Stuart Shils End of a Sumer Day, Last Blast of Warm Light, Looking Back, 30×42 inches

click here for a larger view

Stuart Shils in Conversation With Nikolai Fox

March 2012, in advance of an exhibition at steven harvey fine art projects, April 26 – May 27, 2012

Nikolai Fox is a Philadelphia based photographer, painter, musician, and filmmaker. You can find out more about him at his website, http://www.nikolaifox.net/

photos courtesy of nikolai fox, jesse freedman and stuart shils

Nikolai Fox: So last time we were talking, we were discussing a kind of a struggle related to pulling away from previous ideas you had about making a painting and the idea that there’s no way you can escape the kind of life that you’ve lived to this point in front of previous paintings and your involvement with the history of painting.

Stuart Shils Yes, well you can never really escape from anything, you just learn and re learn how to carry who you are and what you have, and translate that into what you want to be. You go to school and learn how to do this and that and you see what others have done and you go to art school and learn a way of doing things and go out into the world expecting or looking for some kind of “success”, whatever that means, and you construct a world based on intellectual understanding and in time you explain to yourself who you are.

And then, one day something happens and you realize that the explanation of who you are really doesn’t work anymore because you had an experience or saw or felt something or had a complex layering of experiences and you admit to yourself that something might have to change. And if you are going to be honest with yourself, the way you proceed can be very difficult because you might have to turn yourself inside out or upside down. But does it mean you have to throw away everything that you were? Of course not, but when we confront the unknown or the prospect of change, the road can be perilous. Also, I like the leaving home analogy, how do we leave home – gracefully with optimism and a dreamy head, with fear, or like first learning to drive a stick shift, with many lurches and stalls?

NF: It seems like there is a work ethic in these paintings, where you’re pushing on everything you’ve ever known and thought about and felt and there’s an incorporation in each piece of all those struggles and an attempt to move forward and keep from being stale.

SS: The path we are trying to make and to stay on is to work and to follow that internal, flickering meter of response, intuitively, and at the same time to be aware of the intellectualized/analytical mind and history; and concurrently, pushing it all away. But where is that other place, how do you get into your gut or whatever part of your body your impulses come from, that you feel with, how do you get access to that? How do you dig your nails and hands into the pay dirt? That place is not in the intellect, it’s something else and you have to go out there as a foot soldier ready for battle and willing to risk desperation. Because you are not going to find the answer by making libations at the altar of your intellect or at the alter of history with a rare 1952 Chateau Lafite. it doesn’t work.

I have to forget all that and follow some…, I don’t even know what to call it, I don’t know what to call that place from which I know the answer comes. It’s a place that I can only sense and I’m connecting there as each painting comes into focus. It’s a place where like you’re biting into an animal not even fully dead and blood is coming out and if you’re honest it can be pretty scary. That pink painting over there, the one on the end of the shelf, I don’t know how I made that. It’s coming from an internal conversation with myself but also it’s coming from being out of doors for many years with the sensory sails hoisted, from the long conversation with many observations and considerations of things in the visible world even if they were only absorbed peripherally. And when you’re working “out there”, your job is not imitating what’s there, you’re trying to bring it all inside of yourself and beat your way into an interior place where it can get cooked up. And how all of this is going to come to the surface, how it’s all going to work out remains to be seen.

All of these paintings are rooted in sensation; like that painting:

Leaving Rome, Early Evening, Late Summer, 30×40 inches

I’m leaving Rome on a bus in the early evening, and I’m sitting next to a very good friend and we’re deep in a conversation mulling over our experiences around the city that afternoon, walking around and going into the Palazzo Massimo, and we’re settled into the bus talking and I get a glimpse of the city as we’re passing out of it, in the last, overheated gasp of light. I didn’t have time to make a drawing, I just saw it out of the corner of my eye in the midst of talking to my friend. I carried that all year until I sat down two months ago and tried to pull some form of it out of my memory.

