Review by Thaddeus Radell

In John Lees’ current exhibition at the Betty Cunningham Gallery, the broad orchestration of intoxicatingly layered texture, ineffable nuances of color and spectral imagery combines to create an overwhelming presence of physical Beauty. Such Beauty, so impeccably and consistently constructed, its cultivation so apparent, soon becomes, in fact, disturbing. The undeviating articulation of high aesthetics becomes suspect, the surfaces redundant, even complacent. Yet, to Lees’ credit, once the initial visually stunning impact of the Beautiful has receded into this rather dogged ritual of exquisite, painterly palimpsest, and then allowed a second, more sustained viewing, the truly electrifying and poignant aspect of this exhibition emerges.

As Kenneth Clark surmised in his book Looking at Pictures, every encounter with a work of art can be seen as initiated by some sort of visual impact. That moment elicits an intellectual or emotional response, which consequently either engages, palls or leaves the viewer indifferent. In the case of these works, the impact is not derived from the notional subject of any given piece. Indeed those subjects initially read as quite monosyllabic and pale when compared to the complex and luxuriant phrasing of the paint itself. Lees’ strength appears to be in his sublime process of building time-hewn incrustations of richly layered paint into surfaces that define expressive, luminous and delectable paint application. To cite a single example, in Lake (2004-2013), a curved horizon of densely lustrous caput mortem shields a scurried flotsam and jetsam of softy radiant semitones. Here Lees couples his sensuous handling of paint with an acutely cerebral discernment of warm and cool color harmonies to adroitly caress the form.

Each piece in this exhibition hovers within close parameters of this refined and succulent ‘painterly’ aesthetic. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, the viewer’s interest in such overt Beauty is difficult to sustain and soon subject to wane, visually deafened by the alchemical sirens of Pigment and Oil. Discovering flattened tubes of paint buried in the surfaces is equally disconcerting, adding to a growing impression of a certain textural gratuitousness. William Corbett’s catalog description of Lee’s methods confirms that indeed Lees includes old palettes and studio floor-hardened paper as supports for his work. As David Cohen concludes, in an insightful 2008 review in the New York Sun, ‘the emotionally wrought sense of labor-intensity and devotion, in other words, is particularly achieved rather in the way a framer or cabinetmaker distresses wood to get an antique look.’ And thus the Beauty of this work is disturbing, both for its unnerving consistency, and for its seeming affectation.

Even more disturbing, however, is the fact that despite these grievous sins, this exhibition remains powerful, evocative, emotionally compelling, and, yes, beautiful.

It is, in fact, at this critical point of the spectator’s visual saturation that this work begins to awaken through the belated recognition of its topic. Philip Rawson, in his fine book, Drawing, describes the topic of a drawing as having two aspects. “First is the tenor, which promotes the extension of forms into space; second is the special meaning enclosed in the topic.” He then continues, “the meaning lies not in the tenor, but in how it is treated,” and “the point is that the topic of the work is something in which…a special numinous power is felt to reside.” The point here is that, for Rawson, art cannot consist merely of the tenor, or structural development of form. ‘The tenor is…the bare skeleton of the visual idea which can provoke us if we are artists to project on to it, or if we are spectators to accept the projection of, the imagery and visual ideas into which is condensed our experience of what it is to BE.’ The implanting of such an ontological context within his work is what elevates Lees’ efforts to another plane. Contemplating the belabored surfaces of his work, just before Tedium lifts its baleful head from the splatters, scrapes and blisters of those enigmatic caput mortems and soulful dusky greens, the topic of the work rouses itself from seeming single-mindedness to become a revelatory, numinous projectile directly on target: the target being the inner cradle of the viewer’s visual memory with its myriad emotional associations.

The tenor of Lee’ images vary, yet are all quite direct and, indeed, simple. A field, a stream, a bathtub, an angel from the Cloisters, a man in an armchair, a portrait, a clown. Such simplicity of subject is deceptive and allows this initial thundering of the physical to dominate, and indeed usurp the meaning inherent in these enigmatic works. Once one allows the topic of these images to swell beyond the painted surface, or rather, once one allows the virtuosic nature of the paint to become more than surface, the meaning of the assorted notional references becomes the real dialectic. Not that either the process used to create these images is unimportant or that the inherent meaning of these images could be equally well expressed in another manner. Indeed one cannot possibly imagine such a static composition of a bathtub yielding so evocative an image without such a rigorous and nuanced use of surface. Lees’ surface reveals itself as an exceptionally potent and exquisitely engineered, lusty conduit of a meaning that is so elusive, so rarefied that one cannot help but feel elevated into a state of grace.

Within this captivating exhibition, five paintings are of particular, numinous scope: Courtyard, 1986-2013; Man Sitting in an Armchair, -2013; Mater, 1979-2012; Clown (Beachwood Canyon), 2001-2012; and Dilly Dally, 2011.

