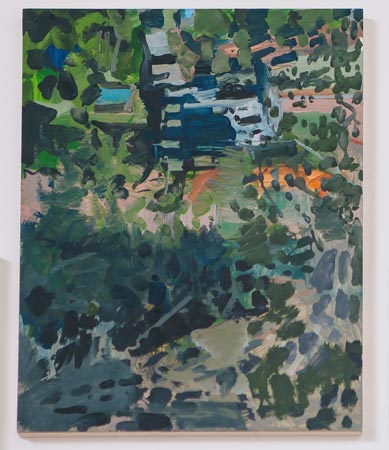

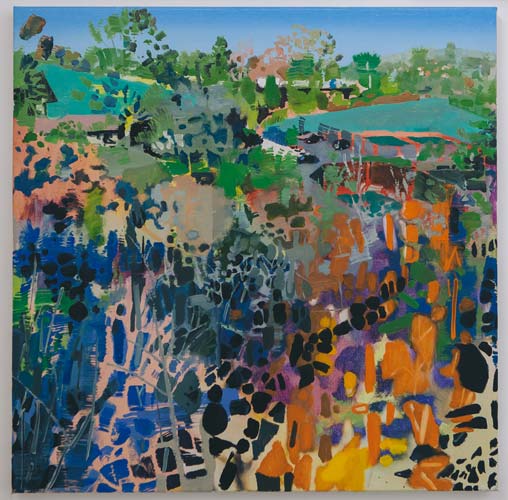

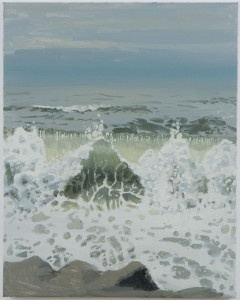

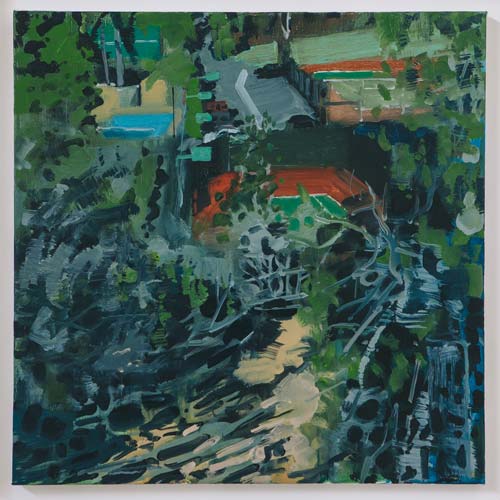

In February 2015 I had the pleasure to sit down and talk at length with the painter Julian Kreimer while he was the artist in month long residence at the Lux Institute here in San Diego. He took time out from his busy painting schedule of making one painting each day, many works done from observation of the surrounding coastal chaparral and nearby structures as well as painting abstractions. I am very grateful for Julian’s generosity with his time in talking with me about his process and thoughts on painting.

Julian Kreimer is an assistant professor of painting and theory at SUNY Purchase College in New York and is a frequent contributor to Art in America. Kreimer had reviews of his show at the Lux in Hyperallergic, Art Critical, and Two Coats of Paint

His artwork has been exhibited in multiple shows around New York City, as well as in Charlottesville, Virginia, London, Washington, D.C., Providence, Santa Barbara, Boston, Philadelphia, and Newark.

You can read more about Julian Kreimer’s residency from the Lux Institute page at this link

Larry Groff: How did you get into painting from observation?

Julian Kreimer: There was a Lennart Anderson painting of a pie tin. Pie dish. That was at the old Knoedler Gallery before they went under. I remember seeing that. I drove down from Providence to see a few shows in New York in grad school and I remember just that one pie dish painting. I had been doing big, semi-abstract paintings that got me into grad school and then 9-11 was at the start of grad school and after a few months none of that made sense anymore. I slowly went back to observational painting. I think that Lennart Anderson pie dish really had something to do with it because it was so convincing as a declaration of what observational painting could be. It such a meaningful, such a powerful experience just to stand there looking at that painting.

LG: When you were in graduate school was observational painting encouraged, discouraged or neutral about it …

JK: It was interesting. It was a weird thing. I got in making this kind of work that came out of the 90s even though I started in 2001. My first day of grad school was September 11, 2001. That was literally the first meeting we had was right after the towers came down. The meeting became about that. I spent the first semester making those big, ironic Kippenberger-type paintings.

LG: I’m not familiar with Kippenberger …

JK: He [Martin Kippenberger] was from Germany, Cologne or something, he comes out the Sigmar Polke tradition. He was a very good draftsman and he would use that facility and make these paintings with slap-dash decorative backgrounds and then he would paint over them with some sort of photo-projected image. He was also a drunk and he died of liver failure in his 40s. I had first hated his work and, of course, as these things happen, became obsessed with it and I started working with that.

At the end of the my first semester, the night before the crit, I put up all these big door-sized paintings that I had made in my first semester and once I put them up I felt there was no air in the room. That was not a good thing. I think I hit that kind of wall. I started the crit by saying, “I put these works up, when I made them I believed in them. Now I realize they’re dead and I need your help to figure out what’s wrong and how I can move forward.” Basically they said, “You’re right, they are dead. They’re not alive and we don’t know how to … It’s for you to figure out how to move forward.”

So right on schedule, I had the typical grad school crisis and I watched My Dinner with Andre and then I re-watched it. I think I watched it three or four times. It made so much sense to me that you could make a film about something so mundane as a dinner, but it was also transformative.

That movie opened me up and allowed me to go back to observation. I had started doing observational stuff in high school and in college when I had the possibility of doing plein air I was doing almost entirely that and nobody told me that you couldn’t do that … It wasn’t an art school. I think if it had been a BFA program I might have had more resistance but when I got to grad school and I started … the thing was it had been awhile since I had done observational painting.

