Thaddeus Radell wrote in his review of the 2013 Kyle Staver Tibor de Nagy Gallery show:

…“Staver is a brilliant inventor whose success lies in her commitment to her inner vision that is at once original and sophisticated and she is remarkably adept at rendering that vision into cohesive luminous constructs. From a broad, almost confused spectrum of diverse shapes and shielded color, she synthesizes clarity. And so she transforms the modest room allotted her into a theater of sorts, where the viewer can expand their own imagination by feeding into her ever-ebullient, seriously odd vision.”

I was fortunate to meet Kyle Staver recently and interview her at her home and studio in Brooklyn, NY. I’ve long been enchanted by her paintings and was excited to finally be able to see her work in person. I would like to again thank Kyle for taking the time to speak with me at length about her work and concerns as an artist.

I told her how much I marveled over her incredible compositions but it wasn’t just the formal beauty I responded to; it’s also the humanistic dimensions–I feel empathy with her characters and storytelling, that this was a refreshing reprieve from the grimmer examples of postmodernist nihilism and irony. She responded that it was critical that her paintings:

“communicate what it’s like to be a human being for Kyle Staver” and that “The humane part of painting for me, It’s just that I’m not a jerk.” She then went on to say that “It’s so much easier to say I hate you than it is to say I love you, there is nothing risked in saying fuck you, nothing; but everything is risked if you say I love you and mean it.” When I paint, I’m always trying to not pitch, if I have two figures close together and it’s romantic I want to hold it and give it teeth. I’m not against irony, I’m against a kind of ironic delivery system that only delivers the fuck you. If I made romantic paintings without the pull in the other direction, and I think that’s why a a painting needs irony, to keep the painting taut. I don’t want to be a sentimental painter or have the paintings be flabby. I think that the irony is the pull in the opposite direction.”

Kyle also discussed how important the community or tribe of artists has been for her growth as a painter. Kyle gives back to this tribe not just with her influential paintings, teaching and personal support to her many artist friends; but also with her Facebook postings, which for many painters around the world, has become an important new way to start their day, reflecting on the vast power and interconnectedness of art.

LG: What has been some of the most significant influences for you as an artist?

KS: Whether you’re writing, making music or going to a bar to talk to people, it’s all about connecting. I happen to find myself a visual thinker and maker. At a certain point in my life, a woman at a boarding school named Mrs. Moses told me she knew what was wrong with me and what was wrong with me was that I was an artist. She said that it was ok, that there was a whole tribe of artists and not only was there a whole tribe but there was a whole culture. Meaning I wasn’t the only person that did this.

If Mrs. Moses hadn’t told me that I was an artist I probably would’ve stayed in northern Minnesota making knit sweaters and macramé. I would have made things. Minnesota artists make marvelous things, I’m not dismissing that. It’s just that I had the good fortune of finding out that I needed to make things.

I had the great good fortune to have someone direct me to this great culture of visual making and communicating where I met my tribe. Natalie Charkow, who helped me apply to Yale – as she was going through my slides said “you know the one thing you need is you need more culture”, and that was exactly right. I knew nothing except I had to make.

LG: By culture she meant?

KS: That I didn’t know enough beyond a certain group of painters that I liked. I thought the sun rose and fell on Soutine. I still like him, but I don’t love him like I did, but that’s like thinking that when I moved to Brooklyn that Brooklyn was tiny but once I lived in Brooklyn it’s enormous. And so that’s all Natalie was saying to me, it’s wonderful to fall in love, to feel connection and feel like your nervous system is being understood by another artist.

LG: So you studied with Natalie Charkow Hollander? I’m curious how she may have influence your bas relief studies for your paintings.

KS: I studied with her at Yale. I took Natalie’s sculpture class and it was the best drawing class I ever had in my life. I started off as a non-figurative sculptor, came to painting late. I took Natalie’s class when I went to graduate school and she would have us do these little figure models. At the end of the day she would make us smash them telling us “no one would be making Christmas presents in her class“! You’d work on this piece and then she’d just make you trash it.

At one point we had to make a relief of a painting and of all the paintings in the world to choose from I chose a landscape by Van Gogh, a hay wagon in the middle of a yellow field. It has a massive space, a crazy thing to try and make a relief out of, I don’t know what I was thinking. This relief was extremely thick. Natalie said the best thing that could happen to you was to just drop your relief face down, flat on the ground. But after Natalie’s class I always built my paintings into very thick reliefs, I don’t know what Natalie would say about that but it helps me with some things in my paintings.

