I recently ran across an essay on the Arts and Opinion website by John Gordon on the state of the arts as relates to painting from perception. John Gordon, a Wisconsin painter who runs a private school, Gordon School of Art.

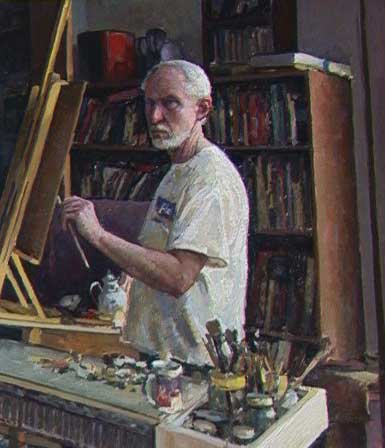

John Gordon Self Portrait in White T-Shirt

He makes many compelling argument for returning to perceptual based training in drawing and painting as a means measuring artistic growth and to return to the roots of art making. He states in his opening statement that;

“After nearly a century, modern and postmodern artists, critics and art educators have so liberated the term art from its traditional meanings and applications that in both the popular and professional senses of the term, it has lost its capacity to function as a word – that is it can no longer distinguish itself from what it is not. In both theory and practice, art is anything one chooses to make it; an artist is anyone who makes the claim. The lack of focus of the visual arts is due not only to its theoretical ambiguity but to its related lack of instructional coherence and measurability. It can be safely stated that art education is the only performance-based field of study that has neither a viable system of standards nor an established technical foundation. It is a field with no clearly defined, generally accepted goals, no established methodologies and no meaningful way to measure the progress of its students.”

He makes many interesting points some I agree with more than others. The article is a great point of departure for conversation for the comments section here. In an email he told me he is more of a purist on the subject of perceptual painting. I’m no purist for sure but lean closer to this than another direction. I also believe that perceptual painting doesn’t necessarily mean just painting from strict observation – that the process of perception also includes filtering vision through one’s personality and creative concerns. So when ten painters all paint a subject at same time you will invariably have ten completely different paintings. I mention this because sometimes painters in their efforts to paint the perfect apple forget that most people already know what apples look like and are far more interested in how the painter might see and what new thing is possible to say about this apple.

John Gordon, in a way, says something similar in his paragraph:

“The common assumption that creativity is exclusively a function of the imagination fails to take into account the superior and more fundamental creativity of perception. Researchers in the perceptual sciences — like Charles Solley and Gardner Murphy (Development of the Perceptual World, 2006, Kessinger Publishing, 2006) — are in general agreement that seeing is not, as commonly assumed, a straight-forward, purely receptive process. We do not see and then think about and have feelings about what we saw. Thinking and feeling are part of the perceptual process. What we actually experience as a result of looking at a tree or an apple on a plate is not the tree or the apple, but a percept, a picture in our own brains. This picture is formed in the visual cortex at the back of the brain, and is only partially composed of retinal data (which is already pre-filtered to admit only a portion of what is actually out there). This remaining retinal data is combined with the memories of past perceptual, intellectual and emotional experiences into an image that we mistakenly assume to represent the outside world. In fact, it is a composite of two worlds: the external and the internal, the present and the past. So to abstract — to willfully distort or ignore the images of direct experience — is to depart, not only from the world at large, but from ourselves as individuals. Thus it can be argued against the self-expressive assertions of abstractionism that the most creative human function is seeing and the most self-expressive artistic act is painting truthfully what one sees.”

Copying nature without a good painting idea is can be just as boring as copying a photograph or painting abstractly without a good painting idea. For me, it’s more what winds up on the finished painting that is key, all is fair if the painting is has rich visual intelligence and emotional power. Many times, great painters working from observation are able to lose their self-consciousness through the intense scrutiny of their motif resulting in a less formalistic or mannered style and find their unique response to the subject. Some worry that painting is dead, it has all been done before and what’s the point if nothing new is possible. I like to think that every painter can make his or her unique mark, like our voice prints and fingerprints. Of course, you could say people are dead too but that’s a different matter… 😉

In the coming years it will be increasingly important to keep painting alive, to promote the admiration and support for strong traditional observation-based training as well as in the arts as a whole.

I hope people will go to the Arts and Opinion website and read this fine essay when you get a chance. Please return here and let us know your thoughts if you can.

Larry, thanks for bringing this John Gordon article to our attention. As I’m just about to begin teaching my two drawing classes at MICA once again for the fall semester, these questions have been on my mind.

