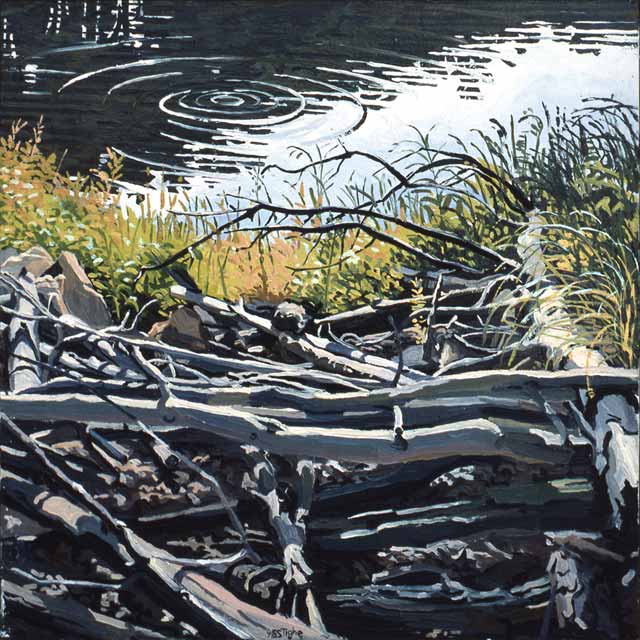

Ken Tighe Salt Springs 2009 38" x 48" oil on panel click here for a larger view

I am fortunate to have known the extraordinary painter Ken Tighe since the late 80’s in Boston when several former students of George Nick as well as George himself would meet every few months for a number of years. We would share a pot-luck dinner and sit and talk about our work and art in general. It was thrilling to see what everyone had come up with since we last saw each other. I particularly looked forward to seeing Ken’s latest paintings as the intensity of his dedication and vision often made for unforgettable paintings. My appreciation of his work was renewed recently with the launch of his new website I decided to speak with him by email in the hope he could share with us some details about his background, process and thoughts about painting. I’d like to thank Ken again for agreeing to to this interview and for his time and energy with writing his answers.

Larry Groff: You studied with both George Nick as an undergrad at Mass Art and Neil Welliver for Graduate School at University of Penn, two giants of painterly realism and also both renowned for being great teachers. How would you compare their overall approach and philosophy in teaching and what aspect of their teaching influenced you most?

Ken Tighe: I feel so fortunate to have experienced the teachings of both extraordinary men. To best compare and contrast George and Neil, I might do well to share some of my experiences and recollections.

I entered my junior year at Mass Art in the late 70’s. After a number of confused and uninspired first weeks; a dashing, mustached, instructor wearing jeans and a turtleneck under a button down shirt approached my studio and asked who did the paintings on the wall; they were mine. He replied…“not bad”. He then asked who I was studying with. After telling him, he responded with an almost disinterested “uh- huh”, paused, and proceeded to tell me that if I were to make him my instructor he could put me ten years ahead of the game in two years. What a pitch! Well, I couldn’t refuse the offer, and didn’t. I was flattered, intrigued, and excited to begin working with this instantly magnetic figure.

George can appeal to a painter on so many levels; not only with the adventure and romance that made even the hard work of painting look appealing; but also through stimulating discourse. One of my great personal joys is listening to him speak about painting. He leads by example, works constantly, and is passionate and curious about everything; he makes you want to paint. He is in perpetual motion, both physically and intellectually. But, to get the time of day with George, you’ve got to do the work; he makes no bones about the hard work and sacrifice involved with being a painter. In his studio you had to prove yourself by putting in the hours; then he would begin to engage you on other levels. This made sense to me.

Nick was telling me to get out and start looking; to measure, draw, paint; to get it done and don’t waste time…I was 20 years old with Kerouac in my back pocket. The blue collar poet approach was right up my alley. The tools and direction were intriguingly (and deceptively) simple, the mentor larger than life, and the lure of painting and engaging with the world on these terms undeniable.

