This is the first article for the new section on materials and technique, “Sounding Technical”. The first thing I need to say is that I’m no expert about the technical aspects of painting. What I hope to offer is a non-partisan centralized source of knowledge and opinion to help in the learning and promotion of sound painting principles.

Naturally there are many resources online to learn about specific technical concerns related to painting, too many resources actually, I’d like to find and share the most useful and informative sites related to the issue focused on. My focus will generally not be to advocate any particular method but rather look at the best arguments from differing opinions about any one subject. Eventually, I’d also like to hold interviews with painters and others about specific technical issues as well as encouraging guest writers to speak on a technical matter when possible.

Practical, sound advice is all well and good but I also relish reading about the controversial, the offbeat, and the contrarian points of view. I’d like to offer topics that incites or inspires discussion. Many times when I’m reading online Op-Ed columns the comments are often more interesting than the article itself. I’m certain that many readers here hold a vast knowledge base as well as strong opinions,if shared, could offer an important resource for painters.

My first article will take a look at some thoughts on varnishing oil paintings both pro and con.

It would be most curious to see the results of a survey showing what percentage of completed contemporary paintings are varnished. My guess is that it would be on the low side. Modernistic oil painting on traditional supports has often sought a less precious, matt, rough or complex surface texture where a shiny varnish could significantly detract from the desired look. Some might even say a glossy varnish makes the painting look too slick or makes the painting difficult to see from the glare. Some painters may fear a varnish might make the painting look too “traditional” or fear the painting won’t been respected enough as a flat surface and the varnish suggests more of a glassy window onto the world rather than the modern notion of a richly textured object covered with colored glue. But all flat object are going to collect dust and face environmental risks that over time will damage the unprotected painting.

On the other hand, many painters prefer the look of the glossy varnish and the way it tends to deepen and saturate the color and appreciate the way it unifies the surface and may not feel the painting looks complete until after varnishing. No doubt there are a wide range of opinion regard the use of varnishing and it is interesting to hear some thoughts both pro and con.

It is commonly written that oil paintings should be varnished anywhere from 6 months to a year after completion, using any number from a wide variety of varnishes in order to protect the paint surface from environmental damage such as smoke, pollution, etc, help even out the surface and eliminating any “sunken-in areas”, restore the “wet” painting look, enhance the vibrancy and unity of the colors and to give “finish” to the painting. (actually varnishing doesn’t really eliminate sunken-in areas or the uneven sheen that results from oil being leeched out of the paint – it will make the sunken-in matt areas more glossy but will also make the glossy areas even more glossy – defeating your purpose. I’ve heard it is better to “oil-out” the sunken in areas long before applying the varnish or better yet to prevent sinking-in by better preparation of the ground. Here is a link to a Winsor-Newton video that discusses dealing with “oiling-out” the “sinking-in” of colors in a painting.

I would venture to guess that most painters today prefer to use the modern synthetic varnishes as they are less apt to yellow or darken, are easier to apply successfully and will allow for relative easy removal with less risk to underlying paint layers. Modern varnishes offer a wide variety of solutions to protect the painting from dust, scratches and other such harm. They also offer a range of finishes from glossy to matt.

Some painters still prefer older varnishes made of organic resins for a number of reasons such as a preference for the look of the aging painting’s patina of an “old master” look such as a fine crackling or they simply prefer materials that have been in use for centuries rather than decades. There are so many sites offering extensive expert information about varnishing so I won’t go into detail with a discussion of specific types, brands and purposes here. I will show a Winsor & Newton and Gamblin you tube video on varnishing that discusses the basics, you may want to avert you gaze from the actual painting he’s varnishing but it does offer some helpful basic information. At the end of the article I’ll also provide a several links to site with specific information related to brands, types of varnishes as well as recipes, etc.

Right now I’m more interested to examine the less discussed case for not varnishing at all and how some important painters since the mid 19th century became adamantly opposed to varnishing, artists such as Cezanne, Monet, Cassatt, Pissarro among many others. Picasso and Braque were oppose to varnishing their paintings for a number of important reasons, primarily aesthetic. Monet and Pissarro abandoned the use of varnish on their work after 1880, but for different reasons: “Pissarro because of his desire for a matte finish; Monet lest it discolor his effects”

The painter and art historian Anthea Callen discusses the politics of varnish at length in a section in her The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity Sadly this amazing book is out of print but there are still used copies available for a price. Note: If you do buy this book please use this link to Amazon, by doing so will help support this site.