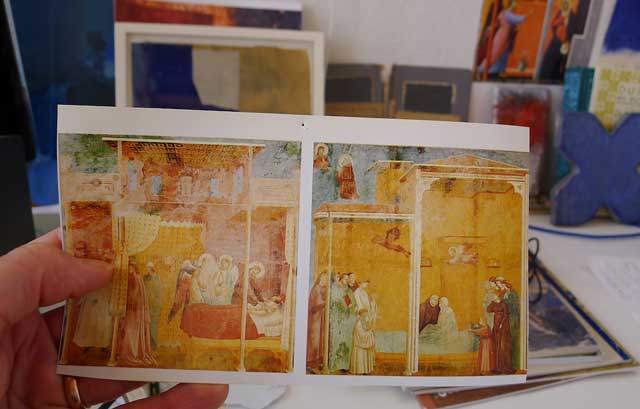

Fresco Walls at Palazzo Massimo

NF: So is it something that was really in the depths of your memory? I’m thinking about the analogy you made a minute ago about how it’s not necessary to push things to the bottom of the ocean. When you said that I immediately thought of the cave paintings and the recent documentary (Cave of Forgotten Dreams) that Herzog did and the kind of physical journey that these modern people have to take to get into this cave to see the paintings. I wonder about the kind of physical journey that the cave artists had to take to get to this place where they would make them. It seems like if they were going into the depths of the cave in order to scribe these images onto the walls that there was some kind of intuitive feeling that it was necessary to bury this expression or to go deep into the earth and place it in the depths. Perhaps they were doing things on the surface also that we don’t have because time has worn them away, we can’t make any assumptions and of course maybe the caves were not so deep as now. And now we have – this week – James Cameron, one of the richest and craziest filmmakers in the world, going 35,000 feet down into the ocean to take pictures because we want to know what is in the pockets of our existence that we cant reach physically. And so in a sense this memory that’s coming back to you that is a glimpse, you’re saying it sat with you for so long and I’m curious, was it buried at times or was it always just screaming at you and finally you let it out.

SS: Well you’ve both posed and answered a deep question. In a way we no longer have to go into that earth cave because (pointing to the head) this is also the cave. Our heads, our memories, our experiences, everything we’ve absorbed and constructed, this is what Freud re opened for us, he was like the Maître De or the Sommelier, he had both the wine list and he brought us in and opened up that interior door, put on the light and got us settled. All painters are not siting outside painting exactly what they see, but neither was Corot. Art is invention, so let’s not think he was making literal inventory lists and anyway, what is literal and how much information does one provide? When I was a student I remember there were the people who worked from “life” and then those who worked from the “imagination”. But in a way, really, what is the difference and what’s the inter relationship?

The thing that I’ve been dangling in front of myself in the last couple of years has been the prospect of understanding how to work in the studio accessing memory and just what is that, what does “memory” mean? So we’re calling this show The Residue of Memory. When I had that sensation while on the bus leaving Rome at the very end of the day with the last gasp of warm light on the city and I was talking with my friend in the middle of a deep conversation. I was not thinking “Oh, this is an art moment.” We have many moments and most of them just sit on the shelf. The thing is, how do we get to them later and then how do we paint them when they are not right before our eyes? How do we get back into those moments?

Often it’s by drawing, like the ones behind your head on the studio wall. Often I’ll return to them, and the same with those collages, I’ll put them up as peripheral but significant reference, as a way of taking myself back to a memory resonance; and it’s fascinating to me what even simple linear movements on a page can offer as far as recall, aide – memoire. None of these paintings are descriptions of specific places, they are evocations of the feeling of place, and drawings help establish ledges of concrete footing that contribute to the improvisational development of the forms in the studio. It’s a very different process than before.

NF: Are you sure about how different the place is? There’s something really interesting about what you just said because I think about the work I know from looking at reproductions and seeing it since I met you 12 years ago. The size, the way they’ve grown in physical size over the years is really interesting. Especially as you make the point that this show is about or called The Residue of Memory, because it defines for me, or suggests, where that place is.

You told me that in the years after you left school the small scale was a really important thing to you. Small size I mean. And now the title of the show is a very clear pinning of the priority of the internal landscape as opposed to going out and looking at things. But the influence of the external landscape is so strong and this is bigger than I’ve seen you work. It’s like an eruption of color and size. Is there anything about that that you have a clear thought about? Like the way that the size of the paintings has gotten bigger? Do you think there’s any connection between the power of memory and the buildup of looking for so long and saying well now I’m going to approach paintings from memory?

