head. I can get a long measurement with some of the grid lines and I do that a lot in my drawings too. Actually, it’s easier in drawings because I can pull that skinny little line through anything. I’m trying to learn that in my paintings.

Other things are not so much a grid but a linear movement where I’ll follow something that is like a ribbon through space. I think it’s the direction my eye is taking. I might go from the floor, over someone’s lap and into the background. I think of it as kind of a path through the painting and through the figure. I’ll repeat that several times, sometimes I’ll cover an area of the painting so that I can travel through the painting and avoid filling in, or getting stuck on some nameable object, a chair or a head.

As I’m observing, I’m trying not to follow the things with names, I’m trying to follow my way between them and through them. So I’m thinking of either that grid that hangs through everything or these other paths that are available that move through the figure and space.

LG: Why do you fragment the form and not paint it in continuous tones or broader tones? Are you trying to paint the atmosphere around the head as much as the head itself?

AG: The fragmentation is the residue of repeatedly measuring with pieces of color. Sometimes when I look at a piece of color in space, near the figure on the wall, sometimes it almost feels like that color is almost pushing on the figure and sometimes it feels that it’s sliding behind it. I know where the wall is but I’m trying to look at what’s that little moment of color doing. I try to mark each piece of color relative to one or two other pieces of color. I’ll often find three pieces of color, forming a triangle in space that goes in and out of the figure. I’ll revisit and readjust them. This accumulates into the atmosphere of the painting.

LG: So with the shapes of your mark-making, you mentioned you might find a triangular shape of color that goes in and out of the figure. How do you determine those shapes? Is it more of an intuitive thing? What are your thoughts about your mark-making and what determines their shape or quality?

AG: What determines what I pay attention to?

LG: Some of your marks seem very slow, careful and meditative and others seem more turbulent, gestural and less on a grid. So I’m curious how you determine the shape of these marks.

AG: I think I know what you mean. Some things I observe, I have to slow down and be very calculated and the mark would then do the same thing. I’ll add little, short marks will that are trying to tighten up some little calculation or comparison. Things like the gesture, trying to get the weight or the movement through space or any kind of bigger gestural comparison is more accurate if I’m doing it faster. Like a 30 second gesture drawing can sometimes be more accurate in terms of gesture than spending an hour on it.

LG: Right, that’s a good way of saying it.

AG: It’s necessary in my painting to make those big gestural movements.

LG: I love how you control the form openness, closing and opening the edges in and out with the background, we really can breathe the air in your paintings. I’m curious to hear about your edges. Do you manipulate edges with the knife or mix color on the canvas or do you mainly just mix on the palette and leave the brush stroke alone once applied?

AG: I mix my paint on the palette. I’ll put the color down and try to see if it looks different on the palette than it looks in the context of the painting. (I might ask myself) Is that right or does it need to be a little more intense or a little darker compared to some other color? I’ll mix a new version of the color on my palette. I don’t blend in the painting. But some of the marks get bent or pushed in because I’m measuring space. I have to let go of one thing to do another, sometimes I have to say to hell with the color for a little while because I need to consider how measure and manipulate the space. To do that I might need to manipulate the thickness of the mark or the clarity of the mark or edge.

LG: Is there anything that tends to give you the most trouble in a painting?

AG: I think getting something significant overall when I stand back. I don’t know what I would call it. Sometimes all the little parts that I’m working on any painting will be there, but then there’s a bigger more elusive relationship…

LG: Like with a color relationship?

AG: Certainly, sometimes I can get the little neighborhoods of color to work however the big ones will be difficult. Especially on a large painting I have a lot of little marks and so I struggle with standing back a lot I wish I had an eight foot brush I could paint with because I can’t see the whole painting while I’m painting. But it’s also the representation, does it feel like something is in there, is there a consciousness, an intensity of moment inside the painting. That’s not just something I can put in. I have to keep paying attention to the whole and remember to question that. That’s why I’ll often do a lot of little drawings of the painting. Something has to work on a larger scale in the painting and that’s difficult.

LG: In an earlier interview you said: “I started to look at people in terms of their color environment and the presence had to do a lot with not just the local color of themselves but what color they seemed in a certain situation”. Does this play a role in getting unity in your paintings? What might you share with regard to unity and harmony in painting?

