by Caren Canier

I studied with Philip Guston from 1974-76 in the MFA Program at Boston University. Looking at my work, he would not likely come to mind as an influence, but his teaching had a profound impact on my development as a painter. At that time, Guston was well known for his lyrical, Abstract Expressionist paintings of the 50’s and 60’s but had fallen out of favor with his gallery and the critics following his return to figuration. At the time, it would have been hard to predict the overwhelming acclaim and influence his late work has had on almost two generations of younger artists. In 2015 he still seems to be the artist of the moment and his popularity has spawned a multitude of painters who emulate his late work.

I sometimes wonder what Guston would think of the proliferation of contemporary painters making, cartoonish, messy images with thick, and sometimes, encrusted paint. Many of these paintings borrow the most apparent, stylistic aspects of his work to ironic and sometimes cynical ends, while seldom embodying the underlying pictorial structure and formal intelligence that make his paintings great. I haven’t seen the recent show “The Guston Effect” at Steven Zevitas Gallery in Boston in person (Link to online viewing ) but I viewed the work on line. While there are some fine paintings in the show, it seems to me to be an example of the current craze to capture the superficial look of Guston’s work while, for the most part, disregarding the substance. The title of the show says it all: to speak of the influence that one artist has on others as an “effect”, seems to me a fairly shallow way of considering the relationship.

As a student, my work never looked like Guston’s and it’s unlikely that it ever will. My own sensibility is quite different from his and I always felt that he was respectful of the difference. Although he seemed to enjoy the flattery of having some of the students emulate his work, he didn’t harbor any bias against other ways of painting. His love of Piero della Francesca and especially The Flagellation of Christ is well documented, although certainly his work bears no superficial resemblance to Piero. (In 1975, when Piero’s Flagellation was stolen from the Ducal Palace in Urbino, he told a group of us that a good friend had called him and said “Come on Phil, give it back”.) In addition to Piero, I remember that he expressed approval of the reproductions of my pantheon of heroes that hung on the studio wall—Vermeer, Balthus, and Gillian Pederson-Krag, my undergraduate teacher, among other more obvious choices, such as Ensor and Bonnard. (He disapproved of my reproduction of Georges de la Tour, saying that the use of back lighting in his work disrupted the plasticity of forms. By the same token, he also criticized Piero’s fresco of Constantine’s Dream because of the back, night lighting, saying that this was uncharacteristic of Piero.)

In response to the “Guston Effect”, I have decided to chronicle my memories of Guston as a teacher to reflect on the way in which he influenced a painter whose work does not resemble his own, and in doing so, hopefully reveal more of the substance of his work and teaching.

In 1974, upon completing my BFA at Cornell, I had a choice to make regarding graduate school. I visited Boston University after learning of my acceptance there and fortuitously saw a show of new paintings by University Professor Philip Guston, who was teaching in the MFA Program. I didn’t exactly like them—I didn’t know what to think of them—but they stayed with me. For weeks after returning to Ithaca, I found myself thinking about those giant heads, French fries and cigarettes, strange and, by common standards, ugly images described in thick, sensuous paint. They were haunting. I kept looking at the catalog from that show—it’s a great little catalog that I still look at 40 years later—and slowly the paintings grew on me. Their poignancy and sensuality began to feel beautiful. I decided to attend BU to study with Guston and respected Bay Area painter James Weeks, whom I had met the previous summer at Tanglewood.

The first semester was difficult. The studios were inadequately lit with poor ventilation. It was hard to spend extended periods of time painting in the grad facility without feeling sick. Guston came to Boston once a month, accompanied by his wife, Musa, to give crits and anticipation on the part of the students before his visits was high. He would come around to individual studios and a flock of students would follow him, listening reverently to his comments. Once a month we were all a nervous wreck before, during and after Guston’s visits.

Guston was, for the most part, either extremely complimentary—“Marvelous!” was his favorite adjective—or extremely negative in response to student work. I don’t recall much in between. He was charismatic and his enthusiasms were infectious; his criticism could be harsh. He was never didactic or formulaic and seemed to respond from the heart. I remember that one time, when he was in the studio of a classmate, he became very quiet, looking around, seeming to search for words to express his feelings. Finally, he stammered, “You know, the more I look at these paintings I just want to take some white paint and cover everything up.” The student was devastated. Jim Weeks was usually the one to pick up the pieces after Guston’s visits, as he met with us more frequently. Weeks was a steady and stabilizing influence that was more likely to offer concrete and specific suggestions regarding the craft of painting and our work. They seemed to get along well and respect each other in spite of the fact that they were entirely different. For me, they complemented each other perfectly.

On another occasion, I remember Guston asking permission to work on a student’s painting. It was moving to watch him work, swiftly and fluidly while he talked about what he was doing. He loved to talk and was extremely articulate.

