Interview by Elana Hagler

Elise Schweitzer’s full-bodied, bold, and luscious paintings caught my eye a couple of years ago and I’ve been following her work since. Elise has a wonderful mix of formal invention and playful, curious narrative in her work. Many painters I’ve seen tend to fall into the formalist camp or the narrative camp, and one of the things that I very much appreciate about Elise’s work is that she plays within both worlds and does so with confidence and a sense of visual adventure. She is deeply committed to the color relationships and shape life of a painting as well as to that art of storytelling that links her work to those poets of paintings past.

Elise Schweitzer received her MFA in Painting at Indiana University Bloomington in 2009 and her BFA from University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 2006. She has taught as an adjunct instructor at Herron School of Art in Indianapolis, and in the fall of 2013 she will begin teaching at Hollins University in Virginia as an assistant professor of painting and drawing.

A recent show of her artwork at Gallery 924 in Indianapolis featured giant figurative paintings of skydivers, centaurs and belly dancers. You can learn more about Elise and her artwork at EASchweitzer.com.

EH: It’s great to have you here, Elise! I would love to hear a bit about your background and when painting became the obvious path for you. Was the choice of going into art something that seemed relatively obvious or was there any internal or external struggle?

ES: I am extremely fortunate to have an extended family who always supported my interests in art. When my dad was an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis he became friends with a wonderful painting professor named Fred Conway. My dad went on to become a lawyer, and over the years they bartered and exchanged legal work for artwork, and as a result we had a number of large, beautiful oil paintings and watercolors around the house. Every now and then we’d move the paintings around as my mom redecorated, so these fantastic paintings were just part of the background of my childhood. I never met Fred Conway myself, but I grew up with this crazy notion that art was a legitimate thing to do as a career.

Like everyone else I always struggled internally about this “career choice,” but that seems to have settled down recently. I think it happened when I was a couple years out of graduate school and realized I was, in fact, still making paintings. Being an artist was no longer something that I was aspiring to. It was happening in the present.

EH: I remember the dean of my grad school at one point told us to look around the room and that only one out of ten of us would still be painting five years from now. Five years from graduation would have been one year ago. At this point, there’s definitely more than 10% of us still painting…I’ll take that as a good sign!

Who are the people with whom you studied who made the greatest impact on you as a painter? What areas of exploration did each one emphasize for you or guide you in?

ES: I feel fantastically rich in the artists and instructors I’ve been able to learn from. At one point I counted sixteen different painting instructors from PAFA alone. I learned amazing things in drawing from Reneé Foulks and Al Gury. Drawing finally connected with painting when I had Scott Noel as a painting teacher. Scott has clearly influenced an entire generation of painters through his complete devotion to the intrinsic beauty of shape and color. I’ve been fortunate to stay in contact with him through the hand-written, snail-mailed word, since he does not “do” email.

In my last year at PAFA, Eve Mansdorf visited and did a slideshow of her massive figurative paintings, and I immediately knew that I wanted to study with her at Indiana University’s MFA program. Her outsized ambition and incredible sense of color were valuable enough, but her blunt honesty was an unexpected benefit as well. I really struggled in my first year of graduate school. I remember talking about it with her when she visited my studio. We were running through all the problems I was having, and she finally asked “Well what do you think you’re good at in painting?” I said, “I think I’m pretty good at making compositions.” She laughed out loud and said, “Really? You’re not.”

Hearing that made me sit up and pay attention. My compositions were, yes, really quite bad at that point. I paid much more attention to them, and found more meaning in them, and they got better.

EH: I’ve always been so curious about what it would be like to study with Eve Mansdorf. I’ve met her only one time, when we were standing cheek to cheek staring at an Antonio López García drawing at his retrospective in 2008 at the MFA in Boston. I remember that we were chatting for a while before we introduced ourselves, and when she said her name was Eve I knew it couldn’t possibly be any other Eve.

What sort of things did you learn about composition that took your painting to that next level? Inquiring minds want to know!

ES: I can’t say that what Scott and Eve intended to teach me about composition was radically different, but I can describe what I was ready to learn at the time that I studied with them. What really sunk in with Scott was seeing paintings as a series of interlocking two-dimensional shapes of tone. At the time that was revelatory, and it still is, but I think it led to a kind of frieze-like quality in my paintings. Everything was flat to the picture plane, happening in a shallow space, and hardly anything overlapping. Eve Mansdorf challenged me to look at how spaces go back, and twist around, and create complexity in the depths of that “box of air” of a painting. There’s that wonderful irresolvable tension between those two ideas. I didn’t appreciate that at PAFA, and I wasn’t able to deliberately engage that tension until graduate school.

EH: One of the first things I noticed about your paintings was the strong thread of narrative running through them. Dramatic storytelling seems to be as important to your work as are the formal issues…and to my eye, form and narrative are beautifully interwoven in many of your larger paintings. Could you tell me a little about the role of narrative and drama in your work?

ES: The narratives in my paintings are a scaffolding; they create a structure of formal problems to be solved. If a herd of centaurs charge in from the right, what kind of slingshot movement is going to carry you across the canvas? The most important part of that painting became the white plastic lawn chair falling over in the middle right. It’s a turnstile, catching the tablecloth, about to be kicked away by the centaur, spinning as woman in pink stumbles away.

