Peri Schwartz, Bottles & Jars #8, 2012 Watercolor on paper 15 x 22 inches

When Peri Schwartz was asked in an earlier interview by Harryet Candee “What is your dearest motto, philosophy, or message for yourself?” Peri Schwartz answered: “This quote from Willa Catha keeps me going:

“Every artist knows that there is no such thing as “freedom” in art. The first thing an artist does when he begins a new work is to lay down the barriers and limitations; he decides upon a certain composition, a certain key, a certain relation of creatures or objects to each other. He is never free, and the more splendid his imagination, the more intense his feeling, the farther he goes from general truth and general emotion.

Nobody can paint the sun. or sunlight. He can only paint the tricks that shadows play with it, or what it does to forms. He cannot even paint those relations of light and shade – he can only paint some emotion they give him, some man-made arrangement of them that happens to give him personal delight – a conception of clouds over distant mesas (or over the towers of St. Sulpice) that makes one nerve in him thrill and tremble. At bottom all he can give you is the thrill of his own poor little nerve – the projection in paint of a fleeting pleasure in a certain combination of form and color as temporary and almost as physical as a taste on the tongue.”

– Willa Cather, Light on Adobe Walls

Peri Schwartz is currently having a show of new watercolors and drawings at the garvey|simon art access gallery in NYC ( May 15 – June 15, 2013) This show’s press release states that Peri Schwartz:

“is not exactly a still life painter. She builds abstractions out of real forms. The objects do not inform the work as much as the artist informs the objects. Schwartz does not merely paint or draw what she sees; she first creates what she wants to see until it is there, and then she puts brush to canvas, charcoal to paper. She uses glass bottles filled with colored oils for their translucency and layers these vessels in front of each other until the desired hue or opacity emerges, and then she paints it. If she knows she wants a particular shot of color in her work, she will bring it in. She will physically paint an object the color she wants and work it into her composition if needed.

The work is rigorously formal yet never stiff; the surfaces have a loose brushwork and casual air that make them very inviting. The steely charcoal and ink drawings on Mylar are bold and almost architectural. Drawn with a confident stroke, towers of books lean on and support each other; traces of grid marks define the picture plane, and then disappear – forcing the eye to jump to the next landing spot. The drawings are punctuated with dark and light shifts that keep the gaze zipping back and forth.”

Peri Schwartz has exhibited her work extensively for the last 30 years, and can be found in the permanent collections of institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Corcoran Gallery of Art, DC; Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The British Museum, London; The Arkansas Arts Center, Little Rock; Biblioteque Nationale de France, Paris; New York Public Library; and the Yale University Art Gallery. She received her B.F.A. from Boston University in 1973 and her MFA from Queens College in 1975. She is represented by a number of galleries including garvey|simon art access, NYC, Gallery Naga, Boston, Page Bond Gallery, Richmond, and Gerald Peters, Santa Fe.

Interview by Cody Upton in Peri’s Studio in New Rochelle, NY February 26, 2013

(ed. note: Cody Upton is a writer who lives in New York City)

Cody: When did you first start using the grid?

Peri: In art school, the practice of looking at a painting and dividing it into a grid was introduced as a compositional device. Later, when I was doing self?portraits, I had to get my body in the same position every day. I was working from life, in front of a mirror, and I started to mark lines on the wall behind me so that I would know where to position my head and arm. Soon I included the lines in the painting. They became part of the composition.

Cody: What made you decide to put the grid lines in the composition?

Peri: I was holding up a ruler and looking at those straight lines and I guess it just seemed natural to put them in.

Cody: Did you put them in initially as guides?

Peri: Probably. I still see the grid as a guide, in a way.

Cody: But then it also became something more?

Peri: Yes. Everything is more interesting with the grid. The objects take on more weight, more appeal because they are in this space of verticals and horizontals. If I was going to work on a composition and the grid was not in it, it wouldn’t hold any interest for me. I like seeing the intervals of blank space. That’s a musical concept. You have the quiet of a white shape and then you have sound.

Cody: How faithful are you to the things you paint?

Peri: I am religious. That bottle is the prosaic reality that I’m trying to reproduce. The fun is in finding the right organization.

Cody: So if you want to paint a bigger bottle, you get a bigger bottle, or you move the bottle closer?

Peri: Exactly.

Cody: And if you want to change the color of that board, you paint over it with a different color?

Peri: Right.

Cody: When you paint the board red, do you use the same red paint on the canvas itself?

Peri: No, that’s a cheap paint that I get at the paint store. They’re Benjamin Moore colors. I look at the color charts to see which ones I want.

Cody: And what about the books? Have you ever painted the cover of one a different color?

Peri: No. That I haven’t done. But I’ve rejected a lot of books because of their color. I go to Strand and pick out books for their covers, not necessarily because I want to read them. They’re props. I just got this new book, this beautiful blue book. Isn’t it gorgeous?

