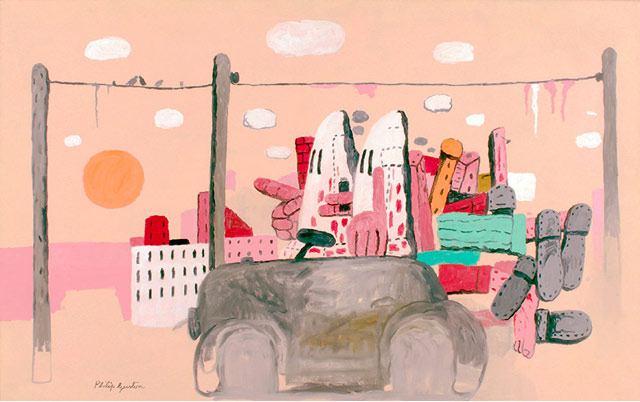

Philip Guston The Canvas, 1973 oil on canvas 67 x 79 inches (from McKee Gallery – larger image available)

Guest Review by Thaddeus Radell

Philip Guston (1913-1980) is heralded today as an icon of pure painting. This fact is all the more poignant, as by 1970 he was actively scorned by critics and most artists as an iconoclast defying the New York School.

In that last remarkable and reclusive decade of his life Guston insisted on a more direct visual communication with the viewer that prompted his return to figuration. Powerful, poetically charged images emerged from milling ideas and memories together with quotidian observation of objects that ceaselessly surrounded him: books, clocks, paint, canvases, boots, cigarettes.

As Maurice Denis remarked, ‘We should remember that a picture…is essentially a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a particular pattern.’ And so Guston harnessed a dense and sumptuous Courbet-esque language of paint into equally dense and sumptuous imagery that continues to entrance, disturb and delight the contemporary viewer. In the end, sequestered in his Woodstock studio, mindful of, but not in any way bowed, by popular opinion, Guston simply did, and did extremely well, what painters do: paint.

The Philip Guston exhibition now on view at the David McKee Gallery is an inspiring, if problematic, offering from one of the most pictorially demanding and ‘image-ridden’ painters of the second half of the last century. The current exhibition marks the centennial of his birth and seemingly celebrates the artist’s rebirth into figuration. All of the works, except the impressive The Year (1964), date from the late period during which Guston began to draw and paint single objects in a highly condensed manner. His boldly colored figurative narratives are solidly removed from the subtle tonal resonances established in his mid-career abstractions. The Year remains a resilient and potent statement of Guston’s ability to address key issues of the New York School while enigmatically retaining and nourishing a commitment to simple, massive forms that are, quite obviously, figuration.

The exhibition, however, chooses to focus, (and rightly so this viewer believes), on that last decade or so of the artist’s life. These, and not the tonal studies in abstraction, are what define Guston as pictorially demanding. The painting chosen to welcome the visitor into the Centennial is Dawn, from 1970. Exquisitely, deceptively, warm and delightful in terms of color, Dawn is actively rife with Guston’s dark symbolism of Klansmen, severed legs, industry and nails. Together, the color and the content cement the image into a painting of top quality. And the splendid invention of the scumbled grey car! Sadly, therein lies the first tremor of fallibility in simple visual cohesiveness and dynamics that, not infrequently, plagues this exhibition. Are the Klansmen actually supposed to be driving the car? Every other shape and form, no matter how abstractly conceived, has an appropriate and specific space and light relative to everything else in the picture. The car, however, wonderful and exuberant in itself, fails to establish a credible space. Was that the point? The discrepancy between the two? Taken separately, the car is a wonder of understatement and the Klansmen are of a darkly lighthearted clarity that only Guston could achieve. Yet the gravity of this pictorial stumbling is only magnified by its dominant position and, in the end, disappoints.

Philip Guston Dawn, 1970 oil on canvas 67 x 108 inches (from McKee Gallery – larger image available)

The exhibition has been hung with great care and refinement and continues to eloquently alter smaller scale works with such monuments as To J.S. (1977) and Discipline (1976). To J.S. is a superlative work, one that clearly defines Guston as remarkable painter. Here, not only is the content of the picture compelling and haunting in the broad context of our shared social consciousness, but the soundness of its construction has echoes of the great Henri Rousseau. Every form issues from an inscrutable and unnerving precision of weight and position. This necessity of form is further heightened by what James Elkins describes as the alchemy of painting, that state of hypostasis, where ‘one has the feeling that something as dead as paint might be deeply alive’ (Elkins, What Painting Is), the transformation of paint into a higher, spiritual substance. A few feet away, Discipline, on the contrary, stands alongside To J.S.’s profound skill and soulfulness as an embarrassing younger brother. Painted a year prior, the marching legs, those wonderfully nuanced, ubiquitous tones of Guston red, are now enslaved and, quite literally, beaten. The over-statement of fist, club and dripping blood is devastating to the overall integrity of the picture. The solemn march of limbs against a Spanish black would have thrilled with suggestion and left the viewer visually nourished, overwhelmed and disturbed. Bergman as opposed to Tarantino.