This book is perhaps the most comprehensive study of Impressionist techniques written. Her exhaustive research studies all aspects of Impressionist painting that are of great interest to painters who want to know more about the historical context of painting directly from nature. She also has a smaller but popular and still published book, Techniques of the Impressionists

from the publisher:

“Drawing on scientific studies of pigments and materials, artists’ treatises, colormens’ archives, and contemporary and modern accounts, Anthea Callen demonstrates how raw materials and paintings are profoundly interdependent. She analyzes the material constituents of oil painting and the complex processes of “making” entailed in all aspects of artistic production, discussing in particular oil painting methods for landscapists and the impact of plein air light on figure painting, studio practice, and display. Insisting that the meanings of paintings are constituted by and within the cultural matrices that produced them, Callen argues that the real “modernity” of the Impressionist enterprise lies in the painters’ material practices. Bold brushwork, unpolished, sketchy surfaces, and bright, “primitive” colors were combined with their subject matter—the effects of light, the individual sensation made visible—to establish the modern as visual.”

Here is an embedded version of the free google ebooks version of it, that has significant portions available for reading. Of particular note is the table of contents which is clickable and goes to a partial view of the chapter topic.

From Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity

“For the Impressionists, varnish was not applied automatically or arbitrarily to a painting. The physical and optical effects of varnish on the oil paint layer are immediate and irreversible. Not only is mattness replaced by an even, glossy skin but colours are enriched, appearing more saturated, and the paint layer is made more transparent. It also produces a darkening in tone, exaggerating light-dark contrasts, which is exacerbated with age as the varnish yellows, darkens and further distorts the paint layer colours. Varnish was intimately associated with the Academy, with academic practice and fini, and with the false ‘chic’ of the Paris Salons. Rejecting varnish was not just technically sensible, it actively subverted the reactionary ethos of the Academy. In addition to changing a painting’s physical appearance, varnish, and therefore the lack of it, carried an ideological message: the decision not to varnish signaled not only the work’s modernity, but that of the artist, too. A history of the debates around picture varnishing forms the context in which a more detailed analysis of Impressionist paintings can be located. Examining contemporary art criticism, treatises on technique, the opinions of dealers and artists, and the paintings themselves, a pattern of views emerges that gives new significance to the problem of varnish.” …

“The art of Italian painters before Raphael provided an exemplar at once practical and aesthetic to modern painters: newly discovered, the luminosity, chalky bright colour and shallow pictorial space of early Italian painting offered an alternative to the rich, patinated surfaces characteristic of official clair-obscur oil painting. There was, therefore, a politics of varnishing, of gloss versus matt effects – art practice, aesthetics and ideology are intimately linked.”

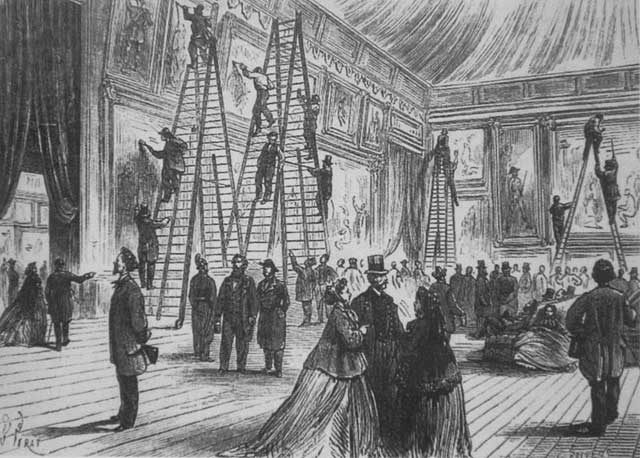

Vernissage,(Paris), 1866.

Interesting Wiki link on Vernissage

In marking the completion of paintings for display in the official Salon, vernissage was the rite of passage from private to public, from studio to gallery. The glazing of paintings was forbidden at the Salon; varnish, like the regulation gilt frames, was compulsory until the I880s, when the impact of avant-garde methods provoked a change in official practices. In the Academy’s view, varnishing imposed uniformity on the exhibition while simultaneously linking it to a tradition of ‘great art’ of the past – varnished paintings embodied the notion of dignity and nobility in grand art; the picture was set in aspic, embalmed. Varnish on painting, then, carries layers of meaning beyond the pragmatically physical. On both the literal and metaphoric levels, varnish imbues painting with a heightened clarity, unity and coherence. The varnish film seals in the matière of painting, unifies the surface, slicks over its rough edges, its visual inconsistencies, even intentional contradictions; glossing it over, varnish subdues the coarseness of matter and the animated, scattering luminosity characteristic of a rugged, matt surface. Varnish had a normative function: it made vanguard art look more like academic art. Sameness and uniformity were reassuring.

