Interview with John Dubrow

by Xico Greenwald

John Dubrow has been making ambitious figurative paintings of New York City scenes since he moved to Brooklyn in the mid-1980s. His light-filled canvases are often years in the making—ragged, impastoed surfaces the result of the high standard Dubrow holds himself to. With a mid-career retrospective at the Demuth Museum in Lancaster, PA, on view through May 19th, and John Dubrow: Recent Work at Lori Bookstein Fine Art in New York, on view through April 20th, John Dubrow met with me in his Tribeca studio to discuss his recent work.

Xico Greenwald: You mentioned when we last spoke that there was one painting in your current show at Lori Bookstein that you worked on for a long time, an especially challenging painting. Working through the difficulties in that one canvas, you told me, ultimately helped you resolve the other pieces in your show.

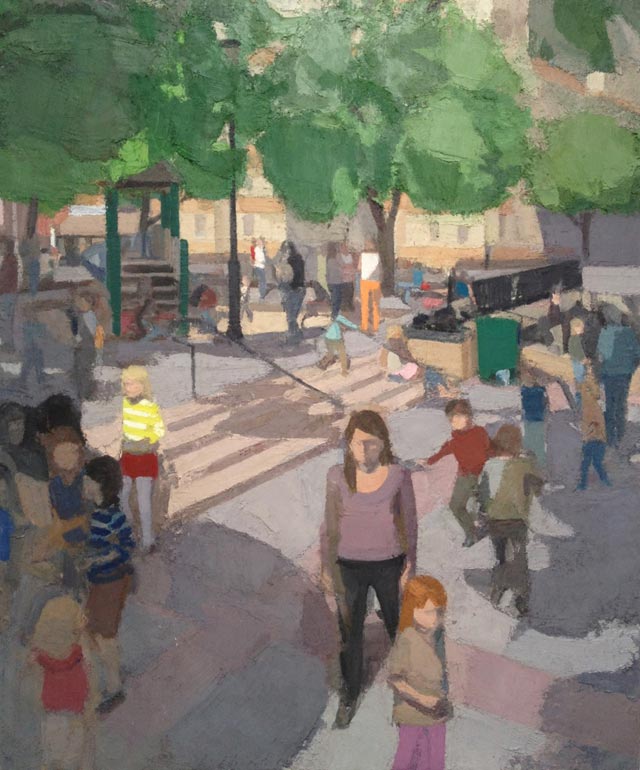

John Dubrow: The vertical playground painting, Standing Playground, Early Summer, 2012-2013. That’s the one with a female figure in the center and you’re looking down. That canvas ended up driving a lot of my other work.

XG: Can you tell me how that canvas evolved?

Sketch from iPad Courtesy of John Dubrow

JD: I started that vertical painting with my iPad sketch one day at the playground.

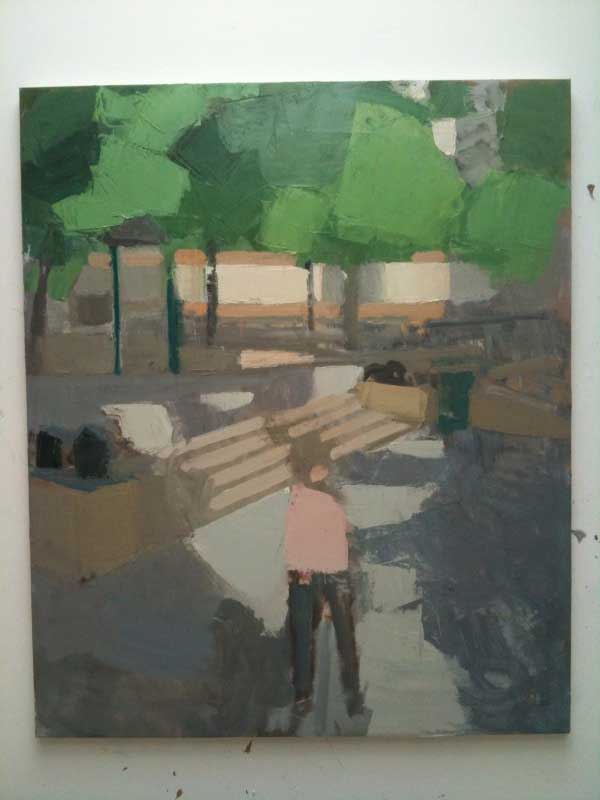

Then, with only the idea of a central figure, I blocked out the scene. This is from the first day of painting.

