I am grateful to the Michigan painter, Richard Kooyman for agreeing to participate in this email interview with me where he talks about his background and evolution from being an observational landscape painter to paintings from imagination and inspiration from art historical sources. He also talks about his interest in philosophy and politics how that can relate to painting.

Kooyman received a BFA from Grand Valley University and a MFA from Ohio State University in 1982. In 2013 Nominated for a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters Grant and has also been awarded; a Michigan Council for the Arts grant, the Michigan Governors Award, and a National Endowment for the Arts grant. Kooyman exhibits his work in numerous venues in Michigan and nationally.

Larry Groff: How did you become a painter?

Richard Kooyman: I became a painter through the back door of craft. I initially wanted to work with clay so I went to Ohio State University to get a MFA in ceramics. I’m drawn to making things and working with my hands and now feel that there is an intimate sensibility between art and craft. I didn’t begin to actually make paintings until years after I graduated when I just happened to take a landscape painting class from Melanie Parke. It was pure chance. I had seen one of Melanie’s paintings that made me pause and think that maybe I wanted to paint the landscape like that or at least begin to paint. Melanie taught me to see through the eyes of a painter.

LG: Please tell us something interesting about your background and/or art school experience that remains important to you today?

RK: When I was 11 years old old I was hit by a car on my bicycle. I severely fractured my leg and had other injuries and was in the hospital for several months. My injuries kept me from playing sports which was what most midwest boys were told to do back then. I think this accident played a big part in me becoming an artist. It spared me the team sports indoctrination so many youth were put through and led me down a different path in life. The accident helped steer my attention to better and more important things in life, like art.

LG: How did you wind up in Northern Michigan? Do you still also work and live in Chicago for part of the year?

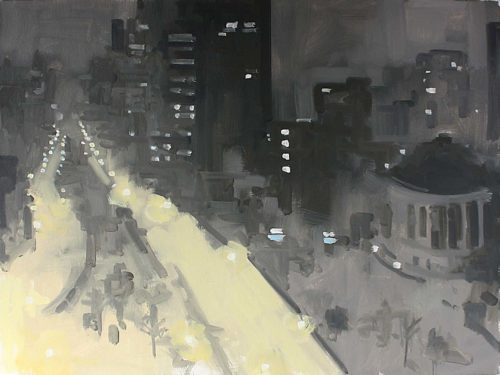

RK: After graduate school I was offered a job building small wooden boats in Frankfort, a small coastal town on Lake Michigan. I didn’t have any money for my own clay studio and building boats was another type of making that seemed like it could be interesting. That job lasted a couple years and I really liked the vibe of living in NW lower Michigan so I stayed. But Northern Michigan can also be isolating from the rest of the art world. After I met Melanie and we got married we set up our studios and home in a 110 year old store front in an even smaller rural northern Michigan town. In 2010 we started to worry that maybe the cultural isolation was turning us into the UniBomber so we decide to split our time between Michigan and Chicago. We each got studios and lived there for almost 3 years. It was a really important time. We treated it like going back to school and availed ourselves to every art opening, lecture, and art event the city had to offer. Chicago is a diverse art city and the numerous universities offer lots of different public programming, and of course there is the great Art Institute of Chicago.

We no longer have a place in Chicago but make it a point to take extended trips to NYC and Rome. I think it’s really important to work at staying as relevant and educated an artist as I can be. If you live in a rural area you can easily become reclusive.

LG: What is the Northern Michigan arts community like?

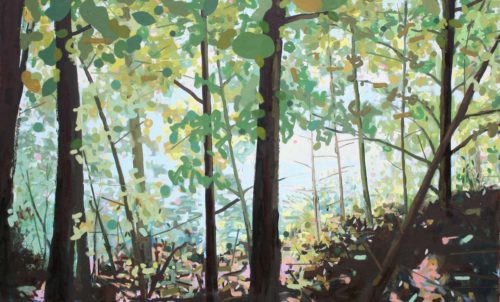

RK: We are spread out. You may have to drive 30 minutes or an hour to have a studio visit with another artist. Artists up here are trying to build there careers like any urban artist does, there just aren’t as many local opportunities that larger urban centers have so you have to deal with that aspect. We just have to travel more to connect and socialize. But we also have incredible natural beauty.

