By Josiah King, guest contributor

Upon arrival at Scott Noel’s studio space at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, I was struck by the abundance of richly painted, large-scale canvases leaning against the walls. Noel, who has been working in Philadelphia since 1978, is a prolific painter of the still-life, figure, and landscape. The artist engages in the making of images through observing his subjects directly. Many of his paintings consist of constructed narratives, in which figures are engaged in roles reminiscent of ancient mythologies. I spoke with Noel about his process and mode of thinking as he was preparing for the opening of Philadelphia, a show of his work at Gross McCleaf Gallery in April, 2016.

Noel received a B.F.A. from Washington University in 1978. In addition to having over thirty solo exhibitions since 1980, Noel’s work is included in many public, private, and corporate collections. Noel has been reviewed in Art in America, American Artist, and Arts. He currently teaches figure drawing and painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he has taught since 1996.

Josiah King: For starters, I’d like to talk about your phrase, ‘the space of desire.’

Scott Noel: I group observational painters with painters that work out of their imaginations, and I set them in contrast to somebody who works a lot from, say, photographic references. You get great work anyway, I’m not dogmatic about that, but when you’re working observationally, or you’re working from your imagination, in both instances you’re tending to try to channel some kind of longing.

You just wouldn’t do anything as gratuitous as make art unless you needed it in some way. You don’t do it because you want to do it, you do it because you need to do it. What you need from art is very elusive, but it’s almost as compulsive as an itch. I’m thinking of someone like Hammershoi, or Degas, or Velasquez, or Vermeer. Part of what we recognize in their work is a kind of strange, compulsive, working out of a series of concerns or needs.

When I use the term space of desire, I talk about the way when you’re looking at something, your looking becomes kind of flawed over time. To know it, in a sense, I have to imagine it in a certain way. That act of knowing through imagination is always fueled and driven by appetite, by desire. These are people I’ve been painting for years. (gesturing towards a painting) Patrice: every time I paint her, her particular appearance is being mapped against other things I care about…such as characters in art. You really want to look at where the locus of desire in a passage is. Look at the intervals. The sense that the intervals are charged with a kind of purpose, or a kind of meaning, not in a literary sense but in a formal sense, or a figurative sense. They become animate.

In fact, there’s a great line in The Remembrance of Things Past by Proust. Near the end, where one of his characters, who is an aesthete, is on his deathbed, he’s dreaming of Vermeer’s View of Delft. What he obsessively circles on, it’s the little patch of yellow, the sunlit roof on the right hand side of the painting. He keeps talking about that little patch of yellow. I know exactly what he’s talking about. That idea of realist painting answering a need, or a longing, or a desire, is very important to me. It’s never as disinterested as just the facts.

Even Euan Uglow with that kind of compulsive act of measuring, what’s he really measuring there? He himself says that it’s really about proportion. The proportions out to the edge of the rectangle, even the decision about the proportions of the rectangle, are as profoundly expressive as figuring how to get from there to there on the face.

JK: These spaces in between – these intervals – are as important as the figures themselves?

SN: They would be. I would want them to be at least as important.

Because of the perverse way we tend to privilege things and people, I’m attracted to artists where you almost sense that the intervals are more important. Who am I thinking of? Morandi, Dickinson, Vermeer, Velasquez. There’s a certain kind of painter – Piero della Francesca – where interval is very meaningful. In fact, Edwin Dickinson actually had a specific word for this. He talked about his interest in terstices. If you look at Dickinson, you can actually find a strange fetishization of these small, tendril-like shapes that move between things. In the hands of a lesser painter or a young painter, they’ll paint something like this beautifully, and then they’ll forget how to resolve the form toward the edge.

You look at Dickinson and Morandi: you can see they’re really thinking about those places as important. You can almost see it a lot of times in my own painting. The last thing that will get painted is a reiteration of a shape, which will bring the form into focus. Once you start really looking, that’s happening all the time. I might say, in a way that I can’t account for fully, those are sights of strange, almost erotic investment.

