Jordan Wolfson, Interior with Two Chairs and Window VII, 2002, oil on canvas, 48″x42″

by Elana Hagler

Long before I had the pleasure to meet him in person, Jordan Wolfson’s name conjured up images of atmospheric, energetic paintings of interiors, objects, figures, and landscapes that seemed to slip in and out of various states of being. Seeing the paintings in person, the images are built up thick with paint resulting in a very active surface, unified by a soft, satiny sheen. Staccato strokes of paint mimic the darting eye and luscious, vibrating patches of color hover somewhere between air you can touch and form you can breathe. Jordan Wolfson’s work embraces life in all its succulence and opposition…grabs it and envelopes it in a warm and very human light.

Elana Hagler: I’m struck by how fluidly you seem to move between observation and abstraction. The sense I get is that your more tightly-expressed work and your more abstract work are polarities of your visual/tactile approach to painting: the tighter work has more to do with vision and the more abstract work slips deeper into the experience of space as explored through touch. Can you tell me something about what you are going for in these different ways of approaching picture-making and about the experience of working in these modalities?

Jordan Wolfson Yes, you have that right, about the interest I have with the twin attitudes of the visual and the tactile and how they align with a more representational or more abstract mode of working. You use the terms in your question – observation and abstraction. A couple of thoughts right off the bat—one, what you’re calling “observation” may traditionally mean what folks usually term representational or realist. And two, I just want to clarify that the work being termed abstract is also done from observation—all the work is done while in an ongoing relationship with the observed motif in front of me. Maybe the way I would describe it is that when I work I’m playing with different parameters, like different rules for different games. There is the tonal game, the touch/tactile game, the space game, or the edge game, for example. Sometimes I’m more focused on investigating and advancing the clarity of the objects, the observed form, and the painting might look more traditionally representational. And sometimes I want to explore the experience of the space more—what’s in between everything. Sometimes I’ll reduce the value range as a way of exploring the sense of projected tactility, like the experience of stepping into a dark room and sensing the form before me.

I guess I enjoy switching it up—like putting music on shuffle—contrasting the touch and attitude keeps them on an edge. Working in different ways keeps my energy fresh and the sense of investigation fresh. Also, I’d like to say, before getting too heady or philosophical about it all, that very basically, I just enjoy working in different ways, and of course, that’s not particularly novel. Look at Picasso, the range that Diebenkorn explored during his lifetime, de Kooning, the difference between Dickenson’s large slow work and his fast smaller premier coups – or the difference between Titian’s pen and ink drawings and his charcoal works, or someone more contemporary like Gerhard Richter. In a way, Titian’s drawings are a good example because they so clearly illustrate using different aspects of a human sensibility. I guess I would say his pen and ink drawings are coming more out of a purely visual attitude—the drawings are not just more linear, but they generally address situations seen at a distance like landscape (one exception that comes to mind is the working drawing for his Saint Sebastian—pretty sculptural). The charcoal drawings are stunningly sculptural and tactile, dealing with mass and physical structure. And we get that so clearly in his painting—the weight, the feel, the touch, the body—flesh! How does it go? Was it de Kooning who said flesh was the reason oil painting was invented?

