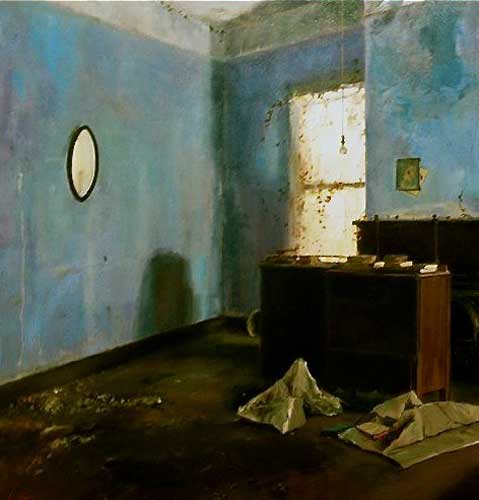

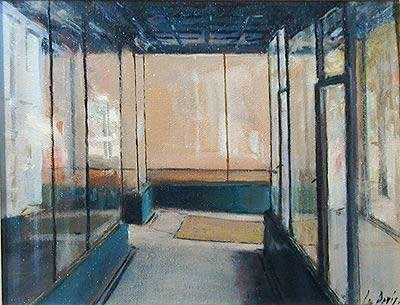

Julyan Davis , Abandoned Mansion II, Oil on canvas 36×38 inches

A realist searching for something that’s real

I recently was introduced to the work of artist, Julyan Davis, an English-born painter, who studied at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London and now lives in Ashville, North Carolina. He recently had a one-person show at the Greenville Museum of Art and shows at the Helena Fox Fine Art Gallery in Charleston, SC, The Greenhut Galleries in Portland, ME and has shown work at a number of galleries and museums in the Southern US and elsewhere. I was intrigued by his paintings of abandoned Southern mansions and his other unique views of the South and was interested to find out more about his process and thoughts on painting.I would like to thank Julyan Davis for putting the time and effort into this email interview.

One quote from Julyan Davis’ generous interview I wanted to draw attention to from the beginning as it echos an important part of why this website exists

“We all need to be educating the public like crazy! In the Dark Ages, people were as likely to follow animal tracks as use the empty Roman roads. The history of art is similarly full of amazing acts of forgetting, of losing mastery. Twentieth Century art was often disdainful of public interest. We cannot expect the public to wade through so much art today, in so many forms, and arrive at our work with complete understanding. Education is essential.”

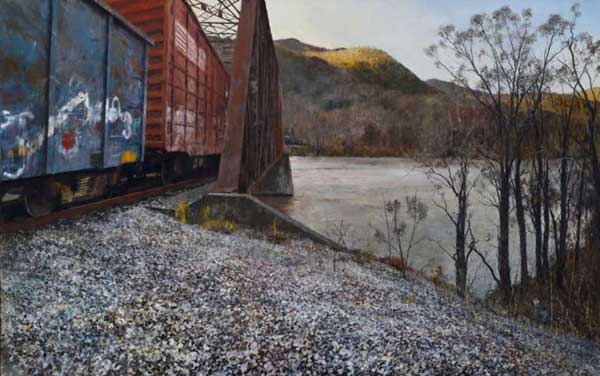

Larry Groff: You came to the United States from London for the first time in 1988 to live in Alabama and North Carolina. I’m guessing that part of the appeal of the American South, is that you can still find a visually authentic urban landscape, large areas still unspoiled by strip malls, development and tourist attractions. In this environment you paint scenes with strong abstract qualities that are also evocative and might suggest a narrative but don’t seem sentimental or nostalgic. You seem to be a realist in search for something that’s real.

Julyan Davis ‘A realist searching for something that’s real’. I like that. You have noticed in my work that I am very wary of nostalgia. I spent a lot of time growing up in Bath, at the edge of England’s Cotswolds, and the whole place is gloriously beautiful, manicured and charming. (No wonder Thomas Kincade loved it). My work is a reaction against all that universally accepted beauty, I think. Just like a novelist seeking the hidden story behind how things happen, so I at once responded to the untidiness of certain aspects of the American South—the way people’s yards are scattered with the evidence of their lives. England is too small. Everything is tidied up in competition with the Jones’s next door. America lets it all hang out. How did one visitor describe the brick facades of cinderblock stores to me? ‘These places look like a person dressed for dinner, who has forgotten to tuck their shirt in behind.”