In a certain kind of painter, maybe all great painters, things like color and shape are erotically charged. It’s not just neutral, it’s not just scripted. There’s just a kind of a deep affinity among painters where the actual stuff of their métier: shape, color, forms of elision – that’s a fancy word for editing – the translation of space and volume into shape form: those are charged categories. They’re not neutral. Every painter knows this, but most civilians do not. That’s, in a short form, what I mean by the space of desire.

Scott Noel, Portrait of Bettina, Oil on linen, 2014, 40 x 38 inches, courtesy of Gross McCleaf Gallery

JK: It’s funny how the quiet moments can be the most powerful in a painting.

SN: Well, yes, I agree, although, I wouldn’t call them quiet. Look at that Degas: that’s a study for a painting in the National Gallery called Madame Camus. Lots of young artists, and lots of really good professionals, would say, “Oh, Degas has done a really great job of off-center composing and it’s a really beautiful design.” I think it’s much more radical than that. I think Degas is in love with that abstract shape as an evocation of that wall, and it’s reciprocally related to her body as the shapes of the yin and yang symbol. I don’t think that’s just a big design decision: I think that’s…profound.

JK: I’m also intrigued about your thoughts about light, which is really important in your paintings.

SN: Absolutely.

JK: Natural light.

SN: Absolutely.

JK: You’re taking this substance, light, that you can’t really grab hold of, and you’re using a material to actually make it real, in a way.

SN: That’s the deal.

One of the civilian mistakes about light is to think in terms of a binary of light and shadow, as if they were opposed categories. Again, one of the things every painter eventually learns is that there’s no such thing as the absence of light. Every shadow has light in it. Basically, what you eventually have to formulate as an artist is a kind of theory of light. What is light as substance for you?

Most painters, especially since Vermeer and Velasquez, have been more and more inclined to see light in terms of what I would call color atmosphere. Because what we’re really after is the color of light, and light doesn’t really have a color until it passes through the prism of an atmosphere. You see how almost ludicrously attracted I am to low humidity blue skies, which – for me – they’re just the most beautiful thing in the world. I love winter for that.

One of the clichés of Impressionism is that if it’s sunny, shadows are blue or violet because, for some reason, it seems like – back with Canaletto and Velasquez – shadows were grays and then suddenly, with Impressionism, shadows become blue and violet. Well, what happened? An art historian will give you a big talk about color theory and stuff like that. Another art historian will talk about plein air painting (painting outside). What happened in that transit from a tonal interpretation of light and shadow to a more color-based one? One of the questions involved trying to figure out, what is the color of sunlight? It’s kind of obvious when you’re standing in full sun, the kind of strange heat that sunlight has, and the way it transforms different local colors, like a green and a red and a pink, into an overall golden light. Certainly, artists – at least as far back as Turner and Rembrandt – got that, so what was their interpretation of shadow in that light? Again, the Impressionists make the warm color of sunlight more explicit. You’d say, “All right, it’s only natural to make the color of shadow more explicit.” Most people tend to think of shadows as an absence of that sunlight. Every painter knows it is the absence of that sunlight, but what kind of light fills that absence? The sky.

When you cover up the sunlight, you realize that a shadowy passage on a sunny day is diffused with reflected light. In fact, it’s more beautiful, because it’s not as absolute. It’s just color ricocheting everywhere. My evolving feeling about color, with more and more appreciation of what I would call light fields or light worlds, are expressive of a reflective light source. The most obvious one is the way, on a sunny day, the blue of the sky is a second light. It’s a distinct light from the sun and, when the sun is excluded, it becomes a parallel.

The big laboratory for this is what I would call inside-outside painting. I started getting interested in painting figures silhouetted against bright light, because it was so powerful emotionally. There was something about it: it was almost cinematic in its evocative power, but you try painting a figure silhouetted against bright light, it’s a bitch because, really, what you see on a bright day is the figure almost looks like this black thing against the light. If you took a photograph of it, that’s what you’d see. If you try to photograph anybody against a light like that, to get any detail on the city-scape, you’d have to stop the exposure down so far that this would register black. To get any detail in the figure, that would blow out as a white, right?