I started with these little pencil drawings that I would work on for a few days and I started looking at Rackstraw Downes and I think I saw Lennart Anderson’s show then. I think I went back to Antonio López Garcia with that movie, Dream of Light. A lot of it became about seeing and that sort of Cezanne triangulation of where things can be translated from 3D to 2D.

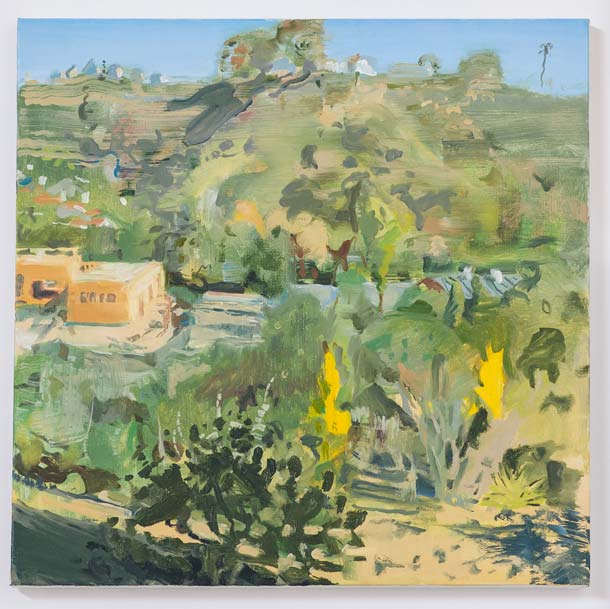

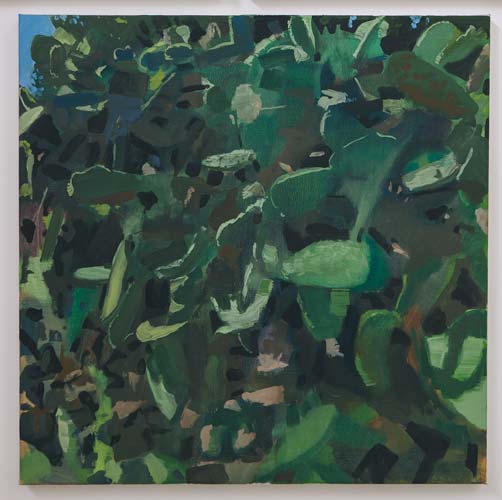

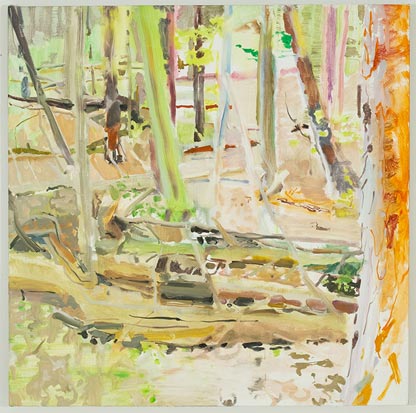

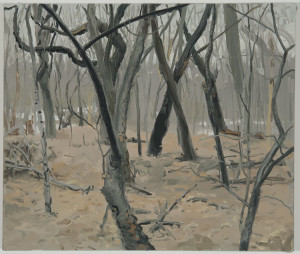

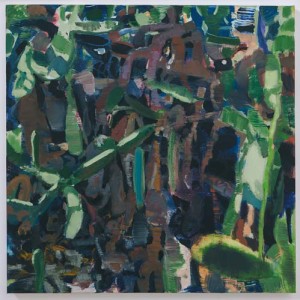

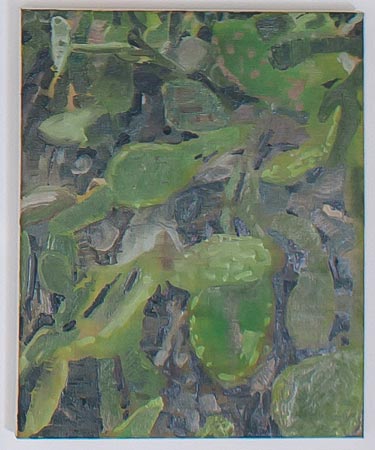

Those drawings took awhile and at the end of that first year, I started going out and painting again but in the overgrown, weed-filled backyard of my rental house in Providence. Actually it was funny because I kind of go back to the same motif every time. It’s basically a painting of my car seen through the weeds in the backyard. I had one of those four door hatchback Honda Civics, the ‘86, which I loved. It was a portrait of the car but also of the foreground given as much importance as the car. Not all the paintings, but I’ve been making versions of that painting ever since.

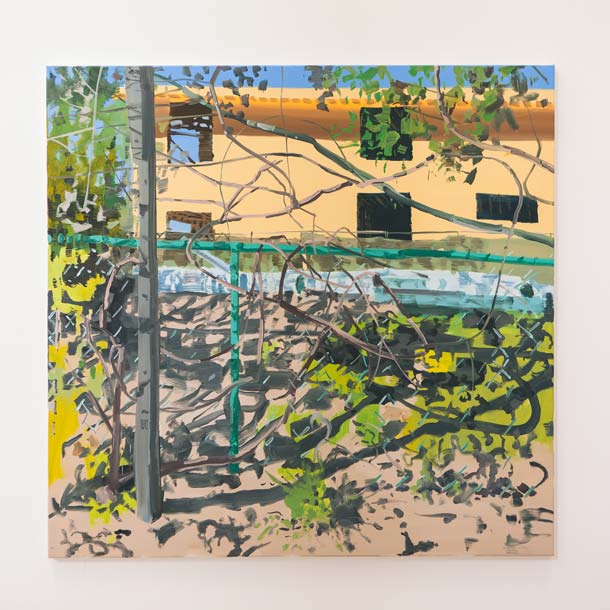

LG: The painting where you have the chain link fences and other dominant structures that somehow are blocking or obscuring your view in some manner? Where you have to look through or past it in some way.