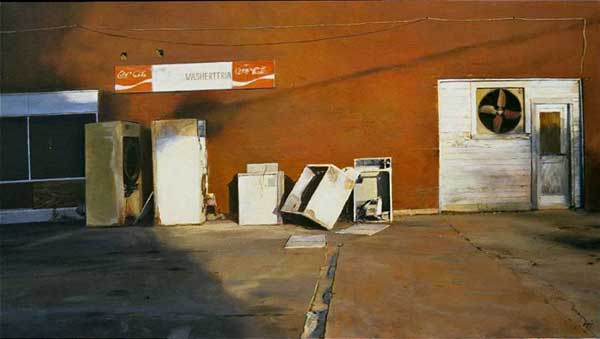

Mr. Waffles (study) Oil on canvas 16×26

That kind of unintended display brings out the realist in me—the nosy investigator of human details. I’m aware that this preference, this ‘nostalgie de la boue’ has not made life easy for me. I would have much less trouble selling more acceptable wear and tear: cobbled streets in Charleston, villages in Vermont. I remember a dealer asking, “Julyan, this is a lovely landscape. Could you just paint out the telephone poles?” “But the painting is about the telephone poles,” I replied.

Maybe it’s just one kind of European response—the same way British director Ridley Scott was so entranced by phone lines in ‘Thelma and Louise’. Other Europeans say America’s lack of a visible, long-term history makes it soulless. This makes them uncomfortable. I see quite the opposite—America’s disregard for its all but oldest past, its constant need for the new (while the evidence of the fifties, sixties, seventies is left to fall apart ) make it unbearably soulful! The empty storefronts, diners and houses are a declaration of our ‘little lives’, our brevity. I love it.

Abandoned Farm Oil on canvas 24×24

Bank Interior, Newbern, Alabama Oil on canvas 30×24

Green House Oil on canvas 24×30

LG: Please tell us more about your interiors. You’ve painted a number of abandoned mansions, farms and commercial buildings, sometimes suggesting something out of a Flannery O’Connor story. I imagine you have some interesting stories about encounters with surprised people or animals? Do you usually work from observation in these interiors?

JD: The interiors just evolved. I had painted a lot of buildings from the outside (and yes, I have been approached by people carrying guns, or harried by marauding dogs), but one day I got the chance to view an antebellum mansion that was about to be sold. The owner had moved out thirty years before and left the place in disarray. There was still food in the fridge. I enjoyed doing these paintings and people responded.

I had an interesting revelation about the interiors recently. I have a show at the Greenville Museum at the moment, and it is hanging adjacent to their huge Andrew Wyeth collection. His influence on me in my adolescence suddenly hit me. A family friend had a book on Wyeth and I am sure now it was his work more than any other that drew me to the details of worn and dusty interiors. My grandparents had run a small boarding school and closed up most of it when they retired. The derelict classrooms and dormitories, falling plaster and cobwebs, were some of the first things I painted in oils.

The interiors are fun, and can be (with the owner’s permission to be there) a rather comfortable way of painting away from the studio. I am wary, though, of the work just becoming a record—taking device of subjects without a direct connection to me.

Encounters with animals? When I first came over, renting a place in Holt, Alabama, I had a hell of a time with a pack of wild dogs. Every day, as I went out to paint the abandoned steel foundry they would follow me down the road, snapping and growling. Learning to drive a car has helped a lot! My favorite encounter was painting out in woods of North Carolina, when at least a dozen turkeys finally gave up waiting for me to finish painting and fell like so many black umbrellas out of the trees around me. The strangest must have been two paintings for a Lobster-themed show up in Maine—nudes posing as mermaids, on a beach and a bed, each with a live, and restless, lobster.

Abandoned Mansion, Oil on canvas 38×36 Greenville Museum of Art

LG: I’ve read you paint nine hours a day, six days a week. Your work seems to be a mix of work done from life and the studio. Do you make studies from observation that you later work up in the studio? Can you tell us something about your process of how you go about making your larger works? Anything interesting or unusual about your palette or technique? What sustains your energy the most when painting such long hours?