Painters have been painting this convincingly for centuries, so what are they doing? They’re exchanging a literal value scale for a color scale. The best abstract version of this I can think of is Bonnard. Bonnard is this brilliant colorist that can get light so beautifully, but he never uses what I would call a literal value scale like Vermeer, or even Dickinson might use. When you actually go back and look at Velasquez or Rembrandt or Watteau, all the best painters, they knew it too. They just didn’t use the same color fields or the same color interpretation. It’s always color based, it’s always more radical than copying, and yet it’s profoundly tied to a sense of atmosphere that locates things in very specific depths of space. and very specific fields of light.

Whenever you think your work is about a motif, like a figure or a landscape or memory, eventually you get led to a very concrete visual question, which is, “What is your conception of the light?” My conception of light has really been increasingly filtered through a sort of love of color that is, for me, evocative. I’m absolutely convinced that I’m painting the color I see, and everybody who’s ever seen my paintings says, “Well, that’s your color.” That’s not always a friendly assessment. Some people just do not like the clichés of a given artist’s color. The joke I sometimes tell is my color…actually, as much as it’s driven by the experience of looking at nature, there’s a side of it: it’s almost like a strange Proustian memory of my mother’s interior decorating. Does that make sense? If you had in your family somebody who had a real creative bent for decoration that you liked or responded to, sometimes their color gets in your bloodstream.

JK: It’s ingrained.

SN: Yeah. There were colors that got in my bloodstream when I was a little kid, blue-greens, certain pinks, certain golds. They’ve never left. Arshile Gorky, one of the subtitles for that great artist and mother picture is How My Mother’s Apron Unfolds Through My Life. Nothing is ever just simply an empirical iteration of the facts. It’s always the facts running through experience and meaning.

JK: This meaning, or a sense of narrative, is a strong component in much of your work. Whenever you have these ideas, how do you go about realizing them? What are your steps in building a painting?

SN: In the early going I had such a reverence for artists like Degas and Reubens. I really wanted to paint complex narrative paintings, but way back then, I tried to do them and they would crash and burn very quickly. My visual imagination hadn’t been furnished with enough experience of how things look, or what’s important to you.

My process for probably the first twenty, twenty-five, years of my working life was almost relentlessly what you’re doing now: looking. I hated still-lifes when I was twenty-one. By the time I was twenty-seven, I realized this was the very best laboratory for understanding what I need to learn, so I became a pretty prolific still life painter. Still do it a lot. Lots of looking, at landscape, the figure, and still life, for years.

In my thirties and when I was forty I started to regain that courage to do narrative painting. I started heading in this direction around ’93 to ’95, when the pictures started getting bigger and more complex. I would start with places or spaces that I wanted to paint, and then those spaces would, little by little, begin to suggest mythic stories or narratives. As the spaces developed, it was very natural to just ask a model to pose here or there, then find them within the space in a way that always felt organically right. The minute a figure came into the mix, you’d almost exactly know where they should be, what they should be doing, how they should be made out of reflected light. When the figure came in, pretty quickly after that, there would usually be some sort of resonance with a story.

(Pointing to Persephone’s Departure) This story is the myth of Persephone, where Persephone is about to take leave of her mother to go to the underworld for half the year with Hades. Hades has come up at the end of the summer to collect Persephone and take her to the underworld. No one knows this shit. In fact, I have people on YouTube who, in a very sweet way, mock the preposterousness of my stories, because no one would fucking know. The stories are important to me, because they put the specific character of a place or a figure into what I would call a little archetypal dialect.

That’s one of the things that poets do. I don’t think a poet really connects with a mythic story unless they somehow recognize that story’s vibration or resonance with lived experience. At least I don’t. You know, you can find lots of examples. An arch-realist like Eakins has got all kinds of pictures where he’s trying to tell stories, like these Arcadian landscapes and those swimming hole pictures. Even the scullers are a certain kind of hero that’s set loose in a recognizable setting, like the Schuylkill River, or something like that.