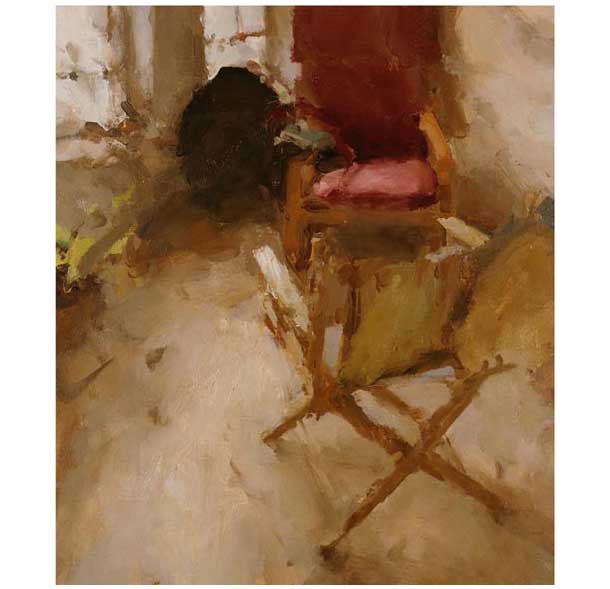

Interior with Director’s Chair II,, 2002, oil on canvas, 53″x40″

Still Life with Rosehips and Turquoise Bowl I,, 2011, oil on linen, 10″x12″

Still Life with Rosehips and Turquoise Bowl II, 2011, oil on linen, 10″x12″

JW: In relation to the bit about switching up my terms of inquiry, my rules of play, the kinds of questions am I asking—questions about form, mass, light or space— there is also the desire to bring as much of myself into the painting as I can, as many parts of myself, different energies, different interests, different velocities. You know, in music there are different speeds, not just in Beethoven—presto, adagio—whatever, but in Neil Young – folky and grungy – so, why not in painting? I’m bringing different parts of myself into active dialogue, not just with the painting, but with the actual physical situation that I’m facing. It’s not just that the motif gives me an excuse to paint in different ways, but that these different ways of painting allow me to inhabit and face this physical situation in different ways: they allow me to experience being in different ways. Andrew Forge writes about just this beautifully in his introduction to a book on Soutine.

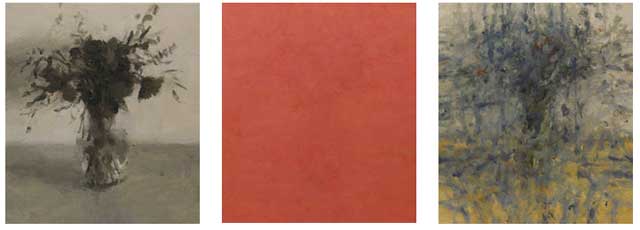

Still Life with Flowers in Three States, 2007, oil on linen, 25″x93″

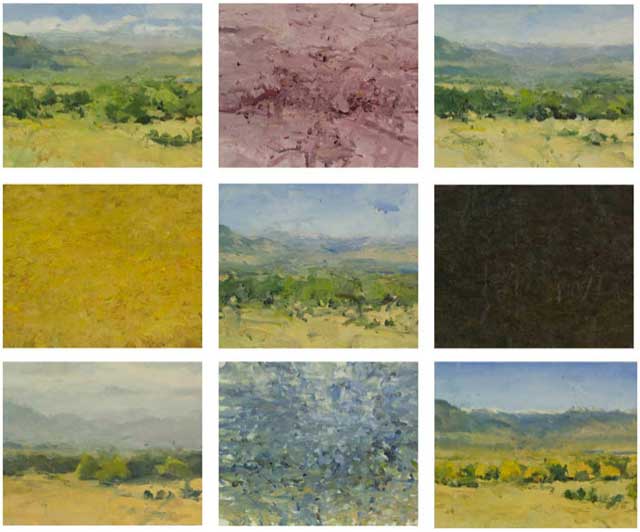

Sky, Mountains, Valley in Nine States, 2010, oil on linen, 54″x66″

EH:

What makes you choose the format of the triptych (or polyptych) for so many of your works?

JW: The diptychs, triptychs and polyptychs allow for the juxtaposition of these different modalities that I mentioned – these different sets of questions or parameters. I find that when I do that, placing paintings or drawings that are stylistically different next to each other, something else becomes available through the way the different images feed off of and differ from each other. This is something essential that isn’t found in form, isn’t visual – and I don’t mean to be cryptic—it’s just the way it is. And I’m interested in that.

