Please note: several images in this interview link to a “zoomify” viewer where clicking the image allows you to zoom and pan, much the same way one uses google maps. You also have the ability to enlarge the viewing area to fill the browser window with button on the right-most part of the toolbar below the image)

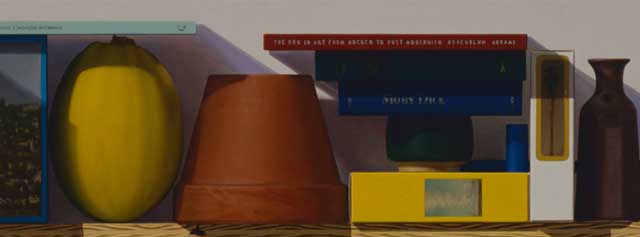

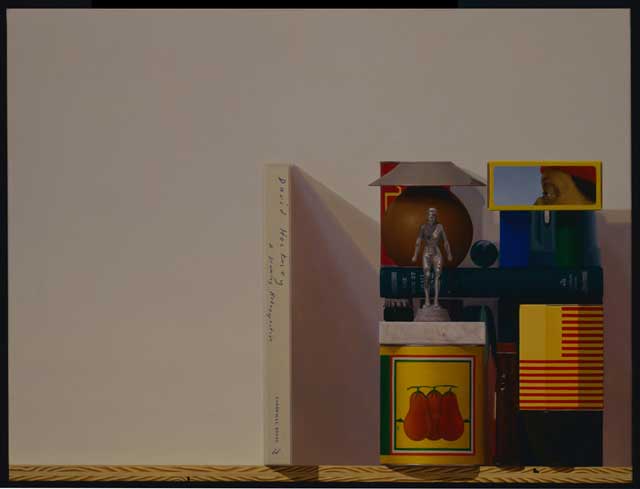

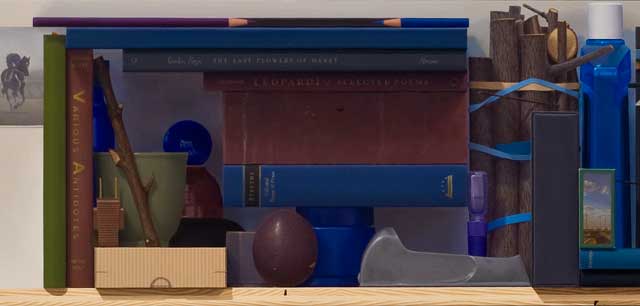

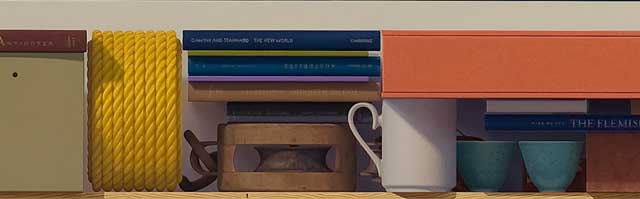

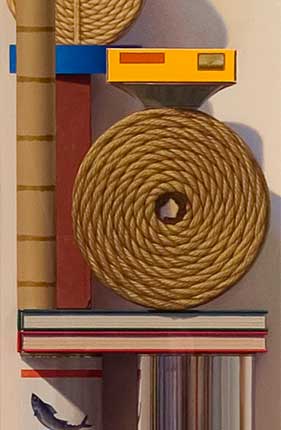

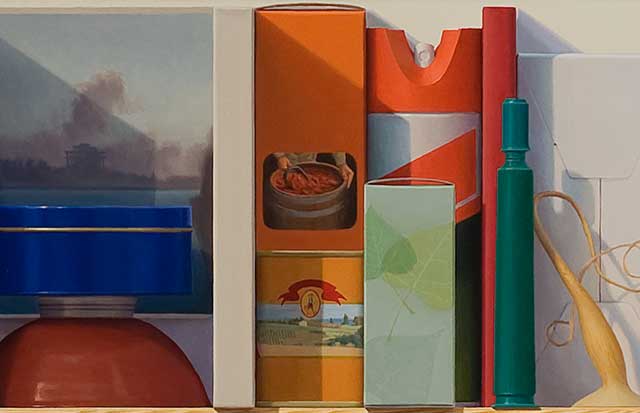

About a year ago I saw several of Michael Tompkins’ paintings during a visit to the Paul Thiebaud Gallery in San Francisco. His long horizontal still lifes in particular captivated my attention with his tour de force of relentless geometric arrangements of artbooks, bottles, and fruit as well as empty paper towel tubes, Melita coffee filter box, bug spray, ropes, and tree branches that go beyond formalist structure to renew our faith in the power of painting to astonish us.