Courtesy of John Dubrow

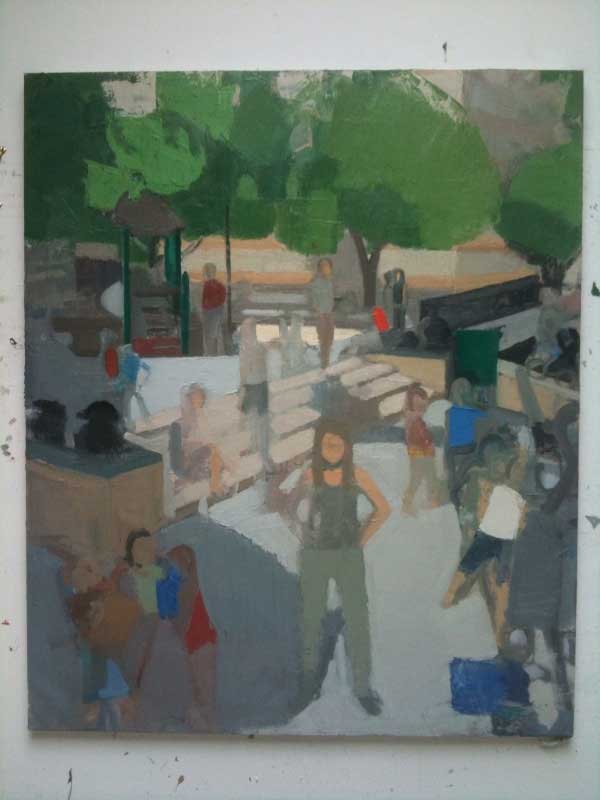

Then I thought, okay, I’m going to populate this thing. I’ve no idea how. I just began throwing figures in, both making them up and observing on site. Going everyday. So this is a few days later.

Courtesy of John Dubrow

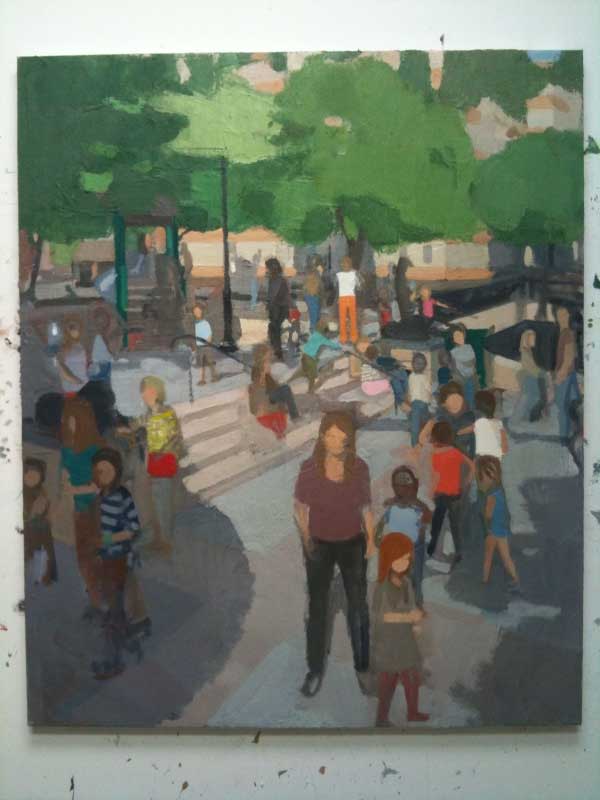

This is two months later.

Courtesy of John Dubrow

XG: But working like this, your painting changing so drastically, so often, do you never become attached to any one image? How do you know how to proceed in your work with no specific vision in mind?

JD: I’m waiting to get attached. As I get new ideas, I rework my painting. At points along the way I become attached to certain moments, different figure moments in the painting, and those are the things I start building on. It’s just an improvisation and until something locks in and I start building off that one moment, everything is up for grabs. There is usually a moment that is not necessarily held on to but that I can start building from.

A key moment happened in this painting two or three months into it, when, standing at the playground with my iPad, I saw a pair of orange pants walk by. I’m drawing all this stuff and all of a sudden I think ‘those orange pants are a perfect way to get you off of the central figure.’

Huge challenge to figure out these formal issues and, in a way, it’s the reason that I paint. For me the challenge of this particular painting was having a central figure that we lock down on visually. How do you then get off the central figure into the rest of the painting? I began throwing in elements around the playground to force your eye off of the central figure. The orange pants did that. But as soon as I put the orange pants in there I needed to find a way to get you off the orange pants. So I just began to systematically push you from focal point to focal point.

XG: So when you were laying out the scene that first day, all you knew was there would be a central figure.