LG: When you say you build the painting you mean your clay moquettes, you make these bas relief as studies for paintings?

KS: No, I make them concurrently. I do a lot of different things when I’m working on a painting. Sometimes when I’m painting I get into a corner and I have a painting that’s like a mule that just sits down and no matter what I launch at it, it won’t move. So, if I back out of the stall, back out of the studio, make a print or work on a relief—I can usually find another way in—that the mule isn’t expecting. So everything that I do is alleys to plow back into the painting. I do build paintings, I do watercolors of them, I do a million drawings of them and it is all concurrent—it’s like the debris that the painting generates. But Natalie was the first person that I made a relief with.

LG: I’m curious to hear about Gretna Campbell who you studied with at Yale. What was it like to study with her there?

KS: Yale was an extraordinary place, a very exciting time—William Bailey was there, Lester Johnson, Mel Bochner, Andrew Forge, and Bernard Chaet. However, this was a boy’s club. Natalie was there some but Gretna Campbell was the only full full-time woman. Every time Gretna came into the studio it was to bring you a miracle, I’ll never forget this, she walked into my studio with a Bruegal book and flipped to a page and you probably know the painting there’s a figure and looks like his falling out of the painting and he is pointing at the back of him and there is a guy in a tree, do you know this Bruegel?

The Peasant and the Nest Robber 1568 Pieter Bruegel the Elder 59.3 cm x 68.3 cm Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

It was like a key in a lock that turned, and Gretna always told me that if I ever got my handle on space, I’d go to the moon. She said that where it’s happening, but I couldn’t get a handle on it. I knew I wanted it but I didn’t know how to see it, I couldn’t do it. And Bruegel was the key for me and that particular painting. I’ve never forgotten that painting. That’s how marvelous she was, she’d come into your studio and you’d be struggling, trying to keep your paint clean or something and she would give these little helpful hints like put your medium in one of those plastic squeeze soap bottles. and your like, “really?” “I’m at Yale at you’re telling me about soap bottles?” She said 20 years from now you’re not going to remember what Mr. FuddyDuddy said but you’ll have clean medium! It’s true, all of her tips about making paintings was enormously generous, humane and to the point. Like I say, she brought me miracles.

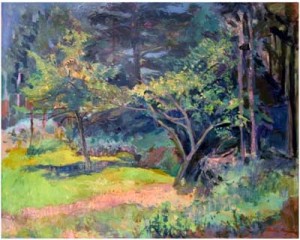

A professor, once came into my studio, I was making landscapes then-I’ve always been a representational painter— I had a big Birch tree in the painting, my paintings are always big, and he said “this object event over here…” I said you mean the Birch tree? No! this object event. I asked “are we talking about this Birch tree”? I didn’t know what an object event was and so blah,blah, blah…

So then next crit, in walks Gretna and says “what a beautiful Birch tree”…(laughs) and it’s not that this teacher didn’t have a point, it was important to see it as not a birch tree but Gretna believed in the importance of naming things. Gretna would recognize and take care of the personal connection, the actual love you had for the objects you were choosing, for the things you were trying to make. She never forgot that this was me trying to communicate to you and always recognized that as a kind of generous act.

LG: You stated that your paintings are always big, why is that?

KS: Because it’s a one-to-one ratio with me. I’ve gotten a lot of crap about the size of them but I make small prints, small reliefs, and lots of small stuff. I’ve tried but I have no interest in making small paintings.

LG: Do you see the large size as monumental?

KS: It’s a one-to-one relationship, like sitting here talking to you. I don’t have to have a ladder. These are my rules—so I can move the canvas myself, I can get it around the stairs, and that it’s on a one-to-one.

LG: Your paintings are big but the space is limited, constricted—you don’t have enormous vistas, the space is clearly defined and thoughtful space but it’s like you could only fit so many people into the painting, like in an elevator or something.

KS: I haven’t really thought much about that but I think of them more as holographs. They have to behave as shape… and to take something off the canvas I actually have to take out a permit. To have an arm be cropped, I have to apply for a permit. It’s such a serious thing to me to break my horror of elements going outside the boundaries of the canvas. I do it but only very cautiously because I think the minute you break that thing it’s like you bleed energy. I think that the more you crank down on it, the more taut it gets, the more it pounds the energy, to feel the force of those connections and shaping.

