Review by Thaddeus Radell

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

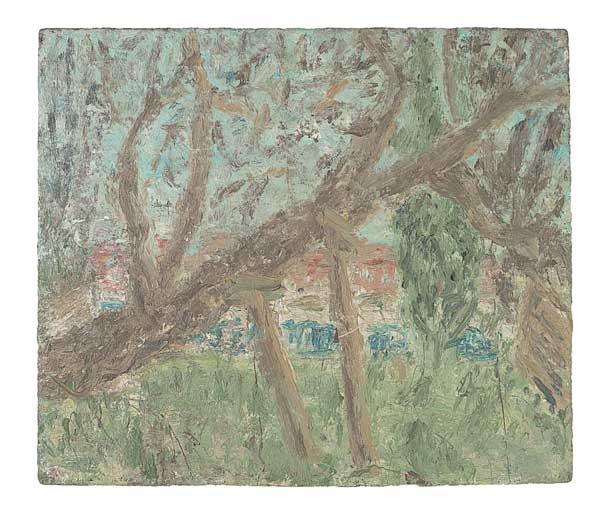

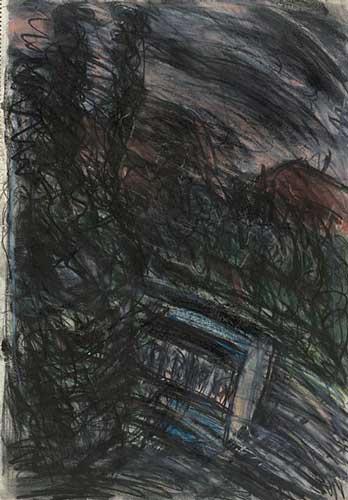

LEON KOSSOFF Cherry Tree, Winter 2006-7 Oil on board 36 1/4 by 42 3/8 in. 92.1 by 107.6 cm.

click here for larger image

The current exhibition of Leon Kossoff, London Landscapes, at Mitchell- Inness & Nash is an inspiring testimony to the ripe dense fruits of relentless toil. On view are dozens of fraught drawings with nine seasoned paintings scattered amongst them, like so many scarred and sea-hardened pilings holding fast in a swirling, brackish tide of charcoaled space. Indeed the drawings—so riotous is their process, so declarative in their presence—risk overwhelming the spirit of the paintings. The weighty seriousness of the paintings throatily responds to the challenge, however. In strangely ponderous dirges of light and movement, they anchor and calm the fervent surge of drawings.

The above shows a rare 2010 television interview with Leon Kossoff where Kossoff discusses paintings created in response the Old Master works at the National Gallery.

Along with Frank Auerbach, a close friend and fellow member of what R. B. Kitaj labeled the School of London, Kossoff developed an aesthetic whose essence was an expository yet visceral process of pronounced and devastating tangibility. It is not uncommon for an artist to leave traces readily visible as palimpsests of the thought or feelings that were used to construct the image. In such drawing, one often is able to read the unfolding of the image as line builds on line, shapes shift and evolve, values dissolve and reconfigure. The ability to read and follow the evolution of a drawing adds to the viewer’s experience and heightens his emotional response. In painting, as opposed to drawing, the evidence of the preparatory drawing that supports and informs the image was conventionally buried under layers of paint, until such giants as Matisse and Giacometti unabashedly offered the trail of their pictorial flight up to the scrutiny and judgment of the viewer.

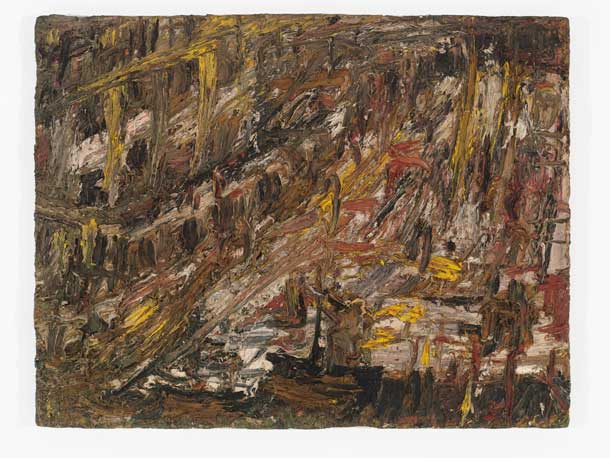

LEON KOSSOFF City Building Site, 1961 Oil on board 48 3/4 by 62 3/4 in. 123.8 by 159.4 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

