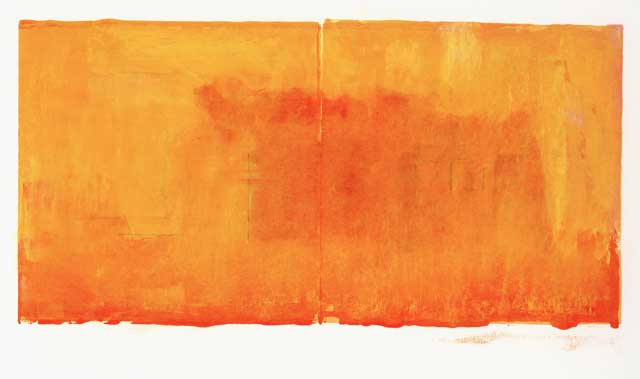

Stuart Shils, While Walking around Tel Aviv on the Way to the Arlozoroff Bus Station, Monotype 5 1/4 x 10 inches, 2010

Stuart Shils currently has a show called Monotypes and Photographs at Davis and Langdale. The show is up from March 19 to April 23 and really worth a visit if you’re in the New York area. As some readers may be aware there is a video of Mr. Shils creating a monotype that may inform the current body of work. (see the video below the fold)

Mr. Shils has been gracious enough to answer a few questions from Neil Plotkin about this current body of work on paper. Stuart Shils is also giving a 3 day workshop in San Diego, April 28 through May 1, 2011, organized by Painting Perceptions. There are still a couple of openings for anyone interested. Details about the workshop can be found at this link. Also Stuart Shils is giving a Lecture and Slide Presentation titled “The Perceptual Moment: The Nature of Perception and The Perception of Nature” at San Diego’s Museum of the Living Artist in Balboa Park. April 28, 2011, 6:30 p.m. This talk is free and open to the public.

Neil Plotkin: Can you pick one of the prints from this show and walk us through the way that the image developed from beginning to end.

Stuart Shils: Let’s talk about two different monotypes, because they would demonstrate different aspects of the same process. In the catalog, the second monotype that’s called Near Union Square was made before the summer and my last trip to Italy.

Near Union Square from the 20th Floor, in the Distance

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 x 10 inches, 2010

(click for larger view – true for all the images in this article

SS: I had a very good friend who lived near Union Square and I used to stay at his apartment for many years before he died. I spent a lot of time at his windows just looking out, and occasionally would make line drawings and took a lot of photographs.

I remember at one point on the left side of this monotype, that white building in the bottom right corner, went all the way up to the top on the left. After the first week I looked at this and decided the sky, that blue, had to come down, that the white shape that was the building that went all the way up the side had to be radically altered.

And to varying degrees, the same thing is happening all across the image. Major changes were occurring the first, second, third, fourth, fifth days, or even a week later. I simply don’t trust my initial judgment anymore as far as being able to achieve some kind of resolution or some kind of understanding quickly.

All those little touches, all of the modifications and adjustments have happened over time, the time that is necessary to get enough distance on them to see what they are beyond my initial expectations. Over the course of several weeks, I might have one or two dozen of these going…

NP: Of the same image…

SS: No, all of different images… like this one called Sun Passing Quickly on Lower West Side. These images are made in clusters.

The very heated up Italian ones are similar. Some of these were made just before I went to Israel in December, and some were made just after I returned. I realized I had to close the chapter; I had to close the book on these. I went back to the ones that I had made in early December and worked on them a little bit more. I did a new set of these very hot Italian ones. I finished them and made a few more in mid-January.

I’ve been home from Italy since the beginning of September, so these images, these residues, are distillations of memory that can only come with time. Unlike working directly in nature, maybe what monotypes offered me, from the beginning, was a way of reflecting on an aspect that was and is absolutely impossible to approach or to understand sitting in front of nature. And actually, the interrelationship between those two things is very complex.

