Part Two of Three – On Teaching.

Please see part one for the general introduction and to read part one.

You can listen to the part two audio podcast – either streaming or downloaded to your computer from the links below.

Link to the page where you can download the podcast to your computer, https://archive.org/details/ssPartTwoAll

The play control below is for the streaming version of the audio

Larry Groff:

Has your teaching changed in response to your evolution from painting outdoors to your current studio-based more abstracted works? ?

Stuart Shils: The way I approach my classes has never been about my own work, that’s the last thing I want or need to talk about.

But paradoxically, or maybe not, as my interests have evolved, I mean as the focus of my work has become less overtly representational, my intention as a teacher or guide, has become even more concerned with close looking and analytical observation. And that doesn’t mean realism or being a perceptual painter, but rather, with looking closely not only at nature, but as much at the work being made in response.

But isn’t it all about looking closely anyway, regardless of representational or not? And what is representation? Representation of what, I mean, just what are we re-presenting? When I look at something–a landscape or a person and register an observation optically, I have to then turn back to the working surface, the paper, paint or whatever, and there is an interval of time in there during the turning back, so in a way, isn’t it all a dream or a memory? And that’s why I ask, what are we representing?

So yes, my work for the most part no longer necessarily looks like ‘landscape’ per se

and in the classes I’m not trying to show anyone or teach anyone how to be me, that would be so beside the point and so disingenuous. And anyway, I’ve never really known who me was or is.

Rather, the emphasis is on being alert and present visually, focusing on the cultivation of attention to what is happening within the parenthetical enclosure of the moment.

It’s what I call the perceptual moment, and this has nothing at all to do with that group in America called Perceptual Painters.

The perceptual moment that I’m talking about here is not about the appearance of your work, or if you are riffing on Antonio Lopez, or if you went to PAFA and work naturalistically, or if you use your little finger to blur edges.

Rather it is about being acutely aware of the interiority or dimensionality of your own observation and response. In other words, how you perceive and then shape a response to what is out there. I also think of that moment as ‘the visual kiss’, that fleeting but extended moment of connection in which you recognize that perceptually (and conceptually) when you are looking at something and acknowledging the possibilities within that engagement, that there is a beginning and an end. And that between those two points there are tough decisions to be made about structure and limitations, and as the reader of and shaper of that moment you are also an editor, and you can’t take or have everything that you see.

Extending the kiss analogy, another way of describing navigating within the moment of concentration, or not, is if say you are sitting in a café early one morning under a romantic spell and you are kissing your friend and at the same time you are looking over there and thinking, ‘hmm, I wonder where that person across the room got that cool shirt?, then where are you, I mean, are you really rooted in your concentration? You’re neither here nor there. It’s like Lawrence Ferlinghetti said some years ago in an interview in the Sunday Times magazine section with regard to the Internet ‘…if you’re everywhere all at once then you’re nowhere at all.’

I’m slightly paraphrasing but it’s something like that and you get the picture. And it’s very related to the mechanics of our own visual experience and this is something I’m trying to address in my classes, a clarification of intention and establishing the idea of a perceptual hierarchy.

Larry Groff

Some of your workshops you have students use less common materials like crayons and cut-paper. How could this help a student to paint better landscapes or still life?

Stuart Shils:

PLAY and curiosity are of huge interest to me in my working life and in my classes, and that quote by Guston always comes to mind: “What I mean is that the serious play, which we call art, can’t be stamped. I mean, you have to keep learning how to play in new ways all the time’.

That notion of play is so relevant to not only looking out at nature, but also with regard to how we look back at the art we admire and dwell on from the past and draw into our own thoughts. For me one way of doing that is posing questions using materials other than those used to make the work itself.

Questions of visual inquiry can really only be made with materials in hand, not as abstract ideas using words, and the more ways we have of developing that improvisational visual language of questioning what is there and what it means to us, the better.

A few years ago I was doing a semester long life class at PAFA in Philadelphia, and watched students who had gone through the conventional life classes, now in their 2nd or 3rd years, leaping into speculative forays in front of the model, sitting and using crayons in such high minded yet playful ways because those casual materials and the spirit of the materials gave them much needed permission to explore and play in ways that were not maybe possible when the ‘rules’ sat on their shoulders like mother superior parrots talking about Degas and Dickinson and the old masters and how they ‘did it’ and the right way vs the wrong way.

So with the use of less common materials, I’m hoping to interrupt assumed or inherited ways of visual thinking and encouraging participants to reconsider what they are doing and how they are doing it. Oil paint is only one way of making an image. And even if you are using paint, you don’t need anything precious, expensive or hand ground imported from England. I’d rather have students working with buckets of mud and spaghetti mops than with expensive artisanal paint.