SS: Great point. I never really considered the relationship between the power of the memory to the size of the canvas. But now I want them to be even bigger, twice the size of that red one, maybe 40’’ by 70’’. I’m ready because there is something just delicious about not only seeing the color smeared out on this size but there’s something about that size and the use of materials and the physical presence of a brush stroke or a mark that in a way I find liberating in terms of the reality of the paint is taking over, separate from what it is describing. And of course, what is it describing, or what is any painting describing, if not only itself. Each one of these paintings even though it (hopefully) looks very fresh on the surface, underneath is a tormented sequence of many moves, many marks; they’ve gone through so many stages. And along the way I’m getting very worked up, threating them, like I’m going to beat the crap out of them, you know just getting so angry and unleashing a storm of emotion that brings many, many changes. .

Detail of End of a Sumer Day, Last Blast of Warm Light, Looking Back

NF: And if the painting is smaller you can see the edge of the image very clearly. And as the painting gets bigger at a certain point it’s so big that you wont see the edge. If you stand in front of a 20 foot by 20 foot painting and you’re close enough, you’re entire visual experience is inside the painting and when you shut your eyes and see only with our mind’s eye, there’s no edge to the imagery that is generated by our imagination and memory.

SS: Well that’s an important observation and doing these has given me a completely different handle on how to read a painting. I’ve been using the camera on my phone as a viewfinder all year. What the lens does is it pushes the image back, away from us, so we see it differently. The distinctive optical fact of camera is that with a lens you can see whatever you are looking at, all at once. I can’t see a painting all at once with my eyes, it’s physically and optically impossible, unless it’s really small or far away. We talked about this the other day. How when I look at that,

A Giotto in small reproduction

I can see the related pattern of shapes and colors, all at once. But when I look at a painting this size, like the one on the wall, 30 x 40, I can’t see it all at once. I have to look at that part or that part or that part, except, when I hold up my phone and I look at it through the camera because in the camera everything gets pushed back, flattened and can been seen in the lens as a unity – like a flash, it reads as a pattern, like on Google maps and you’re looking down on the earth from above.

NF: Last time I was here we talked about what is important about a diptych as opposed to a “real” painting. You were saying that people in the past were critical of the diptych, they said why not just make one canvas, who does this? But there are important things about the role of the two images as they come together and what that line in the middle does to your head as you look at it.

glorious afternoon with so many surprises, 20×40 inches

SS: I don’t think the line in the middle has to be seen (as some people have stated) as an awkward divider. Because in fact, that line proposes some kind of game, a visual game and in a way is a witness to some things. These are physically two separate canvases but they exist as a single image, together as one, but it also breaks down into two separate parts each with its own contribution. For me what’s interesting is that that vertical line is also a separator and the world on this side is confined within those edges and the world on this side is confined within those edges. Yet curiously they also live together, but when you look at the composition and geometry of this side, it’s a completely different story than the composition and geometry of this side.

NF: I don’t think you necessarily have to explain it with words either, I mean it’s a very difficult thing to explain with words because you obviously wouldn’t be doing it if it didn’t play some kind of important role that you either wanted to struggle against or support.

SS: Right. But I’ve had to explain it in words because people say what is this, who puts two canvases together?

NF: And you can’t just say it’s a diptych?

SS: No you can’t just say it’s a diptych. I had an exhibition of paintings 4 or 5 years ago and in the catalog they edited out the separation between the two canvases, as if that division was some kind of mistake. The thing is it would be nice to just put away all the words but people always say things so you have to explain things back to them.

NF: Well do you? I always feel frustrated when people ask me about visual work that I’ve made, or music. Why would you be trying to address the issues and struggles that the medium of paint presents with words?

SS: I feel with painting that all you can really do is go to the edge of the sea, take your clothes off, jump in and start swimming. You know you can’t stand there and put your toe in, slowly, etc. You just have to swim. I often think, “Why am I wasting my words, like why even bother, they’re not going to understand anyway?” Yet, at the same time you can use words. I mean, you must try to use words with precision to help someone who doesn’t get it, to learn how to be a better reader. I think it’s possible to use words almost as stones in a garden. You put down slates in the garden to get from the front to the back without having to walk on the flowers or vegetables. But at the end of the day painting is not about words at all nor about the verbal intellect, it is much more for the senses. You just have to be aware of the fact that your point in using words is to take someone to the shore and then to let go of their hands and say bye, bye I’ll meet you for a coffee at 2:30, see you. And then they’re on their own. And that’s it!