The process of Kossoff, and Auerbach, is even more starkly unmasked and articulated with a different emphasis. After discovering a motif, his London Landscapes, for example, he attempts to understand what its meaning is to him. Even more important than the visual impact of its inherent form and physicality, even more important than visualizing a synthesis of its spatial possibilities, Kossoff considers its ontological claim on him. This meaning is never easily excavated from the highly complex motifs that appeal to him, and his method is to attempt to decipher it through numerous, and seemingly ferocious, essays of prolonged and rigorous contact. Fought through and through, session after session, the paper becomes battered and scarred, a dense testament and homage to Sisyphean effort. Each newly discovered motif births into a series of drawings, each often more scoured and tortured with a dizzying flight of marks than the former. What is of interest here is that the marks are not so much built, the relationship of phrases tempered from the pentimenti of previous marks, but that each successive stage of the drawing is started after the complete destruction of that preceding it. Thus the drawings are not realized so much from advancing the shapes and refining them analogically, but rather returning each time to the beginning, surely more informed by the constancy of observation, but pulling deeper into a more intuitive mode. From each effacement follows a new heroic effort, a fresh initiative to discover a more profound resolution of his distinctive graphic phrasing—a drawing that will cohere more stringently to an ineffable meaning he only hopes to unearth. Indeed, one feels that Kossoff arrives more at a truce with his image than a resolution.

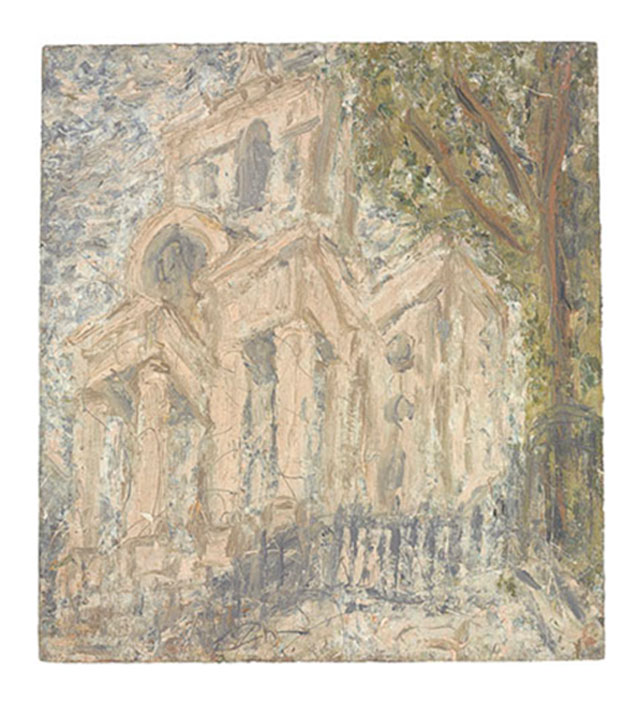

LEON KOSSOFF Christchurch, Spitalfields, 1999-2000 Oil on board

56 1/2 by 51 1/4 in. 143.5 by 130.2 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

His choice of motifs is often confounding views of streets, train stations, subway platforms and building sites. Their daunting complexity may, in the end, facilitate his quest for the transfiguration of his subject from the dogged act of observation into something more personally meaningful. From drawing to drawing in any given series, the same basic structure of the motif re-emerges, but given the constant flux of traffic, either vehicular or human, his eye is kept constantly alert to harnessing the elements into a new configuration, deeper essence. In such drawings as Outside Kilburn Underground, nos. 1 and 2 (1977), the architectural structure and even the location of the figures remain very nearly identical. However, the actual groupings of figures or the unpredictable presence of a car, each time demands a new response from the artist and poses new threats to the drawing’s equilibrium. In the latest drawings, the series Arnold Circus (2008-10), views of a street, a pagoda of sorts, or a flight of stairs are warmly juggled around the format with every individual drawing held precious to the moment by a varied cast of pedestrians, loungers, cyclists and dogs. These late drawings are lighter, both in their mode of execution and in their resulting spirit.

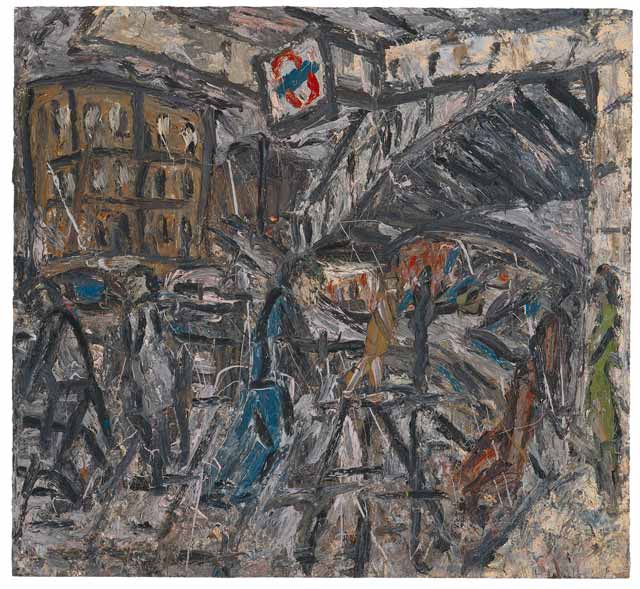

LEON KOSSOFF Outside Kilburn Underground Station, 1984 Oil on board 77 1/2 by 83 7/8 in. 197 by 213 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

