by Elana Hagler

At a time when that which is loudest and brashest gets the most attention, Tamie Beldue’s drawings are a balm to the heart and mind. They embody something of the shattered, dream-like reality of Edwin Dickinson with the delicate observation and grace of a silverpoint drawing. Although all paintings and drawings are best appreciated in person, this is even more the case with Beldue’s encaustic pieces. Much depth and detail is inevitably lost in even the best photo reproduction, so I cannot stress enough how important it is to see these works in person. Beldue’s drawings breathe and shift. Her forms do not describe a world of certainty, but of changing aspect where the everyday gathers for a moment and slips away.

Born in upstate New York, Tamie Beldue is a contemporary American artist focused in mixed media drawings. Beldue received a BFA from the Columbus College of Art & Design and earned her MFA at the University of Cincinnati. Beldue has exhibited extensively in the US in group and solo exhibitions, including the Fort Wayne Museum of Art Realism Biennial, Southern Ohio Museum, North Carolina Museum of Art, Mobile Museum of Art, the Arnot Art Museum’s Re-Presenting Representation and the Fontbonne University Fine Arts Gallery. Her works are in the permanent collections of the Arnot Museum of Art, The DeYoung Museum, Howard & Judy Tullman Collection, James T. Dyke Collection of Contemporary Drawings and the Sandy & Diane Besser Collection. Currently she is represented by Blue Spiral Galleries in Asheville, NC and is an Associate Professor at the University of North Carolina Asheville.

Elana Hagler: Have you always known you wanted to go into art making? When did you undertake this path?

Tamie Beldue: I drew often when I was a child and seemed determined to draw even without ‘proper’ pencil and paper: those funny landscapes, the kind with the sun radiating beams of light from the top corner, on scrap blocks of wood or rocks, basically on anything I could find outdoors. And in coloring books, methodically, always inside the lines, but never filling shapes in as solid color, always transitioning value and working diligently to achieve a smooth transition of tonal ranges.

In 5th grade, I received several awards and certificates of recognition that I expected, in running and good grades…but I was shocked by an award in art. I remember racking my brain to think what on earth I had done to be considered good enough to be singled out. Even though I still wasn’t interested in art per say, the fact that someone else made this distinction was significant in raising my awareness of art and putting it on my radar as something that I was good at.

Later in high school, there was a foreign language requirement and I chose French and while I did fine academically in learning the language, I despised going to class because speaking the language felt so unnatural almost to the point of theatrical. I soon learned that as an art major there was not a language requirement, and between that and the fact that I could escape from school mid-day through the art room window quickly became end of the story, sign me up.

I remember then, even at such a young age always wanting to draw, not as homework, not because I was told to, but because I really actually wanted to. Friends would want to watch movies and I was always fine with that but I wanted to be drawing as well. I always felt that there were too many important things I should be doing and that watching movies would keep me too idle.

I don’t know where someone actually acquires this type of discipline, not the ability to be able to create a likeness of something, but rather the desire to. And I see this in my students; some do well in my classes because they are just that, good students. They always come to class, do their homework, putting in the required amount of energy to complete their work. However, it is those who are compelled to draw, who can’t help themselves, creating drawings even outside of the assignments, to the point of obsession even on class breaks. For them, it’s not about a grade but rather a way of life.

EH: Oftentimes, artists point to a teacher or two that was highly influential for them earlier on in their development. Was there any such person for you?

TB: I was fortunate and two particular influences raised my awareness of art as a possible way of life. In high-school I had Deborah Teska, a veracious, spastic teacher, now friend, who very positively modeled all of those qualities in an encouraging, explorative way. I specifically remember struggling with drawing hair, and her enthusiastic demonstration to convince me that it was the most wonderful thing ever to draw. She was my champion, honing my technical abilities, insisting on applying to top art colleges.

It was then, at the Columbus College of Art & Design that I worked closely with my late mentor, Charles Hall who, through countless conversations, taught me to see, moving me beyond copying appropriated photographs.

In the beginning he would only allow students to use a 2H pencil, forcing us to translate things such as black fabric into a value that couldn’t extend beyond high key, reshaping our entire understanding of relationships. I was finally mature enough to focus on drawing from life as a diligent practice (not to be confused with neo classical training) and understanding the idea of personal interpretation.

Later after college, I sat for Charles for two portrait paintings in which our conversations continued, discussing things like the meaning of relationships and the role of the ‘mark’ descriptively. With regard to my future, I trusted his advice and he insisted that I apply for an open teaching position, and I have never looked back.

EH: Could you describe your working method for us?