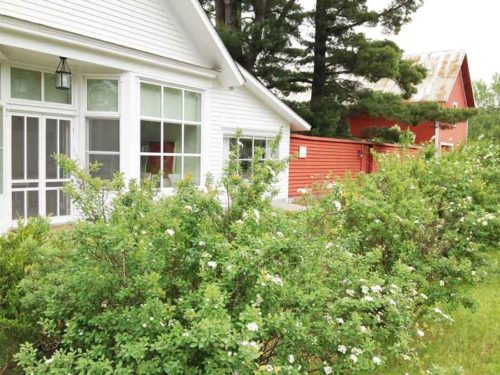

LG: You have an amazing studio and living space as well as a community artist space. How did this come about? (read more on this hyperallergic article Making an Artistic Life in Northern Michigan by Philip A Hartigan)

RK: Melanie bought this 115 year old store and barn complex before I knew her. She was looking for a studio/living piece of property and stumbled upon this historical property. Several years later we got together and really began working on the place. The barn became my studio and shop and the old storefront became Melanie’s studio. There is a small living quarters which was built on the side of storefront which is about the size of a trailer. So we have big studio spaces and a small living space which is perfect. I think I have repaired or replaced just about everything over the years. The spaces are really wonderful. We have about 5 acres of land and this summer I’m building a screened in outdoor painting studio. It’s a real artist’s compound in a lot of ways.

LG: You are married to the painter Melanie Parke – how much does her work influence you and vice versa?

RK: A lot. Melanie is a very focused and driven artist. She puts a lot of time and research into her paintings which I hope is rubbing off onto me more and more. We think alike about many things but especially about art. Because we live in such close proximity to our studio spaces we learned early on when to ask for feed back on what we are working on. To know when is the right time to say something. But again this is part of living in a very rural area, you rely on each other to talk and ask questions about the art making process and it’s a great pleasure to share a cup of tea and talk about what we are seeing in each others work. Melanie also has a really quick and open eye so when she sees my new work she actually can assess it better than I can. I’m learning to trust my instincts more.

LG: What influences have been most significant to your work?

RK: The answer to that question seems to keep changing as I get older. Lately I’ve been writing about my work and being an artist and I keep remembering early influences from varied sources.

Like when I was a boy my family visited a relative in the Netherlands who was a landscape painter. I remember his shop and how you pulled back a heavy velvet curtain that separated the shop from the apartment. That curtain felt like something magical to me.

The Bill Moyer’s interviews with Joesph Campbell was foundational for me as an artist. I listened to tapes of those interviews so often I began to memorize Campbell’s answers. Campbell taught me that being an artist was an important and needed societal role, that artist are the true cultural leaders.

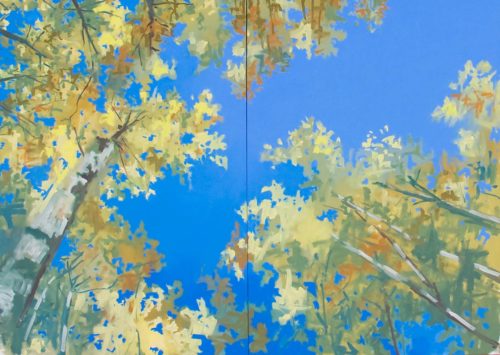

I’ve been influenced by painters such as Victor Higgins, Georgia O’Keefe, Tom Thomson, and Fairfield Porter whose painting practice were part art, part environmental immersion. They all seemed to share the painterly sensibility of O’Keefe who said, “There is nothing less real than realism.”

Then there are people like Guston, Joan Mitchell, and Terry Winters who taught me that there were ideas behind paintings. And of course important ideas about beauty from the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans, so my influences are pretty wide. Not to mention so many great current artists doing just mind expanding things. I recently saw a great show in NYC by Emilie Stark-Menneg who uses florescent pop imagery and beautifully crazy drawing in her figurative paintings, and the Biala show at Tibor deNagy just blew me away. Biala is another woman painter who history has overlooked and undervalued. Her paintings of room interiors and Venice are fantastic.

LG: I understand that you currently are no longer painting landscapes, and instead paint more figurative compositions that seemed to be sourced from other art, especially ancient Italian art. What brought about this decision?