Degas was certainly like that. Love those early Degas mythic history paintings, like the Daughter of Jephthah, and the Young Spartans. Those are key works, because you can see, especially with the Young Spartans, those look like a bunch of Parisian gamines set loose on the fields of Arcadia or something. The tension between the mytho-poetic and the realist is actually what is so exciting. It’s not a parody, but it’s definitely got an element of wit and humor to it. That would be another part of – I wouldn’t call it my process- but my temperament.

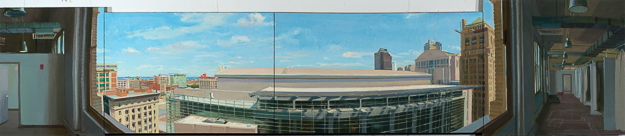

The Convention Center from the 10th Floor, Oil on linen, 36 x 156 inches, courtesy of Gross McCleaf gallery

JK: You have paintings comprised of several different canvas sizes, joined together to make one picture plane. A perfect example is The Convention Center from the 10th Floor. How did this come about?

SN: That’s a more recent development. It weirdly flows from the narrative thing. Probably about twenty years ago, I did start thinking that I loved large-scale decorative painting, but I’m really basically an easel painter. I’m somebody whose touch and temperament is tied more to the improvisation of a smaller surface. You know, if you’re doing big frescoes or giant altarpieces, you’ve got to plan those things out, because they just demand it, for all kinds of reasons.

My discovery was that I could combine the improvisation of easel painting with the grandeur of something a little bit more architectural and narrative by adding canvases. For years I did it to create a new, unified, single rectangle. About six or seven years ago, out of sheer accident, all the canvases that I had on hand were different shapes. I wanted to paint more than I had time to build the right size canvas, so I started putting them together thinking, how could I map the thing I want to paint against this composite surface? I realized that it actually worked well, because there’s a way in which, as you’re adding up the elements for the visual field, it’s almost like you zoom in or zoom out. Even the forms don’t all naturally align with a single scale rectangle. I started trying to use that as a way of deepening the experience.

I had this fantasy that sometimes these multi-canvas pictures will be broken up, panels will be lost, and I want each piece to have enough internal energy to be self-sufficient. Each moment, in a sense, has to be a germ of whatever the totality was.

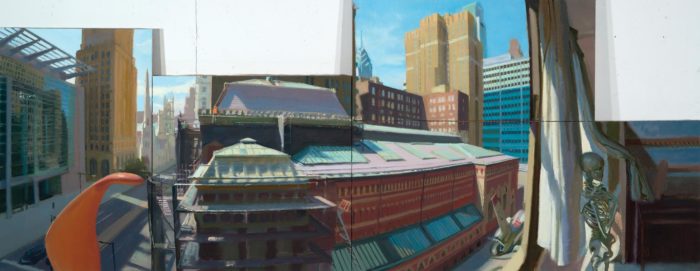

The Furness Building Restoration, 2016, Oil on linen, 32 x 94 inches, courtesy of Gross McCleaf Gallery

JK: As far as surface area on the canvas, how do you figure out what you’re going to work on for the day? Do you work in a small section?

SN: Well, I’m trying to learn to work in bigger and bigger areas. The final iteration of this, to be convincing, had to be all in one day. That doesn’t mean it’s only one day of painting, it might have been one or two statements that had to be rephrased, but that’s one layer of paint in there. If I don’t do that, I don’t get the articulation of the tones fine enough so that your eye really flows. My ambition is, above all, a sense of almost seamless flow. It is a lot like fresco painting. Fresco painting is basically giant alla prima paintings, a big watercolor painted into wet plaster. I like that idea.

The logic of this ‘all at once’ painting is my universal solvent for all the weird stuff I’ll put in the picture, even flying figures and flying objects. I found I can do the strangest things, and people will hardly even notice, because the unity of the color and the surface is enough where they just say, “Oh yeah, of course.” By the way, I think that’s what Tiepolo and Caravaggio would do, too: making the impossible completely plausible.