Salt Springs, Four Dudes 2010, 16″ x 48″ graphite on panel

Broadmoor Sluice, 2010, 16″ x 16″ oil on panel

Broadmoor, Little Falls, 2010 12″ x 12″ oil on panel

Moving on to the University of Pennsylvania was a dramatic culture shift for me. Artists stayed to themselves, and Welliver could be distant; like Oz behind the curtain. I was given a studio and a key to the building; you wouldn’t see Neil for weeks on end. He lived and painted in Maine and would show up every few weeks or so to check in, and hold individual and group critiques.

Initially, I felt Neil’s presence in the cadre of renowned artists and thinkers who collectively presented a view that was copasetic with how he wanted to guide you. Visiting artists would show up and make studio visits. It was a who’s who of contemporary American painters. I was fortunate to meet some extraordinary artists; Alex Katz, Phillip Pearlstein, Jack Beal, a brief visit with Alice Neal, Janet Fish, the wonderful painter, photographer, and film maker Rudy Burkhardt was in residence, and his wife the painter Yvonne Jacquette was a regular. I was particularly impressed by Janet Fish and Yvonne Jacquette. Unable, at first, to make complete sense of my experience, I listened hard, took in as much as I could, and proceeded to do what I’d always done and knew best; I left every morning to paint.

I got to know Philly fast and made lots of paintings of the shipyards, the Schuylkill, views from on and below the amazing bridges that span the Delaware River; the Ben Franklin was my favorite. I would do one or two small paintings a day, along with working on something larger and more long term, and bring them to my studio to reflect on the work and the days experiences at night. If the weather wasn’t cooperating I would stop by the market and buy some fish, head to the studio and paint a still life; or maybe have a friend sit for a portrait. The importance and meaning of my work was still largely about the subject, the place, and the experience. But I was painting a ton, making wonderful friends, and having the time of my life.

I remember showing up with at least 30 or 40 new paintings of all sizes to the first group critique. I was nervous and I figured there was strength in numbers. It was my first meeting with Neil and it was no tea party. It was the first of a lot of head butting. Despite my effort he expressed his displeasure. He told me that he would need to break my work down completely and start all over again with me. It was not what I expected. I thought that people would react positively to my hard work and enthusiasm. The focus on the work I brought to that first critique was about what I should stop doing; an emotional downer. I felt that my instincts were true and should still be followed. I loved to paint, and my appetite for work large. I continued to pour out the work, listen hard, and process what I could. Still, I always felt out of sync and remained a bit of an outsider.

At the end of my third year during my thesis exhibit, Neil asked me to meet him in the gallery. We sat on a bench surrounded by my work and had a wonderful talk. He could be kind and fatherly; he was that day. He was supportive and encouraging. I remember him telling me (and I’m paraphrasing) that I must be more conscious of the flat issues. He asked me to consider the synthetic nature of the painting process, and that to remember that I was making paintings, and even at its most intuitive and observant, that process was a contrivance. The painting had a voice that I must listen to more. It was hard to reconcile my thinking at the time with what he was telling me. It felt beyond me, but I filed it away and kept it at the ready.

dried creek, 22″ x 22″, 1985, oil on canvas

It was 1985, and for the next year after leaving Penn I was terribly confused, and my painting was floundering. I started a hundred paintings I had no desire to finish. I could not satisfy the “why” of painting anymore. I was boring the hell out of myself so profoundly; but I was also physically and emotionally exhausted from the eight years of my combined Mass Art and Penn experience. I needed a respite, I needed to regroup. One bright spot was a trip I made to visit a friend at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. I was blown away.

I applied, and was accepted to the Skowhegan School for the summer of 1986. It was a transformative experience in an extraordinarily supportive and nurturing environment that helped me make my first real headway in processing, understanding, and using in a practical way all that I had been learning.