TB: I’ve come to a point where my work felt too formulaic, and the images seemed literally static, versus felt. So I’m becoming less and less concerned with a repetitive cohesive body of work and much more interested in what each drawing requires, regardless of what came before.

Working in my home studio, my preference is to work for at least eight hours at a time, although small bits of time cobbled together happens most often than not. While I prefer to work from life, accessibility dictates that my practice include photographic references. In the past I primarily would shoot my own photographs, typically at least a hundred or so for each ‘idea’, never working from only one and, I collaged photos digitally to understand new possibilities. Now though everything is experimental and evolving as I move away from my typical formal model shoot, searching for a more candid, everyday subject that isn’t staged, arranged or preconceived. As photographer Sally Mann says, “part of the artist’s job is to make the commonplace singular, to project a different interpretation onto the conventional”.

Watercolor is often applied first and I began using it as an underpainting when my drawings became larger, to intuitively establish value, color and temperature within a drawing. In Moving Light, I was interested in the relationship between the cool fluorescent light of the distant room on the right contrasted with the warm incandescent light in the room on the left and watercolor allowed me to subtly bring this difference and contrast into the conversation.

British painter, Diarmuid Kelley has spoken about knowing a painting is finished when he feels he is just “filling in”. Deviating from the familiar sharp point of graphite and allowing myself to explore outside of a standard working method, along with the use of broader materials such as; charcoal, pastel, collage and even oil on occasion, I alleviate the confines of a predetermined end and can accommodate the needs of each image as it develops.

In 2008, I began using encaustic medium to further illustrate the spatial relationships, and clarity of mark as it related to notions of recollection of subject. This is evident in my drawing; Tangible Identities, Blair I, where thicker layers of encaustic distorts portions of the tightly rendered face, while thin layers of wax allow the details of the earring to be clear and prominent. Recently, cold wax medium is used as another way to seal and protect the drawing as well as an impasto medium that provides a dimensional tactile presence to the mark.

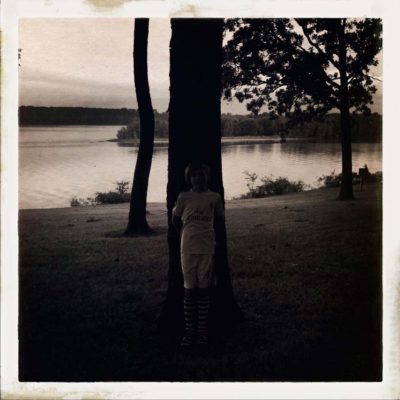

In a less serious, but equally important working practice where life and studio intersect, I work similarly to Andrew Wyeth as he prolifically sketched future narratives at Kuerners farm, or Sally Mann as she obsessively photographed the maturation of her children or like Gustave Klimt as he painted landscapes instead of figures while on holiday. I explore, utilizing alternative methods, be it quick plein air sketches beside the highway or utilizing the spontaneity of the cell phone camera to compose and create.

Last year, on the first evening of a thirty-day road trip across country with my nine-year old son, after 13 hours of driving, he accidently locked the keys in the van. Jokingly, as we waited for AAA I said, next time could you first let me get my drawing supplies out, in which he replied, you have your phone don’t you?

EH: How do you choose your subject matter?

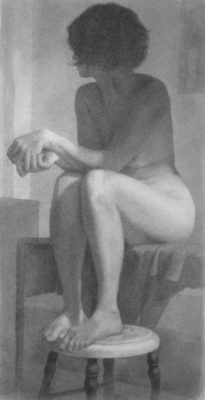

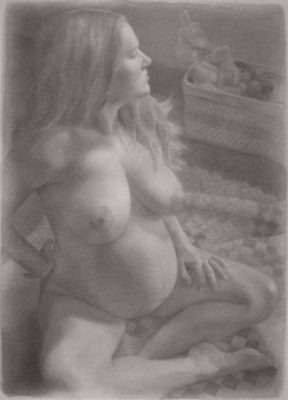

TB: When I work with the figure, I’m interested in body language, the subtle non-verbal clues some of which I am aware of in the moment, and some I discover later in the photographs. The camera really worked for me that way. While I was busy dealing with practical formal issues of lighting and composition, along with keeping the model happy and comfortable, working at high speed with the camera, I could understand a lot about the model in her setting with regard to how she is experiencing the moment beyond the obvious and literal. I read once that photographer, Richard Avedon said it took eight hours of continuously shooting Marilyn Monroe before he felt he got Marilyn without the persona of Monroe. I think this relates to the demands and expectations of societal norms to insist upon certain outwardly behaviors despite honest thoughts that may be occurring on the inside, I looked for evidence of this within my sitters.