JD: Nine hours a day, six days a week? Not any more. Being a part-time parent of a two year old has changed all that, and for the better. I am forced to be a part of life more often, rather than be a perpetual observer. What are my working methods? I enjoy working from life in every genre—portrait, nude, still life, landscape.

Painting in the landscape, I am often too ambitious in the size of my canvases, but this is because I do not like doing a larger canvas later from a study. I find I lose interest.

I should reconsider my methods! I paint fast, but I am often too skimpy with the paint for a painter choosing that process (of working larger in the field). Also, I love doing small paintings. I remember being very envious of the Stuart Shils paintings I saw up in Maine, and wishing the world had become used to me working only on small panels.

I have also found a way to use photography for certain subject matter. This began in America, in the South, because I liked painting a lot of things that provoked suspicion and little welcome among the locals. To be fair, I am sure it looks patronizing and judgmental to paint a person’s yard, or the three crosses they have set outside their trailer. It probably is patronizing and judgmental. Anyway, If I am not doing things that will fit on a French easel in a friendly environment, if I am doing an urban scene or something like, I use an odd system of working outside from photographic reference. This system began before I could afford a studio, but I still use it. I like a ridiculous amount of (indirect) light, and I like being in a light and time of day that mimics the atmosphere around my subject. I use a few regular printsfor reference, and I am guessing my short sight is a help. I tuck the image under my thumb on my palette and glance at it periodically. If I had better eyesight I would probably be confounded by the detail. For years my work has been quite realistic, but for a long time it was heavily influenced by artists like Bonnard and Vuillard, also Expressionism. That was perfect for including photographic reference, because I had much less interest in precise local color, tone etc, in fact I was always searching for colors and tones that were an emotional substitute.

I still rely on visual memory for such things, and still love to play with altering color, perspective, scale etc. I love to take a rather ugly color and place it in such a way that it is read by the viewer as something entirely different.

Gold Sofa Oil on canvas 40×36

My landscape palette generally consists of Titanium White, Naples Yellow, Yellow Ochre, Lemon Yellow, Cadmium Yellow, Cad Red and Alizarin, Cerulean, Ultramarine, Burnt Umber and definitely Black! I love to try other colors, though—an odd pink or orange, any yellow or blue. I’ll add a color to my palette for a painting or two, just see how it goes. I start all my paintings like some manic Expressionist—Beckmann or Rouault, lots of strong lines, intense color, then I calm down and apply most of the paint quite delicately. I hope to end each painting though with final vigor. Auerbach said something like, “A painting needs a damn good kicking to get it started’. I like to come up with something that also catches me off guard at the close, kick the thing out the door, so to speak. I may be a realist painter, but if I was able to visualize every single aspect of the final product before I began a painting, I would choose another profession.

My technique reflects my very inclusive attitude towards painting. I am loath to leave behind all the different techniques I have used. I studied Constable and Turner a lot, and still use a palette knife a great deal. I use bristle brushes, and sharp or flat synthetic brushes together. As with most artists, there are aspects of many schools of painting in my work. I enjoy working on panel, and heavier canvas or linen. After years of working in traditional formats, I tend now to use squarer or skinnier canvases, but that can also become an affectation. My career has shown that I can be more contrary than the acquiescing Englishman I imagine myself to be. From art school on, I frustrated people—teachers, dealers, collectors, with my dislike for repetition. I don’t have a huge range of subject matter, but I tend to work in cycles, returning to motifs when I feel my style has changed enough to say something new. I am still faced with a stylistic quandary—in painting established landscape motifs (the coast of Maine, a mountain scene, etc) I tend towards very painterly expressionism. But this approach does not suit many of the less familiar subjects I record around the South. They require more detail. It means I have two, distinct styles. All your readers will know how having different approaches confuses and vexes the art market.

