I’m delighted and honored that Susan Lichtman agreed to this telephone interview and thank her greatly for being so generous with her time and attention with sharing thoughts about her art and process.

Susan Lichtman is a well-known and greatly respected figurative painter living in Southeastern, Mass. She is an Associate Professor of Painting at Brandeis University. Select recent shows include: List Gallery, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA, Smith College, Northampton, MA, and has shown at the Gross McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia, PA and the Lenore Gray Gallery, Providence, RI as well as many other venues.

The JSS in Civita, (Civita Castellana, Italy) announced that Susan Lichtman will be the 2016 JSS in Civita Master Class Guest-of–Honor. Ms. Lichtman will be in residence July 11th to August 1st. Here is a link for more information on her workshop in Italy.

Larry Groff: What led you to become a painter?

Susan Lichtman: I started drawing from life in high school. I moved with my parents from New York to the woods of southeastern Massachusetts, and I had a lot of time on my own. When drawing I simply felt most engaged with the world, least bored and most in-sync with passing time. But great paintings made me want to be a painter. I fell in love with all kinds of painting. I went to college knowing I wanted to study art as well as art history and literature.

LG: You studied at Brown University for your undergraduate degree and then went on to Yale for graduate school. What was that like for you?

SL: I have said that being an art major at a liberal arts college affords the slow, scenic route to becoming a painter. Not the most efficient route–progress is slow. But at Brown I read many things I would not have otherwise, was exposed to ideas which I know now have been crucial to my understanding of art. I was a bit of an odd ball at Brown. Most students were interested in abstraction or conceptual art. We all were reading Clement Greenburg.

But for a variety of reasons I wanted to paint from direct observation. One reason was that I come from a family of scientists. I thought at the time that representational painting was more objective, less arbitrary or derivative than other kinds of art making. I went to the Yale Norfolk summer program after my junior year where Andrew Forge and Louis Finkelstein were my teachers. It was the first time I was shown a connection between perceptual painting and the world of ideas. They put together a reading list for the painting students, (Proust, Dostoyevsky, Gombrich etc.) and talked about phenomenology and Cezanne. I felt so inspired and also so terribly deficient–I had so much to learn. I remember coming back from Norfolk and saying that I didn’t want to be an artist–I just wanted to be a painter. Which was funny thing to say at Brown where we didn’t declare majors in any one discipline. But I knew I wanted to commit to this specific niche of art.

I arrived at Yale still anxious and inexperienced. I needed a lot of remedial training. I had great teachers at Yale and made close friends–including my husband Dennis Congdon. At the end of my first difficult semester Dennis gave me very large old stretcher bars used by former students who were abstract painters, and I started making very large paintings of simple studio still life setups. Working large allowed me to work more slowly, and construct a painting without doubting every move. I still prefer to make large paintings–not practical, but it’s the way I compose best.

LG: Who have been some of your biggest influences?

SL: I always painted interior spaces, and am obviously influenced by all the European and American painters of domestic interiors, from the De Hooch and Vermeer, to Hopper and Porter. When I was young I saw the large Vaquez murals by Vuillard in the Petit Palais. I thought they were the most remarkable things I had ever seen. I still love Vuillard and the Nabis, Bonnard and Gwen John.

William Bailey, one of my teachers in graduate school, gave me the confidence to be a figurative painter and to work from life and from the imagination. His interest in literature as a model (and the analogy of painting as a “fiction”) is important to me. It’s helped me come to terms with the issue of realism or naturalism in painting, which I’ve never been able to pull off. I am also influenced by cinematography–the way we experience places in films; scanning and focusing over a duration of time. I want to make paintings that are more like cinematographic passages than like still photographs, where the eye can move around and apprehend things slowly.

LG: I’m curious to hear more about this notion of painting as fiction, especially with regard to William Bailey’s comment.

SL: Bailey once titled a show of paintings–Studio Fictions. I don’t remember him using the word fiction when he taught–but he let us know he was interested in the way painters could invent believable worlds which weren’t completely truthful.

He did encourage figurative painters to work from memory as a way to get to something clearer and more interesting.

