Simon Dinnerstein is a Brooklyn-based painter and graphic artist. He has a B.A. in history from the City College of New York, and continued his studies in painting and drawing at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. Dinnerstein is a recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Germany, the Rome Prize for living and working in Italy at the American Academy in Rome, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Grant, the Ingram Merrill Award for Painting, a New York State Foundation for the Arts Grant, and three Childe Hassam Purchase Awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He has been represented in New York by Staempfli Gallery and ACA Galleries. His work is included in numerous private and public collections. To learn more about Simon Dinnerstein and view other examples of his work, visit his website here.

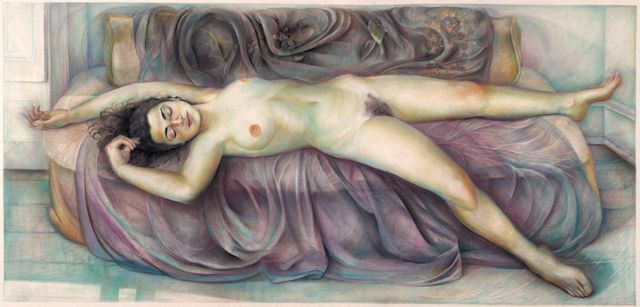

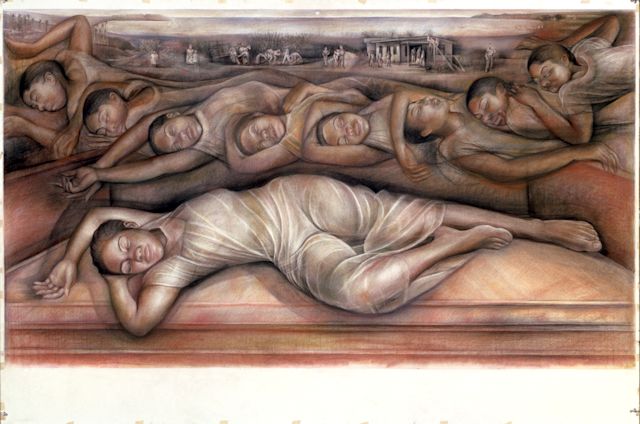

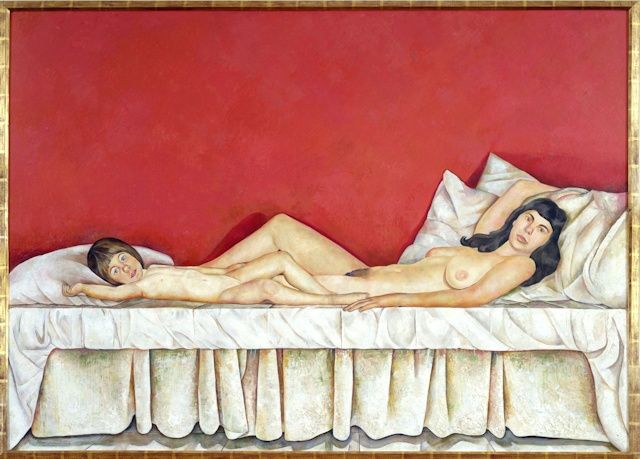

Simon Dinnerstein’s work is marked by a strong graphic line used in the service of a geometric and patterned ordering of visual information, harkening back to his start as a printmaker. Later work moves toward silvery tones, his people not so much flesh and blood as fantastical glowing constructions of mother-of-pearl. In still-lifes and figure paintings, drapery twirls and undulates, more active and aggressive than the ephemeral, lounging women, fruit, or flowers, passively presented for consumption. Dinnerstein’s work holds a tension between observation and construction, between delicacy of tone and rigidity of structure.