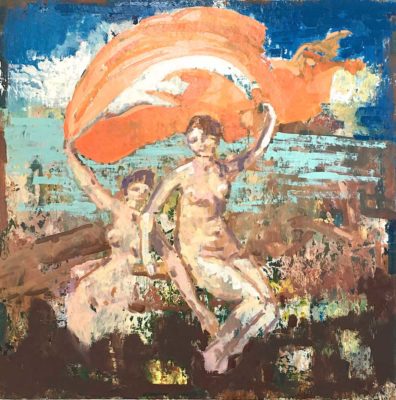

RK: A trip to Italy. I’m a little embarrassed to say I had never been to Italy until three years ago. Melanie and I were invited to do a residency in a private villa in Tuscany owned by the then American Ambassador to Italy. The trip blew my mind wide open. Italy is filled with a history of paintings about love, sex, food, religion, wars, individual people, and politics. Paintings that tell stories, that represent ideas, that symbolize beliefs, and I was left with the overwhelming feeling that I want some of that energy in my work. I want to put more of that into my paintings. I want to make paintings that do some of those things, to tell a narrative, to symbolize something in addition to the landscape.

LG: What does your current work offer that your landscapes didn’t give you?

RK: On our first trip I started to make paintings about the Italian landscape. Those paintings slowly became about ancient made up landscapes, and I still make some of those kind of landscapes. These are about the feeling of a landscape but also about old fresco surfaces and worn canvas. I like questioning what existed both in the landscape and on the canvas that now has worn away? How is something like an ancient fresco which probably doesn’t looks little like it did when it was made still considered beautiful to us? I like questions like that.

You can’t visit Italy and not be moved by the amount of ancient world history that is visible just by standing on a street corner and looking around you. I started to think about what of all that history I could pull from and bring forward. I became interested in how our idea of beauty today was similar and different than in those ancient days. What have we lost and what have we gained in our quest for the new. And just painting the Michigan landscape wasn’t enough anymore. I wanted more.

LG: Has your painting process changed since you started this new subject matter?

RK: I’m the type of person who needs to remind myself that in art I can do anything I want. It was easy for me in the past to simply think that I couldn’t do something because “I’m not that kind of artist”. Like why can’t I be working on two completely different ideas, two different bodies of work at the same time? Why not? Last year I worked on a body of colorful figurative paintings and a body of minimal abstract line drawings.

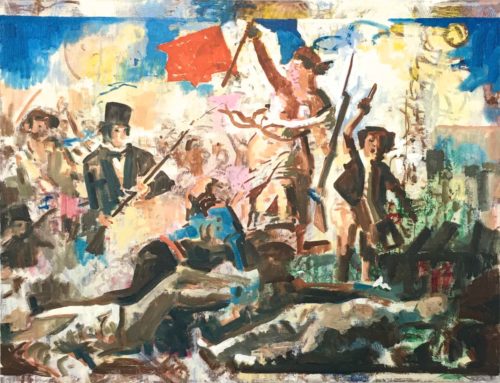

The art in Italy gave me that permission to change and my process has also drastically changed in the last couple years. In my current work I’m projecting parts of historical paintings onto the canvas. I have this little projector that I use to project images that I adjust to define the figures which I then begin to add to a painting. I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to paint projected images but the room is dark and every time you try to paint a section you are blocking your view and the image shifts when the canvas is depressed. It’s both controlled by the projector and totally out of control. It’s kind of like Brice Marden taping his brush to a long stick to challenge his control of the brush. There is a degree of flying blind to the process and when you turn the lights back on the whole thing looks different. I then move back and forth between projecting and working directly. It similar to how we squint at a painting when we are working on it to generalize what we are seeing.

LG: I understand that you’ve been interested in Heidegger’s ideas about the power of art. Have you read his The Origin of the Work of Art? I tried, and failed to read his philosophy in the past, finding much of this philosophy difficult reading and required more time and patience than I had available.

I’ve heard that art theory and philosophy are a big part of many art schools today, especially graduate programs. This isn’t something I experienced in art school back in the 80’s and have felt that art school should emphasize studio practice and concentrate on teaching the fundamentals of art over theory. However, I’ve recently starting to wonder how well I’ve thought this through and wonder what philosophical ideas you might have found that would be valuable for painters to learn along with their craft? Is there a beginner’s level text to art and philosophy you’d recommend?

RK:With Heidegger I think it helps to have a guide. For one thing he was a German philosopher so there are issues of translating really long and complex German words, and on top of that Heidegger made up a lot of his own words for his philosophical concepts.