JK: Well, we learn to ignore them. Or we look for the vista, the view.

They’re always there, we just learn to ignore them so the paintings are just giving kind of … I don’t know if it’s the right word, but a more accurate percentage of our view that’s actually taken up by those things we learn to ignore. A lot of them, it’s about this weird way of addressing this injustice of the foreground that we ignore what’s right around us.

This a very long winded way of getting back to your question which was how were those paintings received. When I made that first car painting with the overgrown backyard, that was sort of the breakthrough. It was a black and white painting because I was still learning how to paint this way and I thought I would work on that very methodical Lopez Garcia way so I just took the black and white because I thought wow, it’s going to take me months to be able to do this in color, so I’ll start with black and white, keep the variables limited.

That painting was like the first painting I made in years that was really alive. Everyone could see it. Everyone was excited about that one painting. I was very excited about that painting. That kind of opened it up and in a way that painting was sort of the first real painting that I made, that I’ve been kind of working off that first leap ever since, at least with the observational stuff.

LG: You’re one of the few people who paint both abstractly and representationally. I was looking at your work, and I noticed that there’s a lot of similarities in your approach. That they’re not that divergent. You’re really in a way almost doing the same things except in different subject matter. It’s not really that the process is so … I don’t see it so much as observational painting versus painting from memory or abstraction or total invention. It’s kind of the same thing or would you disagree? Talk to me how they differ for you.

JK: There’s definitely a border there and I don’t cross it yet. I might. I keep getting feedback from people who ask, “Oh, are they headed towards some kind of merging?” There seems to be a kind of enthusiasm towards them merging, and they get closer and then they come apart, but you’re absolutely right. Some of the things are really central to both. The negative space is probably the main link in both: if there’s a kind of formal structure that has heavy symbolic meaning, it’s the way that the foreground that we tend to ignore becomes present in the paintings.

It’s all about negatives. I would say two-thirds of my work is negative space to one-third positive. The figure-ground, not just reversals, but in both bodies of work, I really like when the figure and ground are sort of switching off. Sometimes I can think of an Alex Katz painting or Bonnard, where the figure really becomes almost like the background. I’m really interested in them … The painting’s always moving back and forth with that.

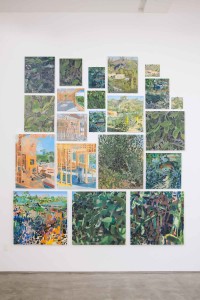

When I do these residencies, I really try to use them as a nice opportunity to paint observationally. I pretty much just do that, because it’s so much harder logistically to do observational painting in my regular life. It’s funny, because I’ve been painting so intensely here and now I feel really excited to go back to the studio. To not necessarily paint from the paintings I did here, but just with all the visual stimuli I had here, I’m super fired up to go back and just make some big abstract paintings that I have all ready in mind some starts for jumping off of this point.

The main difference for me is the abstract paintings I allow myself to paint over and over and change entirely. With observational paintings, I give myself this rule, not always and it’s not super strict, but 99% of the time, I start and finish them in the same day. They’re alla prima, one-shot paintings. Even the big one in the show was a one day, it was the biggest one day painting I’ve done since college.

LG: These are all oil paintings? Are some acrylic?

JK: No, it’s all oil.

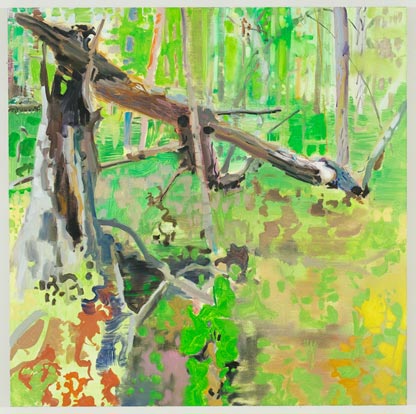

LG: Some of them it seemed like you had painted like a ground like a bright really saturated green and you’re painting on top of it, but it didn’t seem like it was wet into wet, it seemed like it was more … What do you use? A dryer or something?

JK: No, no, I keep it super simple. I’ve figured out how to use those thin greens or the bright colors and sometimes I’ll do certain things like I’ll bring a squeegee and I’ll squeegee it off so it’s still there, but it doesn’t get sucked into the next layer. Early on in grad school, when I started painting observationally again, I developed a reliance on very soft brushes to be able to avoid pulling up the previous layer. I use hog bristle for the earlier layers, but as the painting progresses, I’ll go to softer and softer bristles, so I will literally go from hogs to horses to sables over the course of the day.

LG: You seem to use fairly large brushes.

JK: Yeah, I use a whole range. I mean the other thing about the residency that’s easier here than in New York is that I can bring more stuff out. I can come back and get more stuff so I can bring a couple boxes full of brushes of different sizes. I’m trying to increase … I used to use all the big brushes and the wide range of brushes in the studio, but then for outdoor painting have a more limited set of brushes, and I’ve tried really consciously in the last couple years to use the residencies as a kind of time to experiment, because in a residency you can treat the grounds as your studio in a way that you just can’t elsewhere.

If I leave my stuff out no one’s going to take it here. Not that I have, but I did that at Yaddo. I would leave the tables and the easels out and I could leave some stuff out and it would be there the next day and fine. That allowed me a kind of flexibility. Also, just a lot of it is silly practical stuff. If I’m at a residency, I can use huge brushes and then take an hour to wash my brushes at the end of the day, because I’m a little obsessive about washing them everyday and getting them super clean, for the next day’s work.

LG: Yeah, sure.

JK: The colors, you know, makes a huge difference in the color. I can do that.

LG: Yeah, it’s the little thing in Southern California, we’re all nervous about the drought and wasting water. I have this issue where I like to wash my brushes every day too, but it uses just an insane amount of water that it makes me think I’m wasting and where is all this toxic paint going? The whole thing that you don’t often want to think about as a painter, but …

JK: I don’t really use much water, because I have another method. I did this painting trip in China where I was backpacking and painting oils and staying in little guest houses through the west of China. Often there would be almost no water so I developed some tricks of how to wash brushes with very little water. It’s actually a very … I basically …

LG: Use a lot of solvents?

