Susannah Phillips was raised in London and attended the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Her paintings have been in many solo and group exhibitions in London, New York and Provincetown, MA, and are included in numerous private collections. In 2014 and 2017, she was awarded the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation Residency. The artist lives and works in New York. She is represented by Bookstein Projects in NYC where there will be a solo exhibition of her work in January 11 – February 24, 2018. Susannah Phillips will be the JSS in Civita Master Class Guest-of-Honor in 2018 residence July 2nd to 23rd in Italy.

Beverly Acha wrote in December 2012 Art Critical review, Growing To Know A Place: Susannah Phillips and Landscape

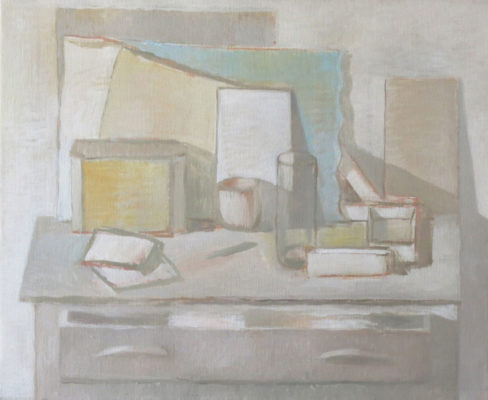

“…The absence of representational details grants these landscapes an unexpected second life. They have the capacity to suddenly flip to abstraction, for a moment losing their pictorial depth. Yet the muted and succulently specific color always shifts the landscape back into view. The change in light from painting to painting is sophisticated, creating strong implications of volume and space between landmasses. As you walk through the gallery, the landscape progressively reveals more dimensionality, with variations in the height of mountains, the position of the sun, atmosphere, and time of day. Time intervals between paintings seem no more than 30 minutes or an hour, allowing the artist to slow time down to the point of capturing the closest thing to what we can understand as the present.

Phillips’ subjects, whether landscape or interior scenes, are transformed into vessels for explorations into light, volume, and form. Like Agnes Martin or Giorgio Morandi, her motifs seem to have emerged from a metaphysical search, from a need to infringe on the barrier between the concrete world and ourselves, to reach a point just beyond our grasp. These new paintings and drawings straddle a line between spirituality and philosophy as they begin to utter the unspeakable, the nature of time and the instability of reality and perception.” –– Beverly Acha

Larry Groff: Thank you Susannah for your generosity with agreeing to this interview and for the time and attention with writing your responses to my questions.

Susannah Phillips: You’re welcome.

LG: What was growing up for you like and how did you decide to become a painter?

SP: I had a happy childhood despite having divorced parents, moving around and not really having a sense of belonging to any country. With my father, there were summers in Cape Cod with its artistic offerings. Otherwise, I grew up in London–I went to school at the French Lycee there–and Europe. Saw a lot of churches, frescoes, paintings, ruins. I spent one year in Athens when I was fourteen, and in the evenings we, my mother and I, would go into the Parthenon, walk around, have a picnic. There were no fences, gates or guards. That same year, I was taken to a Morandi show in Bologna, and that’s when I decided I wanted to paint. For me, Morandi was very approachable compared to what I’d seen before.

There are several painters in my family, father and sister included–it was on the cards to consider becoming one. And I was always encouraged to draw.

LG: I understand that your mother’s first marriage was to Arshile Gorky and she was close to many famous painters such as De Kooning, and Matta. Was that something she talked about much and influenced you in some way?

SP: I’d say the only important influence on me of the Gorky connection then, was growing up with his paintings. Some sort of osmosis. I’m not aware of when I first noticed them. The negative side was that I felt my efforts were a bit insignificant, as I thought his paintings were so beautiful.

And yes, I did meet De Kooning and Matta, but mostly the painters who came through the house were European: Helion, Craxton, Ghika, Paolozzi, Cloclo Peploe, to name a few, some of whom became important to me for their encouragement and example.

LG: You went to art school at the Slade and studied with Coldstream and Uglow. What was that like for you?