George was my bedrock, but I began to realize how much of what Welliver and I had fought over had seeped in. The talks with Janet Fish and Yvonne Jacquette were starting to solidify and had to be worked out in my painting. You can only understand when you are ready to understand. Hard work gives understanding a place to thrive. Skowhegan was the perfect place for it to happen.

I made a series of small paintings on the Carrabassett River that used the rock formations as a catalyst for abstract composition. I consciously tilted my gaze downward, removed the horizon, and avoided over description of the object for the first time. I did two paintings a day on the river. I painted very quickly but with great focus and concentration. It was the most complete painting experience I’d had up to that point; as I started really listening to the painting itself for the first time. I was painting with great alacrity infused with fresh enthusiasm; being in that specific place was important, but now it was for different reasons. It was the first time I understood and expressed with clarity that the painting was not just a record of the adventure. I like what Mark Rothko said, “a painting is not about an experience. It is an experience."

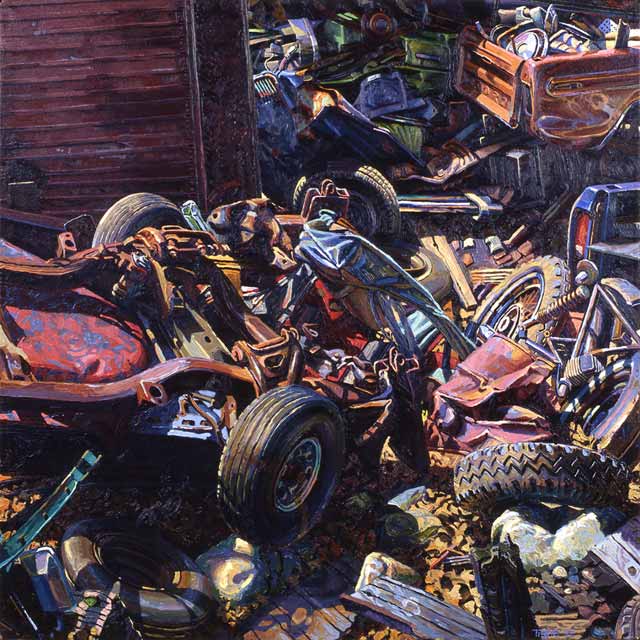

boneyard, 1992, 30″ x 30″, oil on canvas

LG: In many of your salvage yard paintings, rock series and still-life’s you engaged with fantastically complex subjects yet there is remarkable unity and visual clarity. There is an “over-all” approach to some of these compositions that bring to mind Jackson Pollack’s abstract expressionism and seem more about the gestural flow and rhythms than just an accumulation of highly rendered details. What sorts of things do you think about in approaching the composition like in the Broadmoor rock paintings?

KT: rock paintings?

There are endless elements in the world that inspire me and act as a catalyst for making what I think would be a good picture. I am currently working on a painting in the middle of the woods, where I am surrounded by the dance of filtered light and dark as it moves down and around, and through the layers of trees as they recede into a morass of seeming confusion. The woods are such a multi-directional, almost multi-dimensional environment; it is wonderfully disorienting. Being bathed in the diffused and filtered light under a forest’s canopy can feel like being underwater.

Also, the changeling quality and kinetic force of moving water or clouds, the surfaces and colors of drifting heaps of tossed metal and rusty scrap, or how the rambling tumble of rock formations cut space like ripped paper. I love the role light plays in how more distinct or less distinct the world can look, and how you decide where one object ends and another begins. I enjoy working with and responding to these kinds of trickery.

I prefer compositions without a primary subject or center of attention. In the paintings you mention I offer little or no clear hierarchy of subject, mark, line or shape. That might account for (as you called it Larry), the “all over” composition of many of my paintings; “no beginning and no end” as Pollock said. I like to make paintings whose painted content also references all the possibilities beyond the boundaries of the actual painted image. A friend once referred to my paintings as “maximalist”. I like this description; it perfectly describes what I am not; a minimalist.

