I am very pleased to share this email interview with the fabulous Joan Wadleigh Curran, a Philadelphia based painter, who has exhibited in solo exhibitions at the Savery Gallery and the Seraphin Gallery in Philadelphia, PA., Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery in New York, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C. as well as many other venues. Curran has received many grants and awards and has been a Senior Lecturer in painting and drawing, School of Design, University of Pennsylvania since 2001 and retired in May 2016 in order to paint full time.

In July 2016 Stan Mir wrote in her Savery Gallery catalogue, Endurance

“…William Carlos Williams insisted “No ideas but in things.” Curran doesn’t paint the human figure. But she has nurtured every thing in her work. The ordinary receives her slow, methodical attention.

If an artist cares about what’s been cast off, where is beauty? It’s here. Right next to ugliness. They have always been siblings. In Curran’s work, one never taunts the other. There’s never an, Oh yeah, you think you’re pretty; wanna see how ugly I can be!

Curran’s eyes become our eyes. She’s always asking us to imagine this, except she never provides a narrative. Why would she need to? We’re already living amongst these things.”

– Stan Mir is a poet and critic. His writing on art appears in Hyperallergic Weekend.

In an Essay by Michael Lewis for Co-existence catalog from the National Academy of Sciences exhibit, Coexistence, 2008, Washington, D.C. Lewis states…