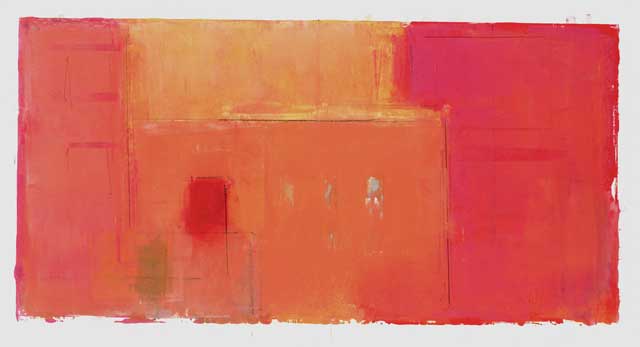

Remember that very heated up image we were talking about a minute ago [This was mentioned prior to the interview]? It’s called Walls and Rooftops in Volpaia, After Prosecco. That was done in mid-January, months after I had been away from that place; yet my feeling is that somehow, out of the entire collection of Italian monotypes, that is the nail in the wall. That piece for me is like the arrow that hit the bull’s-eye, the culmination of the summer.

Walls and Rooftops in Volpaia, after Prosecco

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 7/16 x 10 1/8 inches, 2011

For me, this was an image done in an extreme state of visual passion, totally rooted in memory and far from the place, yet in some way extremely connected to particularity.

NP: Would you say that the difference between the paintings and the monotypes is that you’re sitting in front of one, and with the other you’re distilling time?

SS: That’s one difference. In the last number of years, I haven’t really gone outside that much, except in the summers. I did for many years, for 25 years I only worked outside and this difference is a place I’m sort of wrestling with.

My studio is currently filled with very large – very large for me – 40 and 60-inch horizontal paintings, images that look like this yellow and orange monotype that we’re talking about. These are oil paintings I started in October. I then spent the entire fall and winter traveling, with only being able to work on them intermittently, so I’m just returning to them now.

These oil paintings are done in colors that bear no resemblance to any outdoor paintings that I’ve ever made – I decided to make paintings that were in and of the spirit and practice of my monotypes. I thought, at last, that I was going to paint on canvases the way that I make the monotypes, basically just making it all up, invention rooted in reconstruction of memory. None of the monotypes are made in front of nature; they’re made in front of memory, reinforced by the particularity of drawing, and by the absorption of a tremendous amount of sensory information. But it’s not as if I never went outside in my life to look at anything.

This is really the big challenge to me now, how to go about this in painting, but it is an issue totally rooted in the making of monotypes. When I was moving my studio recently, I rediscovered the very first black and white monotypes I made in Ireland, in the studio over there, not in front of nature, in 1998.

I began exploring monotypes because I was spending all this time outside in Ireland in the middle of the night between midnight and three. The sky and the ocean at night with the moving clouds and mist were unbelievable, really took my head into places that it had never gone. I also spent a lot of time outside in the rain, but you couldn’t really paint in the rain, of course. And I remembered that years before, maybe 1992, my friend Bill Scott had seen some nocturnal paintings I had made in the city and he said, “Oh, you should make monotypes.” So this idea was in my head, just took a while to come out.

So I came home to America, away from that summer in 1998, and started making monotypes in the studio to unearth and define the range of sensory experiences that I was engaged with in Ireland but had been unable to paint. So recently when I was moving I found these earliest monotypes, and I was stunned because they seemed to resonate so true. But I remember when I made them, everybody went, “Ha, ha, ha, this is a bunch of bullshit.” They were so different from who I had been as a painter.

That was the whole problem with what happened in Ireland to begin with. The sorts of paintings that emerged there, after the first four or five summers, were so distinctively different than who and what I had been visually, people began to flip out and I began to retreat into my work self protectively, it was a very problematic time.

So my paintings were veering off. I was catching a lot of flak from dealers and collectors who felt I had betrayed something by changing. But the messages coming from exposure to nature were clear and I threw myself deeper and deeper into trying to figure out what this place was I was at and what it was all about. And I did that with monotypes as much as with oil painting.

The interrelationship between the paintings and the monotypes is a critical one. In the last couple of Italian visits, and the completely different exposure to the kind of color that Italy has incited in my head, it’s created an explosion. But it took three years for Italy to really hit in that way, and any number of experiences I had this past summer with the color and the mood and the infectious saturation of everything, whow, it all really hit. That monotype we were looking at with the horizontal orange and yellow melting air and building couldn’t have been made three years ago, because I didn’t understand that visual and felt place with that kind of connection or depth.