Years ago just after 9-11 when my Irish paintings had become atmospherically incomprehensible for some people, I knew a collector who couldn’t figure out why I was abandoning where I had solidly stood and the place that he liked in my work, and he said to me something like “especially in times of economic difficulty, we want paintings that reinforce our understanding of the world as we already know it, and I thought, oh my God… I don’t want paintings that reinforce anything except the imperative and fun of exploration. I want art to be like a playground and like a frontier. Where else can you have fun and explore – in the corporate boardroom, at the bank?

NF: Well it’s wanting something to lead you to something new and to give you hope right?

SS: Right, to open up a new place of wonder and that’s the beauty of all kinds of art especially the kinds that we don’t know and is perhaps or can be, difficult. Think of the possibility of getting connected to a new way of seeing, a new way of hearing, a new understanding a kind of art that maybe I didn’t like before that I’ve come to understand. I didn’t always like Agnes Martin or Gorescki, or Guston or Morton Feldman. And not that many years ago I didn’t know the work of Sheila Hicks, James Bishop and even Conrad Marca – Relli. Now, I can’t imagine not knowing that work. We try very hard at opening ourselves up to new experiences and to indulge the senses in different forms than those that are familiar.

NF: It’s the point of the experience.

SS: That’s the point of experience. And that’s what life is all about in a way. Not, making more money or buying another suit and being able to say “Well I have another Armani.” I went with my son Gideon to see that fantastic piece that Richard Serra installed in Gagosian Chelsea, Junction/Cycle, and you go into this gallery space and it was that snake like piece with the tilted walls and once you’re in there for like a minute you don’t know where you are. He’s completely shifted, erased and transformed your understanding of what it’s like to be on this planet.

NF: Well he’s riffing on the labyrinth.

SS: In the most brilliant way. And he’s used these heavy metal walls that feel like they’re made from silk underpants. The material is so beautiful and massive yet seemingly without weight at the same time, and they’re tilted and quite high and he’s taking you through a disorientingly, provocative narrative of movement. And a minute and a half later you don’t know where you are. Where else can this happen except in art? And who cannot go into that installation and not come out screaming with delight? It was the same with the Orange Gates. When Christo opened the Orange Gates, I remember reading a sour, depressing critic in the New York Observer who was saying they were an “unforgiveable defacement” and a desecration. Come on, that installation provided us with one great urban playground experiences, pure exuberance, and asked us to reopen our consideration of the dimensions of possibility within art.

NF: What you said a minute ago about the way you couldn’t imagine using cadmium red and certain things in the past that now are exactly what you need to be doing is really interesting and that relates to what you brought up about Sera and the feeling of the labyrinth and the way you lose yourself and, that something you look for in work is the way that it can take you away from what you expect. And it seems to me that the relationship with painting that you have is one in which you establish a certain parameter that’s just at the edge of understanding and then you head for the edge. The task of art is something that slowly pushes back that veil so that it’s pulling you into places that you don’t understand; but in a way you can enter those places you don’t understand with an understanding of how to be open to it and how to let it be an empowering experience instead of being something that makes you afraid. To me that seems like one of the most basic and important roles of art. It’s a shame when people only look at things that don’t challenge them because it’s important for us to grow and move past the things that we’re afraid of.

I remember seeing a Bonnard show when I was 20 like 1998 at the MOMA, right? I didn’t get it at the time. I liked a couple things, but now, years later I still look through the catalog and I’m totally in awe and I wish I could go back. My father said you have to see this show and I walked around and I looked at everything because I understood that by being engaged in painting and being engaged in art that one of my jobs was to push myself emotionally and psychologically and to look at people who were considered masters even if I didn’t get it. To stand in front of the painting and to look at everything I could look at and let it hit me in as many ways as possible so that maybe it would open me up and take me into these places I was curious about.

SS: I saw that show, it was the one John Elderfield did at MOMA. I had seen another show of Bonnard at the Phillips in the early 80’s, and I went with a school friend of mine who hated it, and I could feel those colors calling to me but I couldn’t find the road in given my academic education, and with the context of his contempt, I hated it also. I couldn’t even begin to comprehend Bonnard when I left school. But then the show at MOMA in 1998 hit me like a ton of bricks, so exquisitely beautiful. I was at a point ’98 where qualities of understanding were starting to open up for me on the Irish coast, my work was changing, and that show just wiped me out. I remember thinking though, “What am I going do with this?” I mean, it was like feeling color for the first time, not understanding color, but feeling it. This is a beautiful thing about a retrospective. Having all that work together. I could feel the radiation from the color coming into my body. And it’s like I wanted to take somebody and kiss them, I was that worked up.