I am conducting this interview with Mr. Dinnerstein on the occasion of the showing of his large, early painting, The Fulbright Triptych, in the German Consulate in New York City. The painting will be on display at the Consulate through March 31st, 2014, at 871 United Nations Plaza, First Avenue and 49th Street. It is open Monday through Friday, from 9 am to 5 pm. I also had the pleasure of reading Daniel Slager’s 2011 edited volume The Suspension of Time: Reflections on Simon Dinnerstein and The Fulbright Triptych, which contains forty-five essays by a wide variety of authors, such as Jhumpa Lahiri, Edward Sullivan, Thomas Messer, George Staempfli, Guy Davenport, Juliette Aristides, Anthony Doerr, George Crumb, and John Turturro, written in response to their viewing of The Fulbright Triptych. I refer to quotes from this book at various times throughout our discussion.

Before diving into the discussion, I would like to share, in his own words, Simon’s remarkable account of the situation surrounding the purchase of The Fulbright Triptych.

I came back from my year on a Fulbright Grant to Germany in 1971 with my Triptych in its beginning stages. The painting is 14 feet in width. I spent about a year working on it and the middle panel was about 2/3, possibly 3/4 complete. Unfortunately, we then had quite a financial crisis and I absolutely couldn’t figure out how to support my family. My daughter was an infant, perhaps 9 months old. I don’t have a trust account or an inheritance and so I had no back up at all.

I remembered seeing Antonio López García’s exhibit at Staempfli Gallery and, in a kind of crazy, desperate act, put some photographs together and decided to go to this gallery. I didn’t have an introduction and I literally walked in off the street. It was the first gallery I had approached. The gallery was very fancy, was located at Madison and East 77th Street and was on the second floor, so you had to know where it was, so to speak. There I met Phillip Bruno, who was the assistant to George Staempfli, and whose role, I believe, was to ward people off. I showed Phillip the photos and mentioned that I had seen an exhibit five years before of Antonio López García and thought that there was some common thread in my work with that of López. Phillip looked through the images I presented and told me that he would like to show the images to George. A few days later, I got a phone call, expressing their interest in coming to Brooklyn to see my work. Brooklyn then wasn’t the same as Brooklyn now, which is clearly a very hot commodity. I think in 1973, Brooklyn was, for Staempfli, further away from upper Madison Avenue than Paris was.

In any event, both gentlemen (tall and imposing types) came to my apartment in Brooklyn and then to my studio, which was located in the nearby Sunset Park, a very working-class neighborhood. They spent a good deal of time looking at the Triptych and literally didn’t say one word. This went on for almost one half hour. Then George looked at me and said: “This is a great painting and I would like to own it.” I was, to say the least, quite stunned and knocked off my feet. I asked them what I could do, what did they mean, etc. They put on their coats and walked down the stairs, and were on the street level, where they waived for a cab. Phillip turned to me and said that I shouldn’t get in touch with them, they would contact me.

I called my wife right after and recounted the whole series of events to Renée. I was quite dumbfounded. About four days went by and I received a very well written letter from George. He told me that he and Phillip had been very impressed with my work, especially the large unfinished Triptych. He then told me that he wanted to buy the work in its unfinished state. He mentioned that this was probably a crazy idea but that he had a strong feeling about my work and very positive instincts about my finishing this painting.

He sent me a check every month (exactly on the First) for the next 2 years and then I had my first exhibit there. So, this was quite an event…what one might call a deus ex machina. A first class rescue…an eerie intervention. And, it was chiefly due to Antonio López García’s exhibit. So, my admiration for López’s work, which is quite high, has also a very special personal dimension. This is quite a fairy tale kind of story. Somehow, I think that you can grasp its great significance.

Click on the above image for a larger version.

Elana Hagler: Thank you for this opportunity to get to know you and your artwork better, Simon. To me, your work embodies a Northern European and Germanic sensibility, one which embraces order and a certain sense of reserve that leans towards flatness and linear elements. This is opposed to a more Italian/Mediterranean hot-blooded passion and fullness of form—the voluptuousness of Valori Plastici (“plastic values”). Even though your later work definitely ventures into the erotic, it does so through a very patterned and linear lens. How did your time in both Germany and Italy affect you stylistically?