JK: Yeah, first get most of it out with rags and solvents, I reuse both forever, and then I’ll just pour a quart of warm water into a container and then a few tablespoons of Murphy’s Oil Soap or something. I can go through like a whole day’s of brushes unless I’m using huge brushes, but for a regular day of brushes I can go through … It will take me two quarts of water to wash the set.

LG: Wow, I’ll have to try that. I just do it running under the sink. I hadn’t really thought about it that methodically. Good to know.

JK: Yeah, I have a whole ritual. At home I use Gamsol because I have a studiomate and I don’t want to make it smelly for her. Here, to clean the brushes, I just use hardware-store paint thinner which works really well. It’s super strong and I can do it out in the back so the fumes aren’t so bad. It gets most of the paint off and then the Murphy’s is really just to get the final bits.

LG: Ever try … Lately actually I’ve been trying what someone recommend is just to put it all in a bunch of oil, vegetable oil. I usually use walnut oil.

JK: I tried that for awhile, yeah.

LG: It works for me.

JK: I usually make my paintings in one day, I’m so used to my little method.

LG: There’s no right way. It’s the way that you work with, and I’m not 100% happy with it, but I like it because I work more …

JK: Don’t your brushes get colors carrying over from the last use?

LG: They do. They do a little bit.

JK: That’s my big problem.

LG: It doesn’t bother me quite as much because I work through the grays in my color mixing, so I’m often always putting in a little over almost every color on the palette anyway I mix to adjust the saturation and hue. If I need a pure color I’ll use a new, clean brush. I think your colors tend to be more saturated.

JK: Yes, I use the oil like water color.

LG: Right, so it’s a different way of working. You would likely need to have very clean brushes with that.

JK: I need to start from fresh brushes. For me, a lot of the painting is just learning logistics … I guess the chefs call it mise-en-place, like having your certain sequence of colors on the palette, I know where stuff is, I know the brushes are going to be clean. If I need that hit of pure orange, I’ll just grab it. I always bring extra brushes, I’ll know there’ll be a clean brush, and I bring extra palettes so I can mix a really fresh cadmium orange or something, and sometimes it will just be like one dab on the wet on wet. I need to mix a bunch, a little bit more than I need, get it really loaded, and just pop it in and that will be a one-use brush that day.

LG: There you go. Having lots of brushes helps. It’s a drag to wash them at the end, but it’s nice having them when you need them.

JK: That’s what’s nice about the residency … I don’t have to rush to pick up my daughter. If I’m in the studio, let’s say I paint till … Sundown here as been around 4:30 or 5, so let’s say I’m painting till 5, I get back around 5:15 into the studio, I can wash brushes till 6 and clean the palettes off because that’s another part of it, and I don’t have to rush off anywhere. In New York, it’s often not the sun that’s determining the length of the painting it’s the brush cleaning plus the commute to where I’m painting plus getting changed and all that.

LG: Well, once you get further along in your career and you’ll have assistants to wash them for you.

JK: The funny thing is when I did the big painting, I thought there’s no way I’m going to be able to do this in one day myself and I really wanted to try to tackle it in one day. There’s a really nice guy who’s working at Rhino, the art supply story, a guy named Brian Weisz, if you give him a little shout out. He was great. I hired him and I thought I’m going to splurge. I’m going to get the assistant for one day, because I got this huge canvas and I really want to go all out. We went for it and had been working since early morning and at the end of the day he was clearly beat, and so I said I guess it’s not worth $15 to pay you to wash the brushes, so even though I had the assistant for the day, I still ended up washing the brushes myself and I thought, “No, I don’t think I’m ever going to be able to …” It’s going to have to be a whole other level. That would be really nice if somebody washed the brushes.

LG: I’m sure it’ll happen. To back track, when you were talking about the negative spaces in your painting and the similarities between the abstract and the observational, that was the one thing I was thinking about when I was looking at your work is that not only did the subject matter and especially in many of your earlier paintings that I saw on your website where you’re looking through the chain link fence or some other like parking lot structure or something, you’re sort of looking, it’s not just the subject, it’s also the paint. You’ll have like a flat area of a lighter color and then you’re sort of looking through these overlaid darker colors or shades and sort of looking through the various layers in the same what they you’re looking through the subject matter and I found that really interesting. Then obviously, in your abstract paintings a similar thing going on.

Now, it didn’t seem like you were using any kind of mask. I don’t know if you were masking off the shapes or it’s just the way that you painted. I know you say you use the squeegee.

JK: Yeah, a lot of the harder lines are squeegees.

LG: I just find that very intriguing and this dynamic very curious, and I wasn’t … I couldn’t really think of anyone that had done quite like that.

JK: There was a Lois Dodd painting. There are a few of hers where she was looking through … She’s been a huge influence.

LG: That’s interesting, I just had an interview with her a couple days ago.[link to the interview with Lois Dodd]

JK: You’re kidding.

LG: Had a long conversation.

JK: On the phone?

LG: On the phone, yeah.

JK: Oh, wow, yeah, she has a show opening next week.

LG: Yeah, I’m hoping to have it all finished for her show at the Alexandre.

JK: That’s great…She’s fantastic. I mean she’s such a good painter. She’s like a zen master.

LG: You wrote an article about her for Art in America.

JK: I had done a feature on her. It was more of like a celebration of Lois Dodd. I felt like here I was a younger painter. I mean I’m a better painter now then I was then, but I felt it was important for a younger generation to discover her. She’s turned out to be such a huge influence on younger painters in the last 10 years.

I can think of any number of people who go for her directness, her freshness, the sort of no nonsense… the lack of bullshit in her paintings, but not in an aggressive way and sort of how hard it is to be that simple. I think that’s something I see sought out in a lot of paintings today. Some obvious examples are Josephine Halvorson and obviously me. Different career levels, but there’s a lot of younger painters who are really looking at her.

