I’ve long admired Richard Raiselis’ remarkable poetic celebrations of light and color in the urban space. I first meet Richard Raiselis when I was a graduate student at Boston University, where he teaches, in the early 90’s. I am delighted to once again get this chance to hear him talk about his painting and his background. I am grateful that he was able share his time and thoughts for this email interview.

Richard Raiselis is represented by the Gallery Naga in Boston, Ma. He is an Associate Professor at the Boston University College of Fine Arts, and his work has been shown at the National Academy of Design in New York, the Austin Museum of Art at Laguna Gloria in Austin, Texas, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others. A few of the awards and honors he has received are: the Massachusetts Cultural Council Painting Fellowship, Boston MA in 2012, The Giovanni Martino Award for Landscape Painting, The National Academy, New York NY in 2011, Wofsey Award, Stamford Art Association, Stamford CT 2010 Purchase Prize, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York NY 2001

Larry Groff: How did you decide to become a painter?

Richard Raiselis: When I was a toddler, my mother found a way to keep me busy and out of trouble. She gave me a can of water and a large bakery brush and she told me to go paint outside. We had a large cement driveway with expansion joints that carved the surface into rectangles. I would draw and paint with the water, which darkened the light cement. By the time I got to the end of the driveway, the first segments were dry, and I had new surfaces for painting. Before I was old enough for kindergarten, I remember spending more days on the driveway than doing anything else. It is funny to think that Jackson Pollock was making his paintings on the floor during those same years. Of course, I did not know about modern art.

Artist Jon Gnagy was the first performer of the first TV show broadcast by NBC from the Empire State Building on May 14. 1946 . When we got our first black and white TV in the mid-fifties, I liked to watch Gnagy’s Saturday morning “Learn To Draw” show, and to draw along with pencil and paper. At the time, I think I was four or five years old. By the time I went to school, I was much more interested in art than in anything else.

LG: What were your undergraduate studies like at Yale?

RR: I started college as a pre-med student and biology major. In the 1960’s, you might not find as many parents who would urge their children to go to art school. Art rooms in high schools then had plenty of glue sniffers. But I was lucky to have a new teacher who was enthusiastic about painting and sculpture. When I graduated from high school, he gave me a pair of canvas pliers that I still use today. His name is Louis Cormier; a couple of years ago I talked to him on the phone to say thank you for his encouragement.

The first painting I saw in college was Hopper’s “Rooms by the Sea.” It was in the college president’s living room! In one of the first fall days of our freshman year, all new students were invited to a reception at his house. The painting’s abstract geometry in service of realism was exciting, even if I couldn’t have articulated that idea then.

In the fall of my freshman year at Yale, I took biology, chemistry, calculus, and two language courses. I rowed on the crew team, and had a work study job in the cafeteria. In the spring, for a bit of relief from science, I decided to take a sculpture class with Erwin Hauer, who had been a protégé of Josef Albers. I loved the class, which emphasized 3-D abstraction. I decided to take more classes with Professor Hauer. By the time I graduated, I had taken seven. I especially liked figure modelling. Professor Hauer is a wonderful teacher, and a brilliant man. What he taught me about close observation is the core of my practice as a painter today.

In my sophomore year, I took more art classes, including Color, taught by Richard Lytle. That course made an indelible impression on me. I teach a similar class today at Boston University. Before the end of my sophomore year I had decided to major in Art. I did not phone home right away. Although I knew that my parents would be concerned that I would have a more difficult life, I was glad that they did not put any roadblocks in my path to pursuing my goal.

In my junior and senior years, I had Bernard Chaet and William Bailey for drawing and painting classes, and Erwin Hauer for sculpture. That threesome’s coaching, generosity, and warmth convinced me that I could succeed in art if I worked hard and purposefully. Today I owe much of my achievement as painter/educator to these professors, especially to William Bailey.