Simon Dinnerstein: I think you are right about the northern point of view, but I would also add to your characterization, an instinct toward a formal approach, an architectural sense of space, possibly leaning in the direction of abstraction in the creation of form. For instance, there is the influence of such artists as Ingres, Piero, van der Weyden, Holbein, and George de la Tour. There is certainly some direction that comes from Italy, in terms of volume, palpability of form and a caressing and sensual direction. I can see this in works such as A and Portrait of A and Passage of the Moon.

I can see threads in my work that come from these enormously influential visits to Europe. It’s hard to pin down, but there is some sense of Europe in the work. Sometimes this influence is a coincidence, something I would have arrived at without the experience of my trips. At other times, there is a clear, recognizable influence of a particularly European point of view. For instance, Anthony Clark, former director of European Painting at the Metropolitan Museum, after seeing my work in my studio at the American Academy in Rome, asked me if I knew the work of Stanley Spencer. I had never heard of the artist, but shortly after the visit, I looked up Spencer and could see why this artist came to mind. The same might be true for the Italian artist, Felice Casorati, who is very singular and intriguing. Also, there is clearly a surreal side in these works, which come from surrealism and its European roots. This interest in dream imagery and the real and unreal are manifest in the drawings Purple Haze and Night and even Passage of the Moon.

I read just recently of a new exhibit of the work of Dürer that opened in Washington. Holland Cotter wrote of the influence of trips to Italy on Dürer’s work. I hadn’t thought of this before, but I think this is true. Dürer is a great favorite, a real hero of mine.

EH: In her essay, your daughter Simone wrote, “My father’s primary interest in art is in its humanity. He is not drawn to the surface of his subjects, to the rendering. He is interested in the life of things….He isn’t concerned with the historical context of a painting, or the color theory behind it, or the iconography within it.” Can you tell us more about what is meant by the “humanity” of paintings that so attracts you?

SD: Simone’s comments here regarding “the life of things” are wonderfully perceptive. If one could make an analogy between painting and writing, a really good writer brings us life and humanity in all of its many directions. A male writer can inhabit and describe the life of a grandmother, a woman, a little girl, and a baby. He can, as well, present moods which are quite dark, marvelously light, strangely surreal, and dreamlike. He can be an apple, a pear, a pod from a sycamore tree, the last half inch of a pencil, an imploring and wistful dog. This ability to channel all of these divergent states, from the splendidness of the good to just plain poor or evil, is what is the humanity that is in art, whether it is painting or music or writing. It seems to me that artists that are really good can elicit these forces, acting perhaps as conduits, to bring forth this humanity.

Perhaps the ‘lives of things’ is Kabbalah-like, that is, a search for the mystery and vibration below the surface. It is the energy and vibration that resides within inert forms. Possibly, this underside is the root of the humanity that we strive to evoke in art. In any case, it’s what I am drawn to.

EH: In the 1975 Catalogue Introduction to your first solo exhibition at Staempfli Gallery, George Staempfli writes that you recreate the subject “with intense realism, exactly the way [you see] it, without softening or embellishment, without artistic liberty.” I do not agree with this take on your work. I’ve already pointed out the linear quality of your art, and when I look at the cloth of your more recent work, in particular, it seems to undulate and take on a geometric, rhythmic life of its own. I wonder to what extent the various formal manipulations you make are conscious or unconscious.

SD: I understand what George Staempfli means, but in fact, the creation of art is much more complicated. If one takes as an example the writing of Thomas Mann and one reads it quickly, it seems descriptive and naturalistic. However, if you stop and think about Tonio Kröger or Death in Venice, for instance, the story is full of selections of information, the paring down of reality and multiple artistic decisions. From my point of view, this concept of selectivity works incredibly well in fine art, if some larger architectural form, which might encompass space and composition, surrounds it. Some kind of craziness or strangeness should also be present; perhaps an instinct for the irrational. The art then contains the signature of this individual or artist; it’s the DNA, the mysterious center.