Bailey paints his still lifes from memory but these objects do exist. You wouldn’t see the same arrangement on a table that you see in the painting but they might be somewhere nearby. He’s inventing it, describing it as if it were seen from a distance, certainly not the same kind of space you see in a perceptual painting. He also has a body of work that includes figure paintings. Particularly beautiful is a recent series of two women lying on the grass, maybe in homage to Courbet. I don’t know if he used a model for these paintings, but is does it matter? When writers are writing a novel they might base one character partly on their mother and partly on a friend, they’re getting to another kind of truth about their families or the way people interact in the world. It’s not journalism or documentary but it feels real because of the imaginative editing.

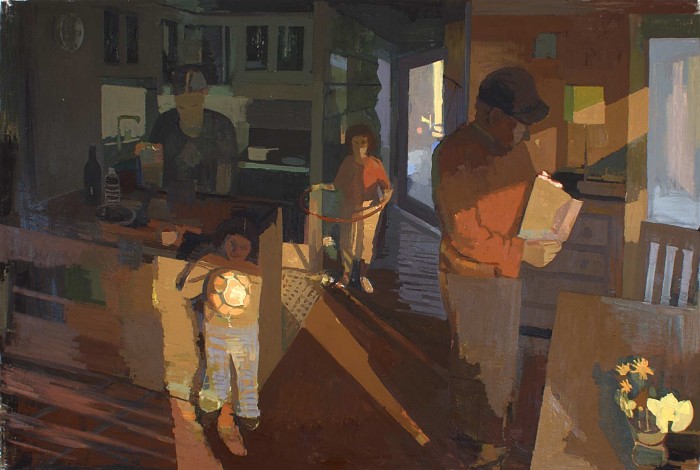

In my painting I would like it to seem plausible that all these people really were at my house at a particular moment with the light just that way, of course it never really happened exactly like that but I want it to feel believable.

I remember when I first started painting I thought that it was remarkable about how Degas could make paintings with lots of figures. How does a painter make a multi-figure painting, especially if the figures are moving? A teacher in a summer course told me it was simply because Degas was a genius. I wasn’t told that he worked from drawings, or from photographs that he took of his models, or how he used the same figure in several different paintings. There wasn’t a lot of talk about his way of composing a picture; how he painted moving figures, something that can’t really be painted from life. I just had to work this out on my own.

At Yale, I took Bailey’s figure painting class, one of the first times I ever painted from the model. He was always showing images of many different artists how one painter worked one way and another person painted it in a totally different way. Of course he was very firm about his belief in certain things, and he gave us a lot of information, but he didn’t think that there was just one way to put your painting together. He talked about how we needed to find our own language; and left a lot for us to figure out by ourselves.

LG: Did you ever have doubts about choosing your life as a painter?

SL: If I had any doubts it would be about other things. Sometimes I wish my husband and I had lived in New York. I think living in an isolated area has been hard at times. But it allowed us to get a lot of work done, grow a lot of flowers and vegetables, and keep a small menagerie of animals, including goats.

LG: Are your works autobiographical in any way? What importance do you give the story in your paintings?

SL: I have been interested in mothers and daughters as characters. I often use a surrogate figure–not me–to represent a mother-type. (A working mother, a housewife, a distracted mother, a glamorous mother, a mother who is domineering or a shadowy presence.) Ultimately though, these mothers relate to me as well as suggesting mothers from myth or literature.

A story gives me motivation, a conceptual justification for making the painting. But I don’t want to give it away too easily. I feel the more I push a narrative the more abstract the painting has to be. I worry about the complex issue of being illustrative. I have always cited the poet Mallarme claiming that the pleasure of poetry lies in evoking, not naming. The painting needs to put forth an event, or an idea, that is purely visual.

LG: How do you go about starting a painting? What can you tell us about your painting process?

