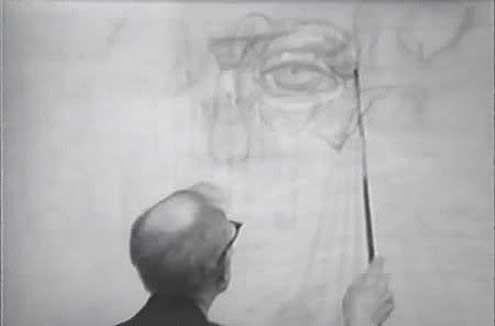

Robert Beverly Hale reciting the initial lines of Arthur O’Shaughnessy’s initial lines from Ode from his book Music and Moonlight (1874)

We are the music-makers,

And we are the dreamers of dreams;

Wandering by lone sea-breakers,

And sitting by desolate streams;

World-losers and world-forsakers

On whom the pale moon gleams:

Yet we are the movers and shakers

Of the world forever, it seems.

With wonderful deathless ditties

We build up the world’s great cities,

And out of a fabulous story

We fashion an empire’s glory;

One man with a dream, at pleasure,

Shall go forth and conquer a crown;

And three, with a new song’s measure,

Con trample a kingdom down.

We in the ages lying

In the buried past of the earth,

Built Nineveh with our sighing,

And Babel itself in our mirth;

And o’erthrew them with prophesying

To the old of the new world’s worth;

For each age is a dream that is dying,

Or one that is coming to birth.

Too often we see many legendary masters of the past century fall into obscurity due to perceived irrelevance from art schools and the larger art community. As I get the time I want to continue to help in the effort keep alive older but still important voices for younger generations of painters who wish guidance from the past to better maneuver the future. One such voice is Robert Beverly Hale (1901-1985) who among other things was an abstract painter, published poet (verse and fiction published in The New Yorker and Mademoiselle magazines) In 1949 he became curator for contemporary American art at the Metropolitan Museum. He wrote the popular book “Drawing Lessons from the Great Masters” from Amazon.com as well as translated the classic anatomy text “Artistic Anatomy” by Dr. Paul Richer from Amazon.com

. But what he is perhaps most known for is his teachings in artistic anatomy at the Art Students League of New York for over 40 years. He also taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art for many years.

Hale was born into a prominent family in Boston, one notable family member was his cousin, Buckminister Fuller. He had many luminary friends and acquaintances which over the years included such people as his artist friend, Waldo Peirce introduced Hale to some of his friends such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and James Joyce as well as the painters Picasso and Matisse. He would often relate to students stories about his early years in Europe,” recalls Richard Tsao, who was a student of his in the late 1970s. “He would recall fondly that he played chess with Duchamp or met Matisse, or that he was a neighbor of Pollock’s out in the Springs” in East Hampton, New York. (from wiki article)

In Hale’s anatomy instructions, he taught the principles of working from observation, principles of chiaroscuro and the importance of reducing forms in nature to cylinders, cubes, or spheres. Hale believes that “good painting consists of good color, good composition and good drawing. In a Time Magazine review of a show of Hale’s paintings from 1960:

Good drawing has declined tremendously in recent years, because if anyone draws well he is attacked as being sentimental or anecdotal. The result is that many teachers cannot draw well and neither can their pupils. Therefore they are doomed to create what I call geometrical or biological abstractions—Scotch plaid or turkey-dinner paintings.” Hale’s own drawings look rather like Rorschach tests that the doctor never thought of. Using India ink and a very long brush, Hale sketches in the shadows of ideas. These blotlike shadows have sensitivity and boldness—a happy combination—but what do they signify? Plenty, he says: “In some cases I think I have achieved negative realism. In a few years I think it will be possible to communicate with life on other planets around the sun. I suspect we will learn more about negative realism from the beings on other planets. Negative realism is in the subconscious. New artists must break a hole in the subconscious and go fishing there.

In a long fascinating interview with Hale by Forrest Selvig, for the Archives of American Art Hale talked about the challenge of teaching anatomy and the tradition of drawing during the height of the Abstract Expressionism, even telling how de Kooning once told him that his teaching of anatomy was ruining students. He also goes on to discuss the divisions between the conservative/traditional students and the avant-garde that has even greater interest considering that Hale himself was an abstract expressionist painter of sorts. (I’ve been unable to find any examples of his work, only written description. If anyone knows of any images please post or send a link) I will quote a few select passages from this interview related to this division between the traditional and the avant-garde that seem as timely as ever.

There was also several videos made of Hale’s popular anatomy lectures late in his career in the early 70’s I think at the Art Students League. While the quality of the videos is often marginal these videos are an important resources for anyone serious about artistic anatomy and painting the figure. Sadly, they are not readily available as the person who is selling these videos (Jo-an Pictures) for $800.00 and claims to be the copy right holder (very questionable validity to this claim according to one person whose research could find no proof of this) on this excellent Line and Colors blog post about Hale. One commenter on this thread says he was the person who filmed these lectures and gives an interesting backstory.