For anyone who is interested in reading The Origin of the Work of Art I’d recommend you run out and get Iain Thomson’s Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity. Thomson is excellent at unpacking everything Heidegger in a clear and digestible manner. He helped me understand concepts and definitions I would have never got had I just read the essay.

Heidegger questions our modern notion that we, as the subject, approach the art object and draw from it what it has to offer and take that ‘experience’ back to our own life, our own bubble so to speak. Heidegger contends that’s not really what happens or what should happen when we experience a work of art. He believed that the aesthetic experience actually takes place in the space between me and the art object. This space is filled with a openness, a potential of sorts, and that the function of art is to hold that “openness” open. Another way to put it is that the value of engaging with a work of art is that it opens us up, it keeps us opened up to potential, to new ways of thinking, to change. That openness isn’t something that just the viewer can do on their own and it isn’t something that sits in the art object but it’s engaged in the act of viewing, in the space between you and the work. And that no other human action really does that in the way that art can do it. That’s just a beautiful thing I think.

Another one of my favorite books is Philosophies of Art and Beauty: Selected Readings in Aesthetics from Plato to Heidegger edited by Albert Hofstadter and Richard Kuhns. Each chapter is a quick summary of an individual philosopher’s ideas on art. It’s a book you can take your time with and which can give you an over all view of how our ideas of art have changed so much over time.

LG: Can painting be verbal as well as being visual? Should it?

RK: Our reaction to a painting can include being verbal. How can that be a bad thing? Some suggest that writing or thinking theoretically about art can take something away from the aesthetic experience. I don’t think that’s true. In a lot of cases it adds to the experience. It’s really about how you approach art.

This is part of what Heidegger was saying, that you shouldn’t approach the work of art with only your own closed agenda, whether that agenda is verbal or not. That would be setting yourself up to miss the aesthetic experience. But you also can’t just approach the work of art completely objectively because we are human with all the biases and preconceived ideas that being human involves. We aren’t just an empty vessel. So for Heidegger the experience is acquired in the middle.

LG: I have read about your protests against ArtPrize, the international art competition based in Michigan, funded largely by the Dick and Betsy DeVos Family Foundation. ArtPrize as a $200,000 prize awarded by public voting as well as other significant cash prizes that attracts many painters and other artists. Please tell us something about why painters should boycott ArtPrize and what is happening with it and your protest activities in 2018?

RK: The short answer is that ArtPrize was started and funded by Betsy Devos and her husband Dick Devos and if you want to do one little thing to take a stand of resistance against this political horror we are living in then you shouldn’t participate in something that benefits Betsy DeVos.

Their son Rick DeVos came up with the idea for ArtPrize but Dick and Betsy, the DeVos family, and Amway are the major money behind it. Betsy was the director of the board of ArtPrize up until she went to go work for Trump.

If you never have heard of this pair of ultra-right wing, evangelical political activists, they are the money and driving force behind so many bad things happening to our society. They are the Koch Brothers of the midwest and they get a lot of cultural cache from playing with this big art competition. They call it their “social experiment.” So why would artists want to play their game?

Last year Melanie and I organized a Facebook group called DeVos/ArtPrize Resistance. We formed it right after Trump was elected and DeVos went to work for him. At the time I felt it was the least of what I could do. It was one way to take a stand on a local level.

The DeVos’s aren’t really interested in art. What they are interested in is using artist’s free labor to create an economic development plan for the City of Grand Rapids. It’s a tourist event to draw people to Grand Rapids to spend money. In 2016 ArtPrize made $28 million dollars for the city off the backs of artists who had to pay for everything including an application fee.

The reaction to the boycott has been mixed. Lots of artists get it and support us and yet many still look the other way and insist that politics and art are separate. What’s really been disappointing is to see big name artists and curators, people like Jerry Saltz, who get wined and dined to go and participate in the event as jurors. We contacted all of last years jurors to educate them about the DeVos’s and asked them to disinvest themselves. None of them choose not to participate or even wrote us back. That’s really discouraging and sad.

(for more about this ArtPrize boycott, follow this link to the griid.org interview with Richard Kooyman )

LG: How can the making “beautiful things” still be relevant in the age of Trump?

RK: Oh, wow, that’s a questions I know so many of us as artists are struggling with. I struggle with it. But I think it’s far, far deeper than Trump. We are now fully immersed in a neoliberal world that undermines our political agency and undercuts our chances of being able to live the artistic life. I firmly believe it wants to undercut us. The current neoliberal system doesn’t care about the artistic life. It doesn’t value it.