This kind of juxtaposition started for me (this time) in 2006. I had put up a show at the DFN gallery in New York – at that time they were in Tribeca—and the way the work functioned in the gallery was, of course, quite different from how I experienced it in my studio. In the gallery space each piece was a picture—one picture, then another, and then another. But in my studio they worked together synergistically, more directly, paintings and drawings, working off each other in a kind of common endeavor of investigation. And I really missed that feeling, that experience, in the gallery. So I thought – well, maybe instead of having a series I’ll just take three or four works and put them together as a polyptych. And as soon as I did that I realized that this was something that I’d done back in my twenties. There was a kind of misreading of Jennifer Bartlett I had that gave me permission to do a still-life of bottles in four different modalities —one had words written on it that were basically illegible, one was very light in its tonality, one kind of exploded and one was muted and very greyed down. And then a couple of years later I did it again with a still-life of dried flowers, this time in Jerusalem, in my late twenties. I had this love for the subtleties of Morandi and Ad Reinhardt and Milton Resnick. And I thought – now going back to 2006—I thought how I missed all of that, and I wanted to do that again. I’d been painting in a kind of tonal, painterly way for about the ten previous years, and I missed earlier ways of experimenting and playing. Coming back to the States in 2002 after living abroad for the previous ten years and seeing what was happening in the art world – I mean the enormous variety of media and technologies and techniques—I thought, well, hell, I could basically do what I wanted—that whatever preconceptions I had in my mind were just that: preconceptions. So, why not? I did a polyptych of a still-life in different modalities and called it one piece. And it went on from there.

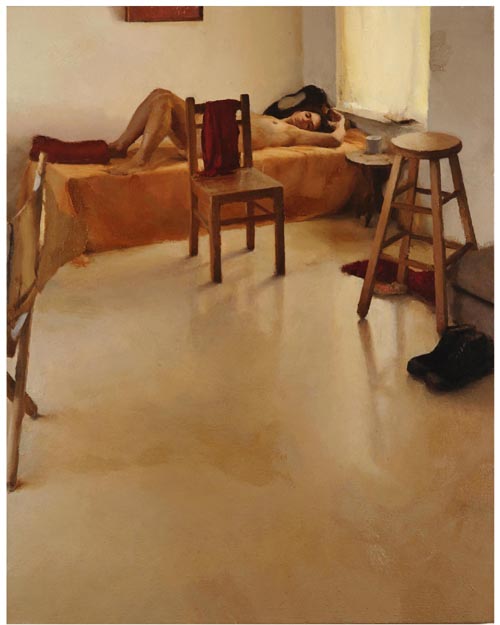

Woman with Director’s Chair, 2001, oil on linen, 50″x40″

Woman Reclining 10.27.11 III, 2011, charcoal on paper, 22″x26″

Interior 10.15.06, 2006, graphite on paper, 25″x22″

Interior 4.6.02, 2002, charcoal on paper, 25″x22″

When I first began to paint, as an undergrad, I had all kinds of foundation courses – among them basic representational painting and also the exploration of abstraction. My representational work was often gestural and painterly and sort of approximate in relation to the observed world. After ten years or so of painting, I developed a desire to really get my chops in terms of nailing what I saw, really honing my skills in terms of realist representation. That motivated my work strongly for about five years until I couldn’t contain the urge to bring back into my painting earlier ways of working, and now we’re in the mid-nineties. That integration was a difficult process, frightening at times. As I brought a more subjective way of painting back into my work in relation to a more realist mode it often felt like a kind of transgression or violence. It was a real struggle to find a way to stay intimate with the observed world and at the same time to bring my deep subjectivity to play in the actual touch and making of the work. I think it was Degas who spoke of the tyranny of appearances and the desire or need to work from drawings when painting, in order to not just copy nature but to make a painting, to make art. Eventually, in my mid to late thirties, after painting for fifteen to twenty years, I began to find a way of working that felt like mine. So this play with different styles or modalities or means of inquiry is an extension or a kind of acceptance of earlier confusions I had as a younger painter. I struggled for quite awhile with whether I was a representational or abstract painter. I was drawn strongly to both ways of working, suffered from the confusion, and wrestled with a split that in the end turned out to be a false dichotomy.

In terms of the switch itself, what that is like – one way that I think about it is in more classical terms, like the polarity of Apollo and Dionysus – or more analytic versus more sensual, or more task oriented versus more erotic. And I’ve come to allow myself these different energies while I work, enjoying them, these different ways of being.