Some people also stated on this thread how easy it is to download all of the videos from fileshare servers for free (a simple google search will likely show how this can be done) – but you wouldn’t be able to watch more than the first two excerpt teasers on YouTube due to the person who is claiming to be the copy right holder complaining and having the entire series removed.

Robert Beverly Hale interviews, 1968 Oct. 4 – Nov. 1, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

…………

…..excerpts from the full interview

Robert Beverly Hale (RH): I’ve never had very much time to do anything much. I try to do too many things. You see, all during this time I had to keep up on the anatomy. Anatomy is a very difficult memory job, you see. And you have to keep the memory alive and fresh if you’re teaching because students ask so many questions. And also because as I teach it I draw on the great board full scale all the muscles and all the bones and all the ligaments. And I have to be exact. So I have to give some time to that. And always have. It’s something like the you have to practice.

FS Have to keep in practice. I see, I was going to make a little remark here that I didn’t think that anatomy changed much over the years, but maybe.

RH: That’s why it’s a challenging thing to teach in these changing days, you know. It’s a marvelous thing to teach traditional drawings because the rules have all been laid down. And they are known. And there can be no arguments with the students really. It’s very easy to teach that compared to something that’s going on today.

FS I’m sure that you find some students who question the need to be taught traditional drawing at all.

RH: Oh, certainly yes. Not only students. One day in East Hampton de Kooning came up to my little studio there and said that I was ruining any number of people by telling them about anatomy. But as a matter of fact, I’m not sure that he’s right. This may be rationalization, but I believe that an artist has to know the technical tradition that has preceded him. And the more he knows about it the better off he is. As I see it, of course the tradition of European art technically speaking from the point of view of studio practice remained virtually intact until the 1860’s and the 1870’s when it was suddenly attacked by Impressionists. Not technically, the didn’t do very much to the tradition except perhaps to change the light direction on individual forms they played a little with perspective. and of course they played a little with color. The Post-Impressionist followed them. They tore down a few more rules of the tradition you know. They subordinated the direction of form because they loved the canvas plane so much. But remember that all the people who did this were trained traditionally and they knew what the technical tradition of European painting was. And they used all the tricks and devices that the traditionalist had used. You might say that the Cubists followed them. And if you know the tradition you’ll see that cubism employs the traditional devices fully. They were terribly aware of planes, of light on planes, and of the sort of geometric idea that is behind the tradition in any case. There couldn’t have been any cubism if there hadn’t been the tradition. It would be impossible. So it seems to me that, as everybody knows, all art comes out of the preceding traditions. And I think it’s a help if artists know where they stand in the technical procession from the early days to the present. If they have the resources that the technical tradition gives to them I don’t think its a hindrance at all. I think its an enormous help. I’m always a little impatient with artists who don’t know how they achieve their effects and who just depend on emotion and luck to get their effects. I don’t think any good artist does. As a matter of fact, almost all the first rate contemporary artists I’ve known have been pretty darn well trained. And they know just where they stand not only in the historical tradition, but in the technical tradition. I’d like to separate the two. And I think one has to because it’s been my experience that most art historians are quite ignorant of the technical tradition. Artists however usually have quite a good idea about the history of art. But I am again and again upset by the loose way that historians of art talk about the technical tradition. They don’t know it. But you can’t know it unless you have played with it and done it and actually had the feeling in your brush or pencil. It’s a hard thing to learn. And a slow thing to learn.

RH: It’s terribly true of the vociferous avant garde group of this town. In fact what has always amazed me is the deep separation between artists during the days of the abstract expressionists they seemed to be utterly divided from the conservative artists. Certainly they never went to each other’s funerals I can assure you. And they hardly knew the name of the other group.

FS Well, wasn’t this particularly true however of the abstract expressionists more so then, well, perhaps we’ve never had a movement as overwhelming as that one was.

RH: I don’t believe we ever had.

FS And this included not only the artists themselves but writers, museum people, a great commitment all over, all across the board.

RH: Yes, a great division.

FS They divided themselves from everybody else certainly but won the day and ruled for a good long time.

RH: Well, of course it did, again in the minds of the avant garde. but the others went blithely along ignoring it. This has interested me deeply psychologically you might say because I have to know both groups, you see. Well as I was saying, I might give a dinner party here to a group of prominent conservative artists and they’d never heard of Kline and Pollock and the others, you know. Whereas I would have that set and they would never have heard of Leon Kroll or Isabel Bishop. They were very divided. It seemed to the preposterous but that’s the way people are I think.

FS It’s a little harder for me to see how the established traditional artists would not have heard of the newer ones because they had such a big press, Art News and so on.