Thus, we can see the weakness of rendering…we need it to convince the viewer, but the downside is that it is the part of the fine arts that can be taught…rather than the X that can’t be. In a certain direction of figurative art there strikes me as a confusion between means and ends. The rendering is mistaken for art. Rendering should act as a window. It’s a means to find the mystery that is in the art.

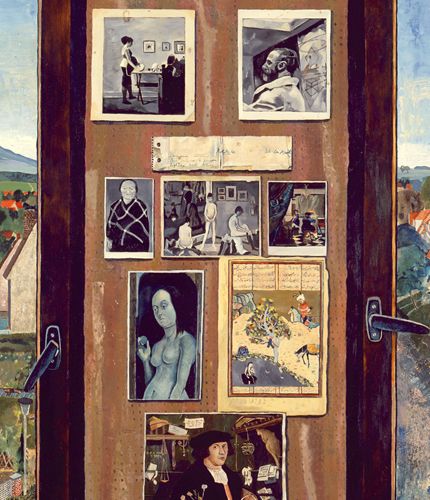

A slight aside. Some of the viewers of my triptych comment on the many reproductions on the wall and ask if they are collaged. Are they pasted on? No, they are all painted. And, yet, to my eye, the work doesn’t seem trompe l’oeil in character. So, for instance in the works of artists such as Harnett and Peto, which depict a piece of paper or a tool on a wall, a pipe for smoking, the goal is to dazzle, to fool the eye by some bravura technique. It’s very dramatic and eye-catching but where are we once we ‘get’ the image? My sense is that the reproductions in the Triptych, though very illusionistic, move on a different track. They act as portals, so we travel through the image to the other side or between the images, to ask why or Y?

EH: In your interview in the book, referring to the Fulbright Triptych, you mention that the imagery came to you “at one shot in its totality.” Is this different than the way your impulses for other artworks have taken form? Could you tell us something about your process, from inception, through the middle game, to the fulfillment of an artwork?

SD: To begin with, the vision of the Triptych came from a scene that was partially in front of me. I found myself sitting in front of a window, working on an engraving. I moved my chair back and saw this grouping of objects: the table, windows, reproductions, windows, landscape. Compared to the completed painting, about half the objects on the table were present and half the reproductions on the wall. I remember thinking that the scene would make for a fine painting, an image that I saw in color, as opposed to the black and white drawings I had been working on. Right from the start, I saw the need for the composition to take the form of a triptych. I imagined Renée in the left panel and myself in the right one. The actual architecture in the room wouldn’t have allowed for this much space. My hunch was that the wings would push the viewer’s eye out to the periphery. Furthermore, the wings appeared in my imagination to be somewhat warmer than the middle panel. Thus, I reasoned, the dialogue between the middle and the wings would create a new temperature and conversation. Initially, I saw the Triptych all of a piece in its entirety, certainly some type of strange eidetic way of seeing. In my mind’s eye, the total width of the painting was a quite astonishing 14 feet. Looking back, it seems mind-boggling that I thought that I had the abilities to execute this vision.

My daughter, Simone, wasn’t born at this point and the plan was for Renée to be holding something else. There are no studies for the piece. I ordered the panel, which is virtually 80 x 80 inches. I primed and gessoed it and just started drawing. I drew it directly in fine lines with a rapidograph pen. When I finished the drawing, all of the elements were drawn out on a large ivory white panel. It was crated, sent with us on the ship, the S.S. Rotterdam, and delivered to our Brooklyn apartment.

For many of my larger works I do have at least one or more studies. The studies give me a sense of the scale, the space and composition. I try to concentrate on the composition first. When all is said and done the stronger the composition is, the more eye-catching the painting is. I usually work on a ground, which might be a gray-green or a purple-grey, etc. I prefer the ground to be interesting, but mottled in tone. I like letting it show or breathe through. The Triptych, conversely, used a high key white ground.

For me, I think the images are the strongest when you can visualize them. There are some changes, of course, but when the image stretches onto your eye and pulls at you, even if it is a very odd or strange image, the work has more frisson to it, some extra mysterious karma. It calls you.

