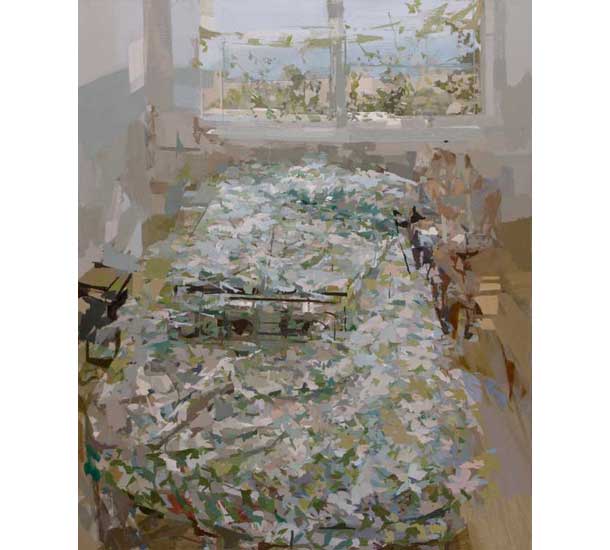

Untitled, 40” x 33”, Oil on linen, 2009-2010

click here for a larger view

Interview by Neil Plotkin

Stephanie Pierce grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, studied and lived in Boston, Massachusetts (The Art Institute of Boston, BFA ’96), lived in Ashville, North Carolina, studied in Seattle, Washington (University of Washington, Seattle, MFA ’06) (and lived in a few other places along the way) and currently lives and teaches in Fayetteville, Arkansas. She has just concluded a solo show at the Alpha Gallery in Boston and was also a part of the Pink Moon show at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects and had an extensive speaking tour this past spring.

Stephanie was generous enough to be interviewed over a two day period and these are some of the highlights of our conversations.

Neil Plotkin: You’ve lived in three corners of America: Boston, Seattle and Arkansas. How have these very different locations impacted your work?

Stephanie Pierce: It’s hard to separate how you develop as a person and artist from your relationship to where you live; they are so layered and dependent on one another. Each time I’ve moved there’s a lag time where it takes me a while to figure out how the place changes what I’m responding to and looking for visually.

When I moved from Memphis to Boston, I wasn’t prepared for the pace, density, and feeling of disconnect I experienced there. I felt pretty alienated, which also had to do with a thousand other things from growing up, and I responded to that new context through urban landscape.

Untitled, 19” x 18”, Oil on linen, 2011

NP: Did you feel alienated because you were from the South and then living on the East Coast or is it just your age?

SP: Everything. The way that I grew up was pretty out of the ordinary. I could have been on a talk show or something. I moved out when I was sixteen and was focused on painting since I was fourteen or fifteen.

I always knew I wanted to be an artist. It was what mattered to me and it was one of the things that pushed me though difficult times. And then in high school, I had this absolutely amazing art teacher who was very intense, really critical and really informed about art, especially modernism. By the time I got out of high school, I was pretty well informed for a high school student.

Culturally I was shocked in Boston- I had to relearn a social language. People’s character, sense of humor, and how they engaged with each other was completely different. I felt used to more immediate conversations with strangers. In Memphis people interacted more, messed with you in a certain way, there’s this fluidity and constant back and forth. In the North, there was more of a social distance.

Untitled, 24” x 21”, Oil on linen, 2010

And sub culturally, I was part of the punk scene, and so moving to Boston; it wasn’t like there was this nucleus that you could just fall into. You really had to seek everything out. People didn’t just pull you into the fold. You had to find your way in.

I think that for me, painting has always pretty much come from perception, and has always been this issue of what to paint, how you access it, and why you paint it. And so, inevitably place has affected that.

In Boston, I felt like oh, there’s so many things in this city that I’m interested in, fleeting moments, glimpses of highways, views that I can see for half a minute on my train ride home. In a broad sense I was probably always looking for something that was sort of existentially sad. I would spend a lot of time walking, miles and miles and miles, just looking for something that hit you in a certain way that made you feel like you could have an emotional response to it in painting.

When I was done with school, I moved to North Carolina after briefly living in Memphis and Chicago. I found it difficult to paint there because I wasn’t interested in painting the beautiful natural world, though I wanted to be in it. It took me years to finally understand that when you change the place, the things you think about visually are going to change, and how to keep up with that.