What is remarkable about these paintings isn’t just the amazing technical skills in achieving these monumental structures but in how he makes it seem like it’s all such great fun. There is musicality in how intervals of placement, color notes and scale juxtapositions along the relentless horizontal and vertical thrusts that seem to mash up Bach fugues and Phillip Glass with Spike Jones and Captain Beefheart. Perhaps most of all I was enchanted by his color. The delights of color here isn’t just for it’s descriptive pitch accuracy, or even for the many satisfying moments where you feel the rightness of the sensations of one color plane vibrating against another. What got me most was the magic of feeling I was listening in on conversations between color groupings—how the reds and blues seemed to be speaking (or perhaps singing) in slightly different dialects of the same paint language, some mute or just whispering, other maniacally chatty, muttering or even yelling bloody murder—all which keeps your eye moving back and forth trying to figure out what it all means.

Many of his extremely long horizontal still lifes are titled “barges”. One definition of a barge “is a long flat-bottomed boat for carrying freight, typically on canals and rivers, either under its own power or towed by another.” I was struck with an idea that perhaps these barges could be powered by the viewer as well as the painter, like the interactivity involved in the reading of a poem. Fueled by the movements of eye and brain, slowly towing the these barge-poems down dendritic canals to berth in the ports for unforgettable images.

In the 2004 Paul Thiebaud Gallery catalog essay James Housefield wrote:

“In Tompkins’ art, things nestle into place as if they were bodies moving through space. Like rush hour travelers, the objects compress, cluster, separate, and congregate anew. As objects from one painting reappear in another, they shed the qualities of things and acquire the qualities of actors upon a stage. In Tompkins’ world, these objects take charge of the lives that are their own.

These are paintings about the craft of painting. They are, equally, about the labor and the pleasures of the artist’s studio. Yet they are also always about the pleasures that the visible world offers to us all. Tompkins’ art offers precisely crafted vistas into the poetry of things.”

From the 2004 Paul Thiebaud Gallery catalog – Michael Tompkins Painting: 1986-2004 by James Housefield

I was thrilled that Michael agreed to this interview and would like to thank him greatly for taking the time out of his busy schedule and for the thoughtfulness of his answers.

Michael Tompkins lives in Berkeley, CA and is represented by the Paul Thiebaud Gallery, San Francisco, CA. He studied at the University of California, Davis, CA (1983 MFA in Painting, 1981 BA in Painting) He received the National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Fellowship in Painting and the American Academy and Institute of Arts & Letters, Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation Award in 1989 Additionally he received the National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Fellowship in Painting in 1987.

Larry Groff: You studied with Wayne Thiebaud when you were in school at UC Davis in the early 80’s. Can you tell us what it was like to study with him? I’ve heard he often works more from invention and memory. Was observational painting encouraged then?

Michael Tompkins: I arrived in Davis in late ’78. There was a very unlikely, very lively atmosphere there, generated by a faculty who were all hired when they were young by one guy with pretty good judgement. It was a new department in the early sixties at what had been the agricultural annex of UC Berkeley. Wayne was joined by Robert Arneson, Roy de Forest, Manuel Neri, William Wiley and a number of others with lesser names but equal talent. Funk was the lingua franca, and fit the farm field location like a glove. The overriding rule seemed to be “work a lot but don’t take yourself too seriously”. We did a lot of paintings on brown butcher paper and made a lot of trips to the landfill, but it did produce artists like Bruce Nauman, Deborah Butterfield and Nancy Rubin.

I’m saying all of this to provide context to your question about Wayne Thiebaud. I think if you want to understand him as an artist and teacher, that context is key. He’s a very sophisticated, highly intelligent, educated and articulate guy. But if he springs from Chardin, Corot and Morandi (he does, all three), then he’s equally grounded in George Herriman, ‘Ramblin Jack Elliott and the Great Basin.

Yes, we worked from observation in his classes, but I should say that he taught almost exclusively beginning classes. I’d arrived there from a junior college where I’d had all of those but he let me repeat them, multiple times, for no credit. I think he felt, and still does, that lots of good things happen in among basic issues; describe a plane or the meeting of two planes (think of Bruce Nauman’s videos of his studio corner), ride up and down the calibrated scales of color and value or find the physical sensuality of light and shadow. All of this was put into a very workmanlike regime, where he introduced each project and expected everyone to do it the same way, separated only by degrees of success. We were learning a craft, learning conventions, with plenty of room among the rules for accident and discovery. But. I remember some very serious lecture demonstrations like one about Picasso, where he drew on the board the hyphens, commas and hash marks of analytical cubism and its shifting planes, all very entrancing, with the final half circles completing the ears of a cartoon Koala bear climbing a tree.