In my last year, my teachers supported me for a competitive travelling grant that enabled me to study Manet’s paintings in Europe. In 1973-4, I went to Spain, Italy, France, England and Holland, to see Manet’s work and the paintings that he studied for inspiration – masterworks by Velasquez, Goya, Titian, Degas, and Franz Hals, among others. During that year, I lived mostly in Paris. One of the dividends was discovering Matisse and Bonnard. I knew their work from the Met and MOMA, but seeing their pictures in the cities where they lived and worked informed my perception of their achievement. Before I returned to the United States that year, I made a brief pilgrimage to Nice to see the Matisse museum and chapel, and to visit the hotel on the beach where the painter made so many of his memorable pictures.

My Yale Art History professors taught me to think and write clearly about art and architecture. Vincent Scully, Alan Shestack, and Charles Talbot were as demanding as any educators I have known. For three years, I worked in the Yale Art Library where I shelved and repaired books as my work study job. It was there that I made the acquaintance of most of the art and art history faculty, including Seurat scholar Robert Herbert, Manet expert Anne Coffin Hanson, and Professor Emeritus Josef Albers.

LG: What can you say about your graduate studies at Tyler?

RR: I applied to the Tyler School of Art when I was in Europe. I was relieved that they accepted me. As an undergraduate with a BA in Art and a lot of liberal arts and science distribution courses, I believe that I was less prepared than BFA students from other schools who take so many studio classes to earn their art degrees. I was amazed when Tyler offered me my own course to teach drawing to Temple University undergraduates. I loved teaching, but quite honestly, I still feel a little bad for those students who had to survive my rookie year of teaching.

My graduate school teachers were some of the most well-known and accomplished painters of the past two or three generations. Stephen Greene taught Frank Stella at Princeton, John Moore is one of America’s most respected realists and educators, David Pease served as dean at both the Tyler School of Art and the Yale School of Art, and Elizabeth Cropper and Carol Zemel are distinguished art historians. Roger Anliker, my entertaining, eccentric drawing teacher, had provocative quips, quotes, and stories to amuse for a lifetime. “You can’t make a more than 40% green painting,” he said. What a great painting class opener! We spent much class time listening to him organize and defend his “top ten painters of art history” list. Chicago’s Ivan Albright is on that list. I take a serious look at his pictures each time I visit the Art Institute.

But like most grad students I know, I also had a challenging two years. It seems appropriate and normal that one complete graduate school with more questions than answers. It takes quite a few years to sort out one’s identity after school. There you are, with your diploma and your paints and brushes. Nobody cares if you paint or don’t. The freedom is at once scary and wonderful, except for the part about no job. But every artist needs a day job. It’s best just to get one, and get on with the work-work cycle.

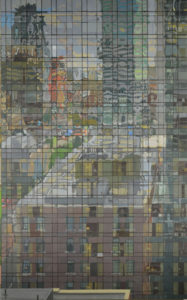

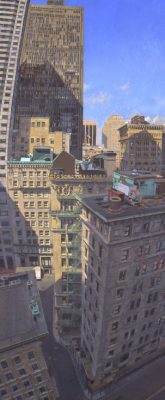

Windows and Walls, 2013/2014, oil on linen, 80×50″ , photo courtesy of Gallery Naga

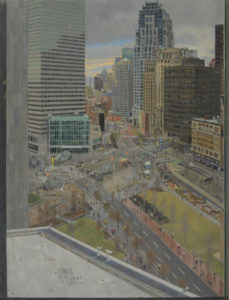

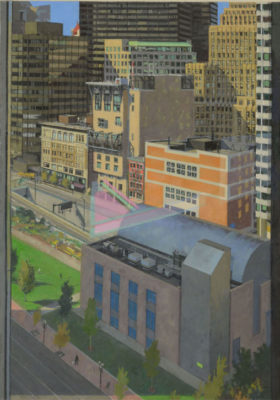

Blue ‘n’ Boogie, 2014, oil on linen, 34×24, photo courtesy of Gallery Naga

LG: Did you ever feel the need to rebel against what you learned?