After living in Seattle and now Arkansas, I began looking within the interior for the subject, it’s been good to simplify the starting point, testing the potential for something of interest in a small corner of a room.

Faldum, 46” x 60”, Oil on linen, 2010-2011

NP: You spoke about how your process needs to be explorative, and you can’t have a map of where your paintings are going. And you said the painting itself dictates what it needs in order to be finished. Can you talk about the creation of one specific painting from start to finish, and how those dictates come about

SP: Well, I don’t know. Faldum and Wolf Interval, both evolved through several different iterations, source remaining the same over the period of four to six months.

In Wolf Interval, I kept going back to it over and over, thinking I wanted to deal with more space or less space. I was having a problem with relationships of scale, the division of the windows to the bed, my viewpoint, and the scale of the image as a painting. I was standing in a place that I wouldn’t normally stand, which was to the side, and trying to figure out how to deal with the space between myself and the plane of the window.

After months and still feeling repelled by the space laid out in the painting, I started moving my position to stand close to the window, and then re-positioning the viewpoint 5 feet back, which forced changing locations in the painting. So I just started thinking that the way that I’m getting unstuck is literal, I’m going to walk forward and backwards and make that a painting. As I worked I wasn’t settled on a time of day, and eventually the clash of many overlapping times of day became what made the most sense for the painting. It ended leaning towards the interval of day into night.

Usually the first two or three weeks might be exciting and feel open. Then it goes through a period where it feels like it can’t ever possibly turn into anything, and how will I ever make that happen? They all have at least five or six major re-openings or something has to happen that is telling me something new for it to stay alive and go somewhere. It’s a continual process of looking, responding, destroying, renewing.

If I’m lucky it will get to a point where I’ll think This is exciting how these things are fighting with each other in this one place, and it’s making all of these different reads of the space and the objects happen all at once.

Wolf Interval, 40” x 60”, Oil on linen, 2010-2011

Untitled, 46” x 60”, Oil on linen, 2010

NP: Do you move the objects a lot while you’re doing this in order to help in that process, or do you just redraw it?

SP: I move myself mostly. My point of view will change a lot; sometimes drastically, sometimes not, but I move a lot, it’s hard to be completely fixed. Sometimes I move objects or they get moved because I have lots of paintings going on at once and things just get moved so that I can deal with that. One painting might have a certain fabric and the other one doesn’t, so I have to put it on the bed or take it off the bed, so that makes it naturally change. The light is also dramatically shifting across the space, a lot of the recent work has been dealing with that.

NP: When you go in close, are you using sight sizing and the windows become bigger? And then you step back, the window becomes smaller? Or is it just the different angles that you’re playing with?

SP: Both happened, but neither one is a rule that I have to follow. I usually make the decisions based on how things happen in the painting.

Sometimes I’ll fight against what’s in the painting and do something drastic, but often I’m seeing how things are in conversation with what’s already there.

I might completely remove something or change my distance drastically enough that it’s going to change the composition entirely, or completely obliterate a whole area. The Wolf Interval painting is interesting because it has a lot of moments in it that were… You know when you have a part of a painting that’s a glimpse of something that excites you, and it stays there as this marker talking to you? There’s one in that painting that stayed until the end, somehow. It’s this one, dark, little strip of leaf silhouettes above the radio. That moment directed a lot of the painting, it stood as this collage in space and then other collaged-in moments in time started to happen.

NP: You have paintings that are transparent and others that are opaque and some mixed. What role does transparent painting have as compared to your more opaque painting?

SP: I start with transparent layers and try to maintain them as I paint, but usually in the process of painting they become opaque. There’s something about the density of the opaque color, how it can sit as a piece of paint on the surface, can be collage like, and is a reminder of it being abstract and how something is put together. Sometimes transparency is layered in as a different kind of light and feeling.

Untitled, 29” x 19”, Oil on linen, 2010

One of the recent paintings is entirely transparent, it was one of those paintings that just let itself stop much sooner than the other paintings would. It was almost like reaching this point of holding your breath and that was enough, without becoming dense. I’ve also been making transparent collages using silhouette paper shapes that overlap and very little else to create an illusion, barely visible contrast, no color.