When I came home this past September, I embarked on a set of oil paintings in the studio that were in no way related to any direct, note to note, outdoor experience. I was going to try in paint, to explore what had been a gradually encroaching process in the monotypes over the last years. I was determined to try and force the issue, and see if I could paint completely in the spirit of how I made the monotypes and just let myself go, like letting the kite out on the string and see what happens, instead of worrying about what it was supposed to look like or what someone else wanted it to look like.

I kept asking myself if I could make these monotypes, why can’t I make paintings like these? It was a matter of whether I was going to be able to banish the voices from my head in the studio that prevented this from happening on canvas. The voices that came from people out there in the world, who knew my work and had some ideas about what they wanted to happen, “No, don’t do that, nobody is going to buy them.” One must never let those people into the studio.

Naples Walls in Late Afternoon Heat

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 10 1/8 inches, 2011

NP: You’re talking about how you had the freedom to do these experiments on the monotypes, yet didn’t feel that freedom with the painting. Why do you think that the monotypes allowed you that freedom whereas the painting did not? Is it a scale issue? Is it a canvas issue? Is it an audience issue?

SS: I feel extremely comfortable working on paper. Whether it’s drawing with oil pastel or drawing with pencil or making monotypes, there’s something extremely familiar and familial and comfortable about working on paper. I’m not saying it’s easy by any stretch of the imagination. It’s more like drawing blood.

There’s something about the self-consciousness of oil painting. When I am working with paper, I enjoy the experience I have with my studio and my work. In addition, the gallery that represents my work with paper [Davis and Langdale] doesn’t give me a hard time about what I do. They love what I do and have always been that way.

I had been trained as a painter to think that the only paintings that matter were the ones you make while you’re looking at something. I thought that was Gospel. When I first started making the monotypes in 1998, I was amazed to see what can happen with the back turned to nature. But what does looking at something really mean? If I’m sitting in a landscape or urban space and I turn my head to look at something, and then back at the canvas to paint, I’m no longer looking at anything, right?

So what’s the difference between that and going to Italy, or going to a friend’s apartment downtown in New York, and making a drawing; then three months later making a monotype? The interval of separation is different. If I’m out there looking at something, and I turn my head to look at the canvas, what’s the interval? Two seconds as opposed to three months? What’s the difference? It’s the difference between Beaujolais Nouveau and Bourdeaux. Who wants to drink Beaujolais Nouveau all the time?

With time, things happen, and this is the paradox that I’m trying to figure out. Why is this orange and yellow monotype we are looking at from Italy a definitive realization of a place when it was done four-and-a-half months after I was at the place? I’m trying to figure this out and understand what it means in terms of working process.

The answer is revealing itself with time. The monotypes placed the bar for me in terms of reestablishing a different sort of ambition for making paintings. If I could do these, then why couldn’t I do this with painting? That’s what I’m trying to figure out in the studio.

The Same Place Near Padova, but with Clean Air

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 10 1/8 inches, 2011

NP: You do so much teaching with students in workshops. Obviously this takes a great deal of your time and a great deal of your energy. You have to be getting something from this, as well. What are you getting out of the teaching?

SS: If I had started doing this twenty-five years ago, I’d probably be bitter and worn out. But I didn’t do that. I didn’t really start teaching until I was older. My own teachers didn’t start teaching until they were in their forties or older, so the model for me was this was always something I would do when I was older.

First of all, I don’t have any degrees, neither a BFA or a BA or a master’s degree. I went to school for a very long time, but no degrees. So when I did apply for jobs early on, the application or letter got thrown into the trash, I was not a member of the club. But more importantly, the larger message was clear to me from the beginning, that I wasn’t going to even open my mouth before it was the right time and my own teachers let me know this.

I put that off for as long as possible because I didn’t have anything to say or anything to talk about. I mean, what was I going to teach? Was I going to get out of school and just begin repeating all that I knew, the words of my own teachers? I did have this sense that I needed to go out and do something.

I started teaching workshops and master classes about 2001 and I was out of school for 19 years. That was the year of 9/11, and I really began doing this in response to the beginning of the collapse of the marketplace. I began to realize with 9/11 that the ground that I had been standing on for the last ten years was extremely fragile, and that it was very possible that there were going to be big changes going on here in terms of the market place.