If the ‘old masters’ came back to life, they would not be using silver point or dark grounds necessarily, right? Now we use magic markers, blue tape, and Ipads as in the case of David Hockney who has been a great pioneer with playing around with new materials and digging into visual curiosity and a great example for us of how an artist grows into ones’ own time. And Frank Auerbach draws with markers. Remember, that Eakins, who now probably feels like a faded old man to hipsters, worked with Muybridge in Philadelphia and that at the time was really cutting edge application of contemporary technology.

Larry Groff

What are some of your most important lessons that you try to get across in your workshops?

Stuart Shils:

In my classes we’re addressing two primary categories of visual thought: how we see when looking ‘out’ at the world and then what we do with that graphically, and what I mean by that is, how do we make sense of the way we see the three dimensional world translated onto a two dimensional surface.

And keep in mind that the resulting image doesn’t have to be a faithful, honest or legalistic transcription of what is actually there, as much as a record of your process of interpretation, the evidence of your wrestling with possibilities for structuring the narrative of your visual desires, of course, very related to the so called facts (as comprehended subjectively) of what it is going on within a moment of contact.

And it’s not just a matter of ‘composition” in the conventional sense of making an order of flat puzzle pieces on a surface, but of also making decisions about an order that assumes a quality of hierarchy revealing variations of emphasis because everything cannot be seen at once nor therefore delivered graphically at the same speed. All graphic decision making is rooted in HOW we see, and in how we make sense of what is in front of us, and by determining very early on what I call the crux: that unique intersection of events, almost like a temporary perceptual architecture in which all things are contributing a role, but are not equal.

People who have taken one of my classes have heard this story, and the idea within it sits for me as the foundation, the place of beginning, and it’s probably THE most important thing that I learned while formally in school.

Before I went to The Academy (the school that is now called PAFA), I took classes for about a year and a half or maybe a little bit more, in the mid 1970’s, at what was then called PCA (Philadelphia College of Art), now known as University of the Arts. And these classes were not in the so-called Fine Arts, but in the Commercial Arts: packaging design, typography, etc. And there was one class in Magic Marker Markup, to teach people who would work in ad agencies how to do very abstract thumbnail mock up drawings using markers.

For instance, if you were manufacturing Cornflakes commercially and approached an Advertising agency for an ad design, and you’re talking to the Art Director and describing the mood that you want – maybe a kitchen table in front of an open sunny window on a yellow wall, with a bowl of cereal on the table cloth next to a slice of cantaloupe on a plate and a few napkins nearby – she calls in a person who specializes in marker markup which is really the first stage for defining the visual concept, and you all speculate about what the image could look like. And that person goes back to her office and puts together some abstract compositions in color but that also say a lot about the particulars of design that would lead to a photo shoot.

And so my teacher was a person who worked professionally in this business, and the first night of class he told us something that hit at the time like a ton of bricks and that I never really forgot and, that provided me with a kind of critical insight into what the visual world was about. And I never would never have expected that to come from a commercial art class.

He said, “Look guys, your first line of responsibility for developing your eye, is to learn how, wherever you’re standing or sitting, to build the visual and analytical muscles for being able in the moment, to immediately identify and seize the specific and particular relationships of all the individual parts, all the shapes and the sizes of the shapes that happen to be in front of you that make that place uniquely what it is as a unity of form.

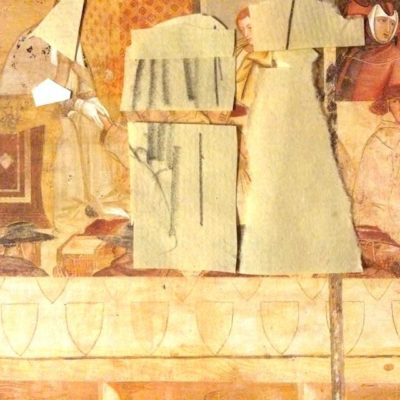

(And as a tangential point, it’s the same with looking at paintings, I mean for us to understand how they are made in terms of their formal design. Look for instance at this Fra Angelico and think about the component parts – the sizes and shapes of the lights and darks and what they are as colors and, how they sit in inter relationship to each other and what you see first, and then second, and how the pathways of light and dark carry our eye through the very active narrative of form.)

Anyway, getting back to that class, he was talking about cultivating an analytical musculature to immediately size things up, to hammer into place in the moment, an understanding of the proportional relationships of everything before your eye, as you are making your way through the day. Not just in the studio or when you are seriously ‘at work’, but as a way of life, all the time.

That seemed like a pretty big deal because it pinned down for me the critical importance of that initial moment of contact and, the need to hold onto it tightly, before the verbal/intellectual mind throws a tidal wave of erosive and distracting information across the road. It suggested a way of beginning to clarify one’s position, taking stock of possibilities, and pining down a kind of visual intention before even touching the brush.

Larry Groff

What are the benefits, as well as the dangers, from painting from observation?

