by Elana Hagler

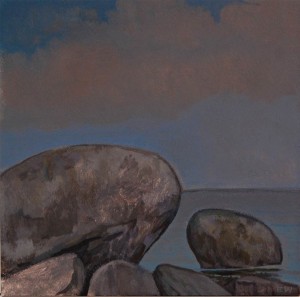

Elizabeth Wilson, Sunset, Greenport II, oil on panel, 24 x 24, 2012 – 2014

Elizabeth Wilson is a painter living and working in Philadelphia and will be having a show of recent work at the Rosenfeld Gallery in Philadelphia from November 2nd through November 23rd.

First studying at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., she transferred to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, where she received a four-year certificate in 1984. Prior to settling into her studio practice, she studied art history and anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. For nearly two decades she taught as adjunct professor and adjunct associate professor to fine art and architecture students, teaching design and drawing at Temple University, Philadelphia University, Community College of Philadelphia and The University of the Arts. She currently serves as acting vice president of the Alumni Council of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Elizabeth is best known for her luminous and intimate landscapes which have been appropriately described as having a “quiet energy”. Her work has been extensively exhibited throughout the United States and is included in numerous public and private collections here and abroad. Permanent collections include the Woodmere Art Museum, State Museum of Pennsylvania, U.S. State Department Art Bank Collection, Bryn Mawr College and McGraw Hill Publishing Company. Gallery representation over several decades includes Gallery Henoch, New York, Mulligan-Shanoski, San Francisco, The More Gallery, Philadelphia, Marian Locks Gallery, Philadelphia and Gross McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia, among others. In 2009, Rosemont College’s Lawrence Gallery, Rosemont, PA, held a Retrospective that included work spanning 30 years.

Elana Hagler: Thank you so much for joining us here, Liz. I’ve taken a fair bit of time to sit with your paintings and think about the things I want to ask you. I read your very interesting interview with Taryn Day from 2012 and you discuss your early artistic formation and your working process there, so rather than go over that again, I would like to focus on gaining a deeper understanding of your aesthetic vision and goals.

What I find so remarkable about your work is that although physically your paintings are small gems, they seem to exude this incredible sense of expansiveness in them. There is a wonderful impression of moving air and deep distance that holds this delicious tension with certain asserted edges that bring us back to the surface of the picture-plane. These edges and your painterly patches rhythmically take us on a 2-D journey at the same time that atmospheric perspective works to suck us deeper in.

Can you say anything about your consideration of deep space versus the assertion of the picture-plane? Is that tension something that you have consciously worked with over time, is it something that just comes naturally to your particular touch, or is it somewhere in between?

Elizabeth Wilson: The tension you describe Elana, between the picture plane and recessive space, does come naturally. At the start of each painting I am aware instinctively of a structure or hierarchal order; I see in a hierarchal way, very quickly. Whether looking at a landscape, an interior, figures walking on the street, a painting on the wall, or even listening to a piece of music, I can quickly pick out the rhythm, the dominant aspects of the composition, shape, color, light, shadow, texture and so on.

In each painting, I work to maintain the two-dimensional structure of the picture plane. At the same time, I make a conscious effort to break through the picture plane, giving equal consideration to the recessional space as I do the composition or design of the surface. The ‘activity’ of painting is mostly a subconscious event or series of events. I don’t have a formula, nor am I consciously making specific on-the-spot decisions such as soft versus hard edge; it’s happening intuitively like gears working in tandem with the exception of color and value transitions, because color is a highly considered technical discipline unique and integral to that painting and to its success. Only when I stand back to analyze what works and what doesn’t, in whole or in part, am I looking at it with regard to edge, color via relationships, shape, light, texture, visual harmony, the overall design and its effectiveness. Then, after that, I will rework where necessary. This process can take days, weeks, months and sometimes years.

EH: Your color seems to me to be less concerned with a literal response to nature and more with establishing a mood or concretizing a sense-memory. What are the ways in which you approach color in your work?

