Interview by Elana Hagler

(Ed. note: untitled cityscapes are approx. 6 x 6 inches and are oil on panel)

click here for larger view

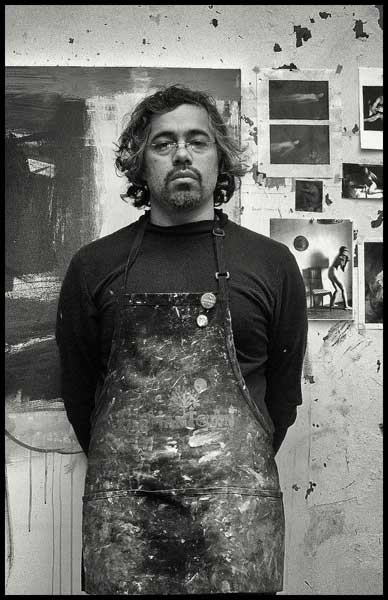

Arcenio Martin Campos attended New Mexico State University for studio arts, and then the University of New Mexico for studies in art history. He began drawing on his own as a child, and between schools acquired much of his fine art education from independent study and private instruction in the human figure. From 1999 through 2002 he taught small classes in cast drawing and facilitated open figure drawing groups in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Martin graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 2007, receiving a Certificate in Painting. He is currently searching for stories for the figures he’s drawn over the course of his life.

I don’t remember when it was that I first met Martin Campos at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but I do remember that I was immediately struck by his enthusiasm and seemingly boundless creative energy. I found Martin to be the sort of person that invigorates everybody around him. He is able to savor life on a level that most people can barely imagine, and all this shows in his vivid and enigmatic paintings. Martin’s eyes light up when he talks about painting, and that same light is made manifest and intensified in his work.

Elana Hagler: Thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview. What is it that first got you interested in painting and drawing?

Martin Campos: As far as I can recall, it was in the 3rd grade. I was living in the southwest, between Carlsbad, New Mexico and El Paso, Texas; it was the late 70s. My family lived in the middle of the desert with only a two lane highway running between the two cities. Pretty desolate. Big rigs would rumble from time to time along that road. So my first dream was to drive one of them. That above anything else. I loved the sound and the power. I do remember, at that young age, the sense of power these trucks evoked. I cried my eyes out when I was told I was too small and too young to drive one. My third grade teacher handed me a sheet of paper and told me that I could draw a truck and pretend I was driving one. This is my first significant memory of drawing coming into my life. Painting came much later.

EH: You first studied art history. What lead you down that path and how did you redirect yourself into a life of art-making?

MC: I did not receive my degree in Art history but I got really close. I spent many years embarrassed about that fact. As you get older, I think you tend to see how life develops patterns. Things get clearer. At least as I get older, I am increasingly becoming aware of how fate has a hand in things; mysterious things happen for a reason and turning my path to the creative part of me had a life of its own. You figure out how to follow your intuition.

With my academic studies, I was just biding time or at least my subconscious, it seems, was just finding the time to break through in regards to me being an artist. At the University of New Mexico, I was considering being a teacher, but really, under the surface, it was just a matter of time. Our Art History program at that time went through a drastic shift and I dropped out after a year of looking for possible graduate school options. This path led me to Philadelphia and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. That is when I left the idea of being an Art History professor and reclaiming what had always been real for me. So the redirection was no real redirection, but just following the path that was always there. Seeing paintings for the first time while visiting the East Coast and visiting the Academy definitely sealed the deal.

EH: Your studies at PAFA with Bruce Samuelson, Murray Desner, and Alex Kanevsky obviously had a huge impact on you. Could you pass along some nuggets of painterly wisdom that you absorbed from these wonderful painters?

MC: Their impact was one that I was not expecting. Upon my arrival at the Academy, I had a mindset that was far different from the one I have now. Now, I don’t know if that has anything to do with what I had in me the whole time or what the Academy had in store for me, but my decisions prior to my experience at PAFA were based on premeditated moves. My art beforehand was cut and dry. It had a beginning, middle and an end. With all that said, the most profound and fundamental shift these instructors had on me was to make me aware of how a work can be an ever changing and shifting organism. Art as an organism: a painting, a sculpture, or a drawing as a thing that can constantly move and be adapted.

So for me it was not as much a change in specific formal elements as a leap in thinking, and the ability of these instructors to pull out the artist that I was the whole time. That was the hidden treasure of the Academy.

EH: It seems that in your recent body of work, you are dealing with invented and remembered bodies and environments. What role, if any, does observation play in your work?

MC: Observation comes mostly from my periphery. Not so much what is in front of my field of vision. In the past, I always was reactive to a specific visual cue and focused more on that as a subject. Much credit goes to my fiancée for being such an inspiration in that regard. She was the first artist I met who worked from a more intuitive sense; creating pieces based on an internal struggle or a hidden visual cue. Now, of course, we all do that in some form or another but for me growing up in a small town and seeing someone do it right there in front of me, that was the whole enchilada. I just didn’t know how to get there.