AG: I started to think about the phenomena of color when I had this wonderful model with a pale yellow skin. And it seemed like she had almost a purple shadow going down her torso but when I tried to paint it, it wasn’t purple at all even though it seemed purple. I had to get everything in the painting to have kind of golden hue. I could then see that the purple was really just a bit less gold color than the other colors. This was a great learning experience. I may easily name what an individual color is but the phenomena of the color, what the color feels like, requires a sensitivity to the larger context.

LG: So you build the whole painting around making the sensation of that color happen?

AG: Often that will be a key, a measurement that I will keep going back to and so it’s a way of unifying the painting. And a way of getting one presence that goes through the whole painting. In a sense, the gesture of color.

Cézanne is reported to have said:

“Art which does not have emotion as its principle is not an art…Emotion is the principle, the beginning and the end, the craft, the objective, the execution is in the middle.”

LG: Would you say that painting from life is as much about optics as the experience of being in a place and connecting with the thing you are painting?

AG: I admire work that is about optics and work that is more concerned with emotion. But with me, in terms of optics, there is kind of emotional or psychological connection that I am pursuing.

LG: Right, some painters may worry about risking sentimentality, that emotionalism might detract from the formal concerns and prefer a detachment in their work. Your paintings seem to have a good balance between the formal and the humanistic. Your work seems to go beyond the optical experience. Can you speak about that?

AG: I think being precise with the formal language brings specificity and weight to the subject, emotional or whatever the subject may be. Though we can speak about these concepts separately, in a painting I think of them together. During the adjustment of the figure, the space and the light itself becomes an emotional character. While there is a precision to the measuring, there is also an intimacy that is revealed and equally crucial to the process. Though the figures are abstracted through this process, they are not neutralized as subjects.

LG: Can you tell us something about the role your relationship with the sitter plays? Are these people you know? Would you say you are also trying to evoke an emotional presence in the paint? Do you start the painting with this thought in mind or does the painting have to evolve on it’s own terms?

AG: It starts in different ways. It can start with a memory. I’ve painted some models for many years and have spent a lot of time with them and so now have specific memories of them and I will do the painting to deal with that memory. Sometimes it refers more to another person that they remind me of, or an older memory of someone else. But often it transforms into something else because of the immediacy of what I’m actually looking at. And so it becomes this conversation between what I’ve started with and what I’m observing in the moment.

Often it has to do with the light. As the quality of light changes through the year, it transforms the emotional character of the painting. I struggle with how to continue. Lately I’ve been very interested in taking that leap and following the observation wherever it’s going. If I can be open to that, it might give me a fresh eye, like “I haven’t seen this before, or I haven’t noticed this feeling about this person before.” So the painting will show me something that I’m lucky to see and I’ll grab onto that. The emotional character of the people is a tangle of things they remind me of and how they’re changing in front of me.

LG: Would you say these things that remind you of something causes you to transcend the specifics of that sitter to something more universal or beyond that person?

AG: Usually it’s something more intimate, something may remind me of the way my father sat, one of those emotional characters in my life. That memory helps me pay attention to the sitter more acutely.

Peter Turning, 2013 Oil on linen on covered masonite 14 x 11 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

LG: What do you think about figurative painting today? Who are some people that excite you most and why?

AG: My studio is filled with a lot of catalogs and books and cards on the wall. It doesn’t seem to matter if it is new. I also don’t just look at figurative painters, I really admire Jake Berthot’s paintings and drawings, as well as Stuart Shils paintings, Alex Kanevsky – Alex has a space that feels like a strange dream or memory, Sangram Majumdar has such beautiful color, color as subject, he understands color. I think some sculptors are interesting, especially the way they draw, like Rachael Whiteread. Her drawings are really sensitive and beautiful and Marlene Dumas is making some very powerful paintings.

LG: You will be teaching this summer in Italy at the JSS summer program in Civita where many students will be painting outdoor landscapes – any thoughts on how teaching painting the figure will differ from the landscape? Or do you think that is even an issue?

AG: It’s mostly perceptual painting. So with just those two words there is plenty to talk about. What is it you think you are seeing and how are you building the painting. I love looking at landscape painting. I often look at landscape paintings for a sense of the whole. I feel there can be a sense of whole, like an epiphany, I feel like I can understand the whole thing in a landscape.

I’m looking forward to discussing landscape paintings because it’s something I look at a lot. We will have many common things such as light, space, mark and paint. I’m really looking forward to seeing the light in Italy again. I haven’t painted over there in awhile. The last time it shook up my palette, making me realize I had a lot of color habits that I didn’t even know I had. Painting in such a different climate, it really taught me a lot.