EH: In your letter to William Hull, the director of Penn State’s Art Museum, you mention the concepts of “seeing” vs. “perceiving.” Specifically, you talk about “seeing closely—seeing significantly vs. seeing closely and not seeing at all.” Could you elaborate?

SD: In some sense, perhaps in the most transcendent way, the Triptych is about consciousness and perception. It’s about the way visual imagery frames our references to life. It follows then that the more we see the more conscious we are. I am not sure if consciousness can be measured or how we would communicate information about this state of mind. A recent article in the Atlantic, by Joshua Lang, dealt with anesthesia as a part of a range which was defined as consciousness. The essay spoke about the doctor’s need to measure consciousness to determine if the anesthesia was actually working. My hunch is that consciousness varies greatly among people. So, how do we understand things? It is through the degree of visualizing and thus being there, that leads to a hyper-conscious state. So, if one keeps with this line of thinking, it would seem to me that many people look and see, but don’t perceive. Or, putting it another way, their practice of looking is casual and fuzzy. So, we could say that the Triptych deals with this issue: instruments for measuring and perceiving, reproductions, all set up for us to find our way, to discover who we are. Many years later, it occurred to me that some mysterious connection existed between aspects of the painting and Dürer’s Melancholia. It was years after the completion of the Triptych that this thought occurred to me.

Your question is mixed in my brain with the experience of a recent visit to the German Consulate to meet some guests who have been invited to see The Fulbright Triptych. If one was paranoid, (and Jewish?) would the wish for a high level of consciousness be tied to Germany and the Holocaust? If I was living in Germany in 1942, would a great degree of consciousness have saved me or did it matter at all? Is surviving just a matter of luck and fate?

EH: In the interview, you describe The Fulbright Triptych as “the intimate depiction of a family, as ‘idea,’ and as pinpointed and ‘held’ in time, living together and striving to understand and ‘get at’ what is ‘out there.’” I can definitely relate to this very strongly. My daughter is two years old right now…just a touch older than Simone was when you competed the painting. Counting my four-year-old son and my husband, there are four of us that form this unit that is struggling to define itself in relation to the outside world, which counterintuitively seems to be getting more mysterious as we experience more of it. What are the ways in which family and art intersect for you?

SD: I don’t think I have consciously thought of this notion. You put this very well. Yet, I suppose the answer really is in the painting. The art historian Albert Boime titled his essay Simon Dinnerstein’s Family Romance. There certainly is something to this notion. Possibly it’s a way that we fall back on this world of family to protect ourselves and make sense of what is out there. We create a reality, a smaller reality, which helps us to understand or deal with the larger one. I suppose in the Triptych one could say that the visual information, the visual baggage, is helping this individual and family to define itself. Thus, there are multiple realities. There probably or surely is some objective reality to begin with. Then, there is some sense of a family and their particular take on reality. Then there exists the incredible variations of, and between, families with their differing takes on reality. Even further, in the latter case, there is the idea that the reality depicted in the Triptych exists just at one point in time. It is fluid and changing. That is why the varying reproductions that were chosen would be different now. Possibly they would have started to change within 6 months after the completion of the Triptych. We aren’t still-lifes (or still lives!).

How to make sense of all of these simultaneous realities? The answer seems to point in the direction of, curiously, greater consciousness and increased humility. This notion is reiterated in the reproduction of the small quote in the Triptych’s middle panel which can be seen next to the aerogramme:

And to the question which of our worlds will then be the world, there

is no answer. For the answer would have to be given in a language, and

a language must be rooted in some collection of forms of life, and

every particular form of life could be other than it is.

-Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

EH: Later in the interview, you refer to “the belief that paint can yield ‘spirit.’” I would love to hear more about that.