That’s how the narrative ideas appear at first to me, but I’ve always discovered in retrospect or as I’m working on them that there is an autobiographical component to the imagery as well. As much as the centaur painting is an excuse to paint a battle scene, it was also a reflection of my mental state at the time. I worked on this painting for about two years, and the whole time I was also planning my wedding. The painting became a cathartic worst-case-scenario: no matter what went wrong, this particular disaster would not happen. It was also a reflection of a half-memory of the Battle of the Centaurs and the Lapiths, also a story about a wedding. At PAFA there are plaster casts of the metopes from the Parthenon depicting men and centaurs locked in battle, with plenty of beautiful drapery. I would have seen those friezes at PAFA almost every day, but I didn’t make that connection in the painting until I was almost done with it.

My skydiver paintings started with a desire to paint the cycle of movement you see in baroque religious paintings; a figure and fabric spilling down from a cross (or a tree,) a body being propped up, a crisis like a central well of gravity pulling everyone together. It’s also about that “safety orange” color, so intense that it makes skin seem green and violet. The more personal narrative is about how people react when family members go through terrible health problems. No particular character is a self-portrait, or maybe every character is a self-portrait. Sometimes I’ve felt like a martyr, sometimes I’ve felt like a good first-responder, and sometimes I feel like the guy in the corner who’s more upset about dropping his beer and peeved at the poor soul who just fell out of the sky.

EH: It’s like what they say about dreams: every character is really some version of you, however outlandish it may seem. What you say about the centaur-interrupted picnic vis-à-vis your wedding makes me think of the appeal of zombie movies. It’s putting a good chunk of the angst and turmoil we experience in real life into an impossible context, so that we can have some kind of emotional catharsis in a “safe” space. That certainly makes sense to me in terms of painting. I feel like we’re constantly sticking all of our problems as well as our desires, joys, and aspirations onto that canvas, because it’s so much easier (if still not easy by a long shot) to come to some sort of resolution in paint rather than in life.

On your website, I noticed many intricate and energetic studies for your larger paintings. What is your process of constructing a painting?

ES: The centaur painting took two years to complete, which was fun but ridiculous. I started that painting with only a vague idea of where it was going. At the time I could not figure out how to plan out such a large painting. I made a number of small compositional sketches, but no matter what, a small drawing or color sketch just does not translate to a twelve foot wide canvas. As I was going I would make drawings of particular figures, but I could never anticipate what kind of formal movement would make sense at such a large scale until I was in the middle of the actual painting, and that resulted in months of revisions. I think nearly every figure in the painting just about broke my heart; I repainted them so many times.

I found a partial solution with the large Skydiver Landing painting. Knowing that my weakness is always my “background,” I started with a broad painting of my backyard on the canvas, with no figures. Then I made a number of charcoal drawings of figures, trying to assemble a catalogue of gestures and poses, and then I photographed everything and cleverly composed them on top of the background image in Photoshop.

Something about a digital image seemed formally disconnected from that issue of scale. I could cut and paste the drawings, change their size, their orientation and levels of contrast, and print out versions as I went. When I went back to my paintings I still worked with models, outside in the backyard, but I taped my printouts to the side of the house behind me. Two of my models took five of the poses in the painting, so I could never actually see the whole complete tableau at once. I glanced at the printout every now and then, and it helped me keep figures in proportion and in relation to each other, and I still experienced the joy of unexpected shape relationships and connections. I was able to resolve the painting in a matter of months rather than years.

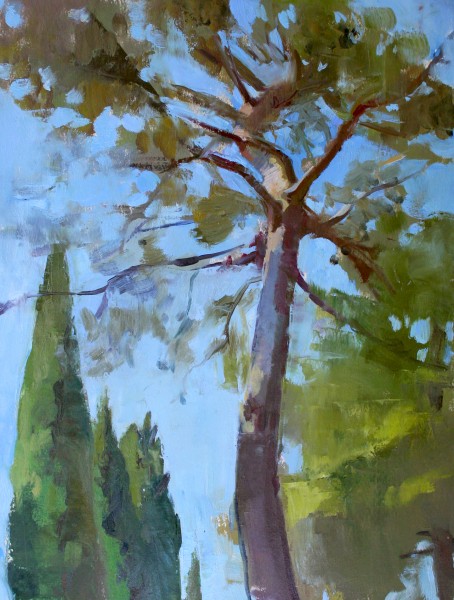

EH: I know that you just spent some time in Italy painting the landscape. I’m glad to be able to include some of these new paintings in this article. Is the experience of painting landscape alla prima very different for you than your more sustained multi-figure explorations?

ES: Yes, in June I took a small group of students to the International School of Painting and Drawing in Umbria, and it was a fantastic experience. Before this summer I had only spent a day or two at a time focusing on landscape painting, and although I enjoyed it, it didn’t seem connected to the larger projects that I worked on. Having two weeks to focus on landscape painting really changed that; or maybe it was just the Italian landscape. There are way too many fields in the valleys in Umbria, there’s no way you can include them all in a painting. It takes a will to organize that’s much closer to the way I make my large paintings than any other landscape I’ve painted.