LG: You used to make panoramic landscapes, often from invention and sometimes incorporate still life into your landscapes. What was it like for you in your early years as a painter?

MT: As a student, until my last year of graduate school I painted abstractly. I studied and imitated Richard Diebenkorn’s work, particularly the Ocean Park paintings. I worked summers as a carpenter and made big painting/drawings using chalk snap lines on canvas, stained with watery washes. Red, yellow, blue and the white of the canvas. Eventually I lost the thread and took up traditional figure painting, using myself and Grace (my wife) as subjects, always naked, just simple exersizes in rendering a subject. After a few years I started looking for more anonymous subjects, so tried plein air landscape painting. A series of teaching jobs with long commutes didn’t leave much time for outings, but I had come up with a rudimentary understanding of light and atmosphere. My chance for observation was on those commutes, and I was often moved by segments of the drive. working from memory in studies, then on panels,I tried to recreate the experience of a landscape as seen through a car window, a passage through time of segments woven together with a continuous vantage point. The idea worked with the flatness of the Central Valley. When we moved to the industrial fringes of the Bay Area I changed subjects again, this time to the refineries near our house. I thought they were beautiful, as if Morandi’s cans and tall necked bottles could give off Turner’s steams and Whistler’s vapors on sunburnt hillsides. The formats were conventional rectangles. Something from the Valley landscapes persisted though. I really liked the idea that a painting could imply a narrative by its own shape, and be composed in time frome one end to the other and back again, with passages like music of density and openness. I tried to apply still life to it, with objects on a plywood shelf arranged in sparse intervals. That was about twenty years ago.

I think your question implied something about viability and survival as well, and of course that’s more complicated. The bare facts are that I taught for about seven years after graduating, and at the end of that period I got a series of grants, all based on the landscape paintings, that enabled me to paint continuously enough to generate a living from the studio. Grace has been a professor of painting and drawing at CSU for almost thirty years, and we’ve been working side by side in our studios since we were undergraduates.

LG: Is there any one thing that has been most important to you? Something more than anything else that has made you the painter you are today?

MT: No, not one big thing. I think it’s more a cumulative series of people, ideas and experience that shape us. Some more important than others, no doubt, but I wouldn’t single out one in particular.

LG: I’ve read that your love and study of both Italian and Northern early renaissance painters such as Piero Della Francesca and Hans Memling has been formative influence on your work. Can you tell us something about how these painters influence your still lifes?

MT: I had a really terrific teacher in Junior College who, when talking about the idea of influences, suggested that being influenced was a very healthy thing, but we shouldn’t stop there. We should, in his words “go to the source”. So as a student when I was enthralled with Diebenkorn, a deeper study would point to Matisse, Bonnard, and then their sources. When I was painting the figure I was really drawn to Gregory Gillespie and Phillip Guston, both of whom drew heavily on sources in the early renaissance, Guston from Piero, and Gillespie from Carlo Crivelli. I’ve never connected with Crivelli but found, like most of us, a mountain in Piero. In ’92 Grace and I bartered for a house in Gubbio for an extended stay. By pure luck it happened to be the 500th anniversary of Piero’s death, so as many works as could be assembled from around the world were brought right nearby; to Arrezzo, Sansepulchro, Monterchi, and especially Urbino, where, among his paintings were his mathematical treatises, pages opened with illustrational drawings and calculations. For me it illustrated a very human notion that we could devise or discern some kind of order in a wildy, kaleidoscopic world. His sense of order had such dignity! But I also found a very singular sense of time in Piero, that long, extended, almost infinite moment, like one that John Cage describes between the end of one note and the beginning of another in music. I found a lot of magic in paintings whose characteristics might otherwise be described as stiff or wooden, but were really operating with a powerful inner pulse.

I’ve found parallel sensations looking at the early Flemish painters, especially Van der Weyden, Memling and Petrus Christus.