SD: Even though there seems to be somewhat of a return to the figurative tradition, I have the overriding sense that the great forces that once put human beings at the center of art have been somehow disconnected from the centrality of art. From a critical and ‘with it’ standpoint, figurative art has taken quite a hit in the last 50 years. The centrality of the human being in the fine arts just isn’t there. My guess is that Picasso and Matisse, revolutionaries in mind and paint, would concede this point. If one visits a highly touted contemporary museum today, one can go from room to room and not see an image of a human being. A year ago I attended a meeting at the National Academy in New York. Members of the organization gathered to vote on prospective nominees. I was struck by the prevalence of the same point of view that I see when visiting museums. At the meeting, various artist members got up to speak about their prospective nominees. The projecting of slides of the nominees work preceded this presentation. After a very sad two hours of this, I found myself remarking to an artist friend, “What happened to the human being? I didn’t see any sign of life (human, that is) in 96% of these presentations.”

I am very interested in this humanity, a living humanity that I described before. When I choose to find art that depicts the full measure of a human being, I find myself turning to the world of film. Here, also, the concern isn’t over riding, but nevertheless it is there. For instance, the recent Michael Hanneke film Amour is clearly an example of a really deep work of art about the human spirit.

So, I would like to hold out the possibility that there are instances where paint (and also charcoal, carbon, etc.) will somehow reach past the medium and reveal spirit. Here, a number of artists come to mind: Balthus, Lucian Freud, Antonio López García, Anselm Kiefer, George Tooker, Gregory Gillespie, Edwin Dickinson, Lennart Anderson, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Ron Mueck, El Anatsui. Somehow, they have broken through and gone past the paint to find the window to spirit. And this spirit isn’t mushy or sentimental or illustrative: it’s modern, tough-minded, committed and human.

EH: One tends to think of painters as building up to a monumental work—you started off with one. After such an undertaking, and the remarkable story of its purchase and the subsequent patronage of the Staempfli Gallery, what was it like to get back to daily work in the studio?

SD: In a long career connected with the fine arts, one can see clearly that there is a certain ebb and flow. Sometimes things go in a much more excited way. With a particular work, one becomes obsessively involved and committed. Sometimes things are quieter, but the commitment is there. Something about the Triptych always seemed as if it was a painting located in a fairy tale. The conception of the work seemed extraordinarily lucky.

Such a large painting, appearing in such a magical way, all of a piece, without a single study, was quite an extraordinary experience for me. George Staempfli’s purchase of the work, in its unfinished state, had all the workings of a deux ex machina, right out of some Greek play. The painting’s origin in post-war Germany, of all places, is extremely counterintuitive. Many of these events placed an incredible pressure on me to somehow get this painting to be extra, to be extraordinary, to push it and create an extreme and extra committed work of art. I think some of this pushed aspect seems to me to be cemented into the fabric of the painting. When one is under such pressure, you are really too worked up to enjoy (whatever that word means) what you are doing. You are nervous, running on adrenalin and full of doubt. Can I actually put this all together and realize this vision?

There are a number of other examples of works which have had similar tensions and demands – In Sleep, Night, At the Still Point, Purple Haze, Solaris, where there is something special or perhaps eerie going on. You aren’t quite in control; it’s not quite rational. You feel a shiver and some surreal jolt. Someone is holding your hand as you work, leading you along. You couldn’t possibly have thought of this idea on your own.

I think the important thing to understand is that pictures have different heartbeats and motivations. Perhaps some are akin to novels, some metaphysical, some visionary, some short stories, and of course there are poems, diary jottings and personal notes. I think the artist should listen for some vibration and make sure that he or she is listening hard. The Fulbright Triptych at 14 feet is just the right size and A Carnation for Simone at 6 inches is just the right size. I have seen a good many paintings that are just blown up to over-size dimensions, to give them a greater sense of their ( not so weighty) presence.

EH: I’ve been enjoying picking quotes of yours from the book on which I want to hear you elaborate further. You talk about “really looking at something, and through that intense looking, we are becoming who we are. We are becoming ourselves. We are becoming the best of ourselves that we can be.” Now, this deeply resonates with me, and, I’m sure, with many of our readers here at Painting Perceptions. How do you believe that the act of intense observation is linked to self-actualization?