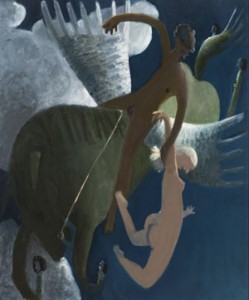

LG: You mentioned before about how important the composition is in your work where the subject in the painting as much about the composition as it is about anything like the story or myth. I know that’s probably true with most paintings but I’m curious to hear more of your thoughts on this. Your compositions are so intriguing and thought provoking.

KS: Well I like telling stories, they are important to me, the myths are a later in life development. The stories used to be personal but then I tried to turn them into something universal. At a certain point I took universal stories and tried to personalize them. So I now start with a story we all know. Some people don’t know myths, and I don’t know them very well either, believe me, I don’t know them very well. But I start with a story, boy meets girl, random stuff happens and you didn’t deserve it. Biblical stories are different are more like morality plays, myths are really trying to explain the cruel randomness of just trudging through your life. I think Bible stories are always like “you are bad so this happens” almost without exception, nobody’s bad in myths.

So the stories are important, myths are a universal telling or explanation of something that’s random thing and that’s just the way life goes, the random thing, so I like that. And that’s developmental—I’m at a certain age of my life where things happens and it’s not because I’m crummy, it’s just what happens.

LG: So you’ve never done any Biblical stories?

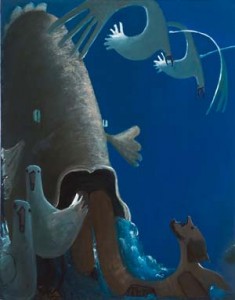

KS: Yeah I’ve just finished Jonah and the Whale, the old testament are better because God in the Old Testament is awfully random. Do you know what I mean?

LG: They are probably more directly connected to the original myth, like what Joesph Campbell might say about the connection from the Bible to pagan or other ancient myths.

KS: Yes they are all connected, so the stories are stories and then I particularize them or personalize them. Instead of trying to take a personal story and turn it into a universal truism, I take a universal truism and try to personalize them. Again and again, artists of mid-career to late-career do that. Lennart Anderson, his Idyls, you know he didn’t do those until sort of later on.

Composition is the delivery system, there are lots of different aspects of how the painting delivers its message. You need to have the horse firmly in hand or else you can’t do it. Composition helps me contain it and release the message in the way I want it.

LG: When you’re saying contain it, these forces, do you mean like a sense of balance of forces or weight? When you look at Titian or Rubens, they use various formal compositional theories and mathematical structures like the golden section or similar. You have your own, more intuitive balancing structure but perhaps done in a similar spirit as the old masters? Can you say something about how you think about this?

KS: I think of the canvas as an arena… I set up my rules, something going to happen and the painting must resolve, I don’t leave them hanging. Everything has to be accounted for, every piece of the painting has to be introduced and informed and in working order with the rest of the painting. There is nothing casual about the components of my painting’s relationships to everything else. There is nothing that I’ll let go. It’s like cat’s cradle and I’m in charge. How do I know if it’s working or not? It’s not a plan as if I were dismembering a bomb or something. You can read all you want about composition but until you’re there and you have your hands on; you can’t know. So it’s only in knowing the painting, so I feel my way through and I trust that. That’s my job.

LG: You do your job incredibly well. I’d like to ask you about your morning Facebook albums. I’m really curious about it as it’s had such a big effect in how many people start their day. I love how it get’s us thinking about the interconnectedness of the painting language, how so many paintings talk to each other as well as getting the painters themselves to literally start talking to each other on Facebook.

KS: I think we painters are a tribe and I think that a lot of painters are terribly isolated. Some or a lot of the reasons they are doing this, not just that they are visual thinkers but that they don’t interface well in social endeavors. So here we all are in our studios, wishing we had the life they have on commercials, so Facebook comes along and gives us an opportunity to communicate in our jammies with our coffee, safe. You sort of feel like I can do this, it’s just sort of built from there.

What I want to talk about to other painters is what I’m looking at. I’m working on a painting, I’ve got maybe something’s not going right, I’m looking at Titian cause Titian did it right and then I’m thinking that reminds me of that Renoir, Renoir must have been looking at him and then you go to look at the Renoir and then you realize there’s a cave painting and then all of a sudden I’m all over the map, I’m talking with all these other troglodytes in their jammies and coffee, and there saying no that Renoir doesn’t remind me of that, look at this and then all of a sudden my little tiny world becomes enormous.