RR: Mostly, I think we all rebel against ourselves, and the hard-to-face evidence that we sometimes become lazy or complacent in our work. One needs to throw a wrench in the works now and then. Of course, there is a danger of losing focus when change is too regular. But then, too much consistency can be enervating.

LG: What was it like when you first got out of school? What kind of paintings were you making then?

RR: Ha. I was all over the place. In graduate school, I had been painting pictures of my studio windows on which I had taped transparent candy wrappers and colored plastic gels to make a kind of poor man’s stained glass window. Come to think of it, my first painting in college was an indoor/outdoor painting. I have been painting windows my whole life! I continued that for a while after school, but before long I was painting cartoon-like images and making torn paper and ink brush collages that were Action Painting meets Pop Art. One summer I had a studio sublet over a pizza shop on Broadway, and I started to paint brightly colored flying pizza slices. I continued that project for quite a while after school.

LG: What painters have had the greatest influence on you over the years?

RR: How long can my list be? Let’s see if I can do this more or less chronologically. Jon Gnagy, Dr. Suess, cartoonist Mort Walker, Charles Schultz, George Herriman, Robert Crumb (is there a %#&* pattern here?), Edward Hopper, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, Toulouse Lautrec, Degas, Manet, Seurat, Matisse, Diebenkorn, Bischoff, Thiebaud, Bernard Chaet, William Bailey, Erwin Hauer, Egyptian, Greek, and African sculptors, Maillol, Gerhard Marcks, Calder, David Smith, Philip Grausman, Vermeer, Mondrian, Josef and Anni Albers, Klee, Philip Pearlstein, Neil Welliver and George Nick (who both knew how and shared how to work outside in winter), Bonnard, Marquet, Picasso (especially his analytic cubism), Piero, de Kooning, Ellsworth Kelly, Philip Guston, Constable and Monet, Canaletto, Klimt, Soutine, Thomas Jones, Morandi, i Macchiaoli, Tom Thomson, Edwin Dickinson, Gretna Campbell, Ann Ryan, Helen Frankenthaler, Harold Reddicliffe, Lucian Freud, William Coldstream, Rackstraw Downes, Andrew Forge, Euan Uglow, Antonio Lopez Garcia, Rinehardt and Martin, Amish quilts and the women of Gee’s Bend, Islamic prayer rugs, Kertesz photographs, Lou Kahn’s architecture (“The sun never knew how great it was until it hit the side of a building.”), a big cheer for Bruegel, and for cherries on the top, 17th century contemporaries Rembrandt and Velasquez, maybe the most remarkable pair last.

LG: How do you begin a painting?

RR: First I measure the motif, and decide what I want to include in the picture. Then I stretch the canvas. If my measurement is good, I won’t need to change the size or start over. Then I draw some simple geometry with charcoal. I apply paint broadly to big shapes and a few small ones for place holders. I try to figure out where saturated colors might be, and I try to key the picture’s tone accordingly. The tonal complexion of the painting is, perhaps, the most important and elusive variable. I don’t think I get it quite right most times. And working outside just makes the problem a bigger one – galleries are dimly lit compared to outside sunlight, and their track lights have a yellow, orange or pink bias. Therefore, pictures made in daylight look dark and overly warm indoors. Adjustment is difficult and maybe not such a good idea, anyway. Roger Anliker, one of my Tyler teachers, said that he lived through the inventions of gaslight, incandescent, fluorescent, halogen, sodium vapor, and then, I guess, LED lighting. Which should he trust? He chose daylight.

LG: Do you draw everything out on the canvas first?

RR: Just big rectangles and polygons.

LG: I would imagine with painting complex reflections that even moving your position a little, changing the angle of your head, is likely to make a big difference. Is that something you have to worry about?

RR: I take my cue from Cezanne on the mountain; I just move a little and there’s a new picture!