LG: Can you explain a little about how you define neoliberalism? I think some people, especially painters who may not be very political, might be confused by what you mean by that term.

RK: The definition has changed over the years but today neoliberalism is thought of as a socio/political ideology that believes that everything people do and think should revolve around economic markets. Michel Foucault said that neoliberalism turns everyone into a “enterprise of the self”.

Neoliberalism wants us to think that everything that is important in life has to do with business and entrepreneurialism. This thinking has changed how arts organizations and institutions talk about art by changing the language used in the art sector.

If you listen closely you hardly ever hear art being promoted through the NEA and state arts organizations in terms of it’s intrinsic or philosophical value, but rather in terms of how much monetary value it adds to the economy. That’s neoliberalism. The “Art Works” slogan of the NEA is neoliberal. What does “art works” even mean? It’s working to do what? You won’t hear them talking about how art works by allowing a sense of transcendence into your life, or how artistic expression can be a political force of change. Instead they will talk about how art is important because it “works” as part of the economy, how many jobs it adds, or how much money it brings in. That’s neoliberalism and it reduces the importance of what we do as artists to economic numbers. It strips the aesthetic experience of any philosophical or mystical aspect and by suggesting that good art, art that works, is art that can be measured and marketed.

That’s not why art is important to our lives. Art adds a richness to our lives that has nothing to do with market forces or economics. I believe art is the antithesis of neoliberalism.

This winter I read Maurizio Lazzarato’s book The Making of the Indebted Man. Artists need time to develop and space to grow and one of the biggest obstacles to that growth has been our debt economy, an economy that Lazzarato says “has been conceived and programmed as the strategic heart of neoliberal politics”.

We all have to deal with debt to pay for college, for transportation, for rent, but artists have it really hard because we can’t necessarily get credit because we don’t have a steady income. Lots of artists today have to work at other jobs which takes away time from their development. Its a vicious debt driven circle and it’s killing the artist. Did you know the word “artist” isn’t even used in the NEA’s mission statement anymore? It’s sad because while I think the community between artists is really strong and vital right now, it also seems like artists are slowly disappearing in terms of the general public’s interest. This is neoliberalism at work.

I could be wrong. Museum shows are packed which is a good thing but does the person on the street believe in art enough to live with a great painting, or do they just want to Instagram it? I do know that painters would benefit greatly if people spent as much on art as they do on iPhones.

Like any time of crisis this is a real potent time for artists. This is not time to shrink from our ideals. This is the time to double down on our efforts, our visions, and our dedication to what it is we do. This is also not the time to be silent as citizens.

LG: A hundred years from now, the effects of Climate Change could become so severe as to pose an existential threat to humanity. If you lived then and were chosen to be on a large committee, each tasked to choose one painting to save in an indestructible time capsule for any surviving civilization in the distant future. Considering you’d never see it yourself and the future civilization finding it might not know anything about art or our culture – what would you choose and why?

RK: Ok, I’d pick the room of 4 frescoed walls called the Villa of Livia at the Museo Nazionale Rome. It’s believed to be a room used by Livia Drusilla who was Emperor Augustus’s wife. Standing in the room is like standing in a Roman garden. Each wall is filled with plant and tree and bird species of the time. It’s literally a record of flora and fauna of the time. It would show this future civilization that at one time we valued nature.

Then again maybe I’d want them to know we loved to play with color and energy and I’d pick a Joan Mitchel canvas. But part of me thinks they should know that we were terrible assholes and I’d pick a large Kara Walker wall piece to go along the Mitchel or the Villa of Livia.

Good interview. Richard’s ideas are clear and compelling.

Thank you both!! I think that this is one of the best interviews you’ve done Larry! Very interesting and inspiring Mr. Kooyman. Thank you.

Excellent, compelling read, Richard. I agree about AP. As always, your paintings are beautiful! Thanks.

Always interesting to hear what talented people have to say about their work.

About their political views, not so much.

Being an artist is a political choice.

Thank you for introducing politics into this discussion of art. There’s no reason why artists should pretend not to have political opinions, and simultaneously no reason to think that art cannot be its own excuse for being. I too bemoan the measuring and marketing of art at the expense of its mystical and philosophical value.