I completely agree with his point that visual perception is much more than just passively receiving data from the outside. Rather our brains construct a picture in the mind combining the outside data with our own

memories, emotions, and god knows what else that lives in our unconscious. As you say, 10 painters painting the same object are inevitably going to give us 10 very different paintings because they all see a little differently.

This is a huge, rambling topic and I could go on at length. But for now let me just say thanks for the article and for getting my little mental wheels turning.

Larry’s post and Gordon’s article rumbled around my head this morning and led to my latest blog post “A Key to Creativity from Our Very, Very Distant Past”, dated Aug. 24 at-

http://philipkochpaintings.blogspot.com/

While I agree completely that we have lost the learning process in the arts, I’m disturbed both by this author’s tone, and by the fact that he is to quickly making absolutes to state his case.

My own “education” sorely lacked any academic training, and yet the means were at my disposal. I had live models in painting & drawing classes, even if I had no instruction to go along with them. Further, the school had a great library filled with the very examples of things we whern’t learning, so it wasn’t as if you couldn’t see this stuff.

There were still (I’m talking about the late 1950’s) private teachers who attempted to teach in a more formal manner…. and clear through the 1970’s, in San Francisco at least, there were teachers of great abilities, both as artists and as teachers, IF you went out of your way to find them.

I’m not sure if that is true today, although I personally know one in Seattle … and, its rather odd to have to pay for an art education that doesn’t function and then pay for a private one that does….. the only advantage of the school being the piece of paper! And THAT needs re-stating, because THAT is behind a lot of why students go to art schools.

However, having written all that, I have to say that more than a certain level of responsibility rests with the student. You can, after all demand you get the education you’ve paid for, and you can put a teacher against the wall as to why they don’t know a damn thing, yet they are supposed to be teachers.

Further, if you KNOW what sort of art you want to end up doing, at least if you have some idea, and I feel you certainly ought to have that if your going to look for instruction, then its up to the student to locate the school that gives what it is, he needs.

Cal Arts is no cheaper than the Academy of Art in SF…… so if you can afford one, you can afford the other.

Finally, while it would take me 50 pages to say what I really want to say here, I believe that IN THE END, I wasn’t harmed by confronting modernism, both as a form of art, and the modernist educational system. I see the kind of education Gordon may be hinting at, or moving towards, as being just as harmful in many ways; just as based on absolutes; and just as lacking in any human warmth as is his self portrait.

I’d hate to have to study with this man!

I would love to go further with this, so I hope other comments related to this article encourage it. Again, thanks Larry.

Philip,

Great post on your blog that you just linked to. Sadly, I doubt that I’ll ever find the time to read much Carl Jung but I suspect there is a lot to what you say about the “the active hand of the unconscious in guiding our actions…”

I particually liked the line where you say; “To look long and hard at the outside word ironically leads you full circle to discover internal keys to yourself.” I also agree that direct observation of the world is key to learning how to paint – regardless of what type of painting you will ultimately do.

Part of the problem today is painting students often concern themselves with less with learning the actual craft of painting and drawing and more with the ideas they want to paint about (if they only knew how!)

I’m not very hopeful that the art world and schools will change anytime soon but it is always great to hear of people bucking the trend and promoting a more traditional foundation.

William,

Excellent comment – I was hoping this post might stir the pot a bit and your comment pushes it in exactly the right direction.

One thing I liked about John Gordon’s article is that he is coming from a more modernist slant that what you often read online in traditional painter’s forums and blogs. The importance he puts on Cezanne’s beliefs on painting from direct observation is something I rarely see. Instead you often find rigid academic doctrinaires where the joy of painting is often lost and becomes more of a competition of verisimilitude.

The more I think about it, getting an understanding of what makes an image visually powerful and to find ways to encourage the student to not only learn how to paint nature but also to learn how to love the painting from nature and eventually how to find their own way of responding to it.

Anyway, the subject here is way too big to write anything intelligent in a few minutes. Thanks for your post

Philip,

I’ve been interested in Duchamp’s written statements on art (not his work per se, but his thinking) for a long time now. One of his most provocative dealt with his stating that creativity in a work of art existed in the space between the viewer and the object being viewed (I don’t have the exact quote).