For me this Apollonian/Dionysian polarity lines up with measuring/analytic/vision-at-a-distance/ achieving on the one hand, and gesturing/intuitive/close-tactile-touch/meandering on the other. So they end up corresponding to what looks conventionally as a polarity of representation and abstraction, but for me it’s all about keeping my level of engagement up. Lucian Freud spoke of that—of a painter needing to be truthfully open to his or her own desire.

So, it isn’t some kind of postmodern reply to the old representational/abstract dichotomy. That is, I’m not trying to present some kind of “progressive” resolution to a historic split (and it seems to me we’re in another one now – a split between a more aesthetic, object oriented location of meaning on the one hand and a more conceptual, philosophically—based location of meaning on the other – whether we’re engaged with embodied meanings as Danto suggests or conversely, meaningful embodiments. Although, taking a look at our current state of affairs it seems that the art market doesn’t give a damn about any of these distinctions anymore, as long as we can move product. So perhaps the split is being resolved through the good old bottom line). In the end, it’s just a matter of whatever most engages and motivates your temperament, gets you jazzed, turned on, deep into the work. There really is no “historical” progression anymore. So, when Richard Shiff writes about de Kooning’s “array,” he – de Kooning (and/or Shiff for that matter)—is perfectly suited to this moment. It isn’t so much that de Kooning is some kind of precursor to a postmodern aesthetic. It is more like this post-postmodern time we’re in has arrived, willy-nilly, through the eager tolerance of the art market, to a situation that tirelessly recreates the sense of discontinuity and disjunction that we find in de Kooning’s work – in individual works and in his overall oeuvre– that whole apparent split between abstraction and those figures. It’s as if our world is indeed “on the edge of something” and this constant sense of disjunction provides the opportunity to stay open to whatever it is that’s coming down the pike. I’m interested in this discontinuity —this sense of wholeness and lack of wholeness smacked together. Wholeness, as a human experience, lies outside of form, yet form can embody it and point toward it.

The tension in the discrepancy between the visual and the tactile can create a space in between that is neither visual nor tactile, but is a liminal space between form. I’m interested in that. It’s all a kind of inquiry/play – there isn’t any sharp distinction between any of these categories. There’s this wonderful quote from Shiff in his book on de Kooning, when he’s writing about Cezanne’s influence: “If either Cezanne or Gauguin had been making ‘abstract art,’ it was abstraction so intimately linked to the experience or representation of nature that any firm distinction became pointless.” That resonates for me.

With all these words, I don’t want to give the impression that I’m starting off with an idea—although I guess there is some of that to some extent – but more straightforwardly, I really enjoy picking up paint and putting it down in different ways. And I enjoy the experience of space developing slowly on a flat surface—and that development happening in different ways. And the play in my body and mind when I look from one image to another, of the same motif, in different modalities. Space is different. Touch is different. Being is different.

EH: How have your artistic goals evolved over the years since coming out of grad school at Yale?

JW: I’m not sure I had any artistic goals coming out of grad school! Maybe that was the problem! Well, I guess that’s not exactly true, but I’m not sure I thought of them as goals as much as “what’s next?” And for me, coming out of grad school, I was fortunate enough to go to a residency—the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, which kind of gave me a third year—to consolidate, clarify, and digest the whole grad school thing – you know, try to figure out what, from all the mess, is mine, and what was just pitched at me. So I guess that was important. Also when I left grad school I was still split between doing these pretty straightforward realist interiors and still-lifes and also I had these gestural abstract things on large paper. After the residency, I moved to Israel, and it was there that I worked, as I mentioned, to integrate these two impulses and interests into a common vision and pictorial language. I moved to Israel for a number of reasons. Part of it was a roots thing, heritage, my father was Israeli. Another part of it was this extraordinary energy and light and atmosphere that I found there—a sense of, well, of presence, of very strong presence. Call it what you will. And I wanted to live that, in a daily way. And that energy/presence/light/atmosphere became an important player for me, and participated deeply in the development and integration of my work. Life has led me to live in Colorado now, but I miss what I found and lived with there. I go back to Israel to exhibit and teach, but I’m looking forward to finding a way to spend some extended time there, working, painting — revisiting working there and going further.