Another time a student working from observation asked if he should include or omit the radiator in an interior he was painting. Guston was visibly irritated and snapped something to the effect of: “who cares about a radiator and whether you leave it in or out?” Blunt, but so true.

To one of the students in the program who had been rigidly trained to follow a linear process in developing his work, Guston said that painting things out is still painting, and just as important as adding to the painting. “You’re still painting when you get rid of things.” He encouraged us to take chances and to respond to the painting itself rather than a fixed, methodical plan.

The process he encouraged sometimes seemed totally at odds with the traditional methodology of the undergraduate painting program at BU of the 1970’s, where many of my classmates had studied. Sometimes it seemed strange that he had chosen to teach at that particular school, with its decidedly academic program. But he said that he wanted to teach at BU because it was one of the few places where they were actually teaching us some skills and techniques of painting and drawing. He decried the loss of traditional curricula at most other art programs, where the advent of Abstract Expressionism and Pop had eclipsed most traditional, representational training.

At the beginning of my first semester, I remember showing Guston a landscape of a sunset that I had painted in Ithaca the summer before. He said, “Look at that sunset! It’s like a Hallmark card but it’s good.” The implication was that it was corny but good because it was sincere and genuine. And about a painting of a pregnant model I had hired, he didn’t necessarily like the painting but he thought it was great that I wanted to paint a pregnant woman and did so. He encouraged authenticity and sincere emotion in our selection of subject matter and certainly not the kind of ironic statement that is so prevalent in the art world today.

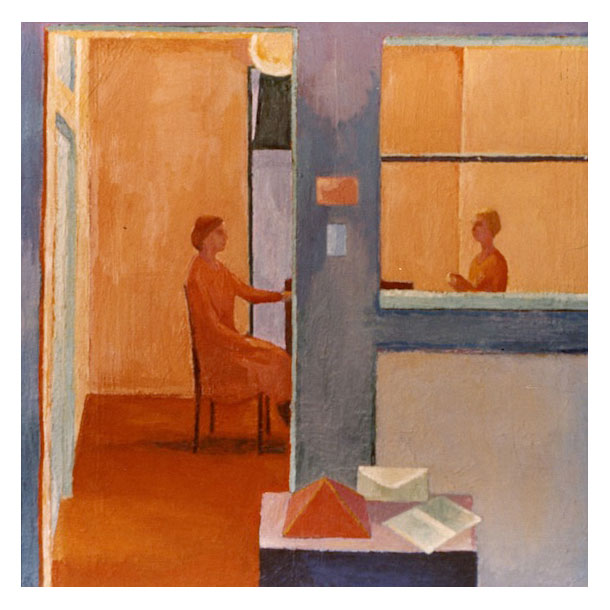

Caren Canier, Two Women Having a Conversation, 36 x 36 inches, oil on canvas, 1974

Toward the end of the first semester, I showed him my painting Two Women Having a Conversation. I explained to him that the painting had been a failed assignment for Joseph Ablow’s graduate seminar to make a 36 x 40 inch painting of two figures in an interior. After the assignment was over and the painting harshly criticized, I had doggedly continued working on it. I cut off the bottom four inches to make it square and compulsively pushed it to its conclusion. He responded enthusiastically, saying, “You were possessed!”

At the end of the first semester, plagued by headaches from the paint fumes at school, I moved into a storefront on Walnut Street in Somerville that became a two–person, live-in studio, first with classmate John Felix and later with Susan Mastrangelo. Since we were working large and it was difficult to transport paintings back to campus, we would drive both Guston and Weeks, separately, out to Walnut Street for crits. Guston, sometimes accompanied by his wife, would visit us alone or with only a couple of other students who came to hear what he had to say. It was wonderful to spend time with him without the big crowd; even transport time alone with him in the car was exhilarating.

One time in the spring of 1975 when Guston and his wife, Musa, came to the studio, John and I served them coffee and donuts. We were sitting in the kitchen talking about the posters and reproductions of Italian Renaissance paintings that were hanging on the walls around us and he asked me where my name came from. I recounted the story of how my father grew up with the surname Cohen, an invention of Ellis Island, but as an adult had changed his name back to Canier, an approximation of what he knew his father’s name to have been in Ukraine, because it was hard to find a job in NY with a Jewish name. Guston never said a word about his own name—I only learned that we had this in common years later when I read his daughter’s book, Night Studio. Guston was particularly loquacious that day and when he and Musa left the studio, he addressed me warmly and kissed me goodbye. At the time I didn’t understand this uncharacteristic show of affection but in retrospect I realize it was because of the story about my name. It was as if we were family. He was genuinely warm and not at all flirtatious—after all, his wife was there. Because of this and other kind gestures, I have always thought of him as a father figure. His bursts of anger and fiery temperament were not unlike my own father’s temper and I felt great affection for him.