I also choose somewhat chaotic subject matter many times as a way to distance myself and the viewer from understandable or familiar points of reference. For example, I often avoid working too obviously, or at all, with the element of horizon. For me it is frontloaded with symbolism that can lead to unwanted assumptions made by myself and the viewer. Compositionally it can be domineering, predictable, and emotionally it invokes nostalgia and can draw the viewer in with sentimentality.

I did a series of flower paintings a number of years ago that were meant to sequentially remove or alter questionable or unnecessary elements; a kind of purging exercise. To deal with the horizon, I started to engage it more as a visual punch line, as a literal scratch through the paint; reduce it to a symbol. Interestingly its impact didn’t seem to wane. Draw a line horizontally from left to right across a page at any point from top to bottom. Do nothing else; the imagination will eagerly supply the rest. Knowledge of ground and sky, foreground and background, becomes hardwired in all of us. Removing an element like the horizon can take you out of your comfort zone and push, or at least nudge, the viewer to engage with the surface and view the painting with a different set of critical tools. For me that is the activity that engages the “now” of things. It keeps the experience vibrant and visceral and full of the present.

It’s funny you know, I’m not trying to single out or pick on any one element; It’s really about starting points. I think of, for example, young children when they compartmentalize and separate the land from the sky in drawings with no awareness of the space that separates them. They have yet to intellectualize the connection in what’s called the “schematic” stage of drawing. It’s a fascinating stage of development. It’s the last time when the world is seen and drawn without the knowledge that it doesn’t relate to how the world actually looks; the last time they will be unaware of their abilities. Eventually they mature and make a less naïve, less spontaneous decision about how the world looks that’s informed differently; from personal, external, and other changes and influences. I like to think that I can enter a painting from a less informed, or more naïve vantage point and be more in control of the knowledge gained while building it and in the experience of viewing it. I try to use elements that hold and engage you in surprising ways for as long as I can. I like to start in places that our eyes and minds may not find usual. I look hard at the overlooked.

LG: What is your process with your current paintings? Do you generally paint on site or do you also paint in the studio from studies or some other reference?

KT: I always paint on panel, use mostly round brushes, and a higher ratio of medium to pigment for a more fluid, almost syrupy paint consistency. Working on panel gives me a hard surface to lay down areas of pigment. All of my mixing takes place on the palette; I don’t mix or blend on the panel. I work in a kind of “drawing drip”, as I layer in color next to color, and color over color, so the layered juxtaposition of distinct tones work in unison to best inform the larger image. Larry, this technique, and the fact that I keep my paint at a fluid consistency, may relate to the gestural quality of paint movement in my work you made reference to earlier.

I paint both on site, and in the studio. I work in concentrated bursts, always trying to nail a section down on the first try whether it’s in the studio or on site, from life, or another source. If at first I can’t completely resolve a part, I’ll get it in the next pass so the eventual resolution of a painting is a layering of solutions that hopefully feel immediate…that can retain a just painted look no matter how many passes I make. I approach my work with the mindset that I will get it the first time around. I like what Helen Frankenthaler said, “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image”. “Looks”, of course, is the operative word there. It may take two or twenty tries to “get it right the first time”. My goal, whatever my source and number of attempts, is to present you with the opportunity to experience for as long as you want the sense of a moment, not a moment of experiencing timelessness.

Keeping that in mind; when working on site I choose to make a painting within the parameters of a certain time of day, working through the challenges provided by the limitations of fleeting light. With little time to react and respond to an observation you have to muster every bit of focus and facility to fulfill all the promise of that complexity as quickly as possible. I paint where the subject matter can become so confounding and gloriously confusing that my initial feelings are of utter incompetence; a good description of my preferred starting point. The thrill is in fighting your way out of that “paper bag” successfully.