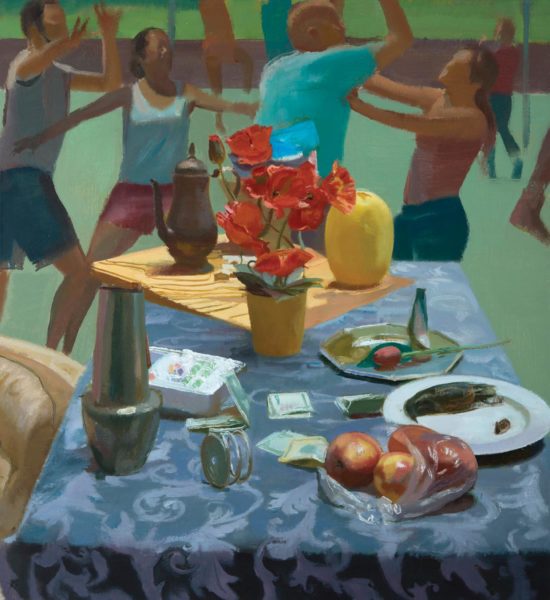

Short session paintings executed by Scott Noel during Sunday painting sessions at PAFA.

Photo Credit: Josiah King

JK: Do you have anything you want to share about where you’re moving forward?

SN: I’ve never thought that way very much. I’m one of those painters that thinks mostly from painting to painting. I want more and more to keep synthesizing the elements of this imaginative world that my painting has become. For a very long time I thought of myself as a very straightforward observational painter. I still think that’s what I essentially am, but that doesn’t fully describe what I’m doing. The paintings are becoming more and more a kind of arena to put experiences together that illuminate each other and, in that sense, become an expression of something that I want to affirm. Maybe that has to do with just how durably beautiful the world is. The world is magically beautiful, especially as it crystallizes in the occasion of a painting. One of the things that paint does is bring us to our senses, in a way that almost nothing else can do.

Painting is a pretty unique thing. It’s endangered a little bit, because if you don’t have or cherish direct experiences of paintings, you can forget what they do. Your generation does so much painting by reproduction, by the internet and stuff. You can know a lot from that, but it’s also sort of numbing after a while.

I hope to keep renewing that thing that I love about painting. That way that painting creates a world. They’re the symbol of so many domains of experience and then makes them durable, because it’s always worth remembering… Paintings don’t move; they’re still, but if they’re any good at all, they don’t feel at all still. They get your imagination moving, they get your mind moving, they get your sensuality more articulate, because they make specific and concrete all these moments of consciousness. I hope I get to be in that conversation. I absolutely know that conversation is real and powerful when I get to see Piero and Chardin. Those guys don’t seem passive to me. When I was young there was that sense of something being great, but old. They don’t seem old to me, anymore. It seems more radical and fresh than ever.

Scott Noel’s paintings can be viewed at grossmccleaf.com/artistpages/noel-t.html

Painting Perceptions greatly thanks Josiah King, for his generous, thought provoking contribution.

Josiah King is a painter working in Eastern North Carolina. His paintings focus on moments of beauty and interest in the everyday. For the past two years this focus has included the gridded, reflective surfaces of floors and walls. King is a graduate of the University of Mount Olive and Edinboro University of Pennsylvania (MFA Painting). He currently teaches art as an adjunct professor at the University of Mount Olive, Barton College, and Wilson Community College.

You can view his work at www.JosiahKing.com

(ed. note) An abbreviated version of this interview was originally printed in ShopTalk Volume 7: A Journal of Artist Interviews by MFA Candidates at Edinboro University, ed. Terry McKelvey, MFA. (View: https://issuu.com/edinboro/docs/shoptalk_web)

More on Scott Noel:

Thank you for opening Scott’s thoughts up to a wider audience. I was his classroom assistant at PAFA and he is a truly remarkable man. He conducts his life with the utmost simplicity, at the time without email or cellphone and rarely driving, in order to devote himself to his passion. I watched him paint the convention center as it was being constructed. As I recall, he worked for 40 days without a break, stopping only for a sandwich at lunchtime.

Scott’s generosity to younger painters is remarkable. When I was leaving the Academy, he gave me a gorgeous portrait in exchange for one of my small paintings. I treasure it, but his greatest gift was a piece of advice I have used thousands of times.

“Your work is never as good, or as bad, as you think it is.”