Laundromat (Study) Oil on canvas 14×16

An English painter once told me ‘It’s not what you paint, it’s how you paint.” I get what he was saying, but it is a very European comment, based on the fact that pretty much everything over there has been painted to death! Of course, under those circumstances you would lean towards style and away from a quieter recording of the motif to express yourself. But the statement would be confusing to a couple of dogged realists like Eakins or Homer. My own thought has always been that subject matter defines approach. I do spend a lot of time thinking about what to paint. I feel lucky to be a representational painter, really. It offers me the widest range of subject matter, and a way to process so much of my life.

I am drawing more, and teaching myself watercolor again, having lost most of my ability as a watercolorist through lack of practice. I could blame the market for this—it is harder for galleries to sell works on paper— but that is not an excuse. I now draw solely for the pleasure of it. I regret not maintaining the practice of doing figurative paintings entirely from imagination. This was a strength of mine when I was in art school. It needs to be practiced simultaneously to working from observation, or it withers.

That said, I do feel I paint for myself. My art is a response to my life, rather than a pursuit of sellable subject matter. These days, I am painting some summer mountain scenes, sketching my son, but also a couple of local portraits—a lady who has been an activist for forty years, and a man who was recently exonerated after having spent fourteen years on death row. I plan to paint the State Fair again this year.

State Fair Oil on canvas 30×36

LG: I can see how you would be drawn to Jerome Witkin’s narrative painting with your Ballad series of work. At the end of this interview I’m including a link to your essay, ‘A Southern Edge’ , where you mentioned him while talking about your painting. Can you tell us about what led you to paint your Ballads series? How difficult is it to find the balance between abstract, formal concerns with the need to tell the story clearly?

What makes you sleep so sound? (Darling Corey) Oil on canvas 48×48 2012

Go and do the best you can (Little Maggie) Oil on canvas 60×72 2012

JD: The Ballad series is extremely close to my heart. Just yesterday I sat with two friends, musicians, who will be performing the songs at the museum (Greenville) on Sunday. It was quite moving, and I cannot wait to see the paintings and hear those lyrics at the same time. I grew up listening to such music as a little boy back in London: the old English, Scottish and Irish love songs and murder ballads that found their way, intact, to America. It is my tie to the Southern Appalachians. (I’m one of those painters who needs a human/historical connection to the landscape. American music and literature brought me here)

In answer to your question, yes, I saw Jerome Witkin give a talk last winter here in Asheville. It was great, and inspiring. I was not familiar with his work, but I was delighted at his approach to, and range of, narrative painting.

All my paintings in art school were based on this kind of thing—sea shanties, ballads that explored the passions and follies of us all. I painted the stuff straight out of my head—fishermen getting married in claw foot tubs— all kinds of strange stuff. My teachers thought I was eccentric and contrary. I guess I was, although I felt rather misunderstood!

I’m feeling that way a bit now about ‘Dark Corners’: the Appalachian Ballad’. Obviously, I have a rather evangelical conviction that if I keep on painting this work people will be won over to the poetry of this subject. I see the stories in these old songs as universal, and it fascinates me how I see the exact same emotions and damage every day in the crime reports. However, the response to the show remains tepid so far—not just from the art world but even the world of roots music. Never mind, I will keep painting what drives me.

Regarding the ballad paintings, I’m not sure if I want to tell the story that clearly. They are more about conveying a mood—quite a melancholic one, about being trapped in a place or a relationship. The songs to me are full of a longing for escape, and the often dramatic conclusion, of the murder ballads in particular, is just a way to make that feeling of isolation extremely compelling.

I wanted to set a mood with this body of work, that suggests a story but is not too illustrative. I wanted to play with the scale of the figure in the picture; from tiny to filling the canvas. I tried to play with composition so that the eye sees certain things before others, and I experimented with the background being demanding, invasive, crowding the figure. It’s still a series in progress. My challenge was this—to explore the remaining strengths of painting as a medium to tell a narrative, particularly in the face of cinema.

Where the sun refuse to shine(Dark Hollow) Oil on canvas 40×64 2012

She Looked East, she looked west (Barbara Allen) Oil on canvas 36×38

You guessed about right (Pretty Polly) OIl on canvas 48×72 2012

LG: What 20th/21st century painters excite you the most and why?