With regard to that, I had always had models come to me, either in my home or campus studios, and I found there was a certain amount of rigidity and/or emotional detachment to the poses, because the models were unfamiliar with the surroundings and their body language specifically revealed this. To escape from the artificiality of staging, I began working with models in their homes to explore differences in posture when the model was at ease with and comfortable in their personal environment. In my drawing Enfold, this model owned a small loveseat that she would nap and read on for hours and knew exactly how her body fit the furniture. I think the pose that she took, with a leg draped over the edge was a familiar and intimate experience between her and the setting, rather than what I, as an outsider with my own ideas, would have directed.

Other times my subject matter is dictated by the need to illustrate a personal or social commentary to a broader audience. I have received comments that people would feel strange having an image or a ‘portrait’ of someone they didn’t know in their house, so there is a body of work in which I specifically address the idea that a viewer could have more of a response to a generic archetypal object that defines consumerism rather than the specificity of a person that defines humanity. Drawings in this series depict a singular figure that contrasts with an image that is associated with frivolous collecting of products, for example, a kitchen decorated with wallpaper, towels, clock, dishware, etc. all depicting a rooster, – thus, my drawing, Portrait of a Rooster.

EH: I see that over time your drawings seem to be moving away from solidity and towards a more fragmented appearance. Can you speak to that?

TB: More recently, I began questioning the ideas of traditional portraiture (that is, focusing exclusively on the details of the face and placing the sitter in a typical seated pose) by exploring the figure and its context interpretively, in ambiguous or illogical space that goes beyond the conventions of standard observation. I’m focusing more on figure-ground relationships and the patterns of light and shadow than on incidental details. This is evident in Knees, Socks & Hammock, in which the composition uses repetition of flat graphic shapes contrasted with the tension of disappearing rendered legs. My focus was more concerned with the chaos of formal relationships, so I found it easier to let go of logic and began to examine the abstract within the representational. However, while camouflaging or integrating the figure to sit within a larger spatial context, I still was not able to entirely let go of the figure, or what remained of it, as a conventionally rendered form, and allow a quality of graphic abstraction to supersede rational reality.

Interpreting interior spaces as patterned abstraction, is replacing a habitual figurative regimen rooted in rendering, and I’m allowing myself to investigate new approaches. And subject matter is not my only shift. Pastel, and now more recently vine and powdered charcoal are used to let go of the details early on. Edwin Dickinson said “the particular comes from the general but the general never comes from the particular” (I may be paraphrasing here). The details can be so damn familiar or alluring, and I was catching myself over-working drawings time and time again and sabotaging the pursuit of a more sophisticated response with an economy of mark. With that in mind, I’ve been looking at Antonio Lopez Garcia’s powerfully persuasive drawings, which utilize simplified abstract shapes to form relationships suggestive of literal subject matter. This approach masterfully executes his unique observation of life, rather than merely copying it. I seek, as Lennart Andersen says “to paint the place not the thing.”

At some point I expect to return to the figure, but only after I’m comfortable with being uncomfortable.

EH: When people ask you what you do professionally, do you call yourself a draftsperson? What is it particularly about drawing that calls to you?

TB: I do often correct people when they refer to me as a painter, not because I take offense to painting or that someone might think of my work as painting, but rather that the work isn’t made with the same cognitive processes as one might use to make a painting. There is a directness in my approach to drawing that keeps it more malleable for me, allowing the addition of any material necessary. Contemporary painter, Stuart Shils’ current work pushes the boundaries of what defines painting, working with the iPad and iPhone. This work can be perceived as drawing, sculpture, painting, and/or photography as he defies the confines of traditional oil and canvas, where materiality is not of as much importance as is the cerebral approach in the process of image making.

The way I feel about painting is a good analogy to how I felt learning a foreign language: foreign. I’m not saying that drawing is easier, but it’s more my native language and I don’t have an intuitive vocabulary for painting.

EH: Do you remember any particular breakthroughs that jumped your work up to the next level?

TB: Looking at my work over time you will find a definite progression albeit slow and steady over many years seemingly, without any drastic changes. Those for me happen more behind the scenes and ironically typically serve as a reminder to stay my current focused course.