SD: I think that one of the things that drove me in the direction of the fine arts in the first place is that I seem to have a very finely tuned visual memory. For some reason, once I see a painting or drawing I can remember it. The same is true of faces and things. So, I am prejudiced about looking and seeing. I am particularly interested in the eye and consciousness. I even gravitate to focusing on the depiction of the eye in portraits, say of Rembrandt, Van Gogh, van Eyck.

Until fairly recently, I never realized how great were the varieties of eyesight, both looking outward and inward. I remember reading a quote from Van Gogh where he remarked that the human eye was more interesting to him than a cathedral. I guess what he meant was that the eye is so small and yet it is so much greater in scale than one of those imposing European cathedrals. A chance conversation with my cousin, a chess whiz, revealed that when he plays chess, based on the notations in the newspaper, he doesn’t visualize the pieces at all. In fact, he remarked that he has difficulty picturing anything. I asked him about his mother and father, that is, could he dial up an image of them in his mind and the answer was that he couldn’t.

So, I guess, unlike my chess-playing cousin, I am prejudiced toward the visual. In a certain way, therefore, being an observer is all we have, pushing us to figure out what is “out there.” So, I have the clear sense that the better we see, the more we are conscious and the more we are becoming who we are. Intense seeing means that we are living hard, that we are really taking it in, that we are getting our money’s worth, here in this game on Planet Earth.