There was a painting of hers, and I had actually been thinking about this for a long time, of where you see right through a house. I always liked that experience of walking by old clapboard houses. This is something that would happen in DC when I was growing up, where you walk by a house and there was that weird moment where it’s stucco or something and then clapboard and then you look and there’s that green that in DC is so intense and you see that backyard green zoom right through the dark inside of the house. Even before I knew Lois Dodd’s work, I actually tried to make a big Alex Katz rip-off painting when I was studying in London for a year of that experience, with the white foreground, the black window and that burst of bright green popping through that.

Then I discovered Lois’ work and I realized that was a motif she had done a lot of, these flat planes where each of them describes a different set of yardage and space. The issue of space became central. It’s central to my work, of things that are close and things that are far and pushing and pulling them back and forth … I could spin out all kinds of symbolic things about what do we think is important? Shifting the emphasis on things that we want to see versus things we chose not to see, but it’s a very simple, it’s almost in a way a very simple idea and yeah, I think that drives both the abstractions and the observational paintings.

But they’re separate bodies of work, because they have a different sent of rules. The abstractions don’t come from a specific compositional idea. Maybe the rule is that they come out of free play or often, they’ll start with the worst possible composition I can make just so I have something to play off of. The observational paintings almost always I have to find a motif I find intriguing to start.

LG: Do you make thumbnail studies or drawings or view finder?

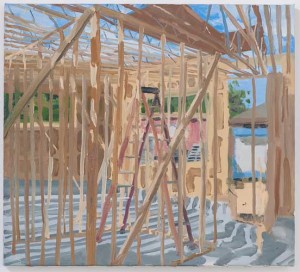

JK: Yes. I’ll make these little thumbnails. These are for the tennis court paintings. This one was of the construction down the hill. Usually they’re pretty abstract. I mean they’re in a notation that I understand and what makes sense for me.

LG: These drawings are a more linear type of thumbnails.

JK: Yes, there’s a lot of negative space. I got one of these brush pens When I started I was using the thinner pen and that was fine, but then I got one of these brush pens and I started using that. Then I could do more of the value stuff with the negative space just like a little sketch or something.

I’ll do the thumbnails and then here I’ve had the luxury where I could do little oil sketches on boards, which I normally don’t get to do. In New York it’s so hard to find places to paint where the conditions are all right. I’ll spend a few days just going around on a bike or walking or driving or subway, whatever, and just scout out spots. This summer I spent probably three solid weeks scouting out spots, and found about two. It was terrible. It was really just swinging and missing. In New York if I find a good spot, I’m just going to go bring a good canvas the next time and go for it and hope for the best, because a month later that site will be destroyed or it’s going have some disaster. I’ve learned to move fast in New York. Here at Lux, I could take a day and do a small painting or a little sketch which is really ideal, because then it really helps figure out the color and the composition and I can sort of figure out the details.

Also, working from observation, a lot of it has to do with the site you’re working on. Not just what you’re looking at, but where you are, because you have to think about if you’re going to get baked by the sun? Are there thorny bushes that are going to get all over you? In the city you worry if you’re in the line of traffic? Are you in a place where people are going to really bother you? I don’t mind that a little bit, but it’s easy to get too much.

LG: Cityscapes can definitely become more problematic logistically.

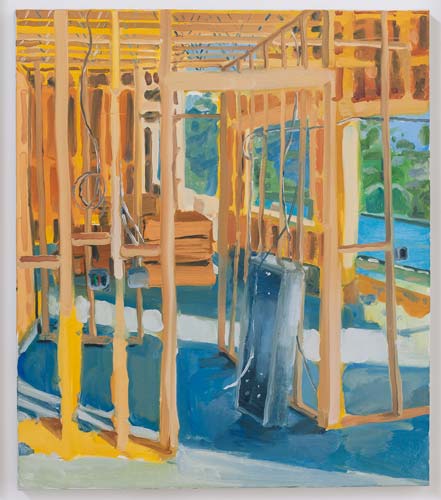

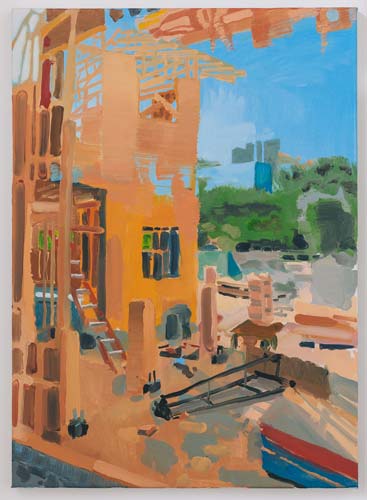

JK: Well, the city, it’s almost … Some of the paintings I did here have the intensity of the city ones. The first three I did in the construction site have it, because I snuck in and I really didn’t know if it would be okay. I was really very nervous about getting busted and I’ve done paintings that are sort of borderline, are illegal before. In the city you’ve got to really … It’s partly you go, you do it as fast as you can and you get out, because the longer you take, the higher the chances that it’s all going to get messed up through something because the factors are so many.

It’s harder to make this work in the city, because I have to think about my lunch. I have to get that ready. I can’t step away from the painting to go get food and just getting there is a whole issue. If I bike an hour and I’m lugging this gear, it’s going to be exhausting.

LG: Is the light much of a factor for you? I mean do you limit to like a certain window of time where the light is the way you want?

JK: I favor afternoon light just because by the time you get out there, It’s nice that the light is ideal. If it’s good in the morning, I’ll figure out a way to do it. It might mean that I get everything set up … I don’t know. Sometimes I would start … I guess I really don’t start the night before. I read in Rackstraw Downes’ diaries that he leaves at five in the morning or whatever to get that morning thing, but with a kid and everything, it doesn’t really work out that way for me. I would say the only painting that I do in a morning light, I do at residencies, because the practical issues are so overwhelming.