E. H. Gombrich, Dark Varnishes: Variations on a Theme from Pliny, The

Burlington Magazine, Feb., Vol. 104, No. 707, 1962, pp.51-55 [Trapp

no.1962G.1]

From E. H. Gombrich’s essay:

In 1638, Junius made the story available to English readers in his book on The Painting of the

Ancients:Apelles … who was wont to be very moderate in all things that concerned the Art, because he would not offend the eyes of the spectators with too much cheerefulnesse of gay and flourishing colours, did by an inimitable invention anoint his finished workes with such a thinne kinde of inke or vernish, that it did not onely breake and darken the clearnesse of the glaring colours, but it did likewise preserve them from dust and filth … [p.285]

In 1691, Filippo Baldinucci gave a lecture in the Accademia della Crusca on the subject of ancient and modern painting within the context of the quarrel between the Ancients and Moderns. One of the points in favour of the moderns was, for him, the invention of oil painting, and one of his arguments to

prove that the ancients lacked this technique was precisely Pliny’s story. His point is that this technique of toning down excessively luxuriant colours was precisely the one used by Italian Trecento painters who worked in tempera:… they spread a varnish over their panels which was a certain mixture that gave their pallid paintings a certain effect of greater depth and greater strength and, toning down the bright surface a little, brought it closer to natural appearance.. .

It might be argued that modern painters also use such varnish on their oil paintings, but I would reply that this usage, which only few adopt, does not serve to counteract any shortcomings of oil paintings as such, that is, to give depth to the darks and to tone down the lights more delicately, for oil painting does not stand in need of such aids. It is used rather to remedy some accidental mishap that sometimes occurs because of the priming, mastic or other, which is applied to the canvas, or that originates in the panel or canvas itself, that is, when it attracts the liquid of the oil so strongly that it almost draws it out of the colours and dries them up in some places to such an extent that this accident alters their appearance on the surface. It is then that by use of another fatty substance, that is, by means of the varnish applied where there is too little oil on the surface, one is able to bring out (and this is the salient point) what is already in the oil painting rather than something that is not there at all—which was precisely the effect that the varnish of Apelles achieved to some very small extent.[10] There is nothing in this description of the oil painters’ practice of bringing out a passage that had `sunk in’, which would refute Mr Ruhemann’s contentions. It merely shows how difficult it is to make a hard and fast division between paint and varnish

From a MOMA conservation article about varnishing and Pablo Picasso’s painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

“Paintings that have been varnished are also cleaned, or more accurately, devarnished, when the varnish discolors over time and thus distorts the original colors of the painting. Finally, some paintings should not have been varnished at all, and a varnish can compromise the essential aesthetic.” In this case, a painting that may be de-varnished, not to be re-varnished once the cleaning is finished, what steps do you take to help conserve the painting without using varnish?

The presence of the varnish on a painting, which the artist did not intend to be varnished, does not preserve the painting. Indeed it can do much to diminish the essential quality of the painting. To protect the surface of an unvarnished painting from dirt and grime there are, if necessary, a number of things we do. In some cases the paintings are framed with glass or Plexiglas to protect the surface. This not only provides a physical barrier from airborne grime but also provides a buffer against any climactic changes and (in the case of Plexiglas) protection from damaging UV light. In the case of a painting the size of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon we might decide to place a barrier in front of the work to prevent visitors from approaching too closely. Under these circumstances the only treatment necessary would be a routine dusting with a soft brush once a month or so.

Of course 19th and early 20th Century artist who avoided varnishing to preserve the matt appearance didn’t have the variety of modern synthetic varnishes that we have today. Unless the paintings is protected with a varnish layer or some other means it will collect dirt in the interstices, which can rarely if ever be removed without damaging the paint layer. Dusty, dirty paintings are likely to be particularly problematic in direct painting where impastoed brush marks makes for an uneven, irregular surface where cleaning would be more difficult.