Cody: It’s turquoise.

Peri: I was so excited to find this. I had all these beautiful oranges and reds but my palette had become too warm in the foreground. This blue connects well with the color of the tabletop.

Cody: So it’s almost like putting a puzzle together.

Peri: It is.

Cody: How long did it take to set up this particular composition?

Peri: It took several weeks but it isn’t like I set it up and then begin drawing. I keep making adjustments. It is never really done.

Cody: You know, I only just realized that you produce the grid physically on the objects you paint.

Peri: Right. I think that’s probably unusual. I don’t think it’s common to draw the grid on the books, the tables, the walls, on everything.

Cody: Do you think your compositions change because the grid is actually on the things that you’re drawing or painting, as opposed to just on the paper or the canvas?

Peri: No. The grid is a fluid thing. I’ve learned, that when you paint over something that is good, the new version is often even better, because you let the old layer come through. A lot of my painting is about what’s underneath. It’s not just a one-shot thing. I’m not interested in the Frank Stella shape. I like the Diebenkorn shape, with its feeling of layers, of color upon color. It’s not just a block outline. It’s a shape that’s shifting.

Cody: From the point that you lay down the first piece of tape or the first line of charcoal to create your grid, to when you actually start drawing, how much time passes?

Peri: It’s more of a back and forth. I start drawing, and then I put down some of the grid lines on the wall. It’s a lot of sitting down at the easel and saying, “Wait a minute, I need this or I need that.”

Cody: Is painting always the end result? Do your drawings always lead to painting?

Peri: No, they don’t. I love to draw. In this instance, I started a drawing and thought I wanted to do a painting of it. I ordered the canvas but in the interim, I got to the point where I said, ‘Oh boy, I really do love to draw. Maybe I want this to be a print.’ I started talking to Maurice Sanchez, who is a lithographer, and he introduced me to Mylar. He uses Mylar instead of a stone to make lithographs. Once I started working on Mylar, which has such a creamy translucence, I completely forgot about doing the painting. I was happy to just draw. I drew for months, but eventually I got to the point where I wanted to paint again. I wanted to deal with color.

Cody: Do you ever draw in color?

Peri: Well, I just did a series of watercolors, and I have worked in pastel, but I love black and white.

Bottles &Jars #9, watercolor on paper, 2012, 15 x 22 inches

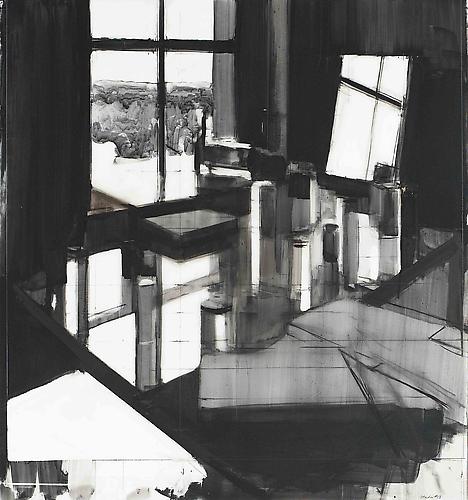

Studio #15, 2013, ink and charcoal on mylar 40 x 36 inches

Studio #13, 2012, Ink and charcoal on mylar, 30 1/2 x 28 inches

Cody: Wasn’t it Maurice Sanchez who introduced you to watercolor? He said that you needed to work out the colors that you wanted in your lithograph in watercolors, which led to you doing a whole series.

Peri: It was great switching to watercolors. The red is different in watercolor than it is in oil painting or in monotypes. It has a great, delicious redness to it. You also have to think about the white of the paper. In general, I’m conscious of that anyway, but you become very sensitive to any little bit of white that’s poking through, and you have to ask, ‘Do I want that white or not?’ So you’re using a different part of your brain. That’s really important, particularly since I stick with the same subject for many years. To introduce a new medium is useful, inspiring, and motivating. It gets you going again. You see everything in a different way.

Bottles & Jars XII 2011 20×30 Oil

Cody: You forwarded me an Igor Stravinsky quote that was important to you. It says: ‘Composing for me is putting into an order a certain number of interval relationships. The faculty of creating is never given to us all by itself. It always goes hand in hand with the gift of observation. The least accident holds his interest and guides his operations. One does not contrive an accident, one observes it to draw inspiration there from.’

Peri: That perfectly encapsulates how I feel. The intervals are the grid, which is all that empty space. You need empty space. And then sometimes accidents happen, and you say, ‘Wait a minute, that half an inch to the left seems a little more interesting. I’m going to use that.’ That accident is what it’s about. The one thing I don’t want a painting to look like when it’s finished is finished. I want it to be an open question. Things shouldn’t look like they’re exactly where they’re supposed to be. The composition shouldn’t feel stagnant.