On the opposite side of the gallery are hung three major works that decidedly reinforce these disturbing, yet humanly problematic inconsistencies. Waking Up (1975), while perhaps not quite as visually succinct as the Met’s Stationary Figure (1973), is a striking example of Guston’s masterful ability to comprehensively orchestrate shapes into a haunting image. The energy that arcades back and forth across the canvas from the staring eye and drooping cigarette to the last set of upturned boots and the feet that brake against the far edge of the canvas is hypnotic. Everything, from the red sea pressing the figure into the bed to the chalky nightmare visions that animate the living black space that dawns around the head, is finely crafted and felt.

Waking Up is braced between Alfie in Small Town (1979) and The Canvas (1973), two works that aggressively dispute Guston’s legacy. Canvas argues for the bold, well-staged visionary impact that represents the artist’s main strengths, if in, perhaps, an overly reductive context. Here again is testimony of an extraordinary sense of design. The almost impossible balance of damp grey bricks that support the weight of the hefty rose of a one-eyed canvas, framed by a settled black shadow and against a bed of pallid, luminous grey is simple, austere and powerful. Alfie in Small Town, on the contrary, though absolutely luscious in terms of clear and well-staged tones of color, comes off as being so silly that it is truly difficult to look at. Swallowing the reference to comics is no anecdote to such heartless and condescending image-making.

Philip Guston To J.S., 1977 oil on canvas 68 x 104 inches (from McKee Gallery – larger image available)

In the smaller room at the rear of the gallery are several truly wonderful smaller works in delightful dialogue. Unfortunately dominated by the far less interesting Musa (1975), whose clumsy compositional simplicity over-rides the potential of its content, these works further testify to Guston as able colorist. Of particular vibrancy is Untitled (1979) and it is interesting to note how a small-ish painting (48 x 42”) of impeccable, unusual color harmonies and defiant compositional impact can outflank a much larger and domineering format such as Musa. In Untitled, the accordion-like pummeling of the central green is remarkably, inexplicably grounded by a black shadow over a sickly pale and fascinatingly acid green sea. More conservative coloristically as a picture, Forms on Rock Ledge (1979) offers a classic Guston muddling of symbols and forms that in a lesser painter’s hands might simply constitute visual inarticulateness. However, Guston can be adept with instilling an essentially complacent, centralized composition with force and enigma. Here he dispels any queries into possible pictorial complacency by the insertion an intelligent and very odd and unexpected horizontal form in the upper right quadrant.

The exhibition also harbors a host of smaller works on paper or panel, in charcoal, acrylic, gouache and oil. There are several visually stunning works, such as Untitled 1980, a profoundly rich acrylic on paper whose simplicity is majestic. Several duets are offered, such as Shoes (1972) and Untitled (Shoe) 1968 as well as Book (1968) and Untitled (Book) 1968. Here again, there is a dissonance that is somewhat disconcerting. The sheer quest of the starkly isolated form within the format exalts the image in Book, whereas its counterpart, Untitled (Book) is too insistent, too reduced a form to truly hold and engage the viewer. Likewise, the plurality of forms and complexity of construction of Shoes renders the forthright Untitled (Shoe) weak and uninspired by comparison.

A century after his birth, Guston does remain, assuredly, a major player in the history of American painting. His harnessing of a troubled past into a coherent and poignant body of work is poetry itself. Stumble he does, yet he endures as a full-throated assertion of the inherent dignity and acute relevance of the painted image.

Philip Guston Waking Up, 1975 oil on canvas 67 x 129 inches(from McKee Gallery – larger image available)

The current exhibition at David McKee Gallery continues through April 20th.

(editor note: Painting Perceptions would like to thank Thaddeus Radell for his generosity in sharing this review. Thaddeus Radell is a painter and sculptor living in NYC. More information can be found on his website.

I used to love those late Gustons; now I’m not so sure. Too literal, too narrative, too easy on the audience, maybe. I know why he felt he had to make them but nowadays I prefer the abstractions; the way the pictures seem to be making and unmaking themselves before your eyes,the paint smooshed and dragged over the surface, their weirdness and slowness and the sense of time arrested. The greyer and gloomier they are, the better I like ’em.

This is definitely one of those shows that I wish I were in NYC to see…and also very interesting to see here on this blog, Larry. Like Richard, I’m not really sure what to make of Guston (the late work, that is). He’s definitely revered by some many artists I admire, and I can definitely see the influence on contemporary painters like Amy Sillman, Dana Schutz, Barry McGee, etc…I’ve only seen a few in person, and from what I remember that’s the way you need to see them; the scale, the paint handling, even the smell of the linseed oil. I admire these paintings for the courage it took to make them, in the face of what I can imagine was a very vocal public rejection from the ‘Art World’ and his friends. Well, that’s my 2 cents….thanks for the review

That’s a good point, Francis. Context matters. When I first saw these paintings you could still smell them; they seemed really vivid and real and honest in a way that a lot of the art of the 70s didn’t. I mean, put a Guston next to, say, a Warhol and I know which one I’d pick. But put a Guston next to a Braque or a Balthus or a Milton Resnick and the choice gets a lot harder.