My studio is strewn with visual cues and photo references. I dedicate sketchbooks to certain models I work with and key in on their lives and stories. I also work in their space, which I find is more comfortable for them, and they tend to be more gregarious and forthcoming with the stories of their lives. I take the scads of drawings and sketches to my studio and work from the residue of those moments. It is the experiences married with the drawings from those models, and the tons of reference material, that spark a painting. My last body of work was based on structures and forms and how both relate to one another. I dedicated that year to filling my studio with wood and photos of old, dilapidated buildings amongst figure drawings. These days, I tend to like an overwhelming amount of material in front of my field of vision to extrapolate from. This clears my mind to do the sorting out. Somehow, I clear it up in my work.

EH: What is the role of surface and touch in your paintings?

MC: It is becoming more and more important, especially after the last group of paintings done in 2011 to 2013. There was one piece in particular where I found myself reaching for plaster dust and throwing it onto the painting. My last studio had crumbling walls of plaster. I just did it as a gut move one afternoon. Just like you would reach for a napkin to wipe your face or to catch a sneeze. I distinctly remember when I did it and later on sitting down and realizing what I had done. I was creating imagined structures by using products of a structure! Now this is coming from someone who started out drawing academically and abhorred any kind of mixed media move of that sort. Somehow, something was always there inside of me that wanted to get that feltness out. I remember wanting to feel that wall in that painting so strongly that I did that gesture. It was the situation which called upon immediate and subconscious truthful action. These days I key in on that—or try to not be too conscious of it and let my reactions mingle freely. I just keep my studio well stocked with weird objects that will act as triggers to such moves.

Killing it to Live, 2013, oil on canvas, 58″x56″

EH: Could you talk a little about the role of lost and found edges in your work, and of the creative and destructive impulse?

MC: For me lost and found edges are determined by the juxtapositions of the subject matter and music I listen to. Currently, it is flesh against wood or steel (that is, buildings). Soft against hard and cold. I tend to favor musical structures with odd time signatures. Right now, it is progressive rock to the chagrin of most of my friends. I devour the lower end and the percussion of this genre of music. I eat up all kinds of sounds but right now in the studio the drumming of John Bonham and Bill Bruford coupled with Chris Squires bass structures are key to the way I lose and find my edges…..As for the impulse for destruction, I am becoming more and more comfortable with killing a piece for the want of the felt impulse that started it. We all do it in some form or another; it is what makes art after all. Some are just more blatant than others in the manufacturing of it. I love the tension of maintaining the semblance of a recognizable image with the expressive move, where I am at that precipice of destroying it. I named a painting Killing it to Live after that very notion.

Snow Scene 2010, oil on panel, 24″x24″ (detail)

Undertow 2010, oil on panel, 24″x24″

EH: Would you tell us a little about your use of color?

MC: Color is not too important until the subject begins to speak to it—then it becomes exciting. I really key in on my subject, how fleshy and how primal it is. I do not have a set palette and I just grab tubes out of a pile and use them. I know where all my reds, yellows and blues are in my studio. I just reach for what I need intuitively. If it doesn’t sing on the canvas or board then it gets shoved around or scraped off. Thinking painting is what I call it. Liquid thought. I do have to say that my experiences with painting en plein air have been crucial. This practice has made me favor working with very saturated color as arbitrarily as possible. This gives me the option to adjust and to look for areas of weakness in the outset. Find the culprit at the start and annihilate it. So color is very important after all, but not for the reasons most would think in regards to what I do.

Worm Woman, 2012, oil on panel, 24″x18″

EH: Why paint the female form?

MC: The million dollar question. I have been making connections to this recently. “Recently” meaning the past four years or so. I somehow see the answer connected to my sisters and the nurturing maternal figures of my upbringing. The juxtapositions of these forms against structures—structures as symbols of strength and fragility—which are attributes of the women in my youth.

Tulpehocken, 2012, oil on panel, 24″x18″

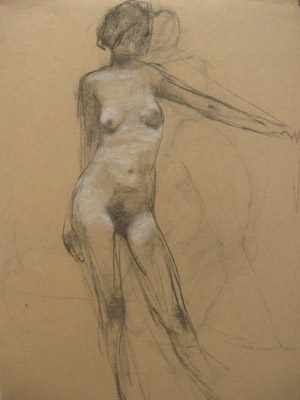

Untitled Drawing, 2012 – charcoal and pastel on paper, 19″x12″

EH: Hearing your thoughts really gives some great context to your paintings. Thank you so much for taking the time to do this, Martin. If you could go back and give your eighteen-year-old self any bit of advice, what would it be?

MC: To be a little more cognizant of the moment. I tended to have a delayed realization of this. As far as the formal elements are concerned, I would say stay the course with no changes.

Untitled Drawing, 2012 – charcoal on paper, 19″x12″

Untitled Drawing, 2012 – charcoal and pastel on paper, 19″x12

Love Martin’s landscapes. Very responsive and beautiful. Cheers! -H

Martin is a joy to know as a person, and his work is always a sincere pleasure to behold. Great interview!

Loved Martin Campos work , it’s so alive , relevant , makes you want to move and act , Great!

inspiring …

Your paintings are an inspiration..

Just saw your exhibition in Paris and loved it. Many thanks. I found it inspiring.

Very good work

Only recently became aware of Martin Campos, and his awesome work, and his love of line/paint! Totally exhilarating surface/texture, a rawness that spells beauty to me.

New Mexico, as well as Mexico, has always been a special place for me. The rugged land, the smiling dear people, and the amazing food, have long been favorites…. I feel that in Martins work,

Bravo, and keep them coming. He is one of the most exciting painters today!

Bravo, Francine Shore