Most of Kossoff’s drawings, as opposed to the Arnold Circus series, exhale a brooding existential air. Their gravitas is palpable and they never pause in their dark digging for a meaningful exchange with the viewer. Certainly such works as Willesden Junction (1962), Demolition of YMCA Building (1970) and York Way (1967) speak a somber syntax. The magnificent series of drawings from 1990, Train By Night, that opens the exhibition, is of an enchanting, dark, dark poetics. Even Cherry Tree, Winter (2006-7) is a grimly etched, almost sinister evocation of crippled strength. But it must be said that Kossoff’s abraded and eroded surfaces, no matter how desperately his struggle has darkened his page, never result in an effect of gratuitous scratching around simply to heighten the expressive content.

LEON KOSSOFF Outside Kilburn Underground no. 1

1977 Charcoal and pastel on paper 25 by 30 7/8 in. 63.5 by 78.5 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

The images are always luminous. Scuttling forever throughout the maze of thatched-thick charcoal stroke-upon-stroke is a pale blue, a chided white, a rose-tipped finger of dawn. The Arnold Circus drawings are different. The searching is still there, and the doubt. But a calm has settled on the subject, the lines less intensely scratching for phrasing, the tone more gentle and accepting. Late works, perhaps wiser.

As the drawings work themselves through and Kossoff deciphers what he needs to begin the massive undertaking of an actual painting, the doomed board on which he paints suffers similar multiple bouts of sustained and distraught struggle as the relentless slapping and slopping, scraping and scrapping, amass the image. The frenzied speed of the marks evident in the drawings is slowed to a more solemn, measured pitch and though the physical application of the paint is still inconsolably furious, each graphic mark now more decisive and resolved in its phrasing. The fugitive memories of furtive figures in motion are still there, although some are now so resolved in the artist’s mind as to become actual portraits of his family or close friends. Reworking the drawings from 1977 into the masterful painting Outside Kilburn Underground Station (1984), the movement has been hammered into syncopated rhythmic glyphs of striking expressiveness.

LEON KOSSOFF Demolition of YMCA building, London, no. 2

1970 Charcoal on paper 23 1/4 by 33 1/16 in. 59 by 84 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

Early paintings such as City Building Site (1961) and View of Hackney with Dalston Lane, Dark Day (1974) are less successful. Somehow these paintings remain deaf, inert, dogged memories of effort, the thick dull encrustations never attaining the ethereal quality of such later works as Cherry Tree, Winter (2006-7) or Christ Church, Spitalfields (1999-2000). Here, despite the evident angst of toil, despite the desperation born of doubt, Kossoff manages to coax and trouble his surfaces of these later paintings onto a level of softly muted luminosity that is almost of a celestial radiance. The heaven-bent columns and arches of the church, the defeated and crutched fruit tree—both are testaments to Kossoff’s power to sublimate the materia prima into living, radiant form. The ever-unsettled Giacometti once asked Jean Genet if his sculptures “won” by being cast into bronze, as opposed to remaining in plaster. The ever-enigmatic poet replied that it was the bronze that won. “For the first time in its life, the bronze has just won. Your woman, it’s a victory of bronze. Over itself, maybe.” (Genet, L’Atelier d’Alberto Giacometti). The same might be said for these epic works of Kossoff, the paint reaching beyond and achieving something greater than itself. Are these pictures a victory of paint over itself? If not quite victory, at least an uneasy truce.

London Landscapes continues to enchant until the 21st of this month. Mitchell, Inness & Nash, 534 West 26th Street.

Please Note: This show will also travel to LA to the L.A. Louver in Venice, CA 23 January – 1 March 2014

LEON KOSSOFF Train by Night no. 2 1990

Charcoal and pastel on paper

23 7/16 by 16 1/2 in. 59.5 by 41.9 cm.

(Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash)

The paintings seem to be marvelous. London landscapes seem to rock until 21st. Sad that I missed this golden opportunity.

Marvelous article, deeply moving work. I love Kossoff.

Nice i like all these paintings so much. these are really amazing and also great work has done on it.