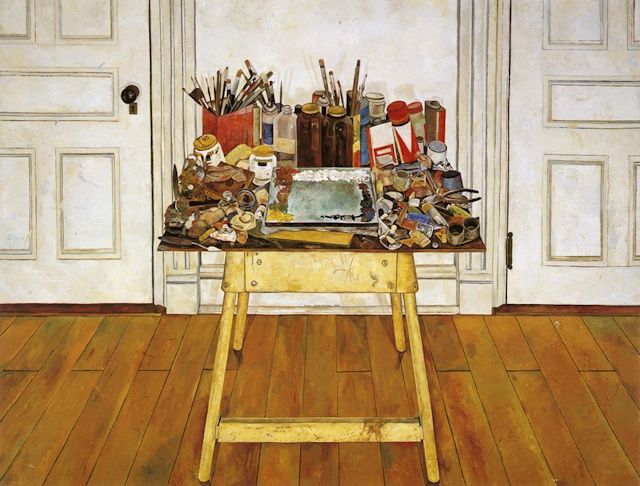

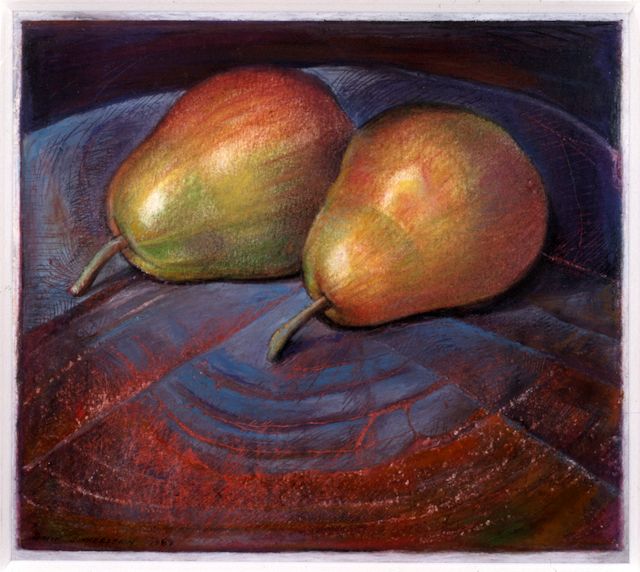

Mid-Summer, 1987, conté crayon, colored pencil, pastel, 36 1/2 x 51 3/4 inches

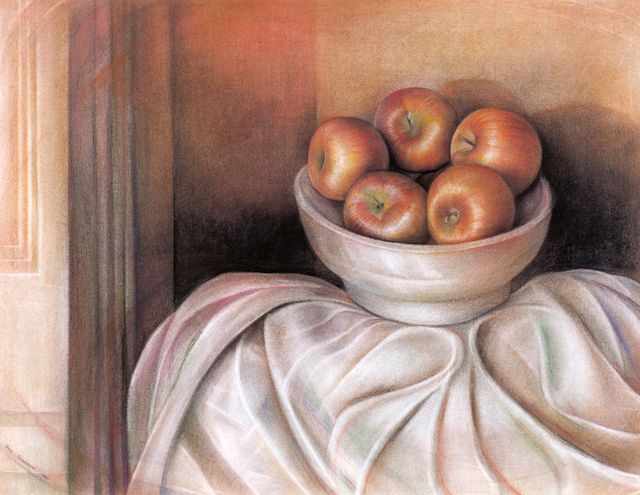

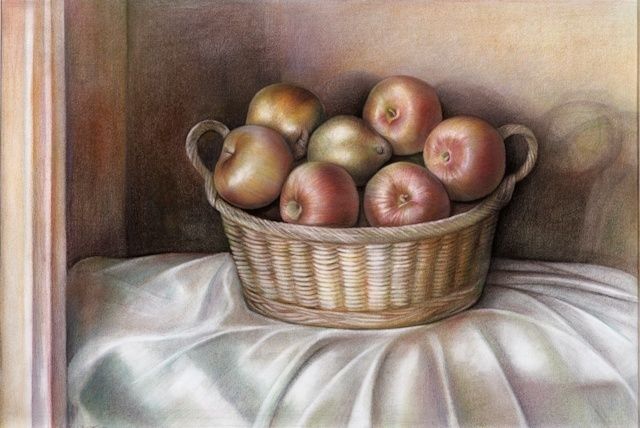

Rome Beauties, 1985, conté crayon, colored pencil, pastel, 20 x 25 inches

I like your work. I’m reminded of many things and the phrase, “Deus est sphaera infinita cuius centrum est ubique, circumferentia nusquam.” Not god the deity, but that everything appears to have its own centre, the stapler on the desk that I’m staring at has its own centre, the parts of the stapler have its own centres. Trying to depict Aristotle’s notion of unity, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” isn’t exactly the answer when attempting to describe perception; it doesn’t fit as nice as I ponder the stapler. Anyways, you’ve made some beautiful work, especially the “Mid-Summer”. Also, now that I think of it there might not be just “one” entire “consciousness” that is divide up among everything that goes back into one entity; there just might be a whole lot of centres, or middles. A universe full of things that can be abstractly reduced to middles that like bumping into each other. -jewell

Dear David:

Many thanks for your fascinating response. I was in Washington last week to see the Durer exhibit. I greatly admire his work and found myself spending a good deal of time with his spectacular engraving Melancholia. Here, one can see an intense depiction of an hourglass, a woman, a magic square, calipers, the landscape, a dog, etc. The centre of each of these objects is intimately realized. Each form is “occupied” by the artist. Amazingly, each object, one next to each other, works beautifully, and the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Also, the whole has a design format that takes over, that supersedes the details. “A universe full of things that can be abstractly reduced to middles that like bumping into each other.” The total size of this mind-boggling work is less than 10 inches in height.

A part of Elana’s discussion dealt with light and the development of my work. I mentioned that I thought the light in the earlier work, The Fulbright Triptych, was that of a graphic artist. Thus, when I saw Durer’s work and especially some of the prints, I could see some shared approach to visual reality. “Not god the deity, but that everything appears to have its own centre.” your quote

Here is a site with a number of details of The Fulbright Triptych: simondinnerstein.com/news.html just below the image of the Triptych. The painting is 14 feet wide and I hope you can see it as its exhibit at the German Consulate in New York has been extended until March 31, 2014.

Also: see the drawing, Marie Bilderl: simondinnerstein.com/marie_bilderl.html 49″ wide

Arnold: simondinnerstein.com/arnold.html 84″ high