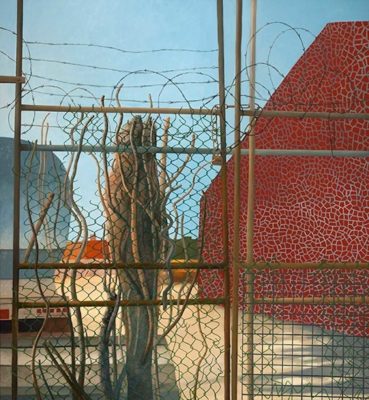

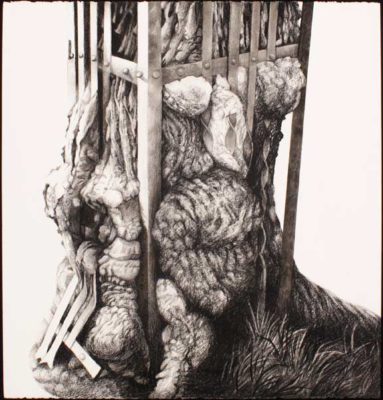

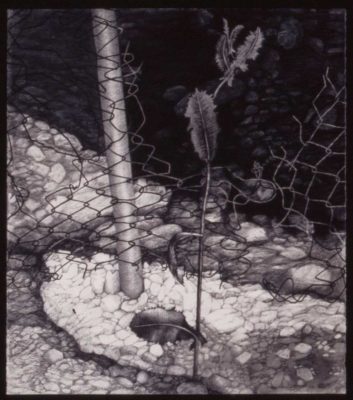

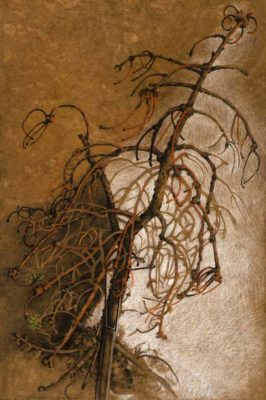

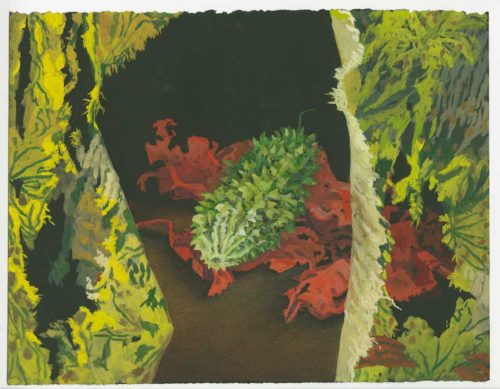

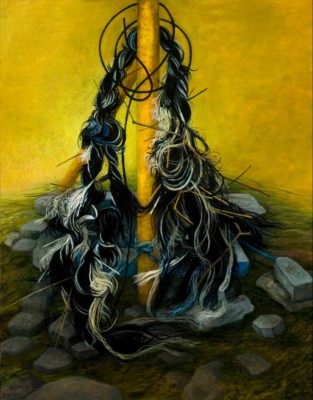

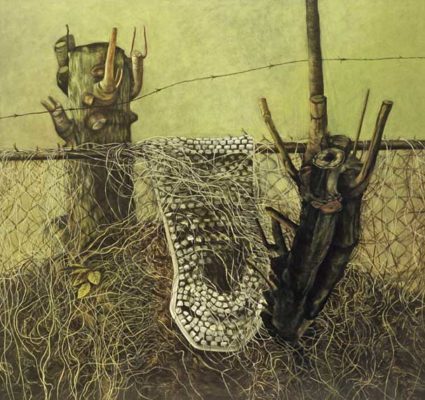

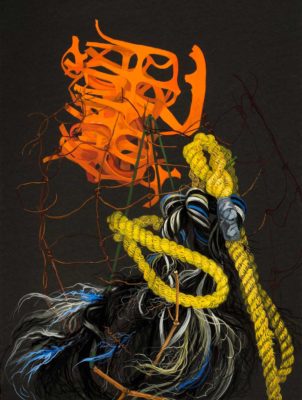

…she realized that industrial objects could serve the same role as natural ones, conveying life and freedom. The wisp of an impaled baggie in “Trapped” or the frayed plastic rope in “Along the Levee” are technically classified as litter but pictorially they serve as flowers: little declarations of life and movement and freedom amid the barricades and barriers that enclose Curran’s visual world.

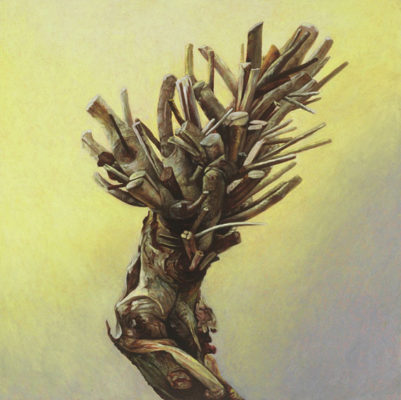

If Curran’s work is architectonic in structure, it also has a distinct and somewhat unnerving sacral sense. Objects that address us frontally and with solemn symmetry invariably suggest a totem or idol. Sometimes the allusion is more specific – the frayed rope and the plastic bag are carefully centered, and each has something of an agonized halo at its crown, suggesting flowers adorning an altar. To what or to whom that altar is dedicated is not made clear, which is one of the reasons these images tend to get under our skin and make us uneasy after a certain interval.

Curran is not the first American artist to seek a truce with our industrial civilization, or to find visual poetry in technology. One thinks of the Precisionists and Charles Sheeler’s paintings of vast automobile plants, or Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs of mournful skyscrapers. But their subjects were bold and monumental, and intrinsically heroic; Curran asks us to find beauty in the hateful and the abject. And for this there are few parallels, in painting or elsewhere. – Michael Lewis

I would like to thank Ms. Curran for her generosity with sharing this thoughtful interview.

Larry Groff: Please tell us something about your background and how you decided to become a painter.

Joan Wadleigh Curran: I grew up outside of Boston. As a child I loved to draw and make things. As long as I can remember, I was always fascinated with nature. One of my strongest childhood memories is the quiet of the woods, being by myself, and watching Flickers (a woodpecker type bird).

I lived in New Jersey until I was 5. Our house was next to a small wood, and I remember looking at Scarlet Tanagers next to our house, and of a Ring Necked Pheasant in the bushes by our front door. My father was from Maine, and every summer we spent two weeks at the beach in Ogunquit. I spent hours gathering rocks and starfish and exploring the tide pools. The intensity of those experiences is something I still seek in my work.

In elementary school I was selected for an art program outside of school. We went to the junior high school once a week to work on art projects. There I met Mr. Siemering, the art teacher. He made a strong impression on me because he looked and behaved like an artist. I have cerebral palsy, and I remember him visiting me in the hospital after I had surgery, and bringing the book Archie and Mehitabel, an adventure of an alley cat and a roach with illustrations by George Herriman. I somehow recognized that there was an alternative creative world out there that seemed much more interesting than the one I was familiar with.

In my public high school, the art studio was an energetic and creative alternative universe. It was here that I saw that it was possible to be an artist. I applied to RISD and a number of colleges with good art programs. I needed a scholarship, so when I received aid at Skidmore and not at RISD, I decided to attend Skidmore.

LG: What was it like for you to be an art student in the early 70’s? What kinds of painting were you making in your early years?

JWC: At Skidmore I was involved with drawing, printmaking, painting, and some hand built work in clay. I was interested in working across media and made paintings on paper, lithographs, drawings, and clay forms working from insects that I got from the biology department. I loved the intricacy and structure I observed in these objects, and the expressive possibilities of exploring this subject in a variety of mediums. At the time, Skidmore was an all-women’s school. It was an intense environment of serious art students. The environment fostered commitment and hard work. I had a number of teachers who encouraged me in my work. I had a passion for drawing, and decided to apply to grad school. I was interested in graduate school in drawing, but at that time programs were more rigid in terms of discipline. I ended up applying in printmaking since I had been making lithographs, and it seemed closest to drawing. Once I was at Yale, I wanted to draw and paint, but was told if I wanted to paint I should reapply in painting! I ended up doing most of my graduate work in drawing. At that time most of the teachers at Skidmore and Yale were male, and coming from a women’s school, I found the atmosphere to be rather “macho”.