NF: What was the difference do you think in where you were coming from when you saw it the first time when you said you hated it?

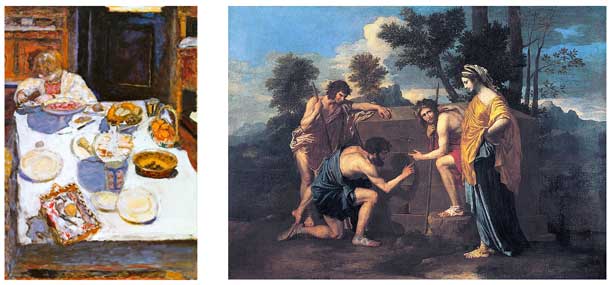

SS: Experience. You know that what a painting can mean to you at one time is not what it’s going to mean to you at another time. This is why we must have ourselves in front of paintings all the time because it takes years. You know with someone like Poussin, I’ve gone through a very long, complicated conversation. Loving him in school, hating him when I left, not looking for 20 years. Now I’m in love with him again but in very different ways. I’m not looking towards Poussin as a model for how to paint and I don’t need him to be something that he isn’t. I really don’t think that those masters and it doesn’t really matter which masters – Poussin, Piero, Matisse, Bonnard – they don’t want us to make paintings that look like theirs in appearance, really. The lines of interest in all of them are much deeper than surface.

And the other thing is that everything you were saying about fear and discovery and the unknown – that if you’re really engaged in painting, you have to submit yourself to the possibility that … well let’s go back even another step, that if you’re really honest with yourself.. and I guess everyone is honest in a different way so I can’t talk about other people, but one of the things I’ve learned from this whole procedure of making these paintings is that… making these really threw me into a different kind of encounter with fear. Because these are larger oil paintings and they’ve been done over a long period of time, many, many days and I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. And the fear factor (as I began working and asking myself what am I doing and trying to find a footing), put my head through some very complicated places. But then I began to really enjoy that and to recognize that this is exactly where I want to be, in this place where I don’t have a footing or concrete sense of security. At that point so much is open in terms of how to illuminate the path ahead of you. You just make it up as you go. Remember, nothing existed before someone brought it into life and that’s our job. To use or judgment, discretion, senses and daring, to make form.

NF: Is it something that you learn to enjoy as it is happening or… It sounds to me like the engagement is so intense that you’re not self aware enough to be able to say “hey this is fun” as you’re doing it, but as you step back, it’s like you’ve just run through an obstacle course and you’re sweating and your body is alive and you feel like you’re worn out and you’re going to sleep well that night.

SS: It is something that invigorates, and when I went to Ireland and started making those paintings it was like painting on roller skates, drunk. I was out of my mind for a long time in terms of that place and the experience in it, completely pulled the rug out from under me. And it has been the same this year with this work. And with regard to how we are in or within experiences, an analogy might be, if you’re out on a date with someone very nice and you’re having drinks and sitting in a quiet corner of a restaurant and kissing them and you’re looking at something else across the room simultaneously, you’re not really there in that moment within the kiss. If you’re looking at something on the other side of the room and saying to yourself oh look at that nice sports jacket, I want to get one of them, then you’re really not there, you’re not in that kiss. And with painting you have to be in the kiss.

NF: Or if you’re thinking about something.

when we were walking near the walls of gaiole, 20×40 inches

SS: So how are you really there with painting? Frank Auerbach refers to those special moments as, “glimpses of glory”. And the reason that many of us work, is to know more deeply, this place in which we are both pulled simultaneously into and out of ourselves through our connection with the material and the whole process. Many of us discovered it very early, that place in which we leave our minds, where we are dragged into another level of consciousness, swimming in this beautiful world of our higher self, where we’ve gone outside of “normal” daily, waking conversation. And it doesn’t last forever. Nothing lasts forever. But we’ve seen glimpses of it and that is what has kept us going. Not the sale of a painting or the fact that we were able to draw the building with proper perspective. If those were the things that keep us going then we’re bankrupt to begin with. Instead it’s those glimpses of that place where it’s like we are in love with something, where there is a kind of an intermeshed unity of feeling and purpose and gesture.