When working from a more static source, like photographs or a still life in the studio it can become difficult for me to avoid a kind of “mapping” of information that comes from spending too much time on things. I work hard to avoid this. In studio I’ve reconciled with the fact that I can’t recreate the unpredictability of nature when painting on site. Without the demands of attempting to capture time in the multitude of singular moments that occur as light changes and time progresses there is the danger of over describing. So, I at least try to control the time spent on a portion of painting to prevent this. To maintain a sense of immediacy both personally, and in the look and feel of the painted surface; I work in shorter slots of time, on small sections of the painting, and try to complete these areas in single sittings. I won’t return to it unless absolutely necessary; just as I do on site.

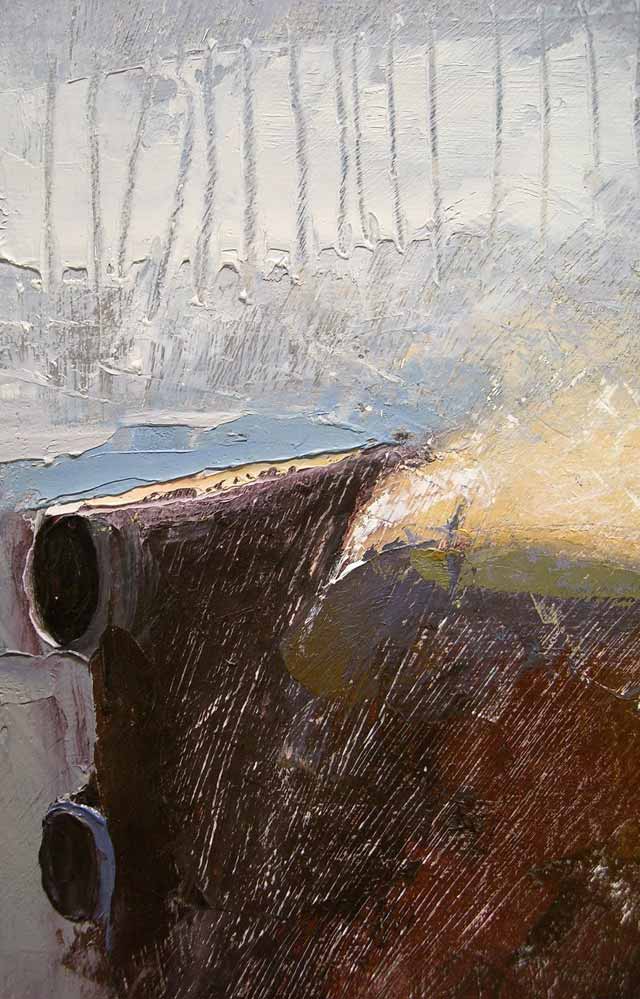

Specter of my Childhood Buick, 1999, 20″ x 24″, oil on panel

Specter of my Childhood Buick (detail)

I think people who look at my paintings respond to lots of issues that have to do with my process. They have strong feelings about the places I describe, and on one level believe that’s what the paintings are about. They also seem to respond to the “optics” of the experience. Meaning that being up close to the painting and being aware of the mark making and textures is very different than being 5 to 10 feet away and taking in the spatial illusion as shapes and colors lose their independence and work to form convincing illusional alliances. I often see them moving in close and then backing up multiple times. It’s wonderful that they seem to be enjoying both places, but it’s the transitional experience that really seems to be important. It reminds me of those “magic boards” when you were a kid that would change from one image to another as it was shifted in your hands; remember those? Holding it at that pivotal point and experiencing the anticipation as it shifts between images was maybe the most exciting part. Anyway, for me it means that I can successfully engage them, almost simultaneously, on both levels.

As far as choice of subject goes, I absolutely appreciate the natural or unnatural beauty of a forest or a junkyard, and have strong personal feelings about the intrinsic meaning of the places I choose to make paintings. Those thoughts are important, but mostly incidental and extrinsic to my reasons for making paintings. Like all those years ago on the Carrabassett River; or in the recent Salt Springs and Broadmoor work; I am appreciative of the beauty of the location, but largely unaware of it when working; and not concerned with conveying that through painting. I am in awe that these conditions exist to fulfill my needs as a painter.

LG: What gives you the greatest pleasure in your painting and what do you need in order to get to that place?