JD: I am excited by more recent painting in an odd way, I think. (It goes without saying that the old masters are permanently in my conscience.) I am fuelled by painterly artists like the abstract painters Hodgkin and De Kooning, by disturbing artists like Bacon and Balthus. Certainly I am still energized by varied artists like Beckmann, Bonnard and Matisse. The funny thing is these painters excite me, but do not really move me. It’s hard to imagine such work hanging on my walls. Maybe a small Hodgkin or a little still life by Bonnard? These painters start a conversation for me, they provoke a response, a niggling irritation. Take Morandi, for example. I like the ‘idea’ of Morandi, but a whole book on him drives me nuts! ‘Come on,’ I say, ‘You can’t be doing that again! ‘ But he is much more likely to make me want to paint a still life than a Chardin, who I adore as a painter.

So, for inspiration, I guess I look at artists who make me want to tweak their paintings! That are somehow disquieting. Or paintings that remind me to take a risk or two.

Sunflowers in Paint-covered Pot 6×8

Buildings, Greenville Oil on canvas 20×36

Formally, I have great affection for the realist work of the twenties and thirties, where so many artists incorporated aspects of Post-Impressionism, above all Cezanne, into representational paintings. I love the emphasis of flatness, of paint, of line juxtaposed simultaneously against traditional depth in a painting. I like the work of Antonio Lopez Garcia very much, but most of all because he offers the unlikely hope of being accepted as a realist painter with more than one style of working.

Corner Store Oil on canvas 30×72

LG: In your “A Southern Edge” essay you state: “A part of me has always been drawn to lose myself in paint, to plunge into complete abstraction. I love painters like De Kooning, but I love life’s odd details more.” and in article quotes you as saying … “I try to find something that’s really close to boring, really close to completely nondescript, but something in the composition is endlessly fascinating…”

Many photo-realists such as John Salt, purposely explore banal, snapshot-like subjects perhaps challenging themselves to find subjects with absolutely little visual or human appeal and yet still pull off an interesting painting. Why stop short with something just close to boring and not paint subjects that are actually boring or completely abstract?

JD: Why not paint something actually dull? Or fully abstract? Interesting. I have actually enjoyed trying the former. Euan Uglow-like still lives or a view of the ridge of a hill, or the utter symmetry of a building. I know the painters you mean, and I think it works well, although I would not want to do it exclusively. The fact someone has lovingly painted a nondescript-looking subject does work to make the viewer rethink his or her first impression, to look again, more carefully.

Complete abstraction? I have enjoyed dallying with it once or twice. It suits a painterly need to respond to any very distinct emotion that I find myself visualizing, rather than putting into words. I have a couple of abstract paintings I did that tried to convey something of falling asleep, something of the sensation of waking. You can imagine how successfully these untitled pieces convey this specific experience. I write some poetry, and to me my poem has failed if it is not clear, if has not communicated pretty precisely what I set out to say.

The idea of being pigeonholed by the art world as a painter of pure abstraction gives me the shudders. You abdicate a lot! Unless you’re some heavyweight like Gerhard Richter, you will be expected to stay exclusively to that course.

Clearly, it suits some artists, as writing only ambiguous haikus contents some poets, but not me. I think of the heyday of Abstract expressionism as the triumph of the most unyielding, draconian ‘Academy’ art has ever had. I think it was inevitable that bubble burst. I agree with Francis Bacon that ‘painting is a duality’. It gets all its bones, its meat, from that miraculous journey—from the ‘seen’ world, through the artist’s eye and hand, back to the viewer. But it surprises me how many artists still choose the path of complete aesthetic distillation. I am glad they do, because I enjoy abstract painting very much, but it is not for me.

LG: I suspect that today there are more painters than ever competing in a smaller market than any other time in recent history. Ever year schools release new painters into a world where painters often live longer than ever. At the same time, many galleries have closed or may soon close due to our economic down-times.

Working away from large urban art centers like NYC is especially difficult for painters who step outside the expected, marketable subject matter and stylistic approaches. Many galleries tend to be less willing to take chances on a painter making art for art sake and who might be a difficult sell to clientele less knowledgeable about art.

Paradoxically, the edgy, post-modern art-world galleries often rejects any observation-based painting, in the fear that it is out of fashion. Caught in between the conservative, traditional venues on one hand and hipster galleries it can often be difficult for serious modern representational painters to show their work.