LG: It isn’t uncommon to hear of painters who give up painting soon after finishing school. What has kept you painting over the years?

JWC: I am anxious and rather miserable if I am not working. Working in the studio is a way of engaging with the visual world and a way of thinking for me. I love looking, both at painting and art in general, and am turned on by engaging with and interrogating the world around me. Painting and drawing is a way to figure out how to use description, color, shape and form to say something about how I see the world. I find working to be materially and intellectually stimulating. Investigating both contemporary art and art history is challenging and exciting, a way to explore diverse ways of understanding the world.

LG: What are some of the biggest changes you’ve gone through with your work?

JC: I felt constricted in grad school because I was used to working in a variety of media. This is a commonplace practice in many grad programs now. But Yale’s program felt constricting to me. Grad school was a time of emotional upheaval for me. I was trying to figure out my interests and how to move forward. On leaving grad school I felt free to draw and paint primarily.

I moved to Georgia for a teaching position. I had been diagnosed with cancer at graduation time, so it felt scary to move away from everything familiar to a new environment with an uncertain prognosis. But it also seemed unwise not to embrace a new adventure.

After several moves for teaching positions and grants, I moved to Philadelphia. For a while I took a woodworking class and experimented with building complicated structures to paint on that consisted of panels with sculptural frames that integrated the two dimensional painted image with three dimensional elements. My work is very object oriented, and this was an attempt to integrate actual and illusionistic form.

As a woman who wanted both family and career, I had to figure out how to balance studio practice with the competing demands of teaching and family.

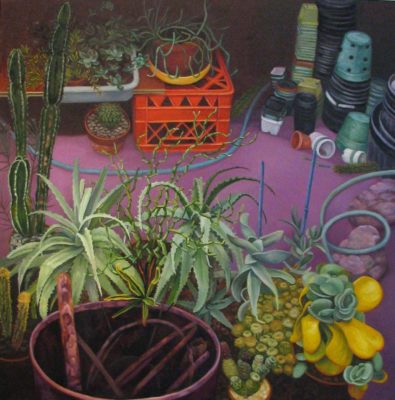

LG: Has your focus primarily been on still life painting, Why is that?

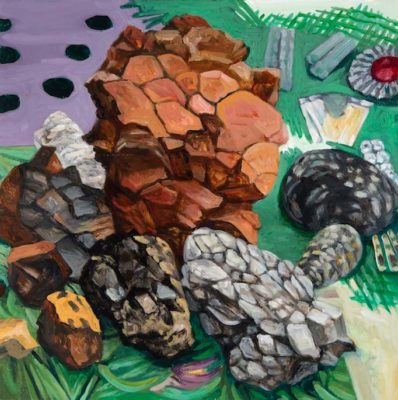

JWC: I think of my approach as a kind of hybrid involving careful description that incorporates still life and a kind of portraiture. I find objects seductive and hope for a kind of animism in how I paint them. I am particularly interested in the power of the object extracted from its local context. This allows me to manipulate composition and meaning. I am after a kind of intensity of engagement with the particularities I discover as I look and paint, and this process is similar to portraiture. My work investigates beauty and loss. I depict situations that embody contrasting states: beauty and ugliness, strength and vulnerability, and growth and regeneration. I seek a correlation between touch, experience and thought. My goal is to make a painting that questions assumptions and habitual ways of seeing. I am interested in an intimate, domestic, tactile investigation of subject by re-seeing the familiar in a new light.

I am interested in how objects can become transformational containers capable of describing other states by synthesizing the felt and the observed.

LG: How important is observation to your work?

JWC: Careful observation is of great importance to me. I have always been interested in specificity. As I look carefully, I begin to understand the powerful attraction of my subject and through painting try to uncover its mysterious presence.

LG: You often give yourself difficult drawing challenges with the complicated, tangled forms like the fibers in the ropes, netting and the like. What draws you to these forms?

JWC: Many of the forms that I paint have a connection to the body, things that were nurtured by people, or conversely discarded. The qualities embodied in the objects correlate to human values. Some objects envelop and surround us with their beauty, others show evidence of the passage of time and are informed by more uncomfortable qualities. In this way the objects become surrogate structures related to human qualities.

I am attracted to decoding complexity, finding a world within the complex visual characteristics found in my selections.

LG: What is the relation of your drawings with your work?