LG: Is measurement an important part of your work, how do you go about that? Do you use a plumb line or other device?

RR: I have a tiny hand-held transit that helps me to find the horizon when it is obscured. I use a weighted string plumb bob, and some rulers with numbers. Sometimes I use a proportional caliper that I made.

LG: How do you decide on what to paint?

RR: Opportunity, and that little voice you hear.

LG: What led your to painting from high vantage points and why?

RR: In middle school, I tried to make a drawing as if I were on a roller coaster, about to crest and speed down the tallest hill. That’s my earliest memory of it. In college, I wrote a paper about the Renaissance perspective invention of painting what one art historian called the “foreground plateau”, as we see in Bruegel, for example. That is when representing what’s high up is represented down low on the picture plane. In the Trecento, for example, artists drew the hill as an upward diagonal and placed their figures on that hill, at the top of the picture. Putting objects in the highest position at the bottom of the picture was a remarkable step toward verisimilitude, and anticipates photography.

LG: Do you have problems being next to a window and getting the right light on your canvas or similar technical issues?

RR: If I stay in one place long enough, the light returns. It sometimes can be a long wait.

LG: Will you ever work on a painting both in the studio and on site?

RR: Yes, but not if I can continue it on location.

LG: Historically most great paintings have been studio creations and not from direct observation; what does observational painting offer that studio-based works often lack?

RR: Surprise, surprise, surprise.

LG: Any interesting stories related to painting on site you could share?

RR: Kids on the street are the best critics. They are outspoken too. They will point to a place on my painting and say, “you should work on this part for a while.”

LG: Do you still teach your course in methods and materials for painters? I’m curious about what role your extensive knowledge of painting techniques plays in your own work. Do you use any special mediums or paints?

RR: Yes, I’m still teaching that one. Thank you, Reed Kay, for entrusting your baby to me 28 years ago. It’s good to know a little about the structure of a picture so that you can have some freedom with technique. That sounds backwards, I know. Nobody has to make a painting to last 100 years. But if you know how to make one, you can proceed with more options and with better instincts. Painters have so many screwy ideas about craft — about fat, lean, thin, thick, gloss, matte, lightfastness, about gesso and canvas, etc. Much of this confusion can be worked out in a few hours of informative talk about pigments, binders, and layering paints. It does not help that some manufacturers are not forthcoming about the products that they sell in art stores. But Gamblin and Golden, Strathmore, and Winsor and Newton, work hard to correct artists’ misconceptions, and they are strong leaders in technical education.

Technically, there are no formulas for making masterpieces. Like a soccer game played by professionals, painting is about invention. Rules give us the framework, and we improvise the game. A soccer game without rules and a predictable sequence would be one that nobody would watch.

As for my take on method? I think simple is best. What could be better than a single layer of unmodified paint on a sound white support. I can’t do that very often, but when painting in layers, I want to be sure that the layers are relatively thin, not diluted excessively by thinners, and that they have a little time to dry between applications. I have been using alkyd mediums because they speed drying, they add a little resin/oil ingredient to the mix, and unify the surface. I haven’t had a painting crack since college, so that’s good news. I like Frank Stella’s idea to try “to make the paint as good as it was in the can.” That’s easier said than done.

LG: Do you work in an all over fashion gradually going from broad to specific, building up layers of paint or do you paint more directly completing one area at a time?

RR: I work all over. I call it democratic painting. I wish I could get it right in one or two layers like George Nick and Hal Reddicliffe can. I’m more impatient I think, kind of “shoot now and ask questions later.” My paint is kind of milky in viscosity, but the surface sometimes ends up crusty with layers. But every picture is different.

LG: How important is getting an exact color equivalent to the color of you see? What are some considerations with color in your work?

