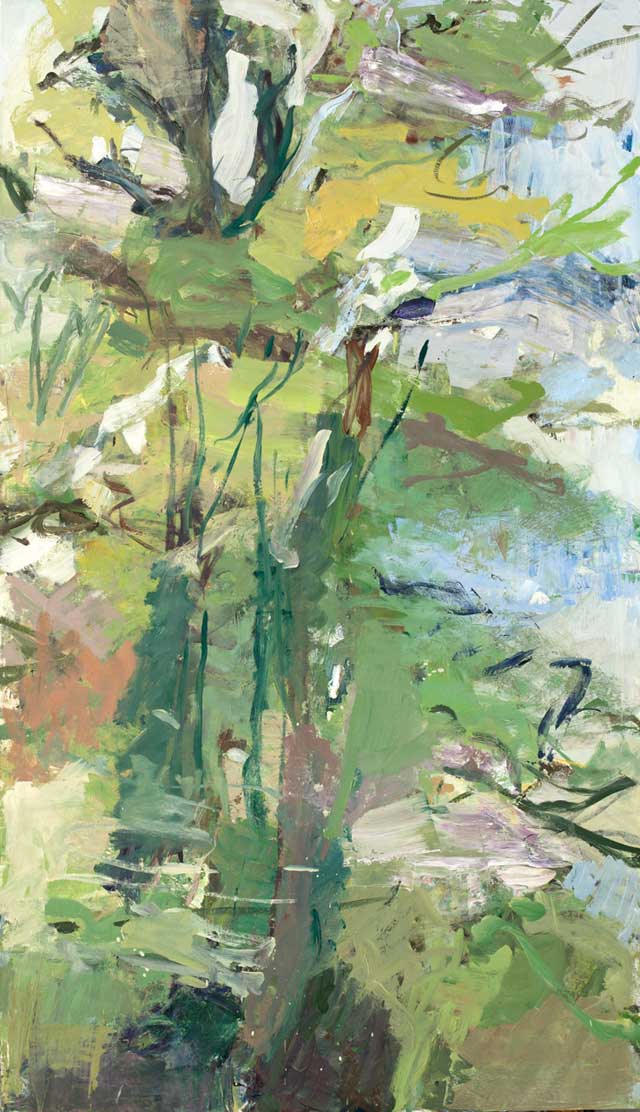

Ryan Cobourn, Garden, 36” x 48”, oil on canvas

click here for a larger view

Interview with Ryan Cobourn

by Neil Plotkin

Ryan Cobourn is a Brooklyn based artist represented by Fischbach Gallery and Ann Connelly Fine Art. Currently, Mr. Cobourn has a solo show, titled “CRAZY NATURE” at Fischbach up until May 25, 2012 and was recently included in the Dark Matters Group Show at Steven Harvey Fine Arts in New York and also The University of The Arts’ ARTUnleashed Benefit Exhibition in Philadelphia. Though Mr. Cobourn’s paintings are more abstract than the majority of artists showcased on Painting Perceptions, his working process is very firmly rooted in direct observation. He draws from life and then works from those drawings in the studio. I want to thank Mr. Cobourn for taking the time to answer my questions.

Neil Plotkin: You’re from the Philadelphia area, and you did your undergraduate work there, but I wouldn’t say that your work feels confined by the traditions of the Philadelphia painters or the traditions of Philadelphia for that matter. Was this a conscious decision, and what do you think accounts for that?

Ryan Cobourn I think going through the University of the Arts—that painting program was much more of a contemporary program. We had so many painters painting different ways, and there was more of an emphasis on doing whatever you like. I think I constructed my own painting program. I spent a lot of time with the figurative painters on the illustration floor. I was really interested in the more rigorous drawing program. I learned anatomy, and I learned painting from life. I took illustration classes and also fine art classes.

I originally started as an illustration major, and then switched to painting halfway through. It really was a self-made program that was designed haphazardly, because I didn’t know that I wanted to be a painter. All I knew is that I wanted to be an artist. So, through that undergraduate development, I developed into a painter. It wasn’t until halfway through college that I realized that I don’t want to do anything other than make paintings. That’s how it happened.

As a student, I was taking art history classes, and I was painting through art history. It sounds crazy. We were studying Renaissance art, and Baroque art, and so I drew sketchbooks and notebooks full of master copies. I did painting copies of Velázquez and Rembrandt. So I was learning painting almost in a linear way for a year-and-a-half or two years, and just developed a repertoire of—I don’t want to say techniques—but I just developed an understanding of how painting related to different time periods.