EW: More and more I’m working with a limited palette and integrate higher-key (prismatic) colors if I think the painting needs it. And I do straddle both the literal fence and conceptual fence on color.

As I evolved as a painter, I didn’t need or necessarily want to make an exact replica of nature or life, but instead wanted to draw from its energy. It was freeing to be able to tweak the color field to make a new reality that is very much based in the real world.

The attributes of a particular subject and creating a sense of place or personality are extremely important to me, but act more as a springboard. Color and light play a significant role but that has more to do with warm and cool color and specific qualities of light than an absolute realistic, in a photographic sense, depiction. I want my paintings to breathe and I use color and a limited set of tools when painting to keep the work and the subject alive.

In the late 1990s, I started a series of paintings in the Lake District in northwest England that has a particular coolness and deep blue-green color field. I was once criticized for not making the paintings warmer because then the paintings would be “more approachable” to buyers, which in the end was incorrect. By happenstance, a visitor to Philadelphia from the Lake District came to my opening and immediately recognized the area because of the particular nuance of green and identified the locations before reading the labels. When that happened, I felt that I had captured the atmospheric qualities and the essence of the place very successfully. More importantly however, it is my intention that the paintings stand on their own regardless of where the initial seed came from.

EH: How have your paintings and the things you are after changed over the years since you have left art school? What do you focus on more recently that you might not have given as much attention to earlier on?

EW: The most profound change in my evolution as an artist is that I am seeing more than I ever have before. Having spent so many years looking, and looking deeply, I am now better able to see nuance and layer in the world, to see beyond its surface. It is like “seeing into” or “seeing through”.

Because of this I am a much more confident artist now then I was during the first years out of school. As I touched on previously and which is related to seeing more deeply, I can intuitively grasp a complicated set of visual stimuli and reduce it to its basic core that ultimately gives me a sense of freedom. I’m not struggling to look but delight in what I see. This entire process inspires me; intrigues me. I’m now experimenting a bit with texture, which is something I left behind years ago. Whether it will last for the next series of work to come, I don’t know. This is reflected in the fact that I am working more with oil, rather than with gouache which I have used somewhat (but not entirely) exclusively for the nearly two decades.

For the past several years, I’ve been studying and painting water and rocky beaches on the Long Island Sound at the far end of the island. The landscape in the North Fork is infused with large dark shapes at dusk, which is the most alluring time for me. The topography is often times reflected in the sky. Perhaps this focus replaces the negative of space under the bridge or hill in a landscape against a large sky. My preoccupation with this form only became noticeable to me when putting together a lecture on my creative process and how I work. So there is a strong continuum, regardless of the subject matter.

In addition, a new series of paintings has been developing which I call, “Character Studies”. These are self-portraits that have aspects of people I know/have known or are personality types from observation that emerge subconsciously when I’m painting. These are painted from life, in front of a mirror. They are generally small, 6″ x 6″ average, oil on wood or canvas mounted on wood. This series evolved from a large number of oil on wood self-portraits that I began years ago but have never shown.

Part of my maturation as artist has included a strong appreciation for and alliance with abstract painters who bend reality, in part because of my natural preoccupation with structure and a shared aesthetic that is based on pure design. I began to really focus on this appreciation and alliance in the 1990s and they remain a constant in my creative life. Since then, I have found a place to marry the worlds of literal and conceptual reality and so, in a sense, I’m reaching backwards, taking parts I liked in my earlier work and using the skills and interests that evolved over time and re-making what I have been always searching for in my work, to make each painting a unique, intimate environment that invites the viewer to experience and offer contemplation on a multi-faceted level.

I think students coming to art school now are exposed to a world of images and writing that was simply not available (or easily available) when I was a student. We had to search through libraries and bookstores for what can now be located in seconds or minutes on the Internet. Truthfully, I am envious of the wealth of knowledge, visual and otherwise that students entering art school have at their fingertips. It might have taken less time to get where I am now in my work if I too, had that good fortune, but then, there is no substitute for experience when it comes to truly seeing.