I’ve always taken that to mean that I brought as much to the painting I was looking at, as the painter brought to it. I took away as much as I brought. What I’ve gotten from works I’ve loved, has been an opening into myself, as much as an appreciation of what the painter did. I’m more interested in me than in him.

Not only are we all looking at things differently from one another, as you state on your blog, but we each bring a different set of physical things that differ from one another…. there simply is no ultimate way to decide WHAT something looks like…. it looks like what you believe it looks like.

Further, besides bringing our own objectivity to a given scene, we each bring what used to be known as one’s “style”… I guess that dates me big time! I define this, as the visual outcome of what I’ve put on paper (I’m a water-colorist), the totality of my way of seeing and my way of painting so that you can see what it is I have seen. In other words, uniqueness .

I find that a lot of what we are currently talking about, and what Larry’s entire blog concept is dealing with, has been covered in many ways by the painters of the so-called Ash-Can School…… Henri, Sloan, Bellows, etc. Both in their work, and in their and their writings, they seemed to address these ideas daily, while they actively fought against the hide bound traditionalists both in the “schools” and on the art juries of their time.

“All great movements in art history began with a return to nature.” –Kenneth Clark. Bunk! Movements began with money, and it’s because of their collectable value that some artists are still known. The Impressionists would only be a small footnote in art history if people never bought them.

The thing to bear in mind is that this changing of the guard (the “directive to express the self through absraction”) is enforced by the elite ranks of what is now Art’s upper crust, mainly the gallery owners and critics who feed off of each other. Most of what they want to hang is “new” not “old.” They pick what they believe will sell, and that’s what drives their market. Art students want to be in that market to make a living, so that’s the education they expect (for the most part.) Those students then become teachers, and the circle of life continues, but don’t shoot the messenger. If newly released students only followed an older tradition, they’d better be looking for a full time job doing something else. There is a market for traditional works, but it’s very very small. Look who the big buck art celebrities are now. They don’t paint apples.

A direct market from artist to buyer has evolved in recent years and has hope of breaking down that gallery upper crust.

If art history hadn’t taken the course it did through most of the 20th century things would be pretty dull these days. We’d all still be painting mythological scenes.

David’s comments (above) deal with so much that each could become a blog theme all by themselves.

Kenneth Clark’s comment on great movements is based totally on his thinking England was the center of the artistic universe. As David says, it was (and is( bunk! (I prefer bull-shit, but that’s OK).

More accurate perhaps, would be the idea that great artists might have their training based on a perception of nature.

And what is nature anyway? We can agree on a forrest, or a stream… but what about a junk yard, or a downtown street? Don’t these “subjects” provide just as much by way of potential learning as a tree? And, when did a plaster cast become “nature”?

My tree’s, as such, were planted in holes in the sidewalks of my city…. they arn’t any less for not being in the forrest, and there’s a contrast between these tree’s and the 4th. Ave. Trolley that rumbles past them you can’t get in the forest, or in “nature”.

Art movements don’t necessarily begin because of money…. most begin because the artists find things in common and promote them in their work. True, once the money types SEE this, its promoted as a movement, and becomes self-fulfilling as such. But I give the artist far more credit than David does.

The situation of art students turning into art teachers that David describes is pretty much something that came into existence AFTER 1945. Before that date, there simply whern’t either the art classes or the art schools. Blame it on the soldiers returning from WW-2, and using the G.I. Bill to go to school, requiring the building and staffing of thousands(?) of new schools to service the need. And, once established, those involved certainly whern’t going to give it up… thusly, it continues, although todays economy is certainly hitting it where it hurts!

In my short time as an artist, I’ve watched the Museum go from a place that presented history to one that feels the need to predict it. In the beginning, I think this might have been an attempt to make up for the pathetic gallery system in the country, but now the Museum’s seem to be working with the galleries…. and don’t forget to add the so-called art critics and the sad sad journals we call art magazines…..

Where David mentions “A direct market from artist to buyer has evolved…” I’m assuming he means the internet. And yes, in my mind this is the most important step that’s come along in my life time.

I will miss seeing work first hand, but I can’t do that now in any case… there are probably 10 major exhibits world wide at all times that should be seen, so short of a Lear jet, the internet is the best possible solution.

I’d like to see some sort of panel that deals with how to protect both the artist and the buyer in this regard, as eventually this method of purchase will be open to all sorts of fraud, but that’s another problem.