JWC: Drawing has always been my first love. It gives me access to the visual world and its seductions. It is rigorous way of making contact with the world. It is a way of gathering information and understanding how to translate information pictorially. For me, drawing is a way of thinking. It is a way of connecting emotionally with the subject, but it is also a rational and formal method of figuring how to express my ideas pictorially. My drawings are not preliminary studies, but as serious an involvement as my paintings. Because they are tonal and not usually in color, I am interested in the abstract formal qualities of composition, shape, value and edge. I have similar interests in my painting, but color, scale and materiality add a sensuous and exciting element.

LG: Can you tell us something about how you go about starting and making one of your larger oil paintings?

JWC: I like working from observation, and this involves collecting objects and building either simple or complex set-ups from which to work. Recently my process has changed somewhat. Once I have an idea, I begin to collect related objects from my environment. I have been using the Internet to expand accessibility to varied subjects. I create folders on the computer and fill them with images that I can use in the paintings. I make relatively quick gestural drawings to establish the composition and select individual objects from the collected images to insert as needed. This has allowed me to be more inventive in my approach as the paintings are a combination of careful observation and invention. I can enlarge an object, draw and change its orientation, and combine photography with physical objects in the studio. This has freed me to pay increased attention to pictorial construction. I often use a colored ground because immediately I get involved with color interaction. I don’t use a detailed drawing, because I want the painting process to feel immediate and this allows me to figure it out as I go.

LG: You also make many large gouache drawings. Why not paint these in oils? What is the appeal to you for making these?

JWC: I consider the gouache pieces to be paintings. What first attracted me to gouache was the color and attention to detail I found in Indian miniatures. I am fascinated with the intensity of the world created in these paintings. I am compelled by the abstract compositional construction of the image, and the purity of color and shape. I have a similar interest in northern European and early Italian painting. I like the tension between flat abstract shape and space. I also think this more flattened compressed space pushes the subject forward to confront the viewer.

Gouache provides a way to investigate painting that is related to drawing for me. I love working on paper, it feels very immediate, fresh and flexible. I also think there is something about the fragility of paper that I am drawn to. The disadvantage is presentation and framing. Framing, of course, is costly, but the glass and frame present a barrier between image and viewer.

LG: How important is naturalism to your work?

JWC: Drawing is incredibly important to me and I see it as a way of interrogating and understanding my subject. I am truthful to observation because it is through the process of drawing that I begin to understand what I am after. The more I look, the more amazing, complex and strange the world becomes.

Drawing, however, is also a way of understanding what should be emphasized and what can be suppressed or altered. I am interested in specificity, and hope that through careful attention and emphasis that there is a corresponding intensity of experience for the viewer.

LG: Much of your work sets up juxtapositions between natural forms like plants and the cast away forms like ropes, fencing, and netting. You set up objects that are contained or compressed into a shallow space. These strike me as unusual subjects and setups for still lifes can you say something about your reasons for painting these subjects?

JWC: I think my interests between people and the natural and manmade world began with painting pollarded and pruned street trees. Here nature was controlled by people and showed evidence of our desires and neglect. As I became more interested in the interaction between people and their environment, I had the opportunity to visit New Orleans after Katrina. I observed people’s personal possessions transported into the public space. I found these contrasts compelling. In my urban environment, I find ample evidence of the personal thrust into the public sphere. I am interested in how objects can become transformational containers capable of describing other states by synthesizing the felt and the observed. I look for the unfamiliar within the familiar and to reveal significance in the seemingly insignificant. I try to examine the instability of our contemporary environment as an indicator of our values. By describing both absence and material presence, I hope to highlight that which we have touched and treasured and that which we have abandoned, forgotten or lost.

LG: There is a remarkable sophistication of your compositions and formal, visual concerns however; the visual drama and suggested narrative of many of your works don’t seem overly restrained by modernistic notions of aesthetic detachment. Do you think it is important to also connect viewers on an emotional level as well as the visual?

JWC: I am certainly not detached in my process, quite the opposite. In the beginning I start with a feeling, an experience or idea. Then I have to figure out how to present my intent visually. This is somewhat more rational, a balance between the intuitive and the rational. It is this process that I find compelling.

I hope to make a painting that is thought provoking, visually compelling, and moving. A tall order! Hard to achieve!

LG: What are your thoughts about painters using their art as a way to speak out on environmental and other social concerns?

JC: I believe writing and social activism are more direct and successful avenues to political and social change. I do, however, think artists have a powerful role in making us all pay attention to new ways of seeing the world. Painting and other art forms encourage contemplation and reflection on complex and varied ways of experiencing the world. As such, they are windows into another person’s experience and an entry to a new way of thinking and seeing the world. Art can take us to a new place and open us to varied visions of the world that would not be accessible otherwise. I believe this is a profound and affecting force and influence.

Thought provoking and brilliant.

Very well done interview. The thoughts expressed are articulate and very moving. A joy to see the art work with this painter’s thoughts. Thank you.

Technically there is a large disconnect of color and color as light with the object and space in many of these paintings.