Well, well, well, I’d think putting anything next to a Warhol, and I mean anything, a pencil for example, you’d imagine anyone would choose anything over a Warhol? But I suppose it doesn’t work like that, all though I’d certainly choose the pencil over both Warhol and Guston! Suppose nobody picks any of it? Suppose everyone is totally let down; complete intellectually bankruptcy? Guston’s handling of paint, what does that mean? Look to your left and notice that someone is lacking in understanding and look to your right and see someone swimming in the waters of life (what you assume the difference to be), and where does it put you knowing your perception is lacking? How come when I look at a Warhol I’m reminded of bologna, and when I look at a Guston I’m reminded of barf? Guston’s handling of paint is not enough; the way paint is handled regardless in anyone’s work is not enough. Why does “paint handing” always pop up in the unspoken baby boomers litmus test of artistic authenticity? Also, a Warhol and a Guston together really makes me feel nauseous. I’d like to have the pencil again please, so I can stab my eyes out, plunge it deep into my cranium reaching that place that needs to be scratched and forget it all together, both Warhol and Guston. And that’s my fake, imaginary, fractional reserve two cents penciled in out of thin air.

There are really three Guston stages: the first, during the 30s were representational, pretty tight and well constructed social comment works; the second period was during the 50’s and early 60s and was his haunting Abstract Expressionist period; and the last, as shown here and discussed,

the period called Expressionist. Me? I have always loved his AbEx period with their passages of

paint, color, and implied movement as one of pure beauty, the soul of a painter working in the

zone. You would have to see them to really appreciate their timeless imagery, sense of nostalgia,

and romanticism. Guess those are now long forgotten qualities for many, but not for me and other painters still looking at that era. Warhol’s cynicism and consumerism are not in the same league IMO; not even close.

Guston became known for his lyrical abstractions in the 1950’s. His version of abstract expressionism was poetic compared to the aggression in Kline and DeKooning (Motherwell being somewhere in between). His decision to walk away from his acceptance as a major figure in abstract expressionism is seen by many as a heroic act. Within the context of contemporary art history where there was so much critical bias against figuration I would have to agree that it was indeed heroic. Long after the pendulum has swung back to an acceptance and desire for figuration in art, I believe what strikes us today as so difficult to accept about Guston is the brutality of his drawing. It is as if any sort of “paint handling” prowess is purposefully negated by the rawness of the graphic marks. They are clumsy and awkward and I believe intentionally so. These paintings are meant to be hard to like.

The art world in the early 21st century is a diverse world with competing interests for conceptual, performance, realist agendas. Thank God for that! We are not asked to like or condone everything that is graced with the label of “art”, but an open mind to the realm of possibilities keeps us from being isolated in small dogmatic tribes.

I’m not sure I agree that Guston’s drawing is brutal or clumsy, Christopher. I think its very knowing and self aware; it looks rough and gruff but its done by someone who can do better, who is a professional fine artist (although Guston was self taught) not an amateur or a child or an outsider. That’s why the pictures hold our atention the way they do. The artist Guston most reminds me of is Dubuffet; they might make ‘raw art’ but its always very well cooked and beautifully presented, made with only the finest ingredients.

Hi Richard,

Point taken. I did not mean to assign him to an outsider aesthetic; perhaps my own use of the word “brutal” was the clumsy part! Dubuffet is an interesting comparison. When Dubuffet is truly “raw” I most heartily agree. Dubuffet can appear decorative at times and that can never be assigned to the later work of Guston. Interesting discussion.

Maybe Guston was one of the last examples of the modernist theme that the more seemingly untutored, primitive or non-Western looking something is, the more authentic it becomes. The Neo-Expressionists of the 1980s finally ran that notion into the ground with their nonsense. In historical terms you can see why the craving for the primitive arose and why it was necessary for artists a hundred years ago to explore those possibilities. Nowadays though, it seems a little peculiar; like hearing the Berlin Philharmonic playing Ramones songs (not that that wouldn’t be something!)and that’s why I look at those late Gutons and go “hmmmm…not sure”.

I don’t agree that the car in Dawn disappoints. Formally, it introduces a tension by firmly stating the horizontal against the verticals of the poles ( remember Pollock’s Blue Poles?). It also introduces a tension with he rest of the elements in the picture which are all clearly drawn, whereas it looks ( only looks…) unfinished, just as the tiny birds on the electric wires echo it in their ” unfinishedness”. Literally framed by the rest of the picture looks like a classic painting in the painting, as a real statement of PG’s gift as a painter because it is a piece of pure painting. The whole picture revolves around it. There was another Klan painting on panel in the show, all in black, white and gray, tat I found very impressive, titled “Plotters”, which deserved a mention here.