EH: Much of your work is done in a square or almost square format. Why do you keep coming back to that specific shape?

EW: I never really left the square. I worked in a square format on occasion when I was a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. On my walls hung in the museum during my third and fourth year, were two large 60” x 60” still life paintings, along with smaller paintings that were rectangular and a combination of the two shapes. Without speaking the words, “design” or “format”, we were encouraged to work asymmetrically within that then popular format of the rectangle, because, it was implied, the square was too tempting or at least too easy to work because of its symmetry. When teaching design and drawing some years later, I would not allow my students to work within a square at first or symmetrically for similar reasons.

I have come to think of the square or near square as an object by its shape alone. It is an unexpected shape in nature. It is a fixed and powerful shape.

In thinking more about the square, I have noticed that it has proliferated along with the evolution of the Internet. I think it owes itself in large part to graphic design, which has become the one visual art discipline that has become mainstream out of necessity (website design, for example). The importance for visual readability and flow of web designs is essential and the square and circle have become big players today, graphically. The interest in late 19th and early to mid 20th century design and in particular art movements like Modernism, Futurism, Russian Constructivism, Dadaism and De Stijl have made a significant impact on modern life. I have to wonder if the Internet has been an important force in this interest.

And for painters, you can now buy pre-made square painting panels and canvasses. It seems the square has become the new acceptable and standard format. But to break the square and make something organic work, or not, within it and with it is actually a real challenge.

When I started traveling on a regular basis to England and working with gouache, I would take a book of paper with me that had near square dimensions, which suited me and my aesthetic and so that format as ‘object’ has endured.

EH: You stated in the interview with Taryn Day that you are interested in in the “subtleties of the changes between the permanent and impermanent landscape.” That’s a really beautiful idea. Can you elaborate more on that particular dichotomy and what about it you find so compelling?

EW: I have been a sky-watcher for as long as I can remember. For me, watching the sky is the most interesting, thought-provoking part of the landscape. Living in a suburb of Philadelphia, it’s rare to see large open spaces. I’m usually capturing glimpses when I’m driving or walking, looking up or at the end of a street between buildings or trees. I rarely see horizontally.

As much as I have an aversion to shopping centers, they have become one of the few places near me where I’m able to view an uninterrupted expansive sky. The skies I see that tell a story in the round; they are a space of transition and impending weather, from left to right, from top to bottom. They are almost never predictable and almost always in flux.

In contrast, natural or built landscapes are essentially static in their foundation with the exception of weather events, the changing light and the passing seasons. The energy of the sky and fixed landscape work independently though collaboratively, quietly and often times quite dramatically.

The ‘wow’ moments of late afternoon light in autumn that create strong contrasts, long cast shadows and shapes of color is something dynamic and visually exciting in its abstract beauty and nuance; it is something I grab onto visually. Just as wonderful however, are the overcast days where structure is less obvious, values are closer together and color is muted—there is a quiet poetry in those moments, which I deeply covet.

EH: You work both from life and from photographic reference. What do you do to “translate” the photos and keep the paintings from becoming too literal?

EW: I use a lot of imagery for painting ideas. I have boxes filled with decades old torn-out black & white and color newspaper images and magazine images and am still adding to them, saved for future painting ideas or reference. On my computer are fifteen or more years of images pulled off the Internet saved for the same reason. All the images I collect are carefully selected and some eventually discarded if they don’t keep up with my current ideas/current aesthetics.

The photographs I take which are solely for painting purposes (I’ve also been doing street photography as serious study) are taken with specific information in mind. First, I strive to compose the photograph well from the start. From the actual image(s), the bits of information I grab are those that allow me to remember a particular subject, light, shadow, shape, color, texture, composition…..essentially the abstract qualities.

But I do separate myself from the photograph, taking only particular aspects and rely on memory or years of accumulated visual knowledge. When I am working with a photograph, at some point I turn the photograph face down so not to rely on or be it influenced by it. I may bring it out at some point to re-familiarize myself with what I found so inspiring in the first place. Sometimes I never see what it was I saw.