JD: Yes. And, after struggling on this painting for a while, I actually thought I had lost the picture. Then a turning point came when, months later, I saw the Masolino Baptistery in Castiglione Olona, Italy. I realized this playground scene is basically a baptism and I put in this John the Baptist figure, here in red with his arm raised.

Standing Playground, Early Summer, 2012-2013 Oil on linen 72 x 60 inches Courtesy of John Dubrow

XG: What is it about Masolino you responded to?

JD: Masolino paints relief-like, flattened form with areas of deep space. Unlike Masaccio, Masolino, through a combination of patterning and naturalism, had an almost Gothic sensibility, just a hint of volume. Which is what I’ve been trying to do- have this thing where form is not fully articulated. The Baptism fresco, in particular, was as close to my own intentions in Standing Playground, Early Summer as I could imagine.

Whether it’s Christ or John the Baptist or the Madonna, in Early Renaissance painting there’s a hierarchy in those paintings. Before this playground canvas I had never had a streetscape with a central focus on one figure. My cityscapes and multiple figure compositions are about moving through space, the figures are locations to get to, colors and shapes, some with more importance than others, but, ultimately, parts of a scene. But I held onto the challenge of hierarchy here.

XG: And Masolino’s Baptism frescoes helped you with that?

JD: Yes. When you walk into that little chapel there’s a lot of activity but no doubt what is going on. All the activity relates back in some way to the central figure.

…And the way the space in Masolino collapses is insane.

XG: But that doesn’t happen in your painting.

JD: The space in my paintings doesn’t collapse. I would say that’s the most important thing to me- believable space made through color…. and the idea of compressing the space and expanding the space at the same time.

XG: I want to ask you about your choice of subject matter. For a few years, because of personal circumstances, you would sometimes accompany kids to the playground. Is that how you generally choose what you’re going to paint, freely incorporating your personal life into your artwork?

JD: Yes. It’s random events in my life. Wandering by a place that I might have wandered by a hundred times before and I look up and see something; I recognize a painting of mine.

With the playground paintings it took me a long time to understand the heart of the playground: the incredible movement of the place, things going on everywhere. So at first it was just a sort of landscape with intricate little forms of the children playing in the sandbox. As I kept going I realized there was more to it, pockets of activity, discrete from each other but combining into a big symphony of some sort, more true to contemporary life.

XG: What’s the role of art history in your work?

JD: I feel like this is my history. My goal is to somehow take my life, what I’m experiencing, and place it into this tradition with other artists from the past. Of course I want my paintings to be freestanding. But I also want them to be part of a dialogue. It’s a very personal, almost a spiritual engagement. For me this personal dialogue that takes place in my studio is the driving force behind my painting. And it wouldn’t be enough to just want to paint pictures of contemporary life.

XG: What do you mean by “dialogue”?

JD: Well because of Cezanne, I’m reading Titian and Rubens in a very different way. Because of Matisse I see Giotto through the lens of a 20th century artist. Every time a painter really sort of nails something, they enter into the dialogue and things begin to line up in a different formation. We see the world differently. I’m a person who, by being deeply committed to certain elements of the past, is trying to carry this conversation forward into the present. And it might not be a part of the contemporary conversation…

XG: It is not part of the contemporary conversation. And the people who you are conversing with are all dead.

JD: Yea. It’s for crazy people, this endeavor.

XG: Is it lonely?

JD: No. Never. I’m deeply tied into these people. Nothing lonely about it.

XG: And you have an audience.

JD: I think people respond to art that’s uncorrupted. So any interest that I have from the outside world is probably as much to do with that as anything. It doesn’t matter to me how long my paintings take, how many hours go into it. I may have to rip the painting open for years. And I think that there is something that gets into the work because of that, an intimacy that comes from my engagement.

In my show up now at Lori Bookstein, as the deadline for the show approached, the paintings underwent radical changes. With every piece in the show there was a dramatic ripping apart at the end. One more time going full bore as though it was the very beginning of the painting. It is really a ‘fuck you’ moment.

XG: Well surely at times, with a deadline pressing down on you, that process of “ripping apart” your work at the end results in bad paintings.

JD: Guston said a painting comes together in half-an-hour and you have to wait for that half-an-hour. And in my experience it is also the ‘half-an-hour’ in the end. But it’s a year or two years or three years getting me to that place where I understand so intimately the structure of the painting and I’m so confident that if, in the very last moment, I rip the shit out of it, that I can bring it back together in an interesting way.