And it was occurring to me that I really disliked certain aspects of exhibiting to survive and depending on sales, and that this is something that maybe I wanted to partially get away from. There were years in the nineties when I was doing like four and five shows a year in different places, and it was beginning to make me insane.

So with the impact of 9/11 and then the collapse of Silicon Valley in 2003, I became concerned about the long term economic prospects in combination with being fed up with the kinds of relationships I had with some galleries. I began to explore teaching both as a source of income and also as a source of renewal, of hope, as something related to the positive aspects of work, away from all the nonsense that can come with the market place.

And I began to really enjoy the conversations I was having with people young and old. At the beginning I was teaching a lot of Continuing Education, and I thought that was fantastic, because the paths and stories of older people are so much different than the typical art students, nineteen, twenty and twenty-one year olds.

I discovered fairly quickly that all these people, regardless of age, were actually my teachers and that I could learn much from listening to their questions and trying to figure out how to formulate responses. Also, as is the case with my young students, their perception of the world is very refreshing and I depend in a way for them to introduce my eyes to new work. The educational dialogue became a great source of interest.

It’s wonderful. I love it. And of course it’s an enormous compromise of studio time; but should if I die tomorrow, it’s not like I’m going to regret having spent twenty-five years in faculty meetings, I’ve done a lot of my own work over these years.

The frustrating this is, that I feel like I haven’t even started to paint; in a sense, and that everything I’ve done is just like Vorspeise, the appetizer. This is a terrifying prospect now, because my time is so eroded by responsibility that I don’t know if I’m even going to have time to do the work I want to do. So I’m watching myself age and thinking, how much time do I have?

I was recently remembering what a fantastic thing it was to have a summer to just work with no responsibility. When I go to Italy, there’s a school there. And I do love that, they’re wonderful students and it’s fantastic to be engaged. But to have the isolation of week after week to sink into oneself as I did on the Irish coast for 13 summers, to be able to absorb the place, to not have to go to dinner at a certain time, to be able to stay up until three o’clock in the morning and not have to worry about anybody or anything, that experience might be gone. I might never again have that enormous purity of painting time.

Should that be the case, that’s the way it goes. I’m just dealing with what I have and trying to be happy with that. I certainly don’t regret this business of contact with people, and working as a teacher. I’m actually learning from it, so I get a lot back.

There were two other things I forgot to say, but meant to say about teaching:

1) That it seems, in a way, at this point in my life, teaching seems like an obligation, a closing of the circle. I was very, very lucky to have had 4 extremely influential teachers, without whom I would be nothing: Doris Staffel, Francis Tucker, Arthur de Costa and Seymour Remenick. (Ok, there are in a way, other people from whom I have learned a lot but these were my formative and formal teachers early on.). I’m not sure if my sense of obligation is to them or to my students but either way I feel like I am some kind of link in a chain and I really have no choice.

2) From the process of having to talk, to put things into words that don’t easily exist in words and, from listening to them, I really learn as much if not more than the students do. Remember, we are always learning and I feel like I am searching and trying to figure things out as much as they are.

Bright Sky, All Sorts of Buildings Under the Cloak of Smashing Light

Monotype

NP: I know you talked about this a little bit. During the printing process, do you go back and forth? If things don’t go well, do you completely print blank over a print? It brings up the question of how these things are different. When you’re working with a brush, you’re literally painting it onto the plate. Do you see them as different, other than it’s printed on the paper?

SS: Well, yes. They’re very different insofar as they’re all done in the studio. And that’s a big, big difference. All summer I painted outside in Italy, but the thing about painting outside, and the thing about painting in front of nature is that it’s a long and gradual process, and I realized years ago that there is an enormous range of malleability and one needs a lot of time for it to evolve into things that cannot even be imagined.

As a student, you start with a certain kind of idea of verisimilitude and painting what’s there. Over time, painting what’s there shifted for me into trying to respond to my internal meter flickering back and forth; the little meter inside that was more about painting how I feel in response.