Musa almost never said anything during the studio visits but she would look at the paintings with him. One time, when I made a self-deprecating remark about one of my paintings he said, “You have to have more confidence in yourself, you’re like her (pointing to Musa). She writes marvelous poems but she has no self confidence.” Another time he showed a few of us some illustrated manuscripts he had made of some of Musa’s poems that hadn’t yet been published. They were delightful. He also showed a few of us the original manuscripts of the Richard Nixon drawings that he had brought to Boston to show to a publisher. It was thrilling to see them, hear him talk about them and later, to see them in print.

(ARTICLE CONTINUES)

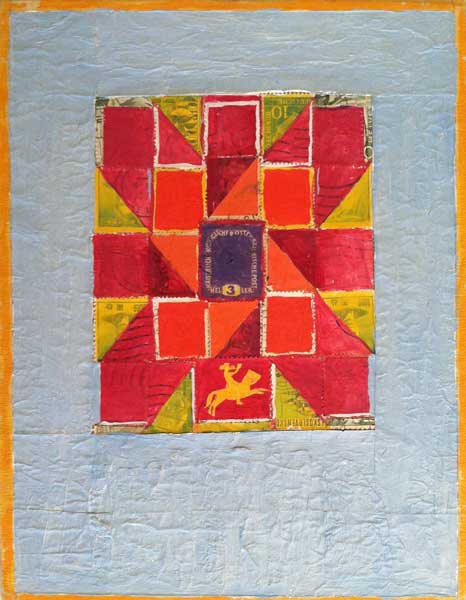

Another time, while looking at some of my early collages, that were thick with layers of highly textured oil paint, he said, “Do you mind if I touch these?—I like to touch paintings”, in that slightly breathless voice that I still remember well. He ran his fingers over the collages and considered them. I had been making strange, little mandala-like collages since undergraduate school and he was enthusiastic about them, perhaps more so than my more conventional oil paintings on canvas. (On the other hand, he told me to get rid of some mandala-like patchwork quilts I was working on in the studio. “Get rid of that stuff” was his comment about anything that smacked of the decorative.)

As I said, crits could be devastating, and I discovered this for myself at the beginning of my second year. The first crit of my second year was something of a disaster. I was experiencing a lot of personal problems and confusion about my work and my old solutions from undergraduate school were no longer working. There were so many things I wanted to paint, so many painters I was trying to learn from and emulate. I was trying to make the transition between painting perceptually and making figure compositions about personal subjects from my imagination. At the same time, I was making my little mandala collages out of postage stamps and other printed materials in an intensely personal and compulsive way. They were geometric patterns (not unlike the quilts that he told me to get rid of) but with little figures and heads peaking out of the geometry. I painted into them with oil paint and they had a rough, gritty texture that was satisfying. Those collages gradually evolved into the paintings that I make today, but at that time, there was no apparent connection to my oil paintings. I was hopelessly confused, trying to reconcile the different directions and felt miserable and scattered. I don’t remember any specifics of what Guston said to me that was so upsetting at that crit—he probably said that I was hopelessly confused and scattered—but I resolved not to show him my work again until I knew what I was doing.

For several months, every time he came to town, he would ask if I had anything to show him. I would say, “Not yet, I’m not ready.” He always accepted this answer respectfully. I buckled down, cleaned shop, threw away old habits and default subject matter, observed and imagined, and began to make big shapes of color on large sheets of paper without thinking too much about what I was doing. I set out to try to discover what was essential in my work. I wanted to find out what exactly were my internal form sense, my internal color sense, and my most personal vocabulary. I felt like I was on a quest to discover a visual language for myself. What came out was non-representational but architectural, a world of spatial cadences that suggested space and movement through it in a non-perspectival way. When Guston finally saw the paintings at the end of the semester he was very supportive. I think he sensed that I had come out the other end of a long, dark tunnel and although the paintings were still undeveloped (I later heard from another student that he had said this to someone), they had something, and I was on my way. Imagine my sense of satisfaction when I arrived at the opening of the MFA Thesis show to find my new paintings front and center in the exhibition.

As soon as I finished grad school I moved to New York and began painting figures again. With some distance from the difficult times I’d experienced in Boston, I realized that I still wanted to make paintings about people and the places they inhabit. Studying with Guston and Weeks had given me the wherewithal to try again to make representational paintings in the spirit of my heroes but at the same time, with my own, personal vocabulary.