NP: Can you talk about your path to becoming a more mature painter?

SP: It’s such a big question. I’ve gone through a whole gamut of figuring out how to exist in the world as an artist, how to support myself and how to keep growing and informing myself within the work. One of the most important things has been situating painting as a huge priority in my life, not avoiding it because it evades you, working things out in the studio…it’s impossible to lie to yourself, you know when you’re disconnected and you have to create a way in.

There was a period where I was still working out of my understanding of painting from when I left undergrad and I had to let go of that. Just before entering grad school I really started to wonder Am I working from perception because it’s how I was taught and it’s just what I know? Or is that really the kind of painter I am? Then in grad school, I completely turned my back on that almost the whole time. Coming out of that I was able to test everything more, just giving myself more permission.

NP: Yesterday, we were talking about the Cézanne painting of Mont Sainte-Victoire that hangs over your bed. Can you talk about its role through your career and specifically in your recent paintings?

SP: I like having paintings hanging above my bed because I like to go to sleep looking at them or wake up looking at them, to see them when my eyes are out of focus and my brain is not working yet. Apparently it’s also a good way to absorb something.

Cezanne’s influence has been more recent in my work. In the past several years I’ve been looking at Cezanne more on a personal level and it’s been coming into the work unintentionally, though consciously.

Untitled, 46” x 60”, Oil on linen, 2010

That painting in particular, found its way into the body of work that I was just doing. I became conscious of it after it was happening, and as it was happening, but I didn’t do anything to force it in an arbitrary way. After the painting was underway I began to notice the relationships to the Cezanne, it kept happening that after a day of working I’d go back home and look at the reproduction and think Oh my God, this is that composition. This is that division and this is where that light is happening. There were two that strongly related to that Cezanne, one untitled and the other titled Faldum.

The way that I’ve been painting the bed is like a landscape, so it makes sense. The palette found a relationship as well as divisions and little moments of a diagonal light where you get pulled into the painting (though the palette might rely on what fate throws my way from the thrift store as much as the Cezanne).

Low hum, 46” x 50”, Oil on linen, 2010-2011

NP: You’ve talked about the energy and the humanity and the beautiful cast of punk rock music, why punk?

SP: Ultimately I think it’s the spirit of claiming something as your own, on your own terms. There’s this openness and resistance to fitting into a narrow definition of music, art, philosophy, lifestyle. It’s working from what seems like scraping cultural bottom, reacting to it and making something out of it that’s so energetic and compelling that it’s just undeniable.

It excites me that it’s a complete renewal of these basic elements that have come to define rock music. Using the same ingredients in one sense, but coming at that in this way that’s completely different and driven. I think that, that intensity and driven aspect of it… is how I think of painting.

I want painting to be that way; working with these basic elements, paint and canvas, and working from perception, you’ve got a whole lot of history and things to work with and against, to try to bring something new to it or revolutionize it in your own small way.

NP: I had a friend say that he was always leery of realist painters, because he felt that they were hiding behind their technical skill. I would have thought the exact opposite. Somebody is hiding behind an abstraction. Do you think you’re hiding behind your paintings at all?

SP: No, I don’t. I think that technical skill is the thing we were talking about yesterday. We were saying, in “good” painting, that if you have that expectation of an outcome or how you would define something as being good, it gets in the way. And we talked about that whole thing of flourish and when you’re showing off what your hand can do; or how you can make something not just be visual but carry some meaning or gravity with it. That turns the work into something else that’s not just this thing that you do with your hand.

I feel like if anything, the paintings are like these confessions of all my inability, or some kind of record of how I struggle to understand something or come to process this thing I see.

I think of the paintings as being something that’s turned inside out, where you’re seeing all the things you’re not supposed to see. Like all the things that normally want to get concealed in a way that the painting might feel like Wow, look at how efficiently and adeptly this person created this beautiful illusion. Where mine are illusionistic, but they’re full of these weird little seams and things that aren’t really always cohesive.