NF: And you can’t realize that you were there until it’s over. And so you have a painting when it’s over if you’ve done it right.

SS: And that’s what we try to do in painting. And where we tear our hair out is when we’re working and then the spell gets broken, because we know, we can sense the wind pushing us back and forth between the inevitability of the process of doing and then standing back for that proverbial, conceptual cigarette break and bringing to bear the analytical mind. But each painting is an attempt to prolong the spell, to throw us back into the hypnotic grip and that only comes through process not through thought. You can’t just come and say “ok, I’m here, it’s spell time.” You have to work and often that means grrr, ***#$$#%F++??%%$%. You work and you scream at yourself and next thing you know, you’re cruising to Mexico with an ice tea and a cigar in your hand and you’re listening to the New Riders and the Purple Sage and you’re just cruising. And then the song goes off. But you know, that’s the place, and you learn how to go back. So you learn how to re enter, you learn how to go back fluidly and rekindle the relationship and it might mean knocking down a few walls and going back into the painting, taking some things away you thought you liked or needed.

NF: This experience of complete connection to the moment and the revelation of existence is the thing that the paintings embody at their best. And that as a gift to the viewer is why people value art.

SS: It’s the whole point. Where you tear your hair out is when people say, “Well modern art stinks.”

Of course you want to share your adventure. That’s why we read national geographic. Because there we can see that Thor Heyerdahl built a raft and… Each one of us is not going to build a raft but we can then go out and we can buy a copy of Kon – Tiki.

NF: Well, Thor wrote Kon – Tiki, but he didn’t have to. He could have just gotten on the raft. But writing the book was not as much of a good time as being on the raft. Think about what it means to write a book. You’re sitting in front of a machine for hours and hours and hours on end struggling, revising, being frustrated, you’re back hurts.

waking late from the previous night, 24×24

SS: But it was the sharing, it was his desire as a human being to share this thing with other people because that was part of his agenda. He saw himself in the world in that way. That’s what drives me crazy about these artificial walls of division that we make based on ideologies. “Well, I don’t look at abstractions because it’s empty and simpleminded”, or “I don’t look at realism because I know it’s for putzes”. Come on, It’s all the same. You can look at one type of thing and also enjoy another. The point is trying to really get into what it is and to check your preconceptions in the coatroom, if you can. And to ask, what does it mean to you? And you don’t need to know history and lineages and chronologies and you don’t necessarily have to have read Gombrich or the Janson History of Art.

NF: Janson’s Histoy is his attempt to share his experience. But it’s a very different kind… It’s like trying to share something that people have shared already. Right? It’s a very strange thing. The historians chore. To try and take this very potent experience that we’re talking about and reframe it in the context of time.

SS: Yeah and of course he’s writing a textbook for college, where time and form are being dissected and evaluated in a certain kind of formalized chronology.

somewhere in germantown, 19×22 inches

NF: According to other events that are considered appropriate by whatever….

SS: : Right. I had a really interesting experience as my first year of art history at college. The class was taught by a painter, her name was Lee Hall. She wrote a famous and very scandalous book about the De Koonings years later and she was an abstract painter whose imagery was rooted in landforms and I couldn’t even comprehend abstract painting at the time. But she said to us the first day, “I’m not going to teach this as chronological art history. I’m just going to show you lots of paintings that I like and I’m going to talk about them.” So she didn’t start with the caves. She made many different kinds of juxtapositions and talked a lot about qualities of seeing. Not about the kind of stuff that my students who are taking art history at the University, you know, they come back and they tell me how these classes are being taught and it all sounds so anti visual.

NF: Memorize the titles and the years…

edge of the city before a storm, 36×36

how did i find my way back from here, 20×32

SS: Yes, but mostly, all those ideas. I don’t want to know about ideas! But visual ideas yes! How does a yellow feel next to a blue? What is an orange shape doing next to a red? But that’s not really an idea, that’s more of a quality or condition. And you made some point earlier about talking about paintings – the point of talking about paintings is to bring you closer to the painting and to the experience of the object, which is a sensory thing. Ideas don’t help. Ideas are for Neo Platonists, for the academy. And I don’t mean the Pennsylvania Academy (PAFA), I mean the intellectual academy. Remember that Plato hated artists and didn’t want them in his Republic, he was very concerned with ideas and regarded the senses with suspicion. Within the theater of art, whether holding the brush or standing in a gallery space, I just don’t see how ideas relate or how anything relates unless they/it take you closer to the process of looking and engaging with the senses. Unless all those words send you with urgency to feel like, “come on, now, quick!” That’s what good art writing should do. And there are writers like that like that, and when you read their work you just want to go and look and taste.

wandering in the sun after palazzo massimo, 36×36

NF: It should illuminate the work not explain it.