I do a lot of the sketching and a lot of the scouting of spots in the morning. I very much am thinking about where’s the light going to be at 3 o’clock? That’s kind of the sweet spot where the painting’s composition is laid out, I can really push the tonal values back and forth and predict.

LG: The light and the structure of the motif that you’re looking at is really … I get the sense, correct me if I’m wrong, is perhaps more of a taking off point for you, it’s not really about a specific moment of light or a specific thing in the landscape. It’s really more about the painting or would you say that’s not true?

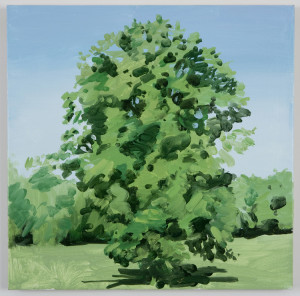

JK: No, that’s not true. I think it’s really that the motif has to click. I made paintings where the motif is so-so and they just end up so-so. I mean I’ve made so-so paintings out of good motifs too, but I really have to find a good motif to work from. Occasionally if I work from a bad motif, it will become a good motif, but almost never. I have to really see a motif with a sociological kind of history of it, who’s looking at this thing that is being painted, where is it? What are all the signifiers? With the paintings here, Southern California landscape, it’s such a known landscape from TV. Even before I’d been here, I knew this landscape in a very deeply superficial way of seeing it my whole lifetime. Three’s Company was in San Diego, right? I think so, somebody told me that.

LG: I never saw it.

JK: Somebody told me the Regal Beagle was in San Diego, but this landscape is so televised. It’s such a big part of the culture I grew up with in the 70s and 80s and 90s. Being here is kind of an amazing thing. It’s like I’m in the set of some movie or TV show that I know from deep memory.

All these concern the issue of cliché. With landscape for me, a big part of it is the issue of cliché and how do I negotiate working this very old-fashioned way.

LG: Speaking of cliché, many observational painters that I’ve talked to, in some way or another have felt that by close looking at nature helps you to sort of dissipate clichés. It’s like what you’re actually looking at it, if you’re really looking; it transcends any of this other stuff. It’s just like you’re finding more formal things out of that particular shape. It’s a very particular shape, a very particular sense of light, and when you really go for it, it frees you up from the obvious solutions. You’re making something that’s uniquely yours. Intense looking can help you tap into something unexpected. Do you find that? Do you think about that?

JK: Yeah, I do, I do. I feel like when I’m painting a lot and charged up and really on fire, like when I’m painting in residencies… I partly set up my making-a-painting-a-day project, because I know it just forces me to go out and paint super intensely and get into really good shape with painting and observing. I always feel like the better I get in a certain set period of time, the better painting shape I’m in, the more clichéd an image I can take on and make it authentic somehow, like what you’re describing. If I’m just kind of coming from drawing or I haven’t been painting observationally for awhile and I tackle something that’s a very known image, it just stays as a cliché. I suddenly noticed in the past 3 or 4 years where a lot of artists have been using the chain link fence which has become such a common motif … I actually did one of them here, but even something that had seemed not like a cliché becomes a cliché.

LG: It seems like everybody’s doing something a little different. I can imagine in a way how Lois Dodd being an influence with your chain link fences, perhaps how you could use the negative shapes inside the links to make up composition, similar to how she uses the window panes as a compositional device. But I don’t know how much you move around your head and everything would change.

JK: Yeah, it doesn’t work quite that way, but the…

LG: Rather than just making marks to represent the idea of a chain link fence, which is more of a cerebral process than a visual process if you get my meaning.

JK: I don’t, because actually it’s funny, I don’t work … I know what you mean in certain ways, but with the fences in particular and with a lot of these, I don’t so much think about sort of the puzzle pieces inside each little square. I really think about it in terms of like almost a printmaker with plates. I think about the space as plates so I really go through the planes, the spatial planes, of what I’m painting. I’ll literally paint from back to front a lot of times, not always, but a lot of times. The farthest thing is the sky. I’ll start with that and just work my way forward to the vine on the fence. The fence will be the penultimate thing and then vine is the last thing.

LG: Is that like a rule for you or is it just what interests you?

JK: It’s not even … I don’t know if it’s even what interests me. I think it’s just the kind of working method I’ve developed. So with a chain link fence, for me the game is that whatever is behind the chain link fence is going to get painted over with this chain link fence, but how do I do it in a way that I preserve that thing behind it and still give the feeling of the fence?

LG: If you got into a situation where …

JK: I don’t do the Lopez Garcia thing where I find where the fence intersects with this little…

LG: Yeah, no, I knew that. I was sort of throwing it out there to talk about.

JK: I’m curious about … I didn’t quite get what you mean about the cerebral vs. the visual difference.

LG: Well, one thing … It’s like you know sort of like here goes, I painted all this background, the various layers and space and here goes the fence. You’re not really looking at the fence, you’re drawing a conception of the fence.

JK: Yes.

LG: You know what I mean? It’s not this one is a little bent more this way than this other little notch, who cares really? It’s like it’s not about that.

JK: It took me a long time to be able to say that, “Who cares?”

LG: Well, anything really. I mean who cares that the branch goes this way or that way? It’s how you do it in the painting, but the fact that you would care is in itself very transformative I think. That no one would care, but the fact that you cared makes it special and it brings you out of yourself to make something different, but not everybody does that. If somebody could do that, it would still suck. It’s not guarantee of anything other than some people do it and they love it and then some others don’t. I don’t mean to imply one way is better than another rather I’m just pointing it the difference.

JK: It’s interesting, because with Lopez Garcia or Euan Uglow, they have such a big influence on a lot of observational painters, and it is that insistence in getting that right and almost like the lineage of Cezanne of these endless series of relationships, these infinite series of relationships and trying to get some sort of handle on that. I think I went through that for a while.