Some painters in order to avoid using a varnish to preserve the matt surface and other reasons have opted for framing their oil paintings behind glass. I’ve read this practice has been particularly prevalent in Great Britain. With new picture glasses on the market such as Museum Glass and it’s anti-glare properties perhaps make this solution even more appealing if not for the high-cost. Especially for larger paintings where the weight of the glass also becomes a major factor.

In our post post-modern era, for better or worse, there no longer seem to be any hard and fast rules about techniques such as varnishing. Both abstract and representational painters may have many valid reasons for varnishing or not varnishing. My suggestion in this regard is to make sure your decision is based on the best solution for preserving the look of your work, not varnishing shouldn’t just be a rationalization to avoid the hassle or conversely you varnish just because you heard that is a rule you’re “supposed” to follow.

If you feel strongly about not having a varnish applied for aesthetic reasons then it’s suggested to write on the back of the painting – Do not varnish. Or if you do varnish you can also write when you last varnished and with what type – which will be helpful to anyone in the future wishing to remove and reapply varnish.

Ultimately it is imperative to remember the obvious, but often overlooked, concern that will protect the painting and enhance longevity more than any varnish might offer, is that you make your painting strong enough visually so that people will want to care for it long after you’re gone and to avoid the painting’s death by dumpster.

Comprehensive resource on all things related to varnishing oil paintings from Amien (The Art Materials Information and Education Network) Varnish Forum topics from Amien

Basic info on varnishing from Winsor & Newton

fairly good video from Dick Blick about varnishing but the soundtrack is a little grating!

Video from Gamblin discussing the application of Gamvar and cold-wax medium. (I prefer to use Gamvar when varnishing and I also like the use of the cold-wax medium for a more matt sheen.)

Conservation Wiki article on varnishing

Good article at Spaces Between the Gaps article on Varnishing

Larry thanks you so much for this informative new section “Sounding Technical”. Varnish is a subject that I have been rethinking recently. In my early 60’s art school, color field painting, years varnish was not on the menu. Subsequently, as an art conservator, I began to appreciate the range of pros and cons to the use of varnish. Only in the last ten or so years have I varnished my own work but I am not resolved on this matter. However, I do not think a well done, good painting, is made better by the “unifying” aspect of varnishing. On the other hand, for some the varnish is an integral part of the intended outcome, the final result of a well done work. I now believe that, although varnish can be a crutch, it is really a personal choice of aesthetic and of technique.

Your article, Larry, was thought provoking, informative, and timely. Thank you.

Mamie Walters

Hey Larry,

Nicely researched article. I think that for most contemporary artists that sell work, it’s a matter of time rather than a considered decision. The work is rarely finished 6 months in advance so one can’t really put the varnish on. A friend recently delivered a wet painting to his dealer in order to have it in his show. Hard to varnish that. I love that you put the horse in front of the cart by saying make good work first. The rest will sort itself. Thanks again

Thank you for this informative article. I was particularly interested in the “oiling out” process which can be used instead of varnish. I happen to dislike to glossy look of varnish on an oil painting–any painting–but I’ve found that oiling out can actually be used instead of varnish. I wonder if the impressionists, who disliked varnish, used a version of oiling out. The book you refer to, The Art of Impressionism, doesn’t mention this. This book, by the way, is one of my most pr4ecious possessions. I’ve had it since it first came out over ten years ago, and I wouldn’t give it up for anything. Not even for the current price–over $500 on Amazon the last time I checked.

Thanks Joan, Mamie, and Neil for your comments about my new Varnishing article. I learned a lot through the research so hopefully this will be helpful to someone else too. I wish I had the problem of either selling or showing my work so quickly that I never get the chance to varnish but if I did have that problem then I would either suggest to the buyer to return to me in 6 months for varnishing or apply some retouch varnish (which can be applied when the painting is dry to touch as I understand it) Oiling out from what I’ve heard isn’t a very good substitute for varnishing as it will be harder to clean the painting when the time comes years later. Also while it may make the painting look better initially, give a uniform sheen and the like – I don’t think it will offer much protection to the paint surface. One last reply to Joan – The Art of Impressionism book is currently at 164.94 for the lowest price as a used book on Amazon. I may get this for myself this Christmas.