It happened in that big vertical playground painting we’ve been discussing. I had this ‘fuck you’ moment three days before it was to be picked up for the exhibit. I began drawing into the central figure with ochre on this lavender shirt, reformulating the central figure. And then I began shifting things and taking out other figures in a complete frenzy and then… that was it.

I’m trying to get intensity, maximum engagement, in the very end of the painting. I’m trying to get it to have sparks.

XG: But weren’t there times earlier in the development of Standing Playground, Early Summer when the painting looked resolved? When it could have been finished?

JD: Julius Hatofsky, a teacher of mine in graduate school, would work on his paintings for ten years. He used to say painting is like taking a bus ride through the city. You can get off at any point. But if you keep riding the bus you’ll see some really interesting stuff. And if you take it all the way to the end of the line and then take it back you’ll see a lot more interesting stuff. So, it’s up to you when you get off. And it seems sometimes like I could work on a painting forever. You do one thing and a whole new world opens up and why hold on to the old image when you’ve got this new world to explore? For me it’s just an exploration in change.

More information about John Dubrow’s work can be found at his website and at Lori Bookstein Fine Art

More information about Xico Greenwald’s work can be found at xicogreenwald.com

Editors Note: Xico also wrote the March 14th review in the New York Sun, Long Looking in Lancaster, of John Dubrow’s current retrospective at the Demuth Museum in Lancaster, PA.

excerpt from the Lori Bookstein Fine Art Press Release:

John Dubrow was born in 1958 in Salem, Massachusetts. He received a BFA and MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute (1979-83), where he studied painting under Bruce McGaw and Julius Hatofsky. Since 1983, Dubrow has been based in New York City. His paintings are included in several public collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Dubois Institute at Harvard University, the Hilton Hotels Corporation and the National Academy of Design. He is the recipient of a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, the National Academy of Design’s Truman Prize and Carnegie Prize and the Port Authority World Views Project at the World Trade Center.

These paintings seem very playful, yet hard-won. I can pick up on the flickers of other artists he admires, and feel the pulse of art history coursing through his veins…I really enjoyed looking at his website and the body of work as a whole. Couple things that came to mind (questions?) for John, Xico, or Larry:

I’m curious about the Ipad sketches. I know a few artists that work things out this way, either as a kind of sketch book short hand, or as a more developed way to execute a finished image. How did this approach develop, as it seems that the paintings are very physical and tactile? I was just wondering because the media seems so new. The answer I’m assuming might just come down to practicality (i.e. it’s easier to sit down in a playground and do a color sketch with an IPad verses lugging a backpack full of gouche or watercolor etc to search for the same things) I was wondering if there’s a tactile difference that comes up in the process, and how John goes about transitioning from the screen image to the canvas image.

Also, I was wondering, John, if you could speak to studying in San Francisco, that is, did you find that there was a different approach to paint handling, subject matter, picture making that is ‘different’ than NYC? This has been on my mind as I just finished reading a bio on David Park (by Nancy Boas), and in it, what kept coming up was this East Coast-West Coast approach or mentality…again, not sure if this is one of those bullshit dichomities that are imposed by art historians, journalists, theorists, etc. but your work does have that ‘look’ or sensibility to the Bay Area figurative artists (but also Fairfeld Porter, too). Any thoughts on that?

Again, I really enjoyed your work and wish I could see these paintings in person….many thanks John, Larry and Xico!

Its all practicality. I used to bring a little sketchbook and pencil out with me, now it’s an ipad. The tactile thing I just don’t worry about- outside, whether in a sketchbook or iPad, its just about collecting notes. I check in on the notes pretty frequently in the studio, but am not tied to any of them. they are just memory aids. the paintings are pretty freely improvised as i go.

Don’t know how to answer the question about west coast vs east. I admire some paintings by Park and Porter, but I’m much more interested in painters from an earlier time, whether it be Venice 1510 or Paris 1910.

Xico, thanks for posting the first photo of John. If all you’ve seen of any given artist is self-portraits, one would think we’re a very grumpy bunch.

http://hiroyukihamada.com/blog/2013/04/16/paintings-by-john-dubrow

check out these fantastic close up photos of the John Dubrow show on the hiroyukihamada blog

Thanks again to Xico for putting the time and effort to make such a great interview

These detail photos are amazing. The painterliness and rugged surfaces totally do not come across in other reproductions. Great!

Really love the work and also the way John is talking about it, very down to earth which is reflected in the texture of the paintings.

The bus ride story is great …

It’s indeed the search and struggle that makes art so fascinating. You don’t get those sparks when you stop too early!

I also find Kelly Hicks’s remark about the grumpy bunch very funny.

🙂

JP

I love his work. Thanks for sharing!