I’ve used, or tried to use, a lot of aspects of this very old language for my own aims. I make small worlds out of very recognizable objects, carefully rendered so that their physicality can be believed. But I treat them also in a way that they would never be encountered in the physical world, partly in the attempt to slow them down. Everything is rendered as if every part of every object is always at eye level, so like the earlier landscapes there is a continuous vantage point. Everything is in roughly equal focus, without heirarchy, inviting a further look at a lot of junctures that might otherwise play more supporting roles. In a Memling for instance, I’m equally drawn to the tiny landscapes in his portraits as I am to the sitter. It’s a visual experience that asks me to hang around a while. I also use a kind of artificial ordering or collecting of objects, partly echoing the architectural settings that Piero found useful for his stories, like the Flaggelation picture in Urbino or especially the meeting of Sheba and Solomon in Arrezzo.

LG: Morandi still lifes are painted stylistically very different than yours but many of the issues he’s involved with are echoed in your work. In particular, I’m fascinated by the spatial tensions and ambiguity in your work. Is Morandi someone you think much about?

MT: Wayne Thiebaud was, and is a great admirer of Morandi’s work and spoke about it with a lot of passion and reverance to us as students. It was contageous. I remember an episode of the old TV show “Barney Miller” where Dietrich is going on, passionately, about the Chekovian interplay between Curley and Moe in the Three Stooges. One of the other detectives walks in and says how he likes the episodes with Shemp. Deitrich then looks away and says “I see we have nothing further to discuss”. I guess that’s how I feel about any artist who says they don’t get Morandi. Thankfully that doesn’t happen often. My two cents on the subject is, among other attributes, I find his work to be a combination of extraordinary skill and extraordinary humility. And yes, those marvelous spacial ambiguities are one of many things I’ve tried to cop from him.

LG: How long does it take you to set up your still life? Do you establish a careful drawing first or do you paint very loosely and then gradually refine?

MT: The still lifes from the 90’s had relatively few objects in them so took only a day or so to set up. More recent things may have 80 or 90 objects so maybe a week. I do start with a careful drawing, trying to get things into scale with each other mostly, and that takes another week for an eight foot painting. I paint on wood with 6-8 coats of gesso because once I start painting, things inevitably don’t work, so I’ll sand sections out and restart. The initial drawing is still useful though as I try to calibrate the size of things, one to the other.

LG: Is the set up in the studio the same as is ultimately seen in the finished painting or does it change dramatically over the course of painting?

MT: I can’t recall a painting ever remaining the same composition from start to finish. There are always subtractions and additions, sometimes major overhauls, sometimes after a few months I sand the whole thing out and try something new.

LG: Are you faithful to the setup or is it more just a point of departure – how important is observation throughout the painting process?

MT: I’m faithful to the setup in degrees. Sometimes I paint things in that aren’t in the setup at all, like landscapes or portraits or copied portions of paintings I’ve been looking at. I generally eliminate the printed labeling on cans, boxes and bottles, and I have to invent, or at least extrapolate the appearance of things because I just don’t see everything straight on that way. I nudge something about what I see into an artificial system.

LG: Please tell us something about your process in painting. Do you generally build up the painting in a layered, indirect manner or do you work more directly? Any special palette or method of working other painters might find of interest?

MT: I work in a way that’s pointed towards opacity at the end with a very even surface, so I start with a very simplified first layer that looks like a watercolor, brushy and teansparent. That gets sanded to a ghost image then a second pass is made, with a little more indication of light and local color. That gets sanded again, changes made and gradual refinement on to a fourth or fifth layer. Sounds laborious but with thrills along the way. In slow motion.

My pallette is pretty broad. Because I use so little paint, I indulge in lots of variations of color, with a section for umber/sienna/ochre, and separate areas of reds, yellows, blues and greens. I’m not partial to any brands, though I really like some more recent efforts by American companies. I use cheap brushes.

Studio, outside

Studio, inside

LG: You must have a huge studio. I’ve read that you often have multiple setups going on in the same time. How do you manage having such long horizontal still lifes? Why do they hold such interest for you?

MT: On the contrary, I have a small studio that my brothers built for us.I have a shelf on one wall with a worktable I made specifically for the long paintings. The panels lie flat on the table and I made a little arm rest thing that glides above the surface, keeping my hand steady and helping me draw and paint straight lines. It’s a very low tech mechanical aid, made of some 2×4’s and some leftover baseboard trim, but it works. A miracle I think.

As for maintaining interest, I guess if I wasn’t interested I’d be in more trouble than I already am. But I’ve decided I need to do these very specific paintings, and I haven’t found any shortcuts, and my desire to see each one through is enough. I also find that many of the strongest pleasures (and greatest disappointments) are at the end. I think it’s my ridiculous good fortune to get up every morning, make it through the rosebushes to my studio and do some version of what painters do, even if mine take more time than some. I deal with the flow of ideas in sketchbooks, studies, drawings, watercolors and oil paintings on paper. Things that are faster and have their own unique pleasures. I’m always interested.