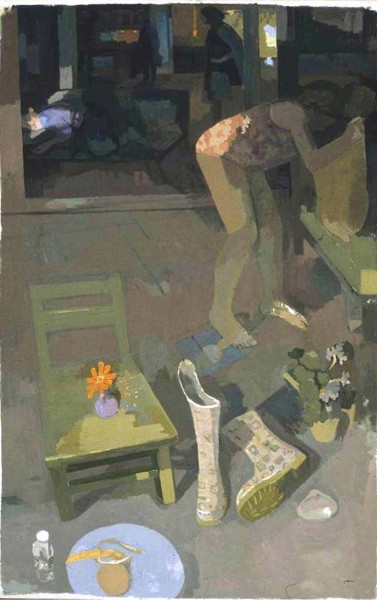

SL: I have a strange method of starting a large painting, but it works for me. I resist the temptation to plan out a composition before hand or to work from a study. Instead I start by painting something small and specific from direct observation, (a vase of flowers or a leg or the shape of a head) somewhere within the rectangle. From there I begin to imagine what might be to the right, left, above and below that thing: another object, a piece of light on the floor, the dog. It’s as if I was zooming out from a close-up of particular form, slowly revealing what might be in the periphery vision. I can only do this with places I know very well, where I know how light falls and how figures interact with things. But the process is totally arbitrary–if I feel like want a piece of yellow, then I put in a daffodil or a lemon, or a yellow dress I saw in a magazine.

Eventually I get enough things down to claim where the depicted image takes place and what is going on. Then there’s a period of editing–taking things out, moving things around. I might make a small painting from the larger painting-in-progress. Maybe things never fit together, or I just don’t believe in the world I’ve made. I might have to put the painting away for a while and come back to it.

LG: It’s interesting that you work from the specific to the general that is so different that what most people learn when first studying painting. I’m curious if you might talk more about what lead you to work this way and what advantages does it offer you? Or what disadvantages do you see?

SL: We’re taught in school to get the color shapes down first and then start to build specificity. However, I’ve had difficulty getting specificity into a painting that was already all laid out. I want the painting to be about the act of looking so I try to start with a focal point of something I’m seeing. Even if I’m working from memory I’m trying to imitate that process of perception where your eyes focus on one thing and then dart around to another object and then meander to focus on something else.

When we see, not everything is given the same amount of attention. We look harder at some things, because of our interest in them. We are more curious about some things and see more information; other things not so much. So specificity fluctuates according to our attention.

When I work this way I find I can get my brush to explore unexpected places like a piece of floor. If my attention moves from say a bowl on a table then slowly to a piece of floor and then move to a leg on the floor that is quickly seen, it’s not so much about painting negative shapes or figure ground relationships. It really becomes more about weaving a fabric of visual moments out of the chaotic ways we look; perhaps walking into a room and first see a bright light on a table, then a couch on the side, a kitchen in the background and then you realize there is a figure in the shadows.

Painting this way reminds me of telling a child a story you make up as you go along, like once upon a time there was this frog and then the frog lived in the woods and then the frog met a fairy… you gradually build a specific structure and before you know it you have a story that can be totally surprising. That’s kind of what I’m doing with this everyday stuff in my house. I think this might be a way that some writers create a narrative–they don’t plan out an entire whole novel before hand. They might start with a character or a particular incident, and then they build the larger structure around that idea. It’s a way of breaking habits of composition or a way to keep from becoming formulaic.

LG: This must involve a lot of revision and need to keep this process very open.

SL: Absolutely, yes; total revision. This process gets me to a structure; the ‘actors’ on this stage get there usually in a way I would never come up with on my own. I take things out and put other things in, shift focus, sometimes making a figure smaller or bigger, I might change the pose or I bring my daughter into the painting, ask her to pose for me after trying to invent a figure based on a photograph or memory. I think that’s what I meant when I said I work from the specific to the general. I start with the specifics but then everything is modified so it finds its place its proper position in the design afterwards. I don’t start with that positioning of shapes; I discover them.

LG: I love it when people shake up the rules for painting. Once you know what you doing and see the painting as a whole; bringing a creative vision and intelligence, you then can paint anyway you want.

SL: Right, as students we learn the importance of designing the whole; how parts can’t be separate, they need to contribute to an organized design. But eventually we find a personal way of building an image that reflects the particular way our mind works.