LG: I imagine painting indoors and outdoors would be a significant difference too in terms of your palette.

AG: That’s a hard thing to learn too, to be efficient and have studio or painting habits that will work. Actually right before we talked I was meeting with a graduate student who I just sent out in the rain to paint. You have to figure out a way to do it. I admire that about landscape painters, they figure out a way. Deciding what they really need to bring with them and how to get it done. There is something great about alla prima painting too. It makes you decide on your priorities, what do you really need to resolve before you walk away. It’s good to be faced with those questions.

LG: Do you plan on painting landscape yourself? Are you bringing your painting supplies?

AG: I hope so, I’m not sure what the set up is yet. All I know is that it can be hot.

LG: Sometimes it can be, but if you get up early and find shade it’s not bad.

AG: I will probably bring some supplies and I will be traveling after the program’s over with my family. I’m sure I will at least do some drawing and studies.

LG: The JSS has so many terrific excursions to see all the great museums, churches and places. My favorite is the Morandi Museum in Bologna, just fabulous.

AG: Just that would be worth the trip.

Self Portrait with Headband, 2007 Oil on linen on masonite 14 x 11 inches

image courtesy of Dolby Chadwick and the artist

LG: What qualities do you think a great painting teacher should have?

AG: I’ve learned the hard way that I can’t really tell my students a lot or force them to understand. I’ve learned to take my time. I’m a better teacher when I’m asking them a pertinent question, one that gets them to look at the painting for the answer. Even in a beginning class I’m a better teacher when I’m getting them to be their own critic. I’m giving them the questions to ask of their work, so they can better critique their paintings. So they can make decisions that aren’t just for technical reasons, something bigger than that. Sometimes it’s hard to take that time, when I’m in a hurry I’m tempted to give them the easier answer and show them a way to fix something but I don’t think that’s being a good teacher. I have to take my time and ask questions that will make them really consider their paintings.

LG: When is your next show? Where can we see your work?

AG: My first show at the Steve Harvey this coming January. I’m very excited about my first show with Steve Harvey, I’m crossing my fingers. I admire the painters he shows. The following year I have a show at the Dolby Chadwick in San Francisco.

Wonderful work and a terrific interview.

This is an insightful interview, a dialogue of unusual precision regarding an artists process and intent. It is a practice so thoroughly based on observation of both the subject and the dynamics of individual colors on canvas which is even a more unusual skill. One of the most provocative comments refers to subtle differences of the light and the model’s temperament occurring during a painting session and the challenge in seeing (grasping) this phenomenon. What, in fact, to do about this, dare I ask?

Surely there is no limit to the depth a painter can go into consciousness and yet the process of doing so is a step by step, journeyman, clay feet labor.

hello!I am a Chinese, I am a fine arts graduate student, is studying A you can Gale, I hope can get a little bit of her information, can you help me? Thank you very much

Thank you

I loved this interview and love the work, too.

Thank you for another great interview Larry.

Your questions were such that they allowed Ann to succinctly reveal her mental, technical and creative process. This is a very thought provoking and inspiring interview as so many of them are.

And it goes without saying, the works are phenomenal!

ANN GALE S work is stunning!

good interview,

thank you!

I’ve been a fan since seeing your work in Chicago about fifteen or sixteen years ago, Matrix Gallery? Navy Pier? I can’t remember. Anyway, your work has remained burned into my brain since that first encounter. You are a wonderful painter Ms. Gale. It is a treat to hear your answers to Larry’s questions.

Thanks for another good interview Larry.

Noel

What a great interview! there seem remarkable parts like Andrew Forge’s question about presuppositions occurring at the beginning, but most strongly the discussion of meanings and places of measuring and the candor about process and studio mentation. Thank you Ann, I love your work and look forward to your show @ Steve Harvey. And thank you Larry for your resonant questions.

Ann Gale will be speaking at The New York Studio School (8 West 8th Street) at 6:30 PM on Tuesday, February 10, 2015. While seating is limited, this lecture is free and open to the public.

I just saw Ann Gale’s perfect show at Steven Harvey. It’s a small gallery, but the work is immense, in the sense that it’s truly profound, and technically consummate. She doesn’t “transcend” the specificity of her models, she plumbs their depths. After the death of Lucien Freud, she is one of the finest painters around (not just representational, but painters in general). I want to rush back to the gallery to look at these paintings and drawings again!

Thank you Larry … A wonderfully insightful read.

I can not stop looking at her paintings!!!