SP: Disappointing. I was looking for some structure, but it was the 70’s and classes weren’t compulsory. I mostly worked where I was living at the time, except for using the life room quite a bit and the print department in the first year. I didn’t have much to do with Uglow, regrettably. Coldstream was always friendly and supportive. Apart from learning about printmaking, I felt I wasn’t taught much at the Slade (partly my fault for working outside the school), however I’m grateful for those four years because it allowed me to focus on painting. In a way I regret not having involved myself more in the school. I’m sure I missed out on things. But I still have one valuable Slade friend with whom I talk shop.

LG: What lessons did you learn from Coldstream that still resonate in some way with you today?

SP: Possibly my grey-leaning, restrained palette might have something to do with Coldstream? Or with the English weather. In fact, at the time I was at the Slade, I was still much more influenced by American 20th century painting and Picasso than by Coldstream. Colour, surface and shapes attracted me more than the palette and soft contours of his paintings.

LG: What did you do after finishing art school?

SP: Oddly enough, it never occurred to me to do a post-graduate course. Hard to remember why.

I went to New York for two years and took odd jobs and painted in my bed-sit, which at one time was in Georgio Cavallon’s house. Loved–still love–his whites and dry paint.

After a couple of years, I returned to London. In my early thirties, John Craxton got me my first show there, in the gallery that represented him. After that, I moved to Montreal, raised our son and painted for years in isolation, and now here I am, in NYC.

LG: Did you ever feel the need to rebel against what you learned in school in order to find your own voice?

SP: The Slade imposed little on its students in those days. There wasn’t much to rebel against.

LG: What artists or art has been most significant to you and how you paint today?

SP: First there was Morandi, then I forgot about him and got interested in Spanish painters, Velazquez in particular, but also Titian, and many other early and late Renaissance painters. But at one point, quite late, in my thirties, I felt I was painting too many subjects at once and not developing as a painter, so I decided to focus only on still-life painting. Enter Augusto Torres, Braque, Cubism. I became more interested in composition and lost interest in recording everything in front of me. I looked at Derain for many years and, like everyone, I had many crushes: Cezanne, Manet, Matisse, Picasso, Poussin – all the obvious ones, even Guston. The list is long.

My interest in Augusto Torres, a more obscure crush, was in how he simplified, how he kept the geometry and structure in the composition and gave shadows importance. Lots of art and artists have influenced me. Even the Acropolis. Recently, I did a stint at the Albers Foundation, and during the following months, found a lot of rectangles appearing in my canvases.

LG: What more could you say about Morandi?

SP: As I said above, he was my first love. However, now I no longer look at or think very much about his work, although I’m always happy to see a few at a time and I would like to see more of his landscapes. I like the bunching up of his objects and his inclination to simplify. In fact, I think it’s time I looked at him again.

LG: I’ve heard you are friends with the painter Paul Resika, how would you say this friendship has influenced you?

SP: Paul is my brother-in-law (and friend), and he has been important to me. I’ve watched him for years in the studio. I took from him my habit of doing variations on a subject. I don’t seem to tire of working ad infinitum on many surfaces for one pictorial idea. I suppose I also got that from Morandi at the start.

LG: Many of your paintings, especially your still life, seem less to do with describing actual things and more about the mystery and poetics in the relationship between those things. How do you go about setting up a still life and deciding what to paint?

SP: I don’t have a stable method. I’m sure what I do is pretty standard. Roughly, this is how I go about it.

I have an idea, an urge, for a composition–the kind of shapes, the mood–before I find the objects. The objects are usually chosen for formal reasons–the shapes and shapes of their shadows play a large part. Often the objects have been lying around for years, collected as props. I have a feeling about an object when I see it, I recognize in it something that I see already as a painted object. Often the props are personal, for example I associate them with someone or they evoke a memory but It’s not important for me that the viewer be in on that.