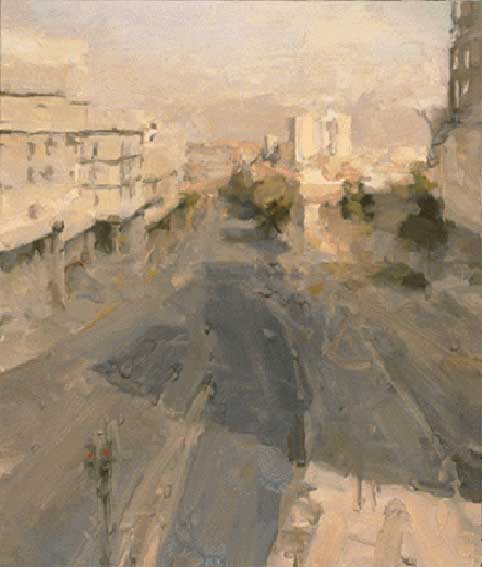

Jaffa Road, Jerusalem, 2000, oil on canvas, 66cm.x56cm. (26″x22″)

East Clinton and Moran, 2003, oil on canvas, 18″x22″

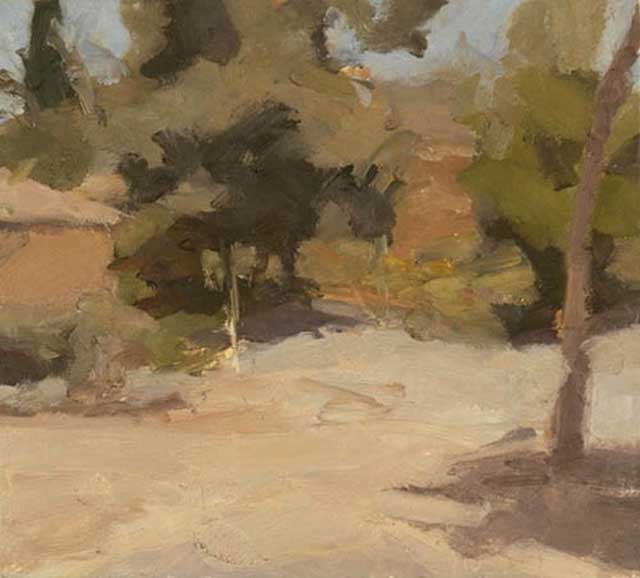

Kiriat Anavim VIII, 2002, oil on canvas, 18″x20″

Now what’s my goal? I guess I’d say to make work with enduring presence. And I’m really not sure what that looks like. I’m interested in exploring all kinds of motifs—landscape, interiors, figures— maybe self-portrait. And hopefully along the way some work will occur that really holds—that really gives. That would be good. And that my work might serve. That the work might serve to help kindle, reawaken us to ourselves. That would be mighty. In that sense my painting is my contribution to the great turning of the planet.

In relation to that last bit about contribution, there is also another aspect of your question that’s been coming up for me recently. It has to do more with the aspect of “ambition” than “goal”, as such. The first time I believe, that I had a conversation in my studio with my teacher, Andrew Forge, he spoke about the importance of ambition – not the worldly ambition of becoming famous but the deeper ambition of becoming a great painter. Andrew then told the story of how Matisse, when he was young and poor, spent almost his last franc on a small painting by Cezanne of bathers and had it up in his studio for forty years before donating it to the museum in Paris. Andrew paused and then said, Matisse didn’t have that painting up in his studio all that time just for inspiration – he was trying to out-paint Cezanne!

Now, I’m not really sure why I wanted to bring that in—but I love telling that story and it feels somehow relevant to your question and leads me, sort of, to what’s been troubling me. A few years ago I read the two volume biography on Matisse, by Hilary Spurling, which is extraordinary and I highly recommend. Anyway, while I was reading it I kept wondering to myself – what would Matisse do now? That is, given this man’s temperament and ambition, his talent and genius and truth and necessity—if he were alive today, say growing up in the conditions of the art world and culture that prevail today – what would he do? Would he even be a painter? What way of working today would make sense to him? What would his ambition be? Could he even achieve what he did — with painting being in the position it is in, that is, painting being such a rarified activity within the ocean of visual information that exists today? And recently I’ve been reading Shiff’s book on de Kooning and the same questions arise for me vis-à-vis de Kooning – what would he do today? What would that look like?