LG: I understand that you prefer to work from memory and don’t normally work from observation. What are some of your reasons for preferring to work this way?

SL: That’s not exactly true. Every painting has elements that are painted from direct observation–still life elements, a random body part, the view out my studio doors. Figures are usually pieced together from close observation of photographs and drawings. But the whole painting is composed in the studio–just steps from the motif. I feel like I am painting from life, with a slight time delay. I only paint the downstairs of my house and the view from my studio doors. So my motifs are close at hand. I also like to paint things that are moving, transient, in flux. Beams of late afternoon light and walking figures–they would be hard to paint from direct observation, especially on a large canvas. I feel that my work is about perception of a place over a few moments in time. But in order to convey those moments, I have to compose things carefully, and that takes a lot of time, and a process of trial and error.

LG: What can you say about the difference between light in a painting and light in nature?

SL: Well, it’s like the difference between ambient sound and music. I would say that this difference is the most important thing. Light in paintings is where the voice of an artist resides.

LG: You work in a broad open manner using flat shapes of color and you seem to prefer the suggesting form instead of illusionistic, realist form. Has this always been true for you?

SL: Some paintings flaunt their artificiality, the raw material that builds the illusion. You see the symbol at the same time that you see what that symbol represents. I love these paintings. For me it seems the most honest way for me to paint, to make a color shape that asserts itself before it dissolves into meaning–form or light.

LG: Do you still use a limited palette? What are some of its advantages?

SL: Yes. It helps me to glue together complicated compositions. I like economy, when I can get one tone to mean totally different things in different parts of a composition, light here, shadow there. I’m not actually sure what the advantages are of using a huge palette for the kind of symbolic language I use–I know there must be some! I’ll have to research that. One thing I’ve been doing lately is keeping a limited palette as I begin the painting, then at some point late on inserting something totally new. For example, with a red, black, yellow, white palette, inserting something blue-hued after a time. It glows.

LG: You also have made small works on panels with more matte mediums such as casein and gouache. I’m curious, this seems similar to the distemper Vuillard used, who often painted in this “a la colle” manner, a much slower, difficult and less convenient approach. Jacques Salomon, Vuillard’s nephew said that: “…not only did Vuillard prize the matte tones obtained by this method of painting, he considered that this refractory process helped him to keep his excessive facility under control, and allowed him to deliberate more fully over his work, if only during the pauses when his colors were drying.”

Is keeping your facility under wraps a concern for you? Why would that be important for a painter to think about?

SL: Such an interesting story about Vuillard. I do think I find the matte surface of casein and gouache beautiful because it reminds me of his distemper, as well as fresco. But my reason for using it is totally the opposite of Vuillard. The quick drying paint allows me to make many changes quickly. Lately I’ve been using acrylic gouache for the small paintings, and sometimes I will make the paintings with one brush–a #4 round watercolor brush- and just repaint quickly and obsessively until I get what I want. I will change the tone and drawing of a shape over and over. The paint gets crustier, but I don’t get the mess I would get with that kind indecision in oil paint.

But getting back to the idea of facility–yes, slowing down and finding more contemplated forms is an important thing for all artists to think about. The first solution, the obvious solution, is not always the one that endures. Some painters I admire do work on one-sitting paintings, but I think they arrive at the easel well prepared for the performance.

LG: I loved what you said in the 2008 article in American Artist that; “To me, close-valued color is magical. It’s a way for the paint to imply the fiction of light and air. A palette of close values also gives the picture a kind of envelope into which everything is placed.” Can you share some more thoughts about this?

SL: Close valued color creates a sense of distance, as if atmospheric perspective was applied to things close at hand. I have liked this sense of distance, especially when painting my own home and family, as a way to avoid sentimentality. Now I am trying to use blacks and whites in my paintings and everything in between. I might hide important things, (figures) in close value passages, and use vivid contrast where nothing much is happening, making pictorial “red herrings.

LG: I’m intrigued by the notion of pictorial “red herrings”; can you further explain what you mean here?