LG: In many of your paintings there is an interesting compression of the space, like you were viewing everything from a great distance using binoculars. This accentuates the horizontal and verticals in the picture. Often we see your objects frontally with no perspective orthogonals. Why in our post-modern era is maintaining “the integrity of the picture plane” still so important?

MT: I want there to be tension and play between the illusion of objects in space and devices that conspire against that. For instance, taking a cylinder, like a soup can, and painting it as seen straight on, as a rectangle, flattens it, but using another device, like light or reflection that reasserts its cylindrical nature, is at least a little unsettling. It’s a plea to spend some time there if only to figure it out. I do it on a broader scale by gathering many objects into a single, usually rectangular shape, like the cubes that crushed cars become. It’s one thing and everything. It’s an extremely artificial, ridiculous imposition of order on what is a kaleidoscope of shape and pattern. It’s the same with the internal geometry you noted, verticals and horizontals, posts and beams. It’s a caprice that tries to hold what’s inside of it at bay.

My feeling about the now post-postmodern era is that it’s a great time to be an artist. It’s the great age of pluralism where everything is in play, and where notions of picture planes and other systems can be mixed and matched and all muddied up at the service of peculiar visual experiences. I don’t know that I’d deem anything irrelevant.

LG: You seem attracted to the color of everyday American life – stuff you see on the shelves at CVS or ACE hardware. The poetics of your painting is played out with the color conversations and geometry. The precision is your forms emphasize the flat colors against each other. The call and response of colors and their shapes to each other keeps our eyes moving through the picture. What words could you share with us about the color in your work?

MT: Yes, the paintings are depicting pretty mundane things. A pair of pliers. A can of corn. I’ve often titled them Barges, thinking of the craft that lugs our cargo around. Cleopatra had her version. These are mine. I don’t go around looking for objects to paint, I practically trip over them. I may as well put them to work, as stand ins for comedy, tragedy, sensuality. If I look hard enough I’ll always find something there. I’m in a long line of artists working those mines. I know I’m not interested in a critique of consumerism or political tomes. I’m embracing these things, and if they’re successful the only irony would be that they could transcend their own identities and become systems of color as you described, or honored guests at their own ball, or perform a pavanne on a plywood shelf.

The way that color functions is staged and premeditated. I look for and sometimes find after the fact, harmonies and echoes of shape and color that are either played up or down. Paintings tell us what thet want that way. I thought your comment about the color of American life was interesting. I don’t know that I’ve ever thought of it in precisely that way but I can say that after being in Italy for a while I came home with the clarity that I wasn’t Italian, and that there was something deep in the soul of Morandi’s paintings that was very very Italian, from particular color harmonies to the tempo of his brush. If such a thing as American color happens here it’s probably because I haven’t thought of it and haven’t tried to control it.

LG: Your still life objects don’t evoke nostalgic associations but they’re not just mundane objects with only formal purposes either. You invite the viewers to create their own poetry and narratives out of stuff more likely to found in a recycle bin than the ye olde curio shop. What are some of the things most important to you in regard to subject matter and narrative? Why paint the stuff you do?

MT: You may have answered the first part of your question better than I could, along with some comments I’ve already made. I would only add that if these things ever do work, they’ll say the same thing we all want to say, that I was alive here and now and it felt something like this, or this, or this. I select objects democratically and ask that they stand up straight and play a part. One thing and everything. It’s an arrogant aspiration but worth a try.

Detergent, Glue, Towel-Roll 3 1/2 x 4 1/2 inches watercolor on paper 2013

Windex 5 1/2 x 10 inches watercolor on paper 2013

Excellent work and excellent interview. I have used the same Morandi book in my set- ups.

Especially loved the watercolors.

What wonderful, witty, painting. I particularly like the compression of space that occurs viewing all these objects in a frieze, and the emphasis on an American ‘consumer product’ vernacular. The ‘gaps’ that occur when the type face is left out (say, from an Anchor Steam beer label, or Off bug spray) perpetuate a logical rhythm within the paintings and engage me as the viewer by allowing me to fill in, or somehow, complete these images. Great work and engaging interview.

Wonderful interview. Thank you.

Nicely done – interview, and of course the moving art that inspired it. Thank you both.

Very nice interview and incredible work. Thank you.

Great work Michael, love them.