That’s why a thumbnail sketch or color study is more valuable than a photograph (the combination of the two is invaluable) because the eye and the brain are capable of registering limitless nuances that the camera cannot. When I look at a thumbnail sketch, it becomes animated to me; recalling that exact moment (ie: the warmth of the sun, the smell of honeysuckle, the mosquito’s biting, a chorus of baby birds chirping to be fed, the song on the radio, etc…..). It can recall your state of mind, how you were feeling, what you were thinking at the time, your ideas. The sketch becomes real and tangible. By comparison, photographs are sterile references, so I have to be conscious of what I’m experiencing when I’m out taking photographs. Sometimes I’m painting and drawing in my head even when I’m out there photographing or just afterwards when I’m digesting what I saw and experienced.

On a side note, three and a half years ago nearly all of my sketchbooks were stolen by workman who had access to my studio. These sketchbooks were more precious than my paintings or even my photographs. It is a terribly troubling and deeply serious loss for me. Among these were sketchbooks spanning of five consecutive weeks in Europe in 1990 full of notes and sketches that also included self-portraits and drawings of my former husband.

EH: That’s heartbreaking. I’ve had work stolen, too. Most notably, my portrait of my grandfather was stolen when I brought it in to a class I was TA’ing in grad school. I can’t imagine someone actually enjoying a piece of art that they stole. Maybe one day these pieces will find their way back to us.

What are you after, Liz? What keeps you making your work?

EW: My interest lies with making little environments, a whole world of them. Sometimes they are based heavily on real experienced realities and sometime they are entirely invented. These are representational souvenirs of observation and thought.

Philosophically, I’m not really certain what keeps me making my work; why I need to do this. I can say it derives in part from a supreme preoccupation with nature at its core; its beauty, the wonder of it, its power and how humans and nature collide. Being in the company of great art, interesting music, dance, smart design and smart architecture (if not great architecture) as well as the extreme opposite of beauty or when beauty is derived from something ordinary or unpleasant, all plays a role in inspiring an idea. It generates a kind of energy and stimulates a need, if not a demand, to make images to record, to document, to reinvent.

Most honest painters will tell you, that there is an intellectual and physical battle going on in the studio every time you step inside and close the door. It’s an intense struggle between balancing what you want, what you don’t want and what the painting wants. When the painting is going well, it feels like an adrenalin rush of satisfaction. Sometimes getting to that point and being ‘in the zone’, so to speak, I wonder if I’ve forgotten to breathe. Those moments of euphoria during and after a long, successful battle stimulate a need to keep doing it (I am guessing). Part of that struggle is to make the next one better than or at least as good as a previous one, but at the same time you want the work to evolve as you evolve. It is a delicate balance.

You develop an enormous appreciation of what artists have always had to go through to make their work. Not just physical or financial sacrifices in order to work, but the intellectual battlefield of seeking perfection through years of intense observation, study, experimentation, patience, enormous self-discipline and very hard work. It’s part of the reasons we’re willing to travel 3000 miles away to see their accomplishments

Thank you Elizabeth and Elana. This conversation was inspiring.

What a fascinating conversation! Elana, your questions were engaging and probing; and Elizabeth, your answers were so enlightening. Having seen your show, I now have an additional level of appreciation of your work.

Elizabeth, I really appreciated your comments about your intention to maintain tension between the structure of imagery on the picture plane and breaking through to express deep space. I realize I have the same concerns in my oil paintings of landscapes. It was a thought provoking interview.

Nice stuff. Your dark clouds change the whole atmusphere of your landscape painting. Like a growing storm and the rolling thunder of sexual energy in a flash of light across the plains.

nice stuff,Elizabeth, I enjoyed your landscapes paintings the one’s done abroad seem to have a more personal feeling for you. your mediums express a personal energy and calm. What do you plan in the future works of your paintings? .

Have a piece that is signed by Elizabeth Wilson very similar in style to the painting of the woman shown in this article. Would love to know if it’s your work. Thanks!