Varnishing = yuck, in my view. Paintings are made out of paint and paint is what I like to see, not shiny gloop. While I can understand a conservational case for it, as described in this very informative article, The Old Masters understood varnishes and expected their work to be varnished, so for Old Master paintings its okay but from Manet onwards most artists have been opposed to it. Certainly no modern paintings should ever be varnished. Soap and water will do for surface dirt (or spit, human spit; that works well too).

The absolute worst examples of varnish abuse I’ve ever seen are at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. All their Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings are (a) stuck into ornate fake Rococo frames, (b) hung in strong artificial light and (c) absolutely slimy with varnish.

They gleam, they shimmer, they shine; they look nothing like how the artists intended them to look. The paintings look like reproductions of themselves. In the Van Goghs the varnish on his ridges of impasto make irritating little points of light that bounce back at you and distort your viewing.

All the Barbizon School paintings, the Corots and Millets, are not only varnished but they’re glazed as well. The MFA says this is all to do with curation and preservation, I say its vandalism. Memo to curators: did the artist stick this picture in an elaborate golden frame and put glass over it? Did the artist slather it with shiny varnish? If the answer is no, then it should not be done –ever – because you, museum person, don’t know what the artist intended better than the artist did.

I’m at a loss to recall the exact passages, but I found quite a lot of technical, conservation material in “Modern Paints Uncovered: A Symposium Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute, Tate, and the National Gallery of Art.”

One issue that the conservators discuss is that not all varnishes stay soluble indefinitely, which is a problem because even the best varnished paintings will likely need a cleaning/revarnishing every 50-100 years. Many of the modern, petroleum-based varnishes seem to become difficult if not impossible to remove with solvents after several decades. Dammar varnish, interestingly, has a reputation of staying soluble to turpentine for centuries, which is a good thing as dammar yellows more easily than most modern varnishes. Quite a few Rembrandt paintings that had nearly been lost under dirty dammar varnish for centuries are now cleaned, revarnished and looking brand new.

Another issue was that it may actually be more critical for acrylic paintings to be varnished than oil paintings. The microscopic surface of acrylic films have similarities with that of a sponge, which makes it very easy for dirt and grime to attach. Oil films are much smoother as well as harder and more resistant to scratching than acrylic. Ironically, because acrylic is inherently more “modern,” it seems fewer acrylic painters varnish than oil painters.

Also, conservators really get anxious about cleaning the varnish off a painting that has passages of thin glazing on the final layer (it is possible to accidentally take the glaze off with the varnish). Alla prima painting (what I’ll call “juicy” painting without getting overly impasto) is much more durable under such cleanings.

I personally try to dammar varnish my paintings after a year (and label the backs of the painting with technical information). I use a lot of coldpress linseed in my paints and I have noticed that my paint films seem to dry much more matte (dark colors really lose their saturation and value) than when before I used coldpress linseed. I also “oil in” often, which can lead to weird splotchy surfaces if I don’t oil in the whole painting each session. A thin coat of dammar varnish has really helped fix these problems for me without creating the super-glossy surfaces everyone associates with salon paintings.

Thank you Brian Kelley for your informative and interesting comment. I find it curious that there seems to be such a difference in opinion by the many experts. I’ve often read where modern synthetic varnishes are supposed to be preferred as they are much easier to remove with little or no risk to the underlying painting – now I hear this may be all wrong! I have also read that dammar varnish could possibly bind with the glaze medium or medium with dammar in it and risk removing the paint layer along with the varnish when it’s removed. I am curious to read about good modern alternatives to the slick, salon-style varnishes. I should think the more matte varnishes which use wax might be a good way to go but I’d like to research even more. Here is a link to some general information about this symposium. When I get a chance I’ll look into seeing if I can get the complete text (a publication is available).

A follow up:

Thanks Larry for your response. Regarding using dammar in artist mediums and varnishes, yes this could be problematic, especially as the medium is probably used partly because of its good glazing properties, meaning it will be in thin films directly below the varnish layer. Also, dammar is VERY brittle. For a single, thin coat of dammar varnish, this brittleness is not too bad, but something like alla prima painting with dammar in the medium is inherent vice.