—Is it possible to give advice or encouragement to artist faced with such a depressing scenario?

JD: I will try to answer that based on my, clearly regional, experience. I think representational painters have their work cut out for them. I think artists and galleries got lazy during the boom. Everyone was buying: good art, bad art, whatever, and painters didn’t have to make really strong paintings, gallerists didn’t have to work that hard to make a sale.

We all stopped educating the public. When I first arrived in the South, there were very few galleries. Art was bought by decorators and by the most affluent. Through the nineties, more and more galleries were opening, more and more people were painting, the middle class was suddenly buying art. Statistically, it was inevitable that there would be, alongside the increase in buying bad art, an increase in buying good art. I think we all failed to capitalize on the latter—the potential for the best art to be promoted, for the public to be educated to the peaks of what was going on.

There was a chance for the art world to make a kind of leap, as happened historically when there was great wealth in a society. Instead, the art world in the last two decades just seemed to inflate. We now have a glut of artists. It was a coup for the amateur painter, and for the amateur with an income independent of painting, a chance to get established. Those artists are thriving today—able to keep painting, keeping galleries afloat, while professional, career painters are barely able to keep going. “Rowing under water” is how a fellow artist describes his condition.

Let me make a correction, Larry. I just said ‘there was the chance for the art world to make a kind of leap’. On reflection, affluence is only part of the equation. It helps, but you need a Florence, or a Venice, or an Amsterdam. You need a fiercely driven, competitive elitism, not the democratic tower of Babel the art world is today.

When I ask what is selling (painting-wise) this summer, I am told abstraction and plein air painting. I hear that very conservative, traditional oil paintings are also selling, also some photorealism.

Abstraction makes sense—Corporate offices and decorators love it. Painstaking, traditional oil paintings? I am glad our craft is being maintained in that way, and there are some very fine painters in there, but I’m afraid it doesn’t help educate the public to the nuances of painterly painting (like photorealism, it appeals to the ‘bells and whistles’ crowd who marvel at technique). It works against the kind of intellectual inquiry into painting that is the corner stone of your web site.

Stonington, after Rain, Oil on canvas 18×20 2001

If I can, I’d like to describe the process of a painting of mine that I have here on my kitchen wall—a view of Stonington, Maine, from the window of the apartment I had rented for the month. It might help to explain to those readers of yours who aren’t artists what on earth I’m talking about!

Maine is where I seem to experiment most—no doubt because of its strong Modernist tradition. This painting works on several levels. It seeks to describe the mood of this coastal town in the evening—the light, actually, as the rain clears. On a secondary level, it explores paint. Not just the ‘seen brushstroke’ that goes back to Titian and, my all time favorite, Velasquez, but also the ‘flat-depth’ that Cezanne gave us all to play with. The view recedes towards the distant island, but at the same time is constantly pulled back up into a flat, abstract design. There’s some Bonnard in there—the way I choose to have certain things pop rather than others, there’s some Matisse—in the way certain flat passages are painted again and again, beside others that felt right from the thinnest wash. There are unfinished, almost clumsy patches that give the viewer something to resolve, then moments of detail to reward them. One window on that mansard roof doesn’t match its companion. That’s deliberate. The result is a painting that intrigues my visitors. They look at it for much longer than they would give the actual, real world view from that window. In trying to put together this puzzle of their different aesthetic experiences, the painting affords them time for my art to share a place and a part of my life with them.

Washerteria, Oil on canvas 20×36

As for the popularity of plein air painting this summer? I think there’s also a glut of that these days. It is ‘painterly’ for sure, but again, I feel it has become a bag of tricks that asks little of the viewer. I have friends here, up in New England, in Australia, back in Blighty, who are the real deal. They’re none too pleased at the sudden epidemic of ‘Paint Out’s and the like. Seeing a minor Impressionist out painting a coastal scene, Degas once snarled, “Painting is not a sport.” I quite agree. My kind of painting is about breaking rules (preferably one’s own), not coming up with a list of them and starting a stopwatch.