Courtyard 1986-2013 Oil on Canvas 10 1/2 x 14 1/2 inches – image courtesy of the Betty Cuningham Gallery

Courtyard, presented in an alcove all to itself, is one of daunting beauty. The imposed cloistering of the hanging is echoed in the scene itself, a view of a deserted courtyard with a small collection of ponderous, silent forms. One-point perspective is blatantly enhanced by an elliptical cropping of the format and both pictorial devices serve to funnel the composition towards an enigmatic monument of some sort. This disconcerting, sentimental, even rabid, manipulation of the viewer’s regard toward the monument is eventually, and quietly, overcome by two poetically brilliant moments. The first, just behind and to the right of the monument, is simply an olive tree stated with a simple, symbolic beauty reminiscent of the Italian Primitives. The second, by far the more intriguing and simply pregnant with implied meaning, is a dimly lit passageway that leads off to the left of the picture. The mysterious luminosity of this suggested passageway with its low, top-lit wall and grey-shrouded tree offers infinite seed for meditation. The intelligence of this picture is palpable, its beauty resilient.

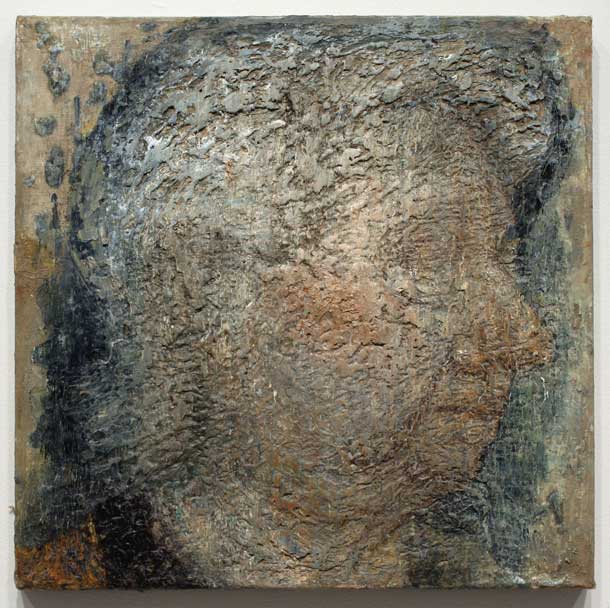

Mater is a portrait of the artist’ mother that frames her head tight into the format, a close-up that would normally account for a pronounced degree of observed detail. Instead, Lees offers the viewer an image as furtive, yet present, as the ghostly passageway in Courtyard. Importantly, the form of the head remains solid, despite the sullen merging of any given contour into the indefinite surrounding space. Here the weight of the paint is less beautiful, though no less expressive, shimmering as it does like silver beneath the peeling of a chipped tin ceiling.

Clown (Beachwood Canyon) is a haunting image where Lees has moved beyond observation, portraiture or memory associations into what critic Benjamin Genocchio expressed as the ‘visionary.’ Here the clown, with all its echoes of Watteau, Derain, Picasso, and even Cezanne, is conceived of as an artist, the painter himself. Lees’ excruciatingly refulgent technique, now fed a more intuitively inspired narrative, brings to birth an image of startling gravitas.

In Dilly Dally, Lees demonstrates an uncanny ability to elevate, through this relatively benign method of processed paint, a nostalgic scrap from his past into an image of surprising depth and a certain endearing poignancy. Corbett cites Lees’ masterly ability to process his ‘thoroughly American vulgarity’ into images that sustain and enrich the viewer. Indeed, Dilly Dally is derived from an early TV character. Yet despite the caricatural proportions and attire, this small panel reads as a soulful and radiant embodiment of childhood.

Man Sitting in Armchair (Blue Lamp), 2012 Oil on canvas 15 1/4 x 14 inches – image courtesy of the Betty Cuningham Gallery

Finally, on exhibit are three versions of a man seated in an armchair, all of which resound with deep feeling, compassion and a distinct sense of loss. Of the three, Man Seated in an Armchair (Blue Lamp) is by far the most refined and indeed is perhaps the most haunting and mesmerizing image in the entire exhibit. Surging from the recklessly exquisite paint, the deep wells of numinous undertones in other works are now fully breeched and brought into a quietly disturbing, palpable presence. The somber, anecdotal tenor of a man sitting in an armchair is endowed with an enigmatic, metaphysical weight that stops the viewer in his tracks.

This chance to witness the construction of the numinous on such an elevated scale is not to be missed.

Lee’s exhibition at the Betty Cunningham Gallery runs through June 22nd.

The intensity and sacrifice of time investing in these paintings by the artist make me think of the unraveling of history.

It makes me meditate on the ethereal quality that can only be acquired through time, seasons, waiting… and a little dust.

In this I see a beauty that is counter to the fast pace of life today that is nearly impossible to escape.

I think the aroma of a masterful gumbo. It makes me hungry for more. That is why I keep coming back to the paintings of John Lee.