Finally, the question of art history and the painting of the 20th. Century. Indeed, things would have been very dull if we were all still painting 19th. Century mythological scenes, or histories of the countries wars…. or the millions of yards of canvas wasted pandering to a public that had been convinced it wanted to peek at what nun’s and priests were up to, or wade in the bathos of a variety of sick and wasted children…. or perhaps worse, the millions of kittens and puppies committed to canvas after canvas.

But that was one of the principal reasons artists took to Barbizon, and others to boating on the Seine…. and just as those artists were personally fed up with the excess of nuns, priests, kittens and puppies, some painters today are fed up with the excess and the Academy of Abstraction and they are looking FORWARDS to realism, or what ever the critics will label this tendency that certainly is emerging…….

Oh, and David, I hate to tell you, but there ARE painters today doing mythological scenes!

“…there ARE painters today doing mythological scenes!” Don’t I know it. At least most of them try to be clever and anachronistic about it.

I don’t want to stray too far off topic, but to clarify: I certainly DO give artists all the credit for being the source, but for the most part, the promotion of their work is left to other “agents.” Other artists, such as Corbet, were quite vocal about their positions. Some were later added to groups by historians and crtitics even though they themselves had different politics.

The transition of student to teacher goes back centuries; although, the format of classes has changed. Before the 20th century students had specific expectations after leaving school, and for the most part it wasn’t much. Digging sewers was often given more respect. The structure I spoke of reflects the current state of fresh artists becoming “free agents” but still bound by a gallery driven industry. Professional artists becoming teachers is a common path, but not something I see as trivial or demeaning, I should say. It’s more about how and what they teach, and being fair to all forms of art but realistic in the career paths of students.

“Direct market” was meant as internet, yes, or whatever form it becomes. This is happening in other art forms too, like music and writing.

I should include that I highly endorce painting by direct perception. I follow the principle myself, to a certain degree. It’s a skill that has diminished in significance over recent years, regrettably.

David, I agree with a number of points you raise but I wonder if you aren’t painting galleries and the “art elite” with too broad a brush here. I believe some galleries have great integrity and combine promoting painters careers with making it a profitable venture. I would want any gallery to not only be supportive and knowledgeable about the kind of painting I do but also to be smart business people who are actually able to make money. Integrity and money making don’t have to always be opposing forces.

Larry,

In my limited expierence, I’ve found galleries to be made up of all sorts of combinations… some were very knowledgable, most were not… depending on how esoteric my technique(s) at the time was, or how rooted in alternative art histories my work was; some seemed to understand the gallery “game” but not know much about business; and some were great with the collectors, but horrible towards the artists. In all cases, I felt I needed to be there way beyond my role as a producing artist, and, unfortunately, to do a rather large part of what used to be the dealers job for them.

I’m afraid I also have to agree with David as to the galleries feeding off each other. In the area I live in, nearly every gallery is filled with revisionist history paintings of Native American’s, pre the coming of the Europeans, or Native American’s and Cowboys… or just Cowboys and their horses… and cows…… oh, and I can’t forget the every present cactus!

These ARN’T Remmington’s… there’s nothing original about them, nor is there much that’s authentic…. they pander to a taste they’ve created, in league with what’s called The Cowboy Museum of America…. and any gallery that doesn’t belong to this cabal is simply ignored.

To the best of my knowledge, the interaction between these galleries and the groups that sponsor and support them, echos what happened in the major East Coast galleries, but here its a new thing, its far easier to see and understand in its pure form.

Unfortunately, the business of art and the world of “being an artist” (for lack of a better or more apt description) have never been further apart than they are now.

If anything, David’s statement is just scratching the surface of this.

I think that “modernism” has done much more harm than good in the long term.

It’s more than obvious when one enters any gallery of contemporary art or check out the level of art education in schools and Universities.

I don’t want to use too broad a brush, since modernism is a very diverse term, and I don’t wish to imply that all 20 century artists are bad, far from it. Yet, the outcome of 100+ years of education under “modernist” strictures is here for all to see.

On the other hand, if one take a look at the turn of the century artists which did not feel comfortable neither on Academic nor on modernist ground, one could realize that 20th century art might have evolved into something more than just a collection of polka dots, unmade beds or blank canvases. (And no, I do not think that mythology pieces or puppy portraits should be viable answer to such “art”.)

These are some of my thoughts, I do not intend to start yet another discussion on this subject.

Did John live in Covington Virginia in the ’60s? If so I have one of his originals. If not, oh well.