In both the alla prima landscapes and the large narrative paintings, everything is painted directly, without underpaintings or drawings. The painting session feels the same, but the landscape paintings are only one session, while the large figurative paintings can go on forever. I did work on one larger landscape painting in Italy over four or five afternoons, and it felt like going down the rabbit hole. There were always more fields and more distant mountains, and I swear the crops were growing and changing colors as I painted them.

Last summer I started taking pictures of my large paintings after each day of work, partially to track how they developed, but also to count how many painting sessions it took to finish the painting; at the time I really had no idea. Twenty seems to be the magic number. After twenty sessions, each five or six hours, the painting feels like it snaps together. Each figure and each section of the painting might be fully painted and repainted at different points during those sessions, but getting the whole thing to work together takes that long. I also think the forms in the painting become more significant and meaningful through that repetition; someone’s elbow isn’t just any elbow, it’s the elbow that needs to be right there in that painting to hold everything together.

EH: I see a clear kinship between your large paintings and the Idylls of Lennart Anderson, who of course was Eve Mansdorf’s teacher back in Brooklyn. The “box of air” that you mentioned earlier as something that Eve would talk about comes straight from Lennart. When I studied with him in Montecastello, he would often talk about viewing a painting as a “box of light and air.” That saying stuck with me; it’s something I try to go for in my own work. It’s also something that I see very clearly in yours.

What painters, other than those with whom you personally studied, do you look at the most for inspiration?

ES: I wish I could see the Idylls in person! My strongest reaction to seeing those paintings in reproduction was “wait, we can do that?!” I love that those paintings are aligned so closely to the paintings that Lennart Anderson must love. It felt like they gave me permission to closely follow my own appetite. If I can’t get enough of Titian’s “Bacchus and Ariadne,” heck with it, I’ll make my own version.

I’m a big fan of Edouard Manet, especially his awkward early paintings where he also seems to be quoting Titian, and Giorgione, and Velasquez. I also love Joaquin Sorolla, he was known for painting giant canvases outside in the heat of southern Spain. I read that his contemporaries compared him to a lizard. I try to remember that when it’s brutally hot in my backyard and I’m trying to paint the foliage.

I enjoy the scale and complexity of Neo Rausch’s paintings and other artists from the Leipzig School, and I love the indulgent layering of information in Julie Mehretu’s paintings. There are many artists in my generation that I follow, but I am always particularly stunned by and secretly jealous of Emil Joseph Robinson’s pictorial invention.

EH: I also love Emil’s work. He’s definitely a painter of our generation who ups the ante for all the rest of us. Earlier in this discussion, we talked about what a low percentage of art students actually go on to make art consistently years after graduation, and especially as their primary professional activity. As a fellow fairly recent but not brand new MFA graduate, I know how hard it can sometimes be to keep the faith. What would you say has sustained you the most in your artistic endeavors?

ES: I think faith is a great word for it. Every new painting is a leap of faith. I make the big canvases before I have any idea what I plan to paint on them, and that’s a huge investment of time, money and effort. Even if I had a clear visual idea of what the painting would be, I didn’t know where I would show it or if I would ever recoup the cost of making the painting, and I never know if it will be any good at all as a painting. I very deliberately ignore those questions and anxieties when I start something new. I get the best ideas for paintings while I’m actually physically painting, which might mean I start working with a bad idea but get a better idea while I’m in the middle of it. I usually never show the first painting in a new series.

Don’t wait until you have an inspiration. If you do have a great idea, don’t hesitate if it seems too big or complicated. Learn how to make it while you’re making it.

Every new project is a step into the unknown, and making the painting itself can sustain you. To tell a grammatical lie but a practical truth, a painter is a verb. If you want to be a painter, you’ve got to be painting, and you either are or you’re not. Maybe that sounds harsh, but it’s also really simple. Keep the faith, keep painting, and do your best to align all the other practicalities in your life to support your painting.

i absolutely loved this interview/discussion. i also experienced the incisive honesty of eve mansdorf at IU. what has struck me about schweitzer’s work (as i’ve looked at reproductions over the last few years) is what seems to be the overall economy of paint, mark, color, and passage (of color, mass-shapes, etc). she never seems to under-work, yet never appears to reach that uber-density i sense in so many of my fellow IU graduates (myself included). there’s an interesting freshness and clear intelligence in the work. thanks for sharing all of this with us!

Very strong work…I enjoyed looking at the drawings and studies on her website. I like her attitude for making these large, complex paintings, that don’t always seem practical (financially, time-wise or storage-wise). Bet the farm, you’ll figure out why the paintings needed to be made afterwards!

Terrific work, Elise!

I really loved your art.It looks so realistic and the colors really blend well. My all time favorite painting of your is “The Tiber River Valley Sun” because it brings peace and I have always been a fan of art representing nature.

Beautiful, passionate luscious color and paint handling. Elise take the figurative out of the dreary classical realm. Gorgeous! A pleasure to look at.