NP: You never felt like you were a “Philadelphia” artist?

RC: No. I liked Eakins. I did some copies of Eakins paintings, but I was too transitory in my nature to ever fit firmly into that tradition. There were a couple of artists that were working out of that Philadelphia realist mode that I studied with, but I think I was just too restless to settle into that tradition.

Two Trees,, 72” x 42”, oil on canvas

Clay Hill 8,, 16” x 22”, pastel on paper

The figure paintings begin in an entirely different way. They are projects that require a lot of research, and I rarely if ever start from observation. They are all from secondary sources; drawings, memory, photos, imagination. All these sources have different kinds of realities, but in spite of this, it is possible to unify the painting because in the end, they all have to serve the image that is in my mind’s eye.

So these two kinds of painting start from different places, but as time has gone by, I feel less and less of a distinction between my perception of the outside world and the more transient images of my imaginative inner world. It all seems to be made of the same mysterious stuff.

NP: You and I spoke at really great length about your process for the painting of Two Trees, and I don’t want to go over covered ground, but there is something I do want to follow up on a little bit. You mentioned that distance from your source material as being beneficial to your work. What sort of things do you think you discover or invent that you might not be able to create onsite? [Please click here to download the EBook and read the story of the creation of this painting]

RC: I feel that my own inadequacies come out… The paintings that I had done onsite when I was younger; most of them came out mushy, and everything turned gray. Maybe I’m just not decisive enough to be an onsite painter. I’ll get distracted, so in the studio I can go to town, and scrape the thing off and let it dry, and go back.

It’s more about memory and being evocative, as opposed to painting details and specificity. I’m not really interested in specificity. I’m not really interested in how many petals are on a flower or what time of day it is. I’m not really interested in that. The paintings are more about the paint reflecting a notion or an idea. So, if like Matisse said, “exactitude is not the truth”, then something else has to be the truth, which is what painting really aspires to do.

Some of the my best paintings have some kind of movement where the forms hover and quiver, and you’re not quite sure where a building or a group of trees ends and the sky begins. Think about how hard it is to paint water. The water that you just painted is not there anymore. So what am I painting? Am I painting a moment in time, or am I painting an idea about what that thing is?

Clay Hill 1, 18” x 24”, pastel on paper

Clay Hill 3, 18” x 24” pastel on paper

NP: To me, your drawings, which are done from life, are very fixed. Do you feel that they’re fixed, and that’s enough for your connection, or is that just a starting point?

RC: I started doing the pastels to bring more ideas into the studio. They’re just ideas. It’s like planting a garden. I go out and come up with twenty drawings, and there might be something in one that really strikes me. That is an idea that I want to pursue, and I’ll pursue it in the studio because it’s not about recording what was there. It’s about remembering what was there, and then changing it. And if it changes, then there has to be a significant reason as to why it changes. That’s really where the paintings have a reason to be there, as opposed to painting a photograph. It is the dialogue, it is the process of pushing stuff around.

And as much I love a painter like, say, López García—I like looking at his work, but my own personality couldn’t do that, because it’s not what I’m trying to do. I’m much more interested in exploring ideas, maybe more abstract ideas in paint, and I’m using the landscape as the relationship. It’s a relative source.

Neighborhood, 46” x 52”, oil on canvas

NP: William Eckhardt Kohler wrote about your painting, Neighborhood, saying, “It is as if, after working all of a wet winter day, the painting reached fruition with the simultaneous arrival of dusk, both, a blue-gray murk.” Would you say that is how the process of your painting goes? You’re working and working and working, and all of a sudden, everything just emerges finished? Or is it a linear process of building towards a roughly realized destination?

RC: No, it’s more like the former. I work up into a crazy, frenetic manner. I’ll work on them for an hour or two, and step back. You work through periods of intense effort and you step back and think about it for a little bit. And usually it will all come together, and if it doesn’t, then you keep working on it. It’s interesting what he wrote. He got it half-right, because that’s kind of how it happened—but I worked on that painting for two years. [Laughter] It was a moment of enlightenment, but it was a protracted and long process to get there.