In my second of year grad school, after deciding that I wanted to work observationally, it became a question of how do I do it in color? That became my second year of grad school, was basically learning how to paint observationally in color. I spent three months on these two paintings that were painted every day within a certain hour-long period that the light was just right.

I worked for three months on these two paintings trying to nail everything down and I think once I hit that level of hard edge realism, something between Antonio Lopez and Rackstraw Downes. When I moved to New York I realized there was no way I was going to be able to work this way. I started trying to work that way on the street, and there was no way I was going to be able to go back to the same spot for over three months. Rackstraw manages to do it, and it’s amazing, but I wasn’t able to do it. I realized that I would have to figure out how to paint them in one shot and when I made that realization, it kind of closed off a whole set of doors and opened up a whole set of other doors.

I basically embraced the one day thing and it forced me to do a certain kind of … Have a certain kind of rigor in the painting, but also I became very ruthless. A lot of it is … If I’ve got an hour and a half to nail the light before the sun gets into afternoon mode, it’s really important that I have that gestalt feeling of how do you make the most impact with the least effort. I think of this as making a judo edit – which is what my wife, who is an editor, calls it.

LG: How has being an art writer affected your own work

JK: Yes, my writing has influenced my work a lot. I have the luxury that I generally get to write about stuff I am interested in writing about, so if I see a show … like I just wrote a Stanley Lewis review (for Art in America)

LG: I read that.

JK: … and he’s somebody whose work I’ve been interested in for years. An editor assigned that piece , and I was super-excited to get that assignment because it gave me an excuse to really mull over his work for a few days in a way that I just wouldn’t otherwise. I’d go see the show, and look at the paintings, but something about writing it makes me chew on the work in a different way.

The same afternoon, I went to see the John Walker show uptown, another end of the observational painting spectrum, but equally an observational painter and probably somebody closer to my lineage of observational painting. That one I pitched to them, because I was just so excited about the show and I thought, wow, this is really great work. I can’t really put my finger on why it’s so strong, but it’ll give me an excuse to figure it out in a few hundred words. If I can’t figure it out in the process of writing about it, then forget it. I’ll never figure it out. The writing has been really nice to be able to really …

LG: Have you met him? John Walker?

JK: Yeah, I met him and ended up having a studio visit. I’d visited his studio years earlier and was impressed. I’d known his work before and really loved it. I’d seen his show at the Phillips Collection, and just seen his shows over the years. The studio visit I did was a few years ago, when I was at BU for the day, and then seeing this new show, I sort of expected the work to be like what I saw in the studio but it blew me away that it was totally different. So being able to write is a nice opportunity to really chew on something, it’s a very digestive metaphor.

I like writing about people who make stuff that’s not like what I make. I’ve learned a ton from research for longer pieces, about Lynda Benglis, or the Chilean video artist, Juan Downey, who were so open in their practice. He would do video drawings, performance, architectural stuff. He came out of architecture school, and just had a very open practice, and that gave me a lot. Writing about him and researching his life and his career really opened me up in being able to make observational paintings and abstractions, and stop having anxiety about these two different bodies of work. Yeah, so a lot of them, it’s almost like a great chance to learn.

Occasionally I write about something I don’t like, and that’s also interesting, just to figure out what is it that’s missing here. I always think about it. The negative reviews … I always think about why doesn’t this quite click? It’s almost like a detective thing, finding what’s the missing ingredient for me, and obviously, I’m sure the artists don’t agree with me on that, but it’s like what’s not happening there for me?

LG: I often get the impression that the art world, especially in print magazines, doesn’t pay much attention to painting these days, especially observational painting. I’m sort of curious if you can throw some thoughts out there why that is, or perhaps you think that’s not true and perhaps unfair for me to say that. I’m not sure that you’d consider yourself an “insider” but I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this subject.

JK: I think the art world, there’s so much more stuff that’s made and discussed and so the column inches per medium and per sub-medium within, or per sub-genre within the medium, are just proportionally smaller. When Fairfield Porter was writing, like seventy percent of what you saw in serious galleries, in all galleries, really, was probably painting. Now, within the galleries, let’s say the several thousand galleries that would conceivably get reviewed in print magazines, let’s say, painting probably gets shown forty percent, and so I’m not entirely convinced that the column inches aren’t proportional to just how much is being shown of it in any given moment.

I think observational painting, and this is something that I think we all wrestle with, it labors under a pretty heavy burden, the same way that Vivaldi … having him played in malls around America for decades hasn’t helped him. It’s pretty hard to hear the Four Seasons, and not, for me at least, think of malls. When I heard some performance of it on the radio, and it was truly amazing, I actually could hear the song again, without this kind of overlay of having it … sort of this cheesy overlay, and I think observational painting, because it is default “art” for a lot of people, has to deal with that.

JK: It’s also really hard to write well about observational painting in any interesting way. I always think about how easy is it to write a pretty straightforward press release about some sorts of work. I think observational painting is one of those things that you really have to understand well to be able to make an interesting argument about it.

That’s not necessarily true of appreciating it because I actually think a lot of people like observational painting because they think they get it on some level, but it’s very hard to put that into words. It often quickly gets into philosophy, about who we are and our relationship to the outside world. A lot of it, in my way of thinking about observational painting, goes back to what you were talking about earlier: how do we experience the world differently and similarly to other people and how is one viewpoint speak in a convincing way? I think it’s one of those genres that’s particularly hard to write about in a way that people who aren’t already observational painters would find engaging.

LG: One reason for that, for good observational painting anyway, is about the formal painting issues, visual issues rather than narrative. Issues like socio-political-psycho-sexual or any of those other concerns are far less relevant to what you see in the paint. You would need to to have some background in art history or knowledge of painting to appreciate it fully.

JK: I don’t know if I agree entirely in that I think in a way observational painting for me, the formal issues are the way that you get to all the other stuff. You can’t get to the other stuff, the other stuff is not in the foreground. You have to go through the formal understanding of the work to get to those other things. I think people respond to good observational painting because on some level it’s speaking to those bigger life things.