RR: Good question, and an impossible one to answer well. I often say that I paint what I see. I do my best to paint the differences that I perceive where colors touch, both inside a form, like the change of color on the sunny and shady sides of a house; and outside the form, like where a roof meets the sky. Every pair of colors that meet make a “join”, like the place where two bricks touch. My job is to analyze each pair for lightness/darkness, color, and intensity of color (dull red, or red right out of the tube?) But it’s not that simple, you know. Light that reflects off a granite building has light of every wavelength reflected from every surface. It’s a virtual color stew. If I see red-ish, blue-ish, green-ish, and yellow-ish light in the same shadow, how do I choose a color? Analyzing the biggest color “joins” for relative contrast establishes the foundation. Then, moving from larger to smaller, and from general to specific, I worm my way into the picture. If there are 1000 more color pairings, or 10,000, each “join” must be measured and balanced for relative hue and luminosity, both individually, and relative to the larger field. That’s where the “tonal complexion” of the picture shows its face. Sometimes that face is not too pretty. I tell myself that the first color I apply in a painting can be anything. And that the last color I apply can be only one thing.

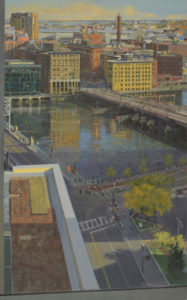

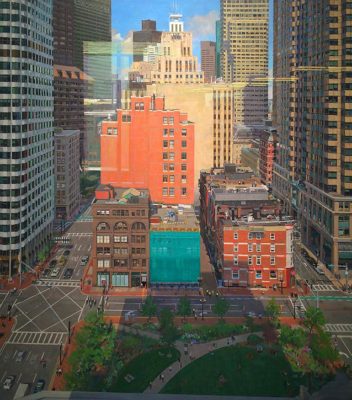

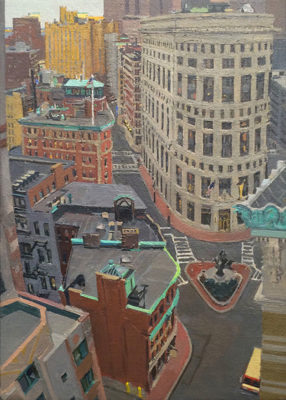

Dewey Square in Silver, Green and Gold, 2014, oil on linen, 42×32″, photo courtesy of Gallery Naga

LG: Light must play a critical role in your work. What are some considerations with using color to respond to the experience of light in nature?

RR: This business is alchemy, you know. We do our best to make mud into light. It’s not only representational painters who seek to make this transformation. It’s the common problem of all painters who devote their efforts to this elusive magic trick. You feel it in Paul Klee, Ad Rinehardt, and Bridget Riley, too. Some painters like to draw on ipads or make video. Those mediums already use electric lamps as their binder, so to speak. The ipad surface is a grid of lights. Some of us still prefer the challenge of the path of greater resistance. Here’s a good recipe – take colored dirt, beat in an equal measure of vegetable oil until you have a homogenous, uniformly darker, slurry that stands in peaks. Then using fingers, knife, or other utensils, liberally spread this grease on a gorgeous piece of linen. Now make the surface glow. How can that get old?

LG: Are there any special geometric compositional concerns with your work like using a golden ratio or do your compositions evolve in a more intuitive fashion? Is work done on site less likely to follow notions of a geometric ideal?

RR: I explained earlier that I measure my motif before I stretch my canvas. Sometimes, when vernacular meets ideal, they make a happy event. I try to let the situation do the talking, and I do the walking. I’m very interested in the notion that some Renaissance painters used proportions for their pictures based on the proportions of a divided lute string as it played the octave (1:1), the fourth (3:4), and the fifth (2:3). There are names for these proportions, diapason, diatessaron, diapente. It’s really a beautiful sort of poetry.

LG: I’ve read that you are a big jazz aficionado and that elements of jazz play a role in your work, can you explain this more what this entails? Is a sense of rhythm important to this?