Often I want to push boundaries, looking for an unfamiliar place outside my realm of comfort. Recently, on sabbatical I had a lot of time that gave me freedom to stretch my vocabulary. This of course ultimately resulted in a pile of awful drawings, which left me panic stricken half way through. But I continued working, even more prolific with my attempts, and the drawings finally began to coalesce with the right balance of understanding and uncertainty. It wasn’t that I needed to be looking or responding differently, rather a little of both, like standing in a boat, where you can be comfortable enough to stand, but always remaining on guard to compensate for a sudden wake. I quickly learnt that these bad drawings, or as Diarmuid Kelley refers to as the “naughty pile”, consisted of drawings that became about making an image rather than describing an experience.

A recent work, French Seamstress, was made in direct response to removing my personal relationship from the image completely; both with subject and the environment in attempts to gage the necessity of my experience. Ultimately, I have learned that perhaps it isn’t that my works, with the figure or otherwise, are too personal, rather, it may be that they aren’t personal enough.

EH: Do you find that your domestic life influences your work at all, or is your work very separate?

TB: Domestic life most certainly influences my work. In 2008 after relocating, no longer having convenient access to models, I became intrigued by the physical vulnerability of my then infant son sleeping in the most casual and unguarded positions in his crib. I made ten drawings, Sleep Series, fairly small and intimate, that pictorially illustrate these innocent postures, something as an adult, I am envious of.

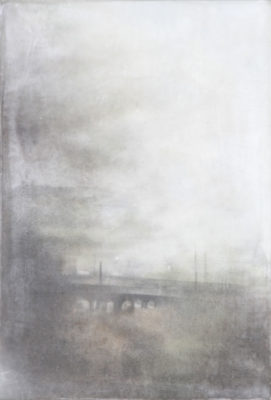

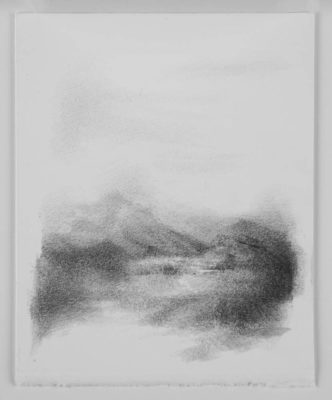

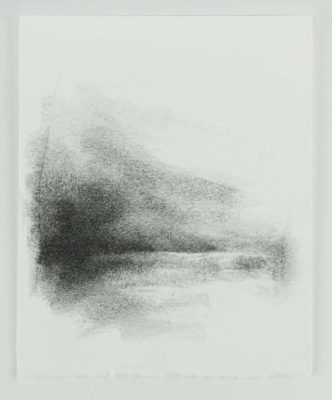

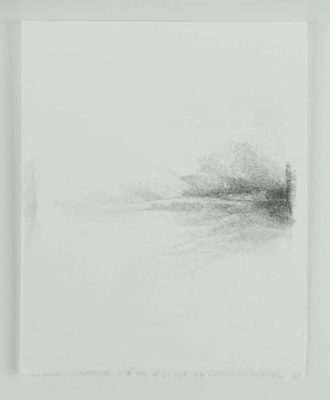

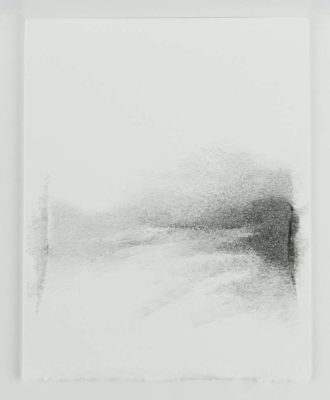

Later, my domestic life also influenced a series of twenty-five drawings titled Never Trust the Landscape. When my family moved from flat, rural Ohio to the mountains in North Carolina, we experienced soil erosion for the first time. The property we purchased had major erosion issues, which literally threatened an entire hillside. After working with the county environmental engineers to rectify and stabilize the land, we found years later that erosion had opened up another crack in the landscape. We fought erosion but the water always won. The instability had us on edge when a rain was forecast, and learned never to trust the will of the landscape.

This body of work also points to the energy received from this particular place. On reaching our forest ridge, we noticed that physical reactions occurred, for instance, our heart rates would slow causing a sense of calm & easier breathing, and even compasses no longer worked when brought to our property.

While living there I discovered that my husband was having an affair, and ironically he likened his attraction to the other woman to our draw to the landscape. The drawings allowed me to work through the contradictions of how energy so calming could create such destruction, just as the rain had so easily opened and eroded the landscape.

Furthermore, when removing my wedding band that first day, I was overcome by the imprint left behind in the surface of my skin, as though I hadn’t removed the ring at all. I wondered how much time it would take to visually erase what took twenty-four years to create. On closer inspection, I found this imprint to mimic that of a landscape – again the landscape! I approached each drawing as a complex duality of a landscape, examining the correlations between the ‘cracks’ of the landscape to the indent left behind in my finger. While each drawing marks another day that I expected the ring indentation to dissipate, the series when viewed as a whole mimic that of an undulating Appalachian horizon line.