I think for example all those formal issues are at play in pure abstract painting, but the audience for pure abstract painting, I would guess, is smaller than for observational painting. Not necessarily in the art world, but just in general. I think people respond to observational painting because it speaks to issues beyond the formal, but you have to have the formal there to be able to get to that other stuff.

It’s like hearing one concert pianist play the same song another one played, but you get a whole different set of concerns. It makes you think about childhood and death versus thinking about dreams and materialism or whatever. I think the really good writers that I like about observational painting, and Fairfield does this, can read the formal stuff and then take it to the next level of understanding a larger picture with it.

I feel like sometimes observational painters now, I’ve heard of a few, they’ll do something where the other stuff, the psycho-sexual or the socio-political or whatever is foregrounded in a way that makes it very easy to get to in a press release-able way. I find that disappointing because it seems like a shortcut to me. Like they should get there through the formal stuff that you were describing and have it there as opposed to getting that payoff right up front. Then you get tricked back into enjoying the formal stuff.

LG: What about somebody like Rackstraw Downes? You mentioned him a few times. When I see his work I don’t really think of any narrative other than the visual narrative that he’s set up for him, his process, the whole thing. Now I’m sure people writing about it can think of stuff, but it really I suspect would have no relation whatsoever to what he was thinking about.

JK: I don’t know if that’s true.

LG: I can’t say that for certain but that is the impression I get.

JK: I read some of his books. Yeah, actually it’s funny you mention him because he was one where it really did click for me that you could do these two things at once. He’s so formally strong. There was a painting I saw at a group show at the Yale art gallery and it was also in grad school when I was trying to figure out how to make observational paintings that I could stand behind. He had a really small painting of a suburban New Jersey neighborhood with one of those oil tanks that rise, you know those ones that rise and fall depending on what’s inside?

LG: Sure.

JK: He had really nailed the light. The tank was really low, and he had really nailed the light and shadow on those little lines of metal on the empty armature of the hexagonal structure . To me that painting was so strongly about a kind of way we live in the environment that it seemed like a painting version of … you know the photographer Robert Adams? He’s one of those New Topographers from the ’70s who shot a lot of development in the west. It was this western landscape. I mean this is the same thing I’m really interested in, this western landscape that we sort of know and adore from the 19th century and then the way you have all these ticky-tacky houses everywhere and the inevitable, seemingly unstoppable encroachment of development.

I felt like Rackstraw was doing it, and Adams, they’re beautiful photos but in a way photography has this tendency to foreground the socio-political or whatever. Rackstraw was doing that too. When I see those Rackstraw paintings I think about urban planning, maybe because my mom is an urban planner, but I think a lot about class and the way people live in New York. The way that for example you have tennis courts and tenements right next to each other. What dreams went into thinking about putting those tennis courts there and the layers of urban planning that create these big highways and then what gets torn down? What are the old buildings that get left behind?

For me those Downes paintings are formally amazing, but they’re really, even before I had … I’ve never written anything about him, so I guess without having written about him to me they seem very much to engage with these other external concerns. Then with somebody like Lois Dodd there’s the whole issue of her being a woman and a single mom, I think a lot of the writing about her from the ’70s, like Pat Mainardi who wrote a lot of great stuff about her, and they were strong feminist statements in both the way she was painting, which was very anti-macho, but also the subjects. They were paintings of laundry drying or domestic interiors.

There were paintings of the woods too that had a strong formal… The external stuff was there. It’s less on the surface for me than Rackstraw. The way she paints the nude figure in the landscape with those paintings she does of the woman with her laundry. Observational painting is all about the gaze. She does not sexualize that figure at all. It’s hard for me to think of a male painter who paints the female nude in such a unsexualized manner. It’s a totally different way of looking at the female nude. The gaze becomes very important. Who’s looking? How do they look? Is it different? I feel like I’m a city guy looking at the country out here. That comes through in the gaze. I don’t live in the country so it’s a very different relationship.

Handsome work and a great interview! Loving the construction and chain link fence paintings especially.

Nice interview in that it invited us into the thinking process as well as seeing the final results.

Very impressive both the work & the interview.Thanks. The remark about Vivaldi struck a note, I think that representational,observational painting has long suffered from relative neglect due to its appeal to a less educated group,in

the form of magazine illustration. In short, in colleges across America students were introduced to paintings found in the Museum of Modern Art, etc. So given the power of the press in the form of the Art Magazines, & the upward swelling of money in the Gallery industry & the prestige of Academia we are were we are. This past year at the American Academy in Rome three crows were free to fly around the Library where books on revolutions were placed on tables for the audience to

view. We are fast approaching the 100th anniversary of the Dada movement, nice to see Academia is catching up.

The difference is that Dada was fun and Dada was new but these days there’s not much art that’s new and not much fun either.

Thanks for the engaging interview, discussion of process, and the many reproductions of JK’s paintings. The ‘Construction’ series is especially enjoyable with regard to the idea of seeing through buildings or homes that will soon provide further visual obstructions and views. I like also the effort to develop further the impressionist ‘screen of trees’ motif (Pissarro in Pontoise) with processed timber rather than a mature orchard or forest at the edge of town.

The painting ‘Turquoise Fence’ is absolute painterly inspiration. The hi-key orange-yellow stripe suggesting the under-hang of the building’s roof juxtaposed with the turquoise fence is brilliant, as are the other lower color key relationships in the foreground sand and the upper branches painted in a similar sand color dancing and over the buildings’ facade. The branches echo their grey shadows in the foreground, and the overall exuberance is enhanced with the punch of the yellow on the left…and all in a satisfying tripartite composition. Simply a wonderful painting. And a very enjoyable interview. Thank you.

cactus paintings, wonderful….

Where can I see his work to buy!!! very interested. Great work