SL: The perceptual experience of reading the painting considers that we are phototrophic, that we move toward light; ultimately, though, we are most interested in looking at people. If you play a little balancing act between elements of light and bright color and the pool of figuration you slow up the reading of a painting. A red herring is a distraction from the central, important elements of a picture. I often don’t want the figures to reveal themselves too quickly. Of course there are many ways to paint, but I love paintings where the figures are revealed slowly, for example, in Bonnard’s pictures figures emerge gradually, maybe not seen at first, as they are woven to the wallpaper or background. Rembrandt often put the eyes in the shadow and places the light somewhere else, like on a shoulder–that brilliant light redirects the eye, it is placed somewhere where it isn’t actually important and then only after a while do you discover the eyes, the windows of the soul, and all the humanity they contain. You’re playing with the weight of perception.

I’m frustrated by people who just glance at a painting, especially a representational painting, to identify what particular thing the painting depicts. I want to make it more difficult to read, to slow it down, so that’s what those red herrings are for. You go to all these different places before you get to girl in the chair. I think I’ve always wanted to make slow paintings, to make images that unfold slowly over time.

LG: You will be the guest of honor and teaching the master class workshop at the JSS summer program in Civita Castellana. Have you spent much time in Italy before?

SL: I am so looking forward to the summer at JSS! I have been to Italy many times and always find something new there.

The great thing about being in Italy is that you can’t see anything comparable in this country; like seeing the Piero frescoes in Arezzo, Monterchi, and Sansepolcro. Or the Giottos in Assisi or ancient frescoes in Pompeii, just fabulous. I can see how the Renaissance painting spoke to that tradition of wall painting from Pompeii’s Villa of Mysteries. I love the way you can experience a wall painting not just with the eye, but with the body first, as it is a part of architecture, a surface. You have a similar physical relationship that you might get in front of great abstract paintings. And it’s incredibly inspiring to see the sculpture from antiquity and the Renaissance that is everywhere in Italy. Figurative sculpture is a thing that sits between life and drawing, it occupies our space, but it is also expressively coherent, full of information for painters.

This is a wonderful interview with so many insights into Susan’s work and motivations. I was particularly fascinated by her method of starting a large canvas, by choosing one object then more or less inventing the interior as she goes. Her mentioning of this “phototropic penchant” in us or the viewer, which is to go toward the light area of a painting was also interesting. And the aspect about having her figures reveal themselves slowly, rather than blatantly had appeal as well. I liked the comparison to Rembrandt and how his figurative works functioned in a similar way with the eyes and character of his subjects revealing themselves slowly. I was also taken by her observations of Villa of the Mysteries Frescos in Pompeii and Piero’s work in Arezzo, which I have visited as well. And finally the close-value discussion was intriguing as well. So, thanks so much for sharing this interview and Susan’s thoughts.

i am extremely enjoy Susan Lichman thought and her painting thank you

wonderful interview and examples. I particularly like this idea of slowing down and the search to discover method. That aspect has shown me how to talk about my own work and what can be found by looking rather than skimming the surface and naming something ‘in the style of …’

Thank you for arranging this interview. This is actually my first time seeing Susan Lichtman’s work. Wonderful. I especially appreciated her sharing William Bailey’s thoughts on painting as fiction 🙂

Great interviews. Esp. with Ann Gale and Susan Lichtman. Now interview Ruth Miller Forge!

Thanks for sharing this wonderfully inspiring and informative interview. Susan’s paintings and clear thoughts are inspirational

This is what I tell myself when I draw : Know what you want us to look at, and to see when we look at your painting, or photograph = know what you are going to ” point at ” in the painting – what is inspiring you to paint this particular picture. If you point at too many things, in no particular order, showing that there isn’t a real focus for the picture, you create an equivalency, and thereby lose your viewer’s attention. Cezanne saw painting as an ordering of things, as ” organization.” The painter orchestrates things in his or her painting to make for a compelling result.The things, (which may include pieces of light, ) must be compelling to look at. Use the means at your disposal to direct your audience to see what you are seeing, as a unified whole.

I noticed a few things. The construction of the paintings remind me of putting together a puzzle. large shapes are broken-down by color which create movement, and motion. This adds to the impact the protagonist play in how I read the entire scenario.