Waterfalls, 72” x 84”, oil on canvas

NP: It feels like in the painting Waterfalls, the painting on the left is based roughly on drawing seven, and that the painting on the right is based loosely on drawing six. At the same time, I seems I see elements from the other drawings in the other paintings. I’m curious to know how you use the drawings. Do you look at the drawings as models, forge ahead, and then come back to the drawings to keep you on course? Or do you leave the drawings behind and at some point paint towards something unknown to yourself?

RC: I didn’t really think about it until you brought it up in that question. But the way that I use a drawing in the studio is probably about exactly the same way as if I was a figure painter, and I was painting a model in the room. It’s the same type of thing. You look at it, and you know that you are working from that inspiration, whatever it may be; but at some point you have to stop and look at the painting and realize that you’re translating that into paint.

There are moments where I’ll work on the painting, and I’ll try to make a very specific mark or movement that relates to the drawing. Then I’ll work on a painting for a while, and I feel as if it comes together, so be it. But if I feel like it’s getting away too much from the initial thing that I liked, then I go back. It’s exactly like painting a model in front of me—at some point, I have to stop looking at the model and just make the painting, because that’s what I’m doing. It doesn’t matter where it comes from. But at the same time, if it gets too far away from the model, the motif; I have to bring it back. It’s that balance, it’s that back and forth—and that’s how I use the drawings.

Exploding Trees, 40” x 60, oil on canvas

NP: There’s a lot of attention, through the arc of your career, on the seasons and weather. For example, a theme that began with your MFA thesis is work that focuses on winter. Also, you have commented in the past that the weather infiltrates your paintings.

For example, when the weather is gloomy you need to do a moody painting before you can do paintings with color in them. Do you feel that this is in your control, this attention to the weather? And is this an aspect of your work that is taking greater control over what you do? Or is it a constant?

RC: I’m not a realist painter in the sense of a realist landscape painter. I don’t go out and try to specifically find and paint what’s in front of me. What I’ll do is I’ll take the world around me (specifically, the environment) and those things relate to an internal climate, an internal landscape. I could paint a winter painting in the summer, if that’s how it felt—the same way that a musician could play a really depressing song on a sunny day. It’s more of how does the world around you relate to what’s going on inside.

Because those ideas and those relationships—I feel that is how I can relate to the viewer. I can make a variety of different paintings and use a variety of different color keys, or I can use different types of compositions. The paintings express more of an internal thing than an external thing; but it’s the external thing that is the language that people understand.

When I tried to be an abstract painter, I never found the relationship, the same sort of understanding with the viewer. I don’t think the viewer understood those as well. But if I can create an image that is evocative, and they feel like they can almost relate to it, then that is really an interesting little niche that you can get into. The transitory nature of weather and the transitory nature of our environment—that’s provocative to me.

NP: The weather impacts you in a transitory manner? Is that what you mean?

RC: It’s like if you start to think about a building, it’s as if the building is fixed. The building is set. I can’t do a painting of a cup on a table, but I could do a painting of buildings at night where things are shifting. If you’re painting the weather, or if you’re painting light, or if you’re painting air, or if you’re painting water; nothing is quite fixed.

For me, there’s a recklessness in my nature that cannot necessarily be fixed, and the paintings need to reflect that. I’m not a very patient painter. For me, the paintings are always changing, and the paintings are always very fluid, and that painting process is evocative of how my actual mind works. The forms are actually expressing that notion. They’re expressing that notion.

NP: You’re a big baseball fan. How do you use the parallels of sport to inform your work? What are you channeling with sport when you paint?

NP: RC: Well, in baseball, if you get three out of ten, you’re a millionaire. If you can make three successful paintings out of ten, you’re a genius.

People talk about the polarity between art and athletics. People think they’re completely opposite but they’re close together in a lot of ways. It really is mind over matter, and whether you’re doing sports or whether you’re doing art, your whole life has to be focused around that goal.

For instance, there’s the cliché of the dumb jock. The jock doesn’t know anything. He just knows how to shoot a basketball, or he can run fast. But that’s a real fallacy, because professional sports are really complicated. Baseball is complicated. Football plays are complicated.

On the other side, there’s the other cliché of the artist as weak and intellectually-minded but physically not very astute—and that’s also a complete fallacy, because in both art and athletics, it’s not one or the other. It’s both of those things acting together.

And in both you have to make a lot of sacrifices. You have to overcome barriers that are beyond your capabilities. Whether you want to become a great athlete or a great artist, it’s the same high, almost impossible, ambitions that you have to strive for, that you have to achieve. The mental preparation of an athlete and the mental preparation of an artist are probably much more similar than people realize.