KT: When at the height of the most fluid communication with your subject, as you engage the world armed, almost humorously, with colored muck, brushes, and a flat piece of wood; still you jump in, like Don Quixote tilting at windmills. There is wicked pleasure in that.

The creative act is one of the few human activities that can allow you to experience and then share the result of an altered state of consciousness. For me, being an artist, making a painting, is the mode of expression that holds the most potential for me to mix the aesthetic mortar that fills the gaps between all the separate chunks of personal and cultural meaning. It is the activity that completes the bond and makes the life experience a more solid, and continuous surface.

“For art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity or perception to exist, a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

dom al horno, 1997, 12″ x 18″

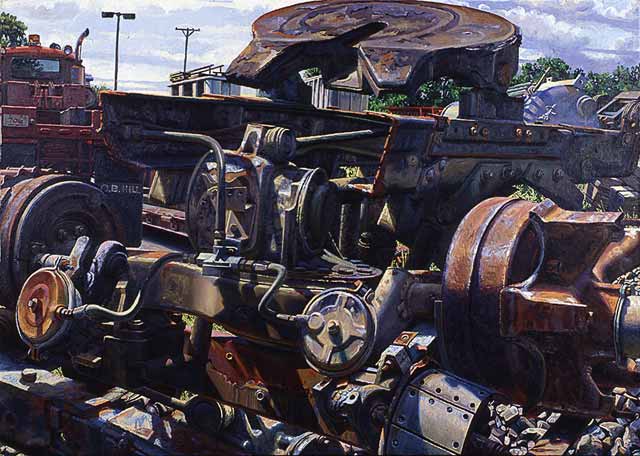

o.b.hill, 1993, 28″ x 40″, oil on canvas

Guardians, 1992 oil on canvas, 36″ x 36″

Rt. 135 salvage, 1997, 16″ x 48″, oil on panel

LG: What is your favorite art book?

KT: I’m in the middle of a book titled “Tom and Jack” by Henry Adams. It’s a fascinating look into the personal and creative relationship between Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock. Adams provides entertaining and informative insight into each artist; first rounding them both out individually so as to better understand the complexities of their relationship. He then presents a persuasive argument for Benton being the prime influence, not only in the compositional elements of Pollock’s drip paintings, but as one of the reasons Pollock was able to get to that point at all. It’s a great read!

LG: You’ve taught at the Walnut Hill School for the Arts in Natick, Ma, a private school with a very good visual arts program, for many years. How has your teaching influenced your own work?

KT: Yes, I’ve just completed my 25th year of teaching in the Visual Art Department at Walnut Hill. It is an amazing place that engages and inspires high school age artists from all over the world to diligently study and develop their craft and learn about themselves as young people and artists.

The biggest influence on my own painting in regards to my teaching is the responsibility and accountability I feel for the advice I dispense to young artists. I can’t teach painting from memory; it’s critical that I be a working artist who can give to the students the best of my accumulated and current working knowledge as a painter. They will hopefully see and experience in me even a little bit of what I’ve been fortunate enough to receive from the amazing creative mentors in my life.

kermits lift, 1993, 40″ x 40″, oil on canvas

mr. sunshine, 1996, 24″ x 24″, oil on panel

all the players, 1996, 24″ x 24″, oil on panel

elevate me mama, 48″ x 48″, 1996, oil on canvas

Very well articulated paintings and words. The river bed ones are knock-outs…I’m sure the reproductions don’t do them justice, as there seems to be a lot going on with the paint handling and scale. Thanks Larry, and keep up the good work Ken!

It is amazing that these are done so quickly on location! Ken you are a wonderful painter! Your work has an uncanny quality to it that feels earthy, dark, serious and celestial. I am so grateful to both of you. Thank you Ken and Larry.

I have an early painting of his(1985). It is good to see him still working and progressing. Good work!

My Uncle owns an art studio in New York City, please send me an email direct so I can send you my number and we can talk.