Untitled, 33” x 40”, Oil on linen, 2009

NP: You’ve stated that the challenge is if you found an interesting problem, how do you stay within that problem, stay on the tracks of that problem, not get bored, don’t figure it out, but work on it; and how do you stay within that and not carry onto another idea? How do you decide if an idea is dead? And how do you decide that you’ve thought of everything you can?

SP: That question of moving on or staying within something… There have been a couple of times in the past year or two that I’ve tried really desperately to move out of the thing that I was doing; but when it’s not right, it’s not right. It almost feels like this arbitrary thing where I’m saying to myself Don’t be what you are. Be this other thing. Now is the time. And it doesn’t work. When I’ve tried it, it just doesn’t work.

I have a corner in my studio that I paint from. It’s like the little painting universe. I try to get away from this corner, this cursed corner in my studio, and I think No, there is possibility within these other places and things and I have to get away from this But I come back to this corner. It makes me crazy. I found myself doing it yesterday. Oh, look at that. Look at the light on that pattern. That’s amazing. Maybe that could be a painting. And the other part of me is saying No, no! Get away from there!

This question about when to leave things… The most important thing for me is to know when I am actually interested in investigating something or when I am trying to replicate something I’ve done before. That’s the thing I was talking about earlier when I tried to hold onto where I was when I left undergrad.

I know the difference now. So if I’m going back to [my corner], it really is that I’m still exploring, because I’ve gotten to the point where I really hated it and I thought This is the stupidest, most boring thing I could possibly do. Why am I doing this? So it really isn’t comfort.

I would say the thing is not having the expectation. For me, that is the thing that gets in the way and can keep me from growing; having some kind of expected outcome.

NP: What is your most prized art book

SP: I thought about it, and I couldn’t come up with one. I could say the Antonio Lopez [Garcia] Rizzoli book (link to this book at Barnes and Noble – note: Painting Perceptions affliate link) because I don’t own it, and I sure would like to have it. That’s really the best one I can come up with.

NP: Do you have a Lopez Garcia book?

SP: Oh, yes. I have the one from the MFA in Boston (PP affiliate Link to Antonio Lopez Garcia

by Cheryl Brutvan on Barnes and Noble

. And I have the drawing [book] (link to the Antonio Lopez Garcia: Drawings book on Barnes and Noble

. I look at them all the time.

NP: I remember that the same guy that got my Lopez-Garcia book in Spain. He had talked about how Lopez-Garcia takes the whole universe and smashes it together, and it has to hold together, maybe like an artificial diamond. And Ann Gale – And maybe your work could fall into this in that you’re splitting up the world. It’s like the world is exploding out. So one is a smashed apple together and the other one is an exploded apple out. Do you think that’s fair or accurate in any way? Would that apply to your work?

SP: I do, I absolutely do. That’s something I’m conscious of, and that’s something I’m trying to do is to get things to that point of suspension in space. It feels like each little mark hinges into the space, and into the space of the painting. I don’t know if it will stay like that, but…

I’ve reacted against it, and thought Well, that can’t be a given. I have to try to see what happens if I try to make it pull inward instead of explode outward.

Untitled, 40” x 33”, Oil on linen, 2010

Untitled, 37” x 45”, Oil on linen, 2010

Note:

There are two other excellent interviews with Stephanie Pierce that may inform you more about her work at MW Capacity and for the Jerusalem Studio School. I have tried to cover new ground with the questions with the intent to add to information about Stephanie’s work and am grateful for her generosity of her time and energy.

Thank you Neil and Stephanie for the interview. It is always interesting to read about the thoughts and processes of other painters. Stephanie your work has a sophistication that is intelligent and home-grown. I LOVE IT! You are an inspiration! I have been trying to resolve a tension between abstract doodling and classical-modern hybrid realism for over two decades now, the past years falling more and more on classically structured processes. It has not ever felt right though. I love the way you paint your way through the painterly things that arise in your process. I love your intuition, attitude and intelligence. You have given me a new opening into my own work. Thank you so much! You are truly an inspiration!

Good interview, very enjoyable work. I attended the Art Institute of Boston in 1993 and 1994 and remember Stephanie well. She was already a very committed artist, talented and doing very heart-felt painting – “the real deal” as they say!

In an art world were gimick and quick success are so over-valued, it’s good to see somene doing painting that is beautiful, perceptually rigorous, and intesely personal.