SS: Illuminate the work and it should leave you with your tongue hanging out, like it does in a gelato shop. Where you go in to get an ice cream and the colors are so seductive and provocative that you just can’t wait. Our job, whether as a painter or a viewer is really to learn how to feel. To feel in front of a painting. Not to think, but to feel. Of course once you go into analytical mode you have to learn how to ask yourself questions about what it is you’re looking at, but even in an analytical mode those kinds of questions often border on sensation and we have to learn to do both. It’s like when you’re cooking a fish and you test it. The testing is really being done through the senses, not through ideas. We have to learn and relearn this and ask ourselves all kinds of questions. If you want to be analytical you could step back and say to yourself, what’s this painting all about, what are the shapes and what are the colors? But as the maker, basically to just get into it we have to open ourselves up to its form from the senses and let those qualities come inside, to taste them. And learning how to taste is not about words or ideas, yet, it is informed by layers of experience and analysis preceding that moment. And it could be very risky. Because when you’re at your easel in front of a painting, you’re engaged with a form that you cannot make sense of rationally or logically. And potentially you might not initially understand what’s going on or to even see it clearly, so you might have to redefine for yourself the basis of or foundation of your understanding. And I’m saying that as a painter, I mean there is a possibility that making paintings is going to turn you upside down, and are you willing to go there?

Another really great interview with Shils, digging deeper each time, voicing what I can’t, he gives us the encouragement that freedom to pursue this world of art making needs.

Another fantastic conversation with another fantastic artist. Thanks again.

Beautiful and insightful interview, gloriously rich paintings. I love the notion that words can’t often adequately describe the feeling of painting. And why should they?

This is one of the best interviews I have read. It was ironic to be reading words about words not being able to express the visual experience…but these words were extremely rich with ideas. Thank you!

Thank you for sharing this interview with Stuart. It amounts to an inspiring, challenging “sermon.” Very inspiring and encouraging. Thank you, again!

Brilliant discussion by a painter I’ve long admired. However inadequate words can often be, Shils uses them as sensitively and with as much “gusto” as he paints.

Forgot to say how much I liked the paintings and wish I could see them. About words, that can’t do justice to the painting, but are necessary for me to try to stay conscious about direction and what is informing me.

Stuart Shils is a great painter. I first became interested in his paintings when a friend began collecting them. Many of his earlier pictures were painted in Philadelphia neighborhoods where I grew up or was familiar with. Good interview.

great interview. I had to read it a few times and mull it over before commenting. I don’t have much to say other than I think Stuart’s a very intense painter and thinker. This will be a great resource to return to again and again…his passion is contagious. many thanks

Ah what a great read! I’m not at all surprised by this direction, it’s easy to see the progression in Stuart’s work and it’s fantastic. I can’t imagine what he’ll come away from the Sedona workship with…wish I could go but am laid up w a new knee. Thanks for this interview!

This is a marvellous interview, and one I will read again and again. As an artist I can relate to this constant re-examination of who you are – so many ideas of who we are have to be thrown away during the search to bring forth, and understand, one’s own vision.

Wonderful interview, thought provoking,I shall read it several times. so sorry I missed this show!

For years I felt frustrated by the loneliness of the painter and his possibility to share thoughts with others who really understand what painting is about.I feel so lucky to live in this century where technology gives me access to interviews like this one and see works of great painters like Stuart Shils .These are real moments of happiness and sharing .Thank you

Dina

Fascinating and thought-provoking interview. Interesting to reads words about the difficulty of using words as descriptive expressions of art when the ultimate interaction between artist and the art, and between viewer and the art, is ultimately about feeling. I also enjoyed the discussion about risk-taking as an artist and the need to be willing to take your art into new exploratory areas. There is a connecting thread between risk-taking, searching deep for new expressions, and the core essence of art as feeling.