Because both of them cracked the world of painting wide open – and that meant cracking the art world wide open. And this cracking-open brought great, enormous vitality and life-force into painting, and into the world. Is the enormity of such a shift and offering available to us today? I find the question deeply unsettling, and though I don’t pretend to know the answer—I find the question also deeply saddening. Perhaps what I’m really trying to come to terms with here is, well, not just about the changes in the art world, but given the state of the world at large, given how fast everything is changing and the enormous uncertainty of it all, including the continued well being of our civilization and planet—to what extent does painting, does art, matter? What does it actually matter? Does it have an impact that adds up? It’s a spiritual question. And the ongoing corporatization of the art world underscores and sharpens that question.

EH: Those are gripping questions that I think every painter working today needs to engage with, if not answer, for him or herself. Thinking of you and your work, I feel like the exploration of “presence” ties into your deepest painterly ambitions. Could you tell me a little about what “presence” means for you?

Nataf—Dusk 2000, oil on linen, 12”x14”

Nataf—Rose 2000, oil on linen, 12”x14”

Rooftop Bakah I, ’98 oil on linen, 24”x18”

JW: So – presence. Yes, I use the word ‘presence’ fairly often to describe this essential something of a painting, or sculpture or really anything—not just art, but also art. But also places, people. Presence? Presence is life force knowing itself as being present. We recognize presence when we sense being. That is – life force meeting life force, ‘beingness’ meeting itself. We are it – just in a different form. Eckhart Tolle has a great section on presence in his book A New Earth. He does a great job explaining it.

Presence may be sensed through form, but it has no form of its own. Form can carry presence – not symbolically, although that may occur, but it is of secondary importance. The primary importance is that the form carries, embodies presence somehow energetically, vibrationally. And I’ve got no idea, really, how this happens. But it seems to need some kind of heat, catalyst, intensity, for this to occur. That is, for a person to imbue form with presence, the person needs to reach, internally, a kind of inner intensity – and that can come about through desire or strong emotion, be it dark or bright, or through concentration or mindfulness. But essentially there needs to be great life force in the making.

Then, if the viewer is receptive, the object can act upon them vibrationally like a tuning fork, and work to rekindle, to remind, to reawaken.

So, in this regard, what form looks like is really, oddly, less important than what goes on during the making of the form. Of course, it’s not quite that simple. It’s crucial and absolutely critical that part of what goes on during the making must somehow attend to and care for the form – in a very real sense, must love the form. I don’t mean “love” in the sense of “liking”—“hey, I really like this form!”—although of course we aim for something like that to occur, but I mean “love” in the sense of abiding next to and nurturing the form – giving love to, loving, the form.

Rooftop Bakah I, 1999, oil on linen, 22”x26”

Rooftop Bakah II 1999, oil on linen, 22”x26”

Interior in Three States, 2007, oil on linen, 28″x 93″

Jordan Wolfson in his studio photo by Elana Hagler 6/2012

Jordan Wolfson is a contemporary artist who has been teaching painting and

drawing for over twenty years. He received his MFA from Yale University School

of Art. Wolfson has exhibited extensively both in the States and abroad and

has received numerous awards including the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant,

the Ingram Merrill Foundation Grant and a Purchase Award from the American

Academy of Arts and Letters; he was a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in

Provincetown, MA and the Ballinglen Art Foundation in Ireland. Wolfson is

represented by various galleries including the DFN Gallery in New York City,

Rothschild Fine Arts in Tel Aviv and Artspace Gallery in Jerusalem. He currently

teaches privately and at the Art Students League of Denver. His work can be

seen at www.jordanwolfson.com. Wolfson currently lives in Louisville, Colorado.