All of a sudden I’m sent paintings from China and the world gets bigger, and then you say well, it’s Facebook. But that’s not all it does, because when I actually go out and I meet Facebook people I know them. You know it’s not like a dating service when you meet them and you think, eeww, oh god. You know we’ve talked maybe if it was a dating service it wouldn’t work but because we’ve talked about paintings, we’ve made our position clear; we actually do know each other. So it translates into the real world. So by doing these albums, and by problem solving or thinking out loud to my tribe, they have responded because it’s a safe way to respond. In doing so it’s changed all our lives. I’m sure they feel the same way when they go to an opening, they feel a little less overwhelmed, a less like I don’t know anybody—cause now we do.

So I think it’s a really good thing and for me it’s changed how I am in the world. I’ve gotten teaching jobs, and until I did this and started to write about what I think—I didn’t know I could do that, I didn’t know I could talk about painting this way.

LG: Are there any situations where people’s comments/submissions piss you off in some way? That you’ll feel this is an inappropriate use of my album. How do you handle that?

KS: I delete them and back message them saying I deleted your post, you’re welcome to participate but not in this spirit. Then there was a big deal when I don’t want people to post their own paintings. There was a groundswell a couple of months ago that was awful. I don’t mind occasionally, that’s terrific but it’s just not the format for that. Put it on your wall, I will come, we will come— the tribe will find you. This works because we’re not invested in it on a personal level, it’s not a… I post on my paintings on my wall if I have a show up or something happens then I use my wall to post it but not in that morning album format.

LG: What about someone who might, for whatever reason, post many, many paintings on a particular album?

KS: That’s another thing I’ve had to back message people about. I post three painting qne the maximum you can post is three.

LG: That sounds like a good rule to have, I didn’t know about it.

KS: If it happens one day I don’t say anything but if it’s consistent then I will step in. I don’t want to curb the excitement that somebody feels when they’re on a roll. So if you have one day that’s fine but the couple of people I’ve back messaged about this if was a consistent thing.

KS: There are usually a million different points at which my albums match, there will be a compositional thing, there will be like a frontal, there will be three quarters, there will be a certain scale, they should try to match them on as many points as possible, its not just subject matter. I had one the other day where trees marked space.

LG: I remember that one, a very good one.

KS: It wasn’t just about trees, it was trees that were making space, in their placement they were making space. So when people were posting stuff, some of them got it and came up with incredible things and some just posted generic forests. But I don’t care about that.

LG: So tell me this, if you could get all the points of connection (between the three paintings) possible that you could win a Kyle Staver’s Morning Album t-shirt or something?

KS: (Laughs) there is one woman who always back messages me and asks if she’s getting it… I thought that was very sweet and said yes that was a good (observation? – audio not clear) I’m saying this to you about the points I don’t make that public, I haven’t said that. I don’t make rules except the only you can’t post 5 thousand images and you can’t post your own work. So it has a life of its own, I have rules but I’m not a very good enforcer and it’s fine. There are a couple of times I’ve deleted paintings but it had to be so in my face.

When I have a good album there is nothing better. I have a great one for tomorrow; I’m a day ahead. A cartoonist once suggested to me that, to always make them a day ahead. I used to make them every morning very early and it takes me up to 45 minutes or so. But now I make them the day before.

ArtPneuma Video Interview with Kyle Staver Filmed by:

Sunny Miller (http://sunnymillerphoto.com/)

Feb 22, 2012 Interview by: David Campbell,Jay Walkerand Alison Stigora

Filmed by: Sunny Miller

Wonderful interview! I had the pleasure of seeing Kyle’s work for the first time at Artprize last year in Grand Rapids , Michigan. I was intrigued at first sight. I hope to see more on my next trip east this fall. Really enjoy the work.

thanks,

John

http://www.johnjdonnelly.com

Kyle,……..I love the interview and the video. It is emotional for me to hear another artist,..to hear you – talk about what it is like to be an artist in the world. You nailed it. How we must invent the whole thing – the life, the way we will get this done in this world that does not quite get it. And, I love the part about being able to “see”. I also teach (privately one night a week ) and it is exactly the ability to see, that makes the teaching possible. No amount of technical knowledge about paint or “technique” or methods, etc will matter at all if you cannot “see”. And finally, for me,..your work occupies the space between Avery and Bonnard, two of my favorite painters. – Scott

Lucid & deeply resonant for me! Appreciated learning more about Kyle’s painting process besides her very smart art image threads on Facebook.

Wonderful interview and video…just great.