When I work, it’s like I’m on my feet for nine hours, and it’s a physically exhausting and mentally exhausting process. I work big, so I’m making big gestures. It’s not just gesture for the sake of gesture. It’s not eighth-generation action painting. I’m still working on drawing and sorting out the image, too. It’s a complicated procedure, and I think it’s more complicated than people realize.

NP: Who is in your pantheon of artists?

RC: Well, this is a real can of worms. So, I am just going to answer with little editing. I guess the same five artists I always come back to, that most relate to my endeavors, would be:

- The Starters:

- DeKooning

- Guston

- Monet

- Van Gogh

- Turner

Obviously, they are all heavy hitters. I really don’t see the point of modeling one’s art after minor artist

- The Bench

- Soutine

- Joan Mitchell

- Constable

- Courbet

- The New York School and the Bay Area Painters/li>

- Ryder, Dove, Marin, Avery, Burchfield, and just about any of the early American Abstractionists

- Japanese and Chinese Painters of just about any century

This is a list of historic painters that I think I work in a similar vein. Obviously, and we talked about this, is a list of artists who I love who work completely opposite ways: Matisse, Mondrian, Ingres.

A list of living artists that interests me, working in a similar fashion. They are all not necessarily all famous:

- Still Going

- Leon Kossoff (I didn’t ever really respond to his work until the last show, but now, because of the new stuff, I think he is the best painter alive.)

- Bill Jensen

- Eric Aho

- Ying Li

- Barry Gealt (my teacher from Indiana)

- David Kapp

- Allison Gildersleeve

- Susanna Heller

- Susan Mayer

Probably a ton of people I forgot that should go on the still living list. Wolf Kahn, maybe. I like his work, you really have to see them in person to appreciate them. He reminds me of what NOT to do sometimes–No barn paintings.

I’m not really taking off from one specific artist. I draw from a variety of sources, but Guston and de Kooning are maybe the last guys in that line. Robert Motherwell said that everyone wanted to call the New York School Abstract Expressionists, but really Abstract Romanticism would be more of an apt term. If you think about that work in relationship to a longer tradition of romanticism, I feel like my work actually stems from not just Guston and de Kooning and Kline, but also Turner, Monet, Courbet, and Caspar David Friedrich. We can keep going back through all types of Expressionism, which is just another name for the Romantic tradition.

I try to make the paintings a lot like who I am, and the thing that people really respond to in the work is always this activity. There’s a nervous energy. I think you can see that in Guston. I think you see it in de Kooning, Van Gough, and Soutine. In those Guston abstractions, they’re not quite all the way abstract. They’re hovering there in this uneasy state. With El Greco, or Rubens, as soon as you get to one point, you’ve got to keep moving, keep moving, keep moving. I call it the “wobbly world,” a world where everything is not necessarily fixed.

I’m not just trying to paint like somebody. I’m just trying to paint like how my mind works, so I gravitate towards these artists.

NP: What is your advice for artists just starting out?

RC: Jennifer Samet was telling me that she was talking with Suzanna Coffey, and Suzanna Coffey said that her advice to young painters was to paint small and schmooze a lot. So Jennifer asked what my advice would be, and I said,

“Paint big and walk around like you own the joint.”

Ryan Cobourn is a painter’s painter. One to watch… He and his work are like ever-shifting moments in nature: raw and untamed, momentous, tangible, fleeting, Romantic, expressionistic, reflective, and real.

Go ahead. Walk around like you own the joint. You probably do.

These are really great paintings, and an interesting interview. Thanks for sharing this Larry. I really love these images. I hope I get to see some in person sometime.

LOVE his work. Thanks for this interview!

This is some of the handsomest painting I have seen in a long while.

Ryan, I find your painting the next big thing, if you are not there already. I am going to try your method, all mixed up with my method, it promises to free up all the painstaking care I have been taking, and the disappointment at the lack of creativity which they display. More power to your brush…uh, pastel or crayon or poster paints or whatever you use. Thank you for exercising your talent, it improves the world !

Ebook link doesn’t work but wow what a great interview.

Hi Linda, thanks! I checked and his website is no longer up. (also the Fischback gallery!) maybe he’ll have a new website at some point? https://www.artworkarchive.com/profile/ryan-cobourn/news/new-site-under-construction