Stuart Shils:

The benefits and dangers of painting from observation? There are benefits and dangers to everything, but for me, observation (and that can mean many things), is really THE fundamental starting point, the place from which many directions of visual thought radiate, and really, the beginning of a huge conversation.

There’s a danger to everything: you could go out on the street for a smoke while taking a studio break and get run over by a car, or you could be rejected by a gallery who tells you they’re not interested in your paintings.

Or, wonderful things can happen. You can wake up one day and understand that rain is not a yucky or inconvenient material, but a sensuous color presence that you can wrap yourself around and it around you. Or you can walk outside at night and realize that the sky is not just something up there, but rather a palpably sexy, fabric like airspace.

So working from observation is both fraught with peril and full of fertile opportunity and how you use it is largely a matter of who you are or who you want to be and, how you place yourself conceptually within a broader culture conversation.

If you get involved with things like the Plein-Air movement (which is not at all the same as being an outdoor painter) then you’re going to possibly be engaging in risky behavior. On the other hand, if you look at the drawings of Emily Nelligan you might think, jeeez, how is it that my eyes are being given a new lease on life from pieces of paper 8 ½ x 11 inches covered in varying weights of charcoal?

The point of observation, is exposure to vulnerability, I mean, putting yourself in a situation that involves cultivating a state of presence within which you cannot simply impose a prepackaged idea of what ‘finish’ means, and instead deal with what is being thrown at you that may very much disrupt or contradict what you want to be happening or what you think ‘finish’ is supposed to be, and that is a good thing.

And a painter whose work I hugely admire comes to mind, with regard to vulnerability and the constant improvisational struggle to make sense observationally with what one is parked in front of: the work of Stanley Lewis, who canvases have always astonished my eyes and senses. And he feels like an artist living in a state of ongoing vulnerability, which to me, means honesty.

The school I work at in Philadelphia (PAFA), has for a very long time expected and required students to engage intensely with observation in the first two years and that is intended as one way of waking them up visually, but ultimately how they use that is up to each of them.

Working from observation doesn’t have anything to do with old master schtick, good manners, trompe l’oeil nor conservatism. It does not mean feeling sympathetic with the Florence Academy, nor with the Neo Classical Academies all over America. Rather, it’s about being alert and slowing down long enough to notice what’s in front of your eyes and dealing interpretively with qualities of relationships that exist in nature. And by nature I don’t mean pretty or cute places or Sierra Club calendar images; instead I mean anything we see with our eyes.

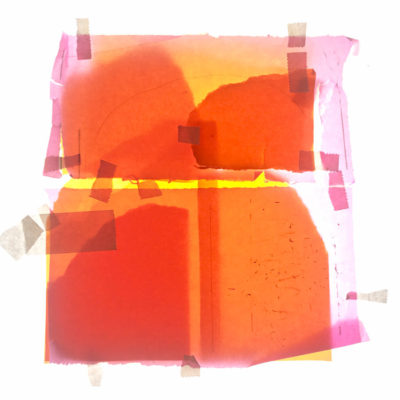

I hugely admire and respect the work of the English artist Francis Davison and a piece like this

says to me more about landscape and immersion in observation of landscape than most ‘landscape’ paintings one sees around. His work always feels as if he was in very close emotional communion with the Cornish landscape where he lived.

(NOTE: youtube video links about Francis Davison –

https://youtu.be/uj0GR5PRaNg

–https://youtu.be/s47YpqT92wA)

And I have always felt that the small woven Minimes of Sheila Hicks, with their hypnotically narrative text like organization of strands and knots are hugely observational in the sense that they feel like an extended harvest of ongoing attention to the physical or material world, from an artist who is alert to the visual and emotional presence of many things and to many qualities of encounter.

Similarly, I find the three dimensional/sculptural work of my friend Greg Biche, a young artist from Philadelphia, to be more captivating in its sense of form and qualities of observation than the work of many people who go outside and paint buildings in the city, and his blocks sculpture which is certainly also painting but in three dimensional form, feels drawn from an astute sense of looking closely at the surrounding world. Where else does such a sense of intimacy and scale come from?

Observation is for me ultimately the beginning of feeling and the beginning of learning to feel. When we look at something closely, be it a painting or nature, it’s not a superficial business, but rather a total commitment to being there, and if we can be vulnerable, we are taken into the complex interiority of that moment.

I always tell students that I can’t teach them how to feel, that has to come from their connectedness to life experience and for that they have to fall in love or go up on the roof at night and cut open a cantaloupe and look at the color, or run on the beach during a snowstorm. But, if we immerse ourselves in the careful process of tasting and taking notice, meaning, the constant analytical examination of how and what we are seeing and taking account of that with our senses, then step by step, that process brings us closer to a place of feeling.

a refreshing and inspiring read. thank you so much Many of these works are great!