For those painters who don’t mind getting a little into chemistry, there are some interesting small conservation articles on varnishes here at Conservation Online:

http://cool.conservation-us.org/waac/wn/wn17/wn17-1/wn17-107.html

These conservators make a big emphasis not just on natural vs. synthetic varnishes but also whether the varnish has a high or low molecular weight. Higher molecular weight varnishes are *usually* synthetic and have a lower refractive index, making them more matte. Varnishes like dammar have a low molecular index (and a higher refractive index > glossy). The problem is that high molecular weight varnishes can crosslink with paint films and can become increasingly insoluble. The worst of these are methacrylates (aka acrylic varnishes) which display reduced solubility after ten years. PVA, polyvinyl acetate, another matte varnish, does not appear to have this problem and may be a better synthetic alternative. Incidentally, PVA is often used for sizing paintings (a synthetic substitute to rabbit skin glue). Also, conservators note that high molecular weight varnishes are trickier (thicker and quicker to dry) to coat and tend to attract more dust, but that may be the price to pay if you want to avoid a glossy surface.

There is also discussion on UV filtering agents, especially a class of chemicals called Tinuvin. It seems that very small additions of these agents into the dissolved varnish can exponentially expand the life of the varnish, protecting the painting from fading, the varnish from yellowing and potentially from becoming more brittle (though, like all varnishes, it will do little to prevent oxidation). The exact form of tinuvin, percentage of tinuvin to varnish resin, type of varnish resin used and thickness of the varnish coat (by the nanometer) all have complex interactions, only improving the varnish when the formula is *just* right.

The more I read about synthetic varnishes the more I think they are likely superior to natural varnishes when done right. The problem is “right” could be a very specific chemical formulation and application method that requires significant research and testing. For someone who wants a low-tech varnish that is more forgiving, I still think dammar is a decent choice. As long as you wait a year and a apply a single coat with a big, soft brush while the painting is flat on the floor in a clean room you (or someone else whom you trust, should you no longer have possession of the painting) can’t really mess it up. Leave the synthetic varnishes to conservators and truly scientific painters (Old Master alchemy isn’t very helpful here).

I’m curious if anyone here is using Golden Paints varnishes or GAC Acrylic Specialty Polymers as a varnish. If I was to quit dammar for synthetics, I’d probably start my search there. I would also note that Golden’s website have very thorough technical notes on these products as well a section of research articles that have recently been focused on the issues of using acrylic chemicals (sizings, primers, varnishes) in conjunction with oils and traditional oil painting methods.

So, to varnish an acrylic painting with temporary varnish I would need a coat of something else first, so that later on I would be able to safely remove/clean the varnish. Which exact material is this coating/brand? Thank you.

Vielsa,

Thank you for this article and the interesting discussion. I have to admit that since my training and disposition tends toward the modernist, varnishing has not been on my radar for my own work. However, I have recently done interviews with students from a conservation training program and many of their questions are around this issue. In thinking through my answers it became apparent that the question of varnishing or not is as much ideological as it is technical.

I think that the technical aspects of building paintings have real implications for the meanings that paintings produce. One of the best “art history” books that I’ve read recently was “Willem de Kooning: the artist’s materials” by Susan F. Lake, under the auspices of the Getty Conservation Institute. Her rigorous analysis of the materials and techniques of de Kooning’s practice held very interesting insights into his aesthetic of constant adjustment and metamorphosis on the surface of the painting. Another catalogue that integrates conservation/scientific insight is “Matisse: Radical Invention,1913-1917” by John Elderfield and Stephanie D’Alessandro.

On a practical note, I would echo Brian Kelly in recommending the Golden Paints site for info on synthetic varnishes, the articles are very informative.

You can prevent the problem of having shiny and dull areas, by adding a little bit of very fine marbledust to your mix.

But what he does in the oiling out video is good practise. You can also use linseedoil for that. That gives a lovely satin shine, and doesn’t darken or yellow if you don’t use too much.

JP

I have a very small painting — maybe 4″ x 4″ Given to me by an old friend who died about 10 years ago — I think he had the painting for maybe 30 years — and he was a very heavy smoker. The painting was very dark when I first got it — and that has continued — Any suggestions – how I might clean this painting. (It’s a portrait — and it does look like it was varnished.

Thanks — Peacockjp@aol.com

Hi!

Question: I have used a glazing medium (Liquitex) in my oil painting on the last layer and I find it is too shiny now. The subject (a horse) has the glazing on it, the background doesn’t.

Will a mat varnish get rid of the shiny glazing on the horse and make the background and the subject the same matt texture?

I really appreciate it if you could get back to me, because I don;t know what to do and the painting was a commission for a client so I don;t want to mess it up! And any ideas on what kind of varnish I can use?

Thanks!

greetings from the Netherlands!

Ida