RH: Well, they didn’t like to read Art News undoubtedly or allow it to come into the house. The bulletins from the Modern Museum were also disturbing. They lived in an ivory tower. The National Academy is still going up there carrying on its own business and ignoring the rest of the world, having their little shows that nobody comes to giving out their prizes.

Daniel Greene, Portrait of Robert Beverly Hale, 1976, pastel, 50 x 36 in

FS It’s interesting to think of their school in relation to the Art Students League. RB:Well, it is fascinating yes. But I don’t think it’s so bad because I do feel that artists should have an understanding of what the tradition is, you see. I know I paint rather wildly myself but when it comes to teaching I like to start off with the traditional fundamentals.

FS But in the Art Students League I’m sure that they’re urged to go up I’m sure that you especially would urge the students to go up to the Metropolitan to see the exhibitions.

RH: Oh, of course, yes.

FS And other teachers would as well.

RH: Oh, I’m sure. The strange thing about the League is that almost all young people are strangely conservative at heart when they first show up at the League and they join the conservative clauses. But bit by bit they become sophisticated I think largely through talking to the other students. And they find out about the whole history of art and especially the history of the last fifty years and they begin to experiment and move on. But largely they start out in the conservative classes. They always seem to have a historical sense that way.

FS They perhaps feel more at home with it too.

RH: Well, in the beginning, you know, they’re really fairly simple-minded when they turn up, most of them. They’re young and they don’t know how the art world is put together or they don’t really know much about what art is. They have a feeling that it’s the representative of so-called reality. That seems to be what they try to learn first. Since I teach that, why I get a great many of the new ones, the beginners, and try to start them on their way. But I try to point out to them that there are other places to go besides the traditional.

Oral history interview with Robert Beverly Hale, 1968 Oct. 4-Nov. 1, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

e

Please consider; If you purchase the book(s) from the Amazon links in this article (or any other additional book bought during the same session of shopping on Amazon) this blog will get a small percentage of the sale and will help to support future articles of this nature and more.

Isn’t that odd. de Kooning himself had some years of academic training. Still it seems he largely got his way.

I’m going to have to figure out how to get the lecture videos. I have the books, but always have thought a complete transcription would have been much more valuable. Little did I know recordings existed!

I’m not sure anatomy in the extreme is very valuable aside from the study of good design. The big bones and muscle groups and general morphology are helpful to understandd. But Dr. Richter’s book just inspires MEGO, in my opinion. And Bridgman, caricature. I’m much more curious about Reginald Marsh’s contribution to the stack. Thanks for the very cool video.

The videos are currently available (free) on Demonoid. There are 20 seeders as I write this. And soon there will be even more. 🙂 I hope “Jo-An” never sees another penny.

Senatorial Committee on Outer Space (1960)

Ink on paper, 22 x 28 inches, signed and dated “Robert B. Hale ’60” lower right

http://www.caldwellgallery.com/hale_outer_space.html?gclid=CJGgvYCJ9KgCFcOd7QodUX1cSA

Wow, thank you RT for posting this link, excellent find.. (I will update the article to include this image later today) It is interesting to read Hale’s description of his work and then see this image – came fairly close to what my mind imagined it looked like. Katherine, thanks for the information about Demonoid – this should prove useful to people wanting to learn about anatomy from one of the great teachers of it.

I attended figure drawing classes at the Art Students League of New York in 1968 & ’69. Though I miss Robert Beverly Hale’s classes, I picked up his book “Drawing Lessons from the Great Masters” at their bookstore. It had the best reproductions I’d ever seen of classic figure work and became my bible for the next few years. I still have my copy, well worn and still much loved. This guy remains one of my best teachers ever though we never met, at least not in the flesh. I’d recommend that book to anyone!

To those of us who had the good fortune to attend Hale’s classes this is fine post and tribute to him.

Just one inquiry if you don;t mind, the video and the text do not match. Hale uses the word “and two” instead of “and three” in one line, and in the next he uses “empire” and the text reflects I assume the original word of “kingdom” used by O’Shaughnessy’s verse. I must admit empire has a more universal appeal.

Again my thanks to you.

I studied with Hale from 1967 through 1972 and am currently working on creating a digital version of his teachings.

I studied at the Art Students League circa 1972 to 1974. Robert Beverly Hale was my primary instructor. He is one of the great influencers on my life and on the evolution of my intellect. Hale would say, “You see what you understand.” I learned how to see through a form and how to conceptualize space. The most important artistic thing that I learned from Hale was how to look at light. That “awakening” has been present in my daily life ever since. He also opened the door to the relationship between Art and Poetry. He would end his lectures with a poem. It was wonderful to sit with him alone in the gallery and talk about things like women and his relationship with Jackson Pollock. He made the life of an artist sound and feel important and valueable. Feeling valued and important was a last gift that he shared.