At this point, I have to laugh at my rather declarative style of writing about art. I have made it clear enough that I can’t abide clubs or cliques or manifestos (have you ever read any of that nonsense by the Futurists of the Surrealists, or the grandiose claims of Abstract Expressionism? Hilarious.) The funny thing is it sounds like I am writing my own, furious manifesto against all manifestos.

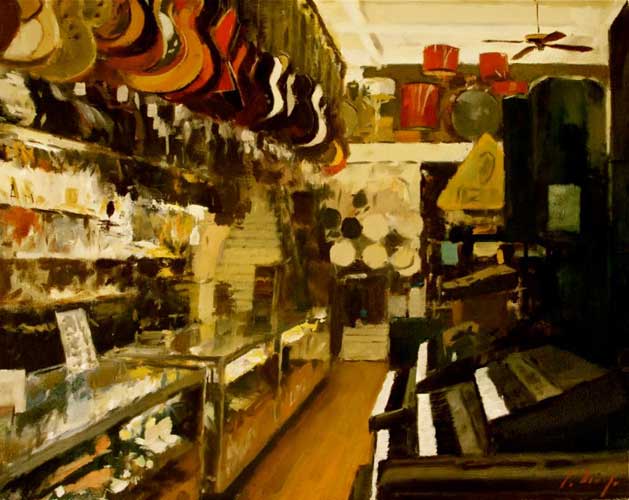

Pawn Shop, Charleston Oil on canvas 16×20

What advice or encouragement can I give to young artists facing today’s difficult scenario? Well, I used to say ‘Find something you would like to paint that the public will want to buy. This will support you painting whatever else you want.’ I’m not sure that flies anymore.

I would suggest finding like-minded peers for support. To try and find your own voice, your most personal voice. This is no time for representing oneself with ho hum studies, or unexciting pictures. When sales are so few and far between, every painting counts. (That’s actually where this recession may prove to be an improving force on us all).

I think there’s a lot of sense in artists forming groups regionally, or by stylistic preference. It lends itself better to educating the public. We all need to be educating the public like crazy! In the Dark Ages, people were as likely to follow animal tracks as use the empty roman roads. The history of art is similarly full of amazing acts of forgetting, of losing mastery. Twentieth Century art was often disdainful of public interest. We cannot expect the public to wade through so much art today, in so many forms, and arrive at our work with complete understanding. Education is essential. Linked to that is teaching. Although I have never held an educational post, and have taught less than a dozen times, I certainly recognize the benefits of a young artist seeking this supplementary income!

I had the perfect example of going that extra mile—to inform the public—just yesterday.

Earlier, I wrote about my ‘Dark Corners: The Appalachian Ballad’ show meeting with a lukewarm response. But on Sunday, I gave a talk at the museum, having had that last minute idea to include performances of the songs between my analysis of each painting.

The place was packed and everybody, finally, completely, understood where I was coming from. They connected the poetry of the ballads to the image. Before thinking to add the music, I had made the classic mistake of assuming too much: of thinking my audience was already informed somehow of my journey. Not having those songs, would have been like starting ‘Moby Dick’ with ‘we could all see Ahab was done for now, but we didn’t expect that crazy whale to turn on the ship.’

So yes, I think education is key, and I think, in all the confusion and panic of the art market, we should not wait for someone else to speak on our behalf. To a young artist, I would say, paint honestly, find kindred spirits, and explain yourself, your art. I think this site, Larry, is a real contribution to taking that way forward. Thank you for letting me tell something of my story.

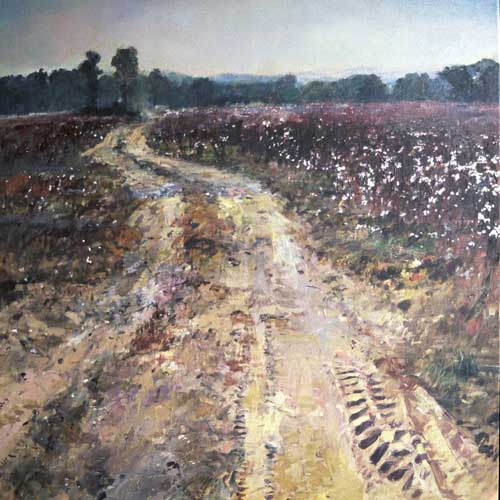

Cotton Field, Oil on canvas 36×36

Here is a link to a pdf essay “A Southern Edge” written by Julyan Davis February 2012