Less than a year later, I was on my way to the American Academy in Rome, having won the Rome Prize Fellowship. Guston was one of my recommenders and I am forever grateful to him for his support. I saw him only once more after finishing grad school while visiting his show at the old McKee Gallery in the Barbizon Hotel, shortly before leaving for Rome. Musa had just had a stroke and although we talked briefly about my upcoming year in Rome, he was understandably very distracted. I learned of his death in June of 1980 while I was back at the American Academy in Rome as a Visiting Artist. My father had sent me his obituary in the mail.

Plasticity is the term that Guston always used to refer to the substance of painting and the tensions of pictorial space. His paintings are messy but they’re also masterfully taut in composition. Underneath the seemingly slapdash execution, his paintings are quite formal and reveal the high regard in which he held the masters. They’re humorous, but reverential rather than ironic. Few of the so-called Guston-influenced paintings that I’ve seen recently have the plasticity, cadence and gravity that connect his work to the great paintings of the past that he so admired.

As he said at the end of the film “Philip Guston: A Life Lived” made by the San Francisco Art Institute, Guston loved painting. Watching that clip from the film always brings a tear to my eye. He loved to paint and he loved to talk about painting. The way in which he spoke about art was highly emotional and personal but also deeply rooted in his understanding of the traditions of European painting. He had an uncanny ability to wed intense, emotional expression with highly formal, pictorial structure, which is what made him a great painter and an inspiring teacher.

Artwork and more information at Caren Canier’s website. An interview with Caren Canier for Painting Perceptions will be completed in the near future.

I never met Philip Guston yet his early abstractions were so curious and interesting to me with their atmospheric tones. I was told “He used white as an eraser to reshape a form” by Larry Day who did know PG, and this felt right when I looked at the paintings.

The later paintings still challenge me with their cartoonish images. My regard for him has remained strong despite that fact, as he is such a wonderful painter, who as CC said loved the tradition of painting and tried to make his work rise to that level of sincere expression with a tautness of composition.

Thanks for writing this memory of your time with him at BU.

Thanks for your comments, Bill. And best regards –

Caren

What a beautiful, beautiful piece! Bookmarked for inspiration.

Thank you!

Great writing and love it

Thanks, Wendy!

Caren’s wonderfully sincere and informative tribute to Guston might initiate a series of such essays by others who acknowledge their debt to powerful teachers, whose indelible work and words live on beyond their deaths. I can’t agree enough that “effect” carries totally different connotations than “influence”. They might almost have called the show “The Guston Affect.” Bravo!

Thanks for your comments, Lincoln. This is an interesting idea and brings to mind the insightful essay you wrote about Gabriel Laderman for the catalog of his retrospective at the University of New Hampshire Art Museum. It would be good to see excerpts from it reprinted under the guise of such a series. Caren

Nice article about Guston! Lots of hacks in that “Guston Effect” show. They also can’t seem to exhibit without each other’s presence. I totally agree on your assesment of it.

Caren, This is a beautifully written piece of a great teacher and painter. It is insiteful, articulate, and he comes alive again for me. Thank you for writing this! I remember so well those crits, and everything he said carried a “weight” which was profound.

Thanks, Susan. Your comments mean the world to me as confirmation of my memories since you were there! The intensity of those days on Walnut Street seems like yesterday…

One of the highlights of my many years of gallery going was visiting the McKee Gallery to see the figurative paintings by Philip Guston. I found the visceral quality of his paint thrilling.

Thank you so much Caren, and thank you for sharing your experiences of Guston when you were his student.

Thank to you, Ginnie, for your comments. We still have to get together!

Yes, I know….we are WAY overdue!

All best,

Ginnie

Thanks Caren for the well written piece! Memories of his comments always bring him back to me, and I think you speak for many former students about the Guston acolytes who don’t really get it and group shows that purport to reveal his “effect”

on painters. His most important message to painters was to find one’s own creative voice, and he urged us all to pick up that mantle- the “look” of something being relatively unimportant to him. He was interested in life in painting and finding vitality, something “plastic”! That movie kills me… especially when he is walking throughout the museum galleries and looking at his own work, touching the paintings.

Thanks, Grant. It’s good to have my memories and perceptions affirmed by people who were there. He was a force!

Caren – your article is a wonderfully evocotive personal story. Thank you for sharing it with those of us who never got to know the man. It will always inform how I look at his work in the future. You were clearly blessed to have him at such an important time in your development. Great article.

yes, a beautifully articulate man… I wish I had known him.

I enjoyed your recollection of this time in graduate school. I’m finishing my MFA at Boston University right now. Its resonating heavily. Thank you.

Dear Caren,

It’s been a long time since we studied together (with Langdon, too!) at Tanglewood under Gabriel Laderman….

I enjoyed your memoir of Philip Guston, who I interviewedt at the McKee Gallery in the old Barbizon Hotel circa 1977…A fascinating guy!

Warm regards,

Barnaby Conrad