Francis and Noel; thank you for the generous comments regarding paint quality, process, and the “feel” of the work… (You know,,I am reminded that the large Salt Springs painting was made entirely with an angled painting knife). Also, Jen, I am fascinated that you have a an early piece of mine; I’m curious to know which it is? If you can let me know please do! …and David, your comment is certainly intriguing! For anyone who wants to contact me my e-mail is on my website. Thank you all!

Great interview that provided a revealing look into the process.

The painting is an apple, a bottle of tequila, and a bottle of lime juice. They are on a dresser with a mirror. I liked how you used color for the glass bottles. When I bought it, I was reminded of wheat fields and the bright crisp colors of the west.

I enjoyed reading the interview and learning the insight behind the pictures. The time I was involved reading the interview and looking at the art carried me away to another place. I felt relaxation and remembered glimpses into my childhood. Ken, thank you for transporting me away from my hectic life for a sweet period! I will look forward to following your amazing career!

Jen; I am pretty sure I remember having a conversation with you all those years ago about how important the colors were to you in that painting. That painting was made in the dead of a cold New England Winter; I’m sure at the time that those colors were a reminder to me of a warmer place! That piece is on my website as well.

Sheila, thank you for your very kind and thoughtful remarks! I am flattered that my work could provide a relaxing point of departure for you. I am reminded of a couple of quotes…

“Art is the only way to run away without leaving home”.

Twyla Tharp

“A good painting to me has always been like a friend. It keeps me company, comforts and inspires”

Hedy Lamarr

I am so grateful to you for sharing your mental and material process. Also I appreciate reading about the over-arching process of your painting career so far, including the stalled period after graduate school. I’d like to share that I was a student of yours. Your lack of hipocrisy- walking the walk and not just talking the talk- was impactful. I am lucky to be able to say you were one of the very few “amazing creative mentors” in my life.

I have always wondered why you chose the scenes you chose: “…the subject matter can become so confounding and gloriously confusing.” Gloriously confusing! These are scenes and subjects that would most likely drive an average painter to the mad house. Yet your paintings emanate a sense of pleasure (as well as pain) in their making.

You are unafraid to attempt the impossible. This is a value you taught in class, though I think it takes a very strong will to actually do. The concept has somehow been absorbed to a degree and strengthens my own work immensely. For this I thank you.

I just had to share a coincedence. The salvage yard painting “o.b. hill”, with its name lifted from the mudflap of the truck, got the name from my uncle’s trucking company. Oliver B. Hill ran a trucking company in Natick, Mass. He passed away a few years ago, but the company is still family owned. O.B. (or Obbie as we called him) was one of the most magnetic, full-of-life people I’ve ever known.

Anyway, I love Ken’s jumbly paintings with no particular center of interest. Your eye moves around from one section to another, taking in the whole composition.

Jonathan,

I am blown away by your message. I made that painting over an entire summer spent in the back of the O.B. Hill yard with the railroad tracks to my back. I never met Oliver, but your description of his jovial nature makes sense, because it must have rubbed off on his employees. They were a great bunch of supportive guys who were happy to have me there.

My tale is this. I was halfway through the painting (had to be late July), when one afternoon I showed up to set up my easel and get to work. Well, the massive truck axle you see in the painting had been moved to another part of the yard. I must have looked a bit forlorn, (standing there scratching my head trying to figure out what to do), because one of the guys came by to ask what was wrong. I told him, and within minutes he had hopped in the fork lift to retrieve the huge piece and gingerly place it back on it’s perch. I can still hear him shouting to me as he moved it around; “is that OK?…how’s that?…does it look the same?” I will never forget my great experience working there.

Thank you also for the wonderful comments about my painting!

My daughter was a student at Walnut Hill in the early 90’s and my husband bought a painting from you. “George and Sophie’s truck ” painted in 10/84 while you were at the University of Pensylvania.

We have for enjoyed having it all these years. So glad to see you are still teaching at Walnut Hill.