(from Julyan Davis’ website: Julyan Davis is an English-born artist who now lives in the United States. He received his art training at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London. In 1988, having completed his B.A. in painting and printmaking, he traveled to the South on a painting trip that was also fueled by an interest in the history of Demopolis, Alabama and its settling by Bonapartist exiles. Julyan’s home is now in Asheville’s Montford district. His work is exhibited from New York to Europe and is in many public and private collections. Recent acquisitions include the Gibbes Museum in Charleston, the Greenville County Museum of Art (South Carolina), the Morris Museum (Augusta, GA) and the North Carolina Governor’s Mansion and Western Residence. His newest work, interpreting traditional American ballads through the contemporary South, will be featured in a solo show at the Greenville Museum of Art in 2012.

Very nice to see Julyan’s work here. I saw his show a few months ago in Charleston and was impressed by his interiors…the density of the space, the colors and the paint handling. The newer, narrative work I find very intriguing, and I’m drawn to his images of worn-down, rusting places of the South seen by a non-Southerner. Thanks for the interview Larry, and thanks for the paintings Julyan…I hope to meet you sometime in the future either in Charleston or Asheville.

So much of this interview echoes my own thoughts, issues, pleasures, and concerns in painting. Most of all, I thought, perhaps I was the only one ever asked to remove the “ugly” telephone poles from paintings, cheers Julyan. Thanks Larry for another fine interview.

There are unfinished, almost clumsy patches that give the viewer something to resolve,

Very important.

then moments of detail to reward them

Exactly

Enjoyed the interview! Thank you

To Julyan Davis,

Thank you for your clear writing and passion about your work. Your work sings just as the music you relate to. It is inspiration to meet in images and print an artist who takes his work so seriously and personally, and doesn’t apologize for it,

staying on that internal journey that leads to great art. Thank you.

Thank you, Larry, for another significant introduction.

valerie

Wonderful work! I loved the subjects, his perspective on them, and the lush painting technique. Looking for the “real” is such a complex mix of intuition, observation, and seeing the deeper abstractions….and such a revelation when the artist gets the right balance. Thank you.

Great interview and fantastic work. I love Julyan Davis’ outlook as it reflects my mindset about painting in so many ways. That he looks at Beckmann and reminds me of Andrew Wyeth is wonderful.

The idea of not being tied to a single dogma and yet to be so grounded in realism is refreshing.

I agree with Teri’ comment about the mix of intuition, observation and abstraction as they come together to make some very informed paintings.

The interiors are particularly riveting.

Thanks so much for your kind comments. Being interviewed by Larry was entertaining and thought-provoking. I was asked last year to be the juror and speaker for a plein air painting competition taking place next week, and this interview helped me gather my thoughts. Degas’ quote ‘Painting is not a sport’ is all over the internet as the title I gave for my lecture at that event. Interesting.

Wonderful interview; marvelous work!

Congratulations Julyan

wow!! phenomenal paintings! thanks, Larry!

Really nice paintings. I’ve done some paintings inside abandoned houses…he has done some gorgeous

ones! I like how he is trying to put the figure into some of those kind

Of settings…. still think the beautiful light in the empty rooms have the most impact.

I get to see some great work by artists I was not familiar with before when look at the site. Thanks Larry.

I am a Russian artist Vladimir Kochetkov, college-educated, trained realism. 4 years teaching realism. interesting to see how to develop realism in America or Europe. is not the case in Russia.

Julian seems to cast a warm light on what we’d normally view as mundane or depressing interiors. He adds a romanticism to abandoned thoughts. He also makes me laugh quite hard…as he references his “furious manifesto against all manifestos”. His work, passion and education of thought and history of art continues to intrigue me.

What beautiful paintings, and I agree, a realist should be thinking about subject matter — why pretend you don’t care? Also he sounds like a great guy as well as smart and articulate.

Hello Julyan,

I recall meeting you at Highlands some years back. Your recent work is wonderful, very strong images beautifully painted. The interview thoughtful and inspiring and touching on good, tough issues.