Bottles & Jars XXI 2011 22×36 Oil

Bottles & Jars XVI 2011 22×36 Oil

Cody: So how do you know when a work is finished?

Peri: When I begin to say, ‘I’ve had enough of this.’ Sometimes I come into my studio and say, ‘This works!’ It’s like a surprise.

I never think of the grid as a restriction. I see it as an enhancement. It contains my work in some way, but ultimately gives me freedom. And then there is the fact that I want to work from life. That’s another restriction. It’s so important to me to have those pieces in front me.

Cody: Why is that?

Peri: In art school, I loved working from a model. Anytime they said invent something, I never found that exciting. In one drawing class, we had to light ourselves up from below. It was such a great problem. I had never drawn myself with light coming from below. I saw this whole new world, but it was from life. It was a concept that we were imposing on life, and then we went from there.

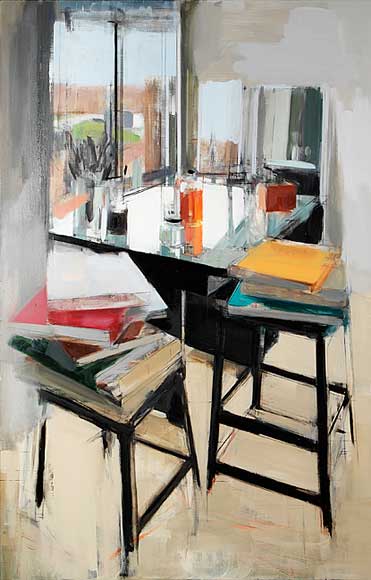

Studio XVIII 2007 56×44

Studio VIII 2005 62×40

Studio XXIII 2010 60×38

Cody: When you paint what is actually in front of you, do you make decisions about how to abstract it?

Peri: I do. But it’s more like note taking. That’s a red shape, that’s a yellow shape, rather than that’s a particular object.

Cody: You said perspective isn’t really something you think about because the grid makes everything into a flat surface. It seems that in itself is a form of abstraction.

Peri: Yes. I want to make these exquisite, organized things that sit on the edge of abstraction. My paintings are realistic—you do get a sense of space—but they are also abstract.

Cody: What subject do you think you’ll work on next?

Peri: I don’t think there is a next. This is next. We’re in it.

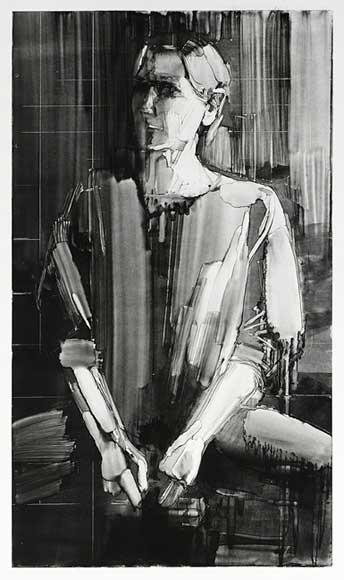

Self-portrait 2009 monotype 36×21

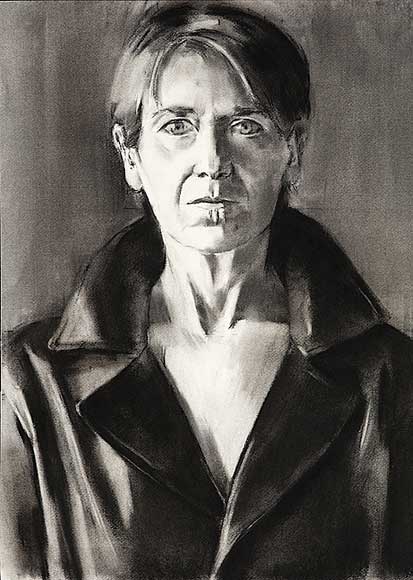

Self-portrait 2003 charcoal 23×16

Very impressive and beautiful work.

Fascinating process. I’m reminded of Euan Uglow’s fastidious setups, and of course Antonio López García, both of whom were/are known to mark the actual objects of their perception to help fix them empirically. But you actually take the process a significant step further, insisting in a way that life imitate art. The still life isn’t still because you discover ways to improve it in the process of (abstractly) depicting it. Like Joshua Reynolds, you seem to see your role as improving nature by its own rules. Or maybe you are more like Max Ernst’s father: the surrealist ridiculed his realist father for going out and chopping down a tree in the garden because it interfered with his painting composition. Frank Auerbach loves to tell that story, but identifying with Ernst père not fils!

Beautiful planar resolution. Louisa Matthiasdottir and Jean Helion come to mind.

Mondrian meets Uglow, meets Shils! Fabulous!