EH: What have been some of your greatest challenges in your work in the past? Are there any particular challenges you are trying to overcome in your work right now?

TB: This is a good question. I, like most, have a lot of personal goals/challenges/hurdles, whatever it is you want to refer to them as.

The overarching challenge of the last ten years is reconciling what I know I can do, what I want to do and what I actually do. Elana, you write that my drawings breathe and shift, and this is something I work toward, but even more so, I want to get beyond the object of a drawing and create an image that negates the notion of a drawing. Unfortunately, the majority of the time, or even every time, I have no choice but to start again with a new piece. To continue pushing something that has already been worked, compromises the integrity of spontaneous mark, luminosity and texture of the surface. I have an understanding of what is missing within a drawing and an even greater sense of insufficiency for articulating it in either words or in the pictorial image. This dissatisfaction of enunciation is for me like an ongoing, moving target and a serious handicap that I’m continually addressing. Often, the studio feels like I am equal to a horse that wins races without actually catching the carrot he’s chasing. That said, I finish drawings specifically to allow for the possibility of a successful image, even without the carrot. How can I not think that this discipline will lead to something greater at some point?

Another challenge is the exposure to the bombarding imagery from social media. Frustrating as it is, the ability to see posts of work in progress, studio photos and finished work generally not available on official artist websites, is valuable not only for personal reference, but also to use in my teaching. However, the abundance of visual noise that I sift through often interrupts my private thought process, and unfortunately, the work that I am interested in can be just as damaging. At times, looking at contemporary art does not feel so different than looking at a fashion magazine, with color, media, subject, and mark-making trends that attempt to coerce and allure. So much work on social media feels like diluted copies and street corner knock offs. The challenge is not to become sideswiped by an overabundance of confusing imagery.

EH: If you could give any advice to all of us out there making art in the trenches, what would it be?

TB: This question perhaps dovetails the preceding one. The trajectory of engagement should be a personal exploration, allowing for questions like, what do you need from your work and what is your work needing from you? More than ever, there are so many opportunities, especially with art having such a massive online presence that becomes a reality in itself, for the unique voice of the artist to easily become pulverized. Commentary on social media, popular trends, sales that encourage us to revisit a similar idea and/or process, even praise with its best intentions can inadvertently and unexpectedly cause us to shift focus, testing our abilities to trust our own path, on what already may be shaky ground.

On the contrary, in turn, when looking at work by others, be it historical or contemporary, perhaps we should not spend so much energy judging its validity, in a hierarchical or qualitative critique.

This of course is all so much easier said than done.

Living in North Carolina, I have seen Ms Beldue’s work in Asheville’s Spiral Gallery. The thing that struck me right away was that they were certainly done from photographs. Now, many artists work from photos occasionally, including myself, but when an artist almost exclusively works that way the work suffers. I wondered if she projected and traced, then merely colored or shaded them in. I kind of got that feeling but perhaps I’m wrong on that point. I wish that she had addressed that in her interview because her stock would go up in my view if she did not use that method. Even so, I often find parts of her figures somewhat clumsy and /or flat. Her portraits, i.e. the faces, are quite well done however. I thought the landscape drawings, though small, were more evocative than the rest, but hey! that’s me. Also enjoyed the portrait of her by her teacher–honest with no pretensions.

I have known about Tamie’s work for awhile through social media, and I was finally able to see some of her drawings this summer at Blue Spiral in Asheville. She creates such beautiful surfaces which have to be seen in person to be fully appreciated. I was also impressed by the scale of the them (the ones I saw in the gallery) and the atmospheric qualities she invokes. Dickinson definitely came to mind, which to me is probably one of the highest compliments you can get. Wonderful drawings and really enjoyed the interview…thanks!

In some sense I agree with Mr.Celano about working from photography. It is almost impossible to find figurative artists who are willing to work without them and I think there currently is a great homogenization of style. When you look at the paintings done from the Renaissance to say the mid 1800’s (pre-camera) there was a greater variety of style and personal artistic vocabulary. There is no mistaking a Botticelli for a Titian or for an Ingres. There is a certain set to faces done from photographs. That said, Ms Beldue’s work does display a rare delicacy, in the Instagram age with it looming heads that are all too often slick and crude, She is a fine and original designer. And most notably she generously organizes an annual drawing show that I have been honored to be a part of.

A unspeakable lesson off inspiring art,thanks.