For me the monotype has posed very serious questions about painting, about how to make a painting or, what the painting is supposed to be. Not the way I was making paintings ten years ago, sitting in front of something and responding to it, but working away from the direct contact; whether it be through drawing, through memory, through some kind of interpretative reference to a photograph. Constructing a painting in the studio that carries and reeks of the best aspects of what happens through the filter of distance and time is simply not the same as what happens when the thing is right there literally before the eyes. Yet at the same time, who is to say that even when we are outside working that we are painting what we see? Right?, the real question is not what do we see anyway, but how do we see and what is our responsibility to it in terms of what we make of it within our work?

What’s accessible in the studio is not accessible out of doors and the difference is critical. This is a process that can only be shaped away from the facts of nature; and in a way, both contact with nature and that distance away from nature has set the bar of expectation, which for me is to graft the spirit of the monotypes into the paintings.

Painting Perceptions would like to express thanks to Neil Plotkin and to Stuart Shils for their time and efforts with this interview.

Summertime in Rome, Just above Trastevere

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 10 inches, 2010

Walls on the Edge of Montalcino, Very Late Afternoon

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 10 inches (image)

Executed in 2011

Sun Passing Quickly on Lower West Side Buildings, NY

Monotype: charbonnel etching ink, oil pastel and graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 10 1/16 inches (image)

Larry, I loved the video of Stuart Shils making a monotype. His engagement with the paint was so inspiring. It just made me want to run to the studio! Thanks for making it and for sharing it with us.

Thanks Neil and Larry! Stuart sent me a catalogue from the show, and I have been drooling over it since I received it. I love the new titles, how they explain so very much the “way” the prints/paintings came to happen. It makes them feel even more intimate in a way, a peek into his notebook. Luscious paint too. I can also sense a new frontier about them, and so it is so rewarding to read his thoughts about the new works here.

Nancy, Good to hear from you and I’m glad you liked the interview and video. However, so there is no confusion – I didn’t make the video, that was made by Stuart and a friend who initially put it up on YouTube – I’m just re-posting the video here. Neil Plotkin made the interview for Painting Perceptions. I bet Rob Moore (one of our former teachers at Mass Art, would have loved Stuart’s paintings…)

Rebecca, Thanks for your comment and I agree with what you said about his new titles. I’d love to see this show. I’m very curious to see how and where this evolution leads.

Thanks , I enjoyed this a lot!

than you so much Larry, that was a pure pleasure. I was standing up the entire time! haa! I sort of froze and wouldn’t stop reading while holding my computer!

I am such a fan of Stuart Shils, enjoy the workshop!

Cheers,

Lynn

Ah This is great, I’m going to be all gushy adjectives but I love L-O-V-E Stuart! Love him, his work the way he teaches. I took one workshop with him last year and it was the best thing I ever did. The down side is if I had known about him sooner I would be a far better artist than I am. The upside is my work has grown immensely because of that workshop. He’s a great teacher. I’m blown away he doesn’t have a bunch of degrees, fooled me, and made me feel better w my little BA. If you haven’t taken a workshop with him I highly recommend it, wish I could take his May one coming up but am too poor at the moment. Thanks for posting the interview, I’ll be reading it again and again.

Ann, thanks for you comment – sorry I haven’t responded sooner but I’ve been too busy with putting the workshop with Stuart together until now. I absolutely agree with how great a teacher he is, we had a fantastic experience and after the workshop the students all told me how great this was. I may try to get him back to San Diego again next year. I will post some images and a little write up on our forum at some point soon.

Larry, the workshop was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. If I can help you bring Stuart back to San Diego at any time, just say the word. Looking at the videos, re-reading the interviews with him, all of it has so much more meaning now too. Thanks so much for making this happen.

This is one of the best interviews I have ever read about an artist trying to make sense of what he does. Stuart is just inspiring and I feel fortunate to find out about him. I could listen to him all day and read what he has to say and know I’d be learning something grand. My years of art practice have led me to this interview in a way that is meant to be. What he talks about is exactly what most artists cannot express in words. Yet he voices the processes, both of thought and practicality in such a simple way. This interview for me is a revelation and a springboard for confidence that what I was thinking and dealing with in my art practice has been a preoccupation of Stuart too.

Stuart teaches me that time is on my side and that one day I will be able to marry both my monotypes and paintings in the same way he has successfully achieved. Thanks so much Neil and Stuart.