RR: I have been playing music since I was in the first grade. My father pulled a tenor saxophone out of a closet when I was six. I did not know that he owned an instrument. He played “I Only Have Eyes For You.” That song is etched in my brain. I asked him to teach me to play. I carried that instrument to school and to garage band rehearsals from second grade through high school and college. My college graduation present from my parents was a saxophone of my own. After grad school in New York, I was lucky to take lessons from the late Paul Jeffrey, a Monk sideman, Mingus arranger, and educator. I play in a group now with well-trained musicians, two of whom write new improvisational music. We play now and then around town, sometimes at art events — at the MFA, the De Cordova Museum, and at BU. We played a Second Saturday event at Gallery NAGA a couple of years ago. So naturally, I think about parallels between musical harmony, rhythm, and improvisation and color harmony, rhythm, and improvisation. Those parallels are fascinating, if imperfect. Ted Nash, a saxophonist in the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra and a double Grammy winner this year, has composed music about painters (Matisse, Monet, Picasso, Dali, Pollock.) And he has improvised solo saxophone music on alto while performing in front of selected paintings at MOMA in New York. I follow his newsletter and enjoy his contributions to this blurring of disciplines. I’d like also to mention the wonderful poetry of Poet Laureates Billy Collins and Robert Pinsky, who articulate their love of music with humor and spot-on interpretations of mid-20th Century jazz. Pinsky, a saxophone player himself, reads his poems in performances with piano virtuoso Vijay Iyer, among others.

LG: Do you listen to music when you paint?

RR: No, not anymore. In recent years, I have enjoyed quiet while painting. I’ll crank up the volume when building stretchers or stretching canvas, though. Both WMBR and WHRB still have good jazz radio shows during the day. It was a sad day for me when WBUR stopped playing jazz (yes, they once did), and WGBH funneled jazz to a couple of weekend slots. Thank you, Eric Jackson, for your history and expertise.

LG: What determines a painting is finished for you?

RR: When everything I do seems to make the painting worse, I consider stopping. The end of a painting is like the last day of a vacation: I’m feeling a little sad, it’s hard to be present, and I’m distracted by my daydreams for the next picture. When architect Louis Kahn was asked which of his buildings was his favorite, I heard that he said, “My next one.”

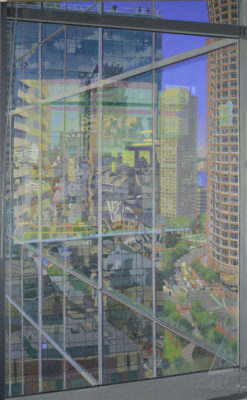

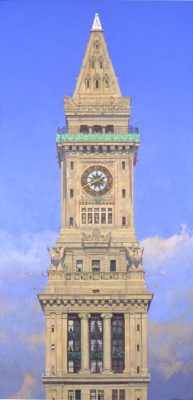

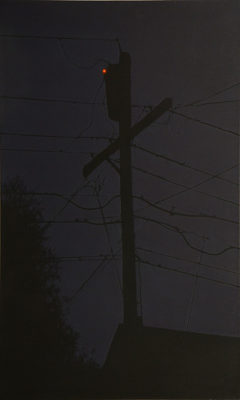

Silver Seven, 2014, oil on linen, 48×30″, photo courtesy of Gallery Naga

Great to see your thoughts on painting Richard,and see the paintings that are wonderful ..and thanks LG for the effort ..

Great Interview with Richard!

Always admired his paintings.

I had the pleasure of being his drawing and painting student at Tyler School Of Art in Pennsylvania and in Rome Italy.

Nice to hear the mention of Roger Anliker!

Cheers!

Russ Fama

Russ Fama,

At a yard sale, Purchased a framed piece of art with your signature. Seller’s name RAGNI.

Said her father -who played sax – got this piece from you….maybe 40 years ago.

In PHILLY/Roxborough.

Mark Gibbons

mark.d.gibbons@questdiagnostics.com