When the setup is ready–objects will shift in the making of the painting–I make drawings, and then painted versions. These variations bounce off each other and, even though they tend to pile up unfinished, they help move things along. The first paintings are largely descriptive. I then go back to the original idea I had of the composition, and the objects become more an arrangement of shapes, nothing specific. By the time I am doing the later versions, I am no longer looking at the still life setup particularly. It’s in my head and in the studies. At this point I’m just making a painting.

LG: What tells you it’s time to stop working on a painting?

SP: It varies. Sometimes I like the painting, so I stop. (This is when the next version might begin). I recognize something in it that feels right. Other times I go on forever, uncertain, the painting killed, revived, killed again. The ‘finish’ stage in painting when I used to paint more faithfully from observation, was easier to catch–the picture had something to match. When the pictures are left in the studio for a time, I always see something wrong and tend to fiddle.

LG: Can you talk about how you use color in your work, do you restrict your colors in some way? What colors do you use most?

SP: I rarely use colours straight from the tube. I tend to mix them up. At some point, I discovered that Velazquez only used five colours–red, yellow, brown, black, white, so that’s what I picked. Big restriction. Sometimes I add a different colour, like turquoise, for example, but I have a hard time not mixing it out of existence. I do use ochre, burnt Sienna but no umbers. I love black, but I also make my own out of ultramarine and burnt sienna, or viridian and cadmium red deep, for example. I use Naples yellow pale, whites, cobalt blue, cerulean, manganese, cadmium yellows, oranges and green. I use the cadmiums mostly when I paint flesh.

I can’t work with too many alternatives. I wouldn’t know even how to choose other colours to add to my palette. The choice would seem arbitrary.

I love strong colors in other people’s paintings, but I am very drawn to murky gloom, twilight.

LG: What thoughts might you share with us about getting good colour in a painting?

SP: Not sure I know what you mean by good color. If you do, indeed, think I have good colour then having fewer colours would be my tip.

LG: What difference do you see in using colour derived from observation from colour that is completely invented?

SP: The important thing for me, whatever the source of the colour, be it observed or invented, it should work in the painting as a whole. I might drop the real colour of the object in favour of something I want instead; so, for example, a cloth that might be blue ends up being something quite else in the painting.

LG: What role does observation play in your work?

SP: Everything I do is related to something out there, but I usually have an idea for a painting before knowing how the seen thing, the motif, can be used for making the painting .

In my landscapes, I work from drawings done on the spot. Back in the studio, I invent with the help of those drawings. In my recent cityscapes I can only seem to capture what’s out there by not looking (because there’s too much information). All my interiors are of places that are important to me and that I know well.

LG: What might be helpful to think about for a student wanting to avoid clutter in a painting?

SP: Simplify… take things out!

LG: What attracts you to painting representationally? Would making paintings that are completely abstract interest you?

SP: Although I am very drawn to abstract painting and grew up with it, I have never been able to make one. For now, I need something to hang on to for me to make what I’m doing feel less arbitrary. Limitless choices overwhelm me. Ditto colours.

LG: Have you spent much time in Italy before? What are you looking forward to doing there?

SP: I lived in Florence until the age of 5. Italian was my first language. Later there was a family house in Tuscany. It’s been decades since I have spent more than a few days there at a time, and then in cities only. Apart from looking forward to being with so many painters, I’m looking forward to three weeks on a hilltop.

I really enjoyed your Paintings, and what you had to say, Susanna. Not sure quite why we have not crossed paths yet. We have things in common. I grew up in The UK and went to art school there in the 70s and 80s., been here for 20 odd years. I hope we can connect at some point.

Best

Andrew Wykes

Andrewwykes.com

Beautiful work. Wonderful feeling g for structure, design, space and color.

I found this very interesting, especially her process of working over reality in so many iterations that the forms enter her head and become abstractions. Thanks!

Thank you Susanna, for sharing your world I really like the flickering line between object and abstraction.

I remember SP working in the print room at the Slade in particular an etching of hers of an armchair– the drawing had a wonderful linear quality.

Thank you Larry. I enjoyed reading your interview with susannah very much, learning about her process and seeing her paintings.

Be well,

Elizabeth O’Reilly