Interior in Twenty-Seven Parts: An Extended Polyptych, 2010, various media, approximately 48″x692″

(clicking on image will bring you to see individual panels on artist’s website)

Still Life with Dried Flowers in Seven Parts, 2012, various media – charcoal and graphite on paper and oil on linen, 51″x88″

(clicking on image will bring you to see individual panels on artist’s website)

Interior with Red Carpet II, 2003, oil on linen, 48″x42″

These are some very beautiful paintings…luminous and dynamic. The surfaces seem very active with a buttery paint application. I would love to seem them “in the flesh”…

Also some very interesting ideas about presence and the intentions behind making.

I’m not sure you can separate an artist from his or her time (What would deKooning or Matisse be making if they were around today?) I think every artist, and artwork made, is a product of their specific experience in the world…a specific location, a specific decade, a life circumstance, etc. I’m not even sure deKooning would have made the paintings he did if he were not living in New York. I guess what I mean is it’s difficult for me to imagine the idea of a ‘time-traveling artist’.

Really great interview and thanks for introducing me to his work!

A fabulous and informative interview.

I find Jordan’s explorations into his heart, mind and brush, to be visually stunning with the added benefit of the viewer being allowed into a journey of discovery of their own.

Thank you for this insightful interview. I’ve admired Jordan’s work for a long time and had the good fortune to spend a week studying with him last summer. He’s a very generous teacher, a wonderful painter and interesting guy. I really enjoyed hearing more about what is at the heart of his work.

Thank you, again, for this wonderful series of interviews.

Hello Bill,

As the education coordinator at the South Shore Art Center in Cohasset, MA I have contracted with Jordan to conduct a workshop this summer, which is his second visit with us. May we use your comment above as part of our publicity announcing his return to Cohasset?

Tony

Wow! His paintings blew me away. Brilliant. Your interviews always amaze me. They always reveal the essence of the artist’s inner thoughts as it relates to their process. Thanks!

I’ve taught my drawing and painting students that the media and techniques we choose shape our theories and practices for years. Mr. Wolfson’s work will definitely be a resource for my future presentations. Thanks to you both.

Noel

I would say that there most definitely is a presence, or life force, in Jordan’s work. The viewer can feel it. Beautiful work and great interview. Thank you!

Excellent………….

Great interview!! I have always really enjoyed seeing Jordan’s work online, I wish I could see them in person! I feel like I got a much broader sense of his work from the selection accompanying this article, which I found very interesting. Thoughtful work, and an illuminating interview. And the painting of the Jerusalem street knocked my socks off! Beautiful.

This is a wonderful interview with amazing images – the work is very alive, every piece is treated with such delicacy, it is delicious to look at these works of art and I hope to see them in real life one day. Thank you.

I have seen the work of Jordan’s students and am astounded at the ability he has to pull students…into that place of true “soul.”. Stiff artists become more fluid and rigid styles become more fluid.

When I think of the meaning that goes into a Native American sand paintings for healing, I think of how much power there is that envelops the artist with a sense of “personal meaning” and “presence” in making the form….and how much power is then integrated into the painting itself so that a viewer becomes the recipient of that energy…through the form and layers of strokes seen and taken in.

I found myself writing down sentences on stick-em notes from this interview and then realized with more and more notes taken that I would have to affix them to a larger piece of paper. Some are worthy to be typed in large print and placed where one can see them while painting. (This interview is even more enjoyable between sips of coffee on the back porch in the early morning!)

Hello Nyla,

Jordan will be conducting a workshop for us at the South Shore Art Center in Cohasset, MA. Since I am the contact person for workshops and publicity, I was wondering if I could use your comment above to announce Jordan’s return to SSAC for another summer workshop? This will be his second visit and we anticipate the same strong response from our students.

Thanks .

Tony

Jordan July 26 12

Your Painting of Bakah really stunned me. I have never been there ,but you brought this wonderful place right to my door, my heart- the colours are so soft- and I could smell the place.

Former student

Nadine Hrywko May

I love the monochromatic paintings, particularly Jaffa Road and the unexpected bursts of colour found in paintings such as Rooftop and East Clinton super stuff