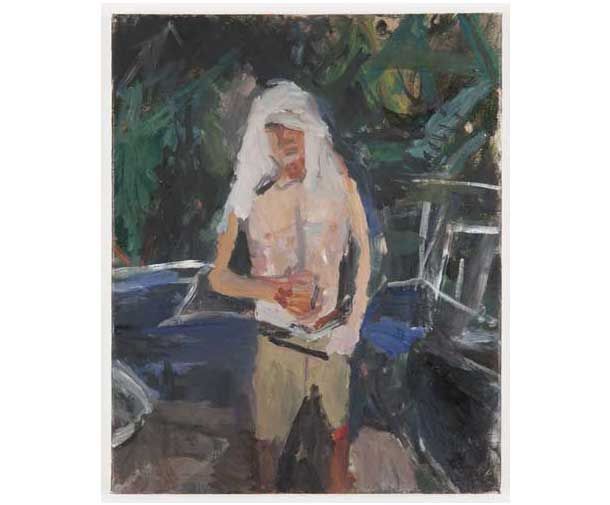

Janice Nowinski, Shrouded Male , 20″x16″, oil on canvas, 2012

click here for a larger view

by Neil Plotkin

Janice Nowinski is a Brooklyn based painter who currently has a solo show up at Bowery Gallery from May 22 – June 16, 2012. She is a member of Zeuxis and was included in the Common Object show. I want to thank Janice for her time with me in doing this interview.

Neil Plotkin: Your first mentor was Gretna Campbell. She had been a part of that second group of Abstract Expressionists who returned to figuration. That school is so quintessentially New York. You’re a born and bred New Yorker, and you did a lot of your studies here. On the other hand, when we spoke at your opening, you remarked that Manet is the painter you admire the most. Would you describe your work as a continuation and growth of the line of inquiry that the second group of Abstract Expressionists were looking at? Or do you see yourself as someone more influenced by Manet doing a twenty-first century interpretation of those investigations

Janice Nowinski I would say it’s a combination. Gretna really gave me my first exposure to painting issues. Before I studied with her, I really wasn’t looking at any kind of painting. I was just doing paintings. Yes, Gretna was a second generation Abstract Expressionist who studied with Hans Hoffman and that was a part of her teaching. She had another piece as well and that embraced 19th century and early 20th century French painters. She talked a lot about Corot, Bonnard, Matisse and also Manet.

In the eighties, the NYSS was largely about push pull and the geometry that took place within the rectangle. I was trying to integrate this and using my personal interpretation of the Hans Hoffman form of pictorial attack. I remember thinking, “I have to get the rectangle.” In fact the only pushing that was going on was me being pushed out of my own paintings. Gretna offered me an alternative approach that was really pivotal and liberating. I remember Gretna saying, “You can go from the center out. Bonnard didn’t even stretch his canvases until the end. The four boundaries of the paintings could develop as the image emerged. They were not a formal given. One can find the edges in other ways rather than painting from the outside in.”

Still Life / Gray,, oil on linen, 22″x30″, 1993

JN: When I was working with Gretna, my paintings were alla prima. They were quick, light filled paintings done from life. I would say they were more in the French Impressionist mode. This approach didn’t completely satisfy me. I felt I needed to deepen them formally and psychologically. I basically started working from still lifes which led to another body of work. The still life was really something that I could investigate over a period of time. I would start doing these paintings that often ended up being very long term. A couple of months, and then it turned into a couple of years. Back and forth this has been the thread that has evolved in my body of work for the last twenty-five years.

Still Life With Pears, 24″x28″, oil on linen, 2011

NP: You recently said in the John Seed interview, on his Huffington Post Blog, “If one is authentically involved in the investigation, the painting itself leads you into unexpected territory.” I suspect that you found yourself in that unexpected territory with these two new bodies of work that you have in your current show. Your work for the last twenty-five years has been mostly about working from the still life. Your process has been mostly to work directly from objects. These two new bodies of work seem to me to be a big break from this approach in that you’re working from photos. When we spoke previously, you said that this change of approach was very liberating. Can you talk about the freedom that you found in this new approach to your working method?

JN: It really was a big change for me. I still was able to look at something (the photo) but I wasn’t tied to what was in front of me and could invent more.

I went away from still lifes for quite a while, like eight or ten years, and I did a whole series of paintings from masterpiece paintings. I had done a little bit in museums, but actually working from the postcards served the purpose just as well. My investigation was not about understanding the techniques of the old masters but instead was a way for me to explore different subjects and most importantly to include figures and narratives in my paintings. I did many copies of multi figurative compositions including the Rape of the Sabine women by Poussin and the Raft of the Medusa by Gericault.

Raft of the Medusa, 1999, 30 by 20 inches, oil on canvas

Three Graces after Rubens, , oil on linen, 24″x18″, 2006-12

I began this new body of work using a live model. Quickly, I found myself distracted by the presence of an actual person. As a solution to this I found myself referring to photos I had taken of this particular model. I could work in a liberated way not dissimilar to the freedom I experienced when working from postcards of masterpieces as opposed to the original paintings.

Somehow, not having a live model in front of me freed me to make a different set of decisions which were surprisingly more personal, specific and emotive.

Seated Girl II, 13″x10″, oil on canvas, 2012

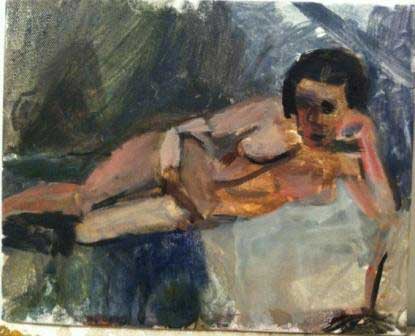

Reclining Nude 2012, 14″x11”, oil on canvas, 2012

NP: When we spoke, you said that there’s no certain amount of time that you need to work on the paintings. Some of your paintings are done over several years, and others come very quickly. For example, the painting Seated Girl II seems to have been heavily worked from the nude postcards. On the other hand, the painting Reclining Nude 2012 seems to have been arrived at much more quickly. What is it that brings you back into the paintings?

JN:

I would say what draws me back in is that they don’t feel right. I know that Reclining Nude 2012 was very quick, but it happened after a tremendous amount of work on other paintings. There were a couple of paintings that I didn’t resolve in time for the show. Those are the ones I’m working on right now.

There was one painting in particular that was completely driving me crazy. It really felt like the linchpin for this show. I was having one of those bang my head against the brick wall days. Then, on an entirely different canvas, it all began to make sense. In a rush of clarity I painted [Reclining Nude 2012]. I was shocked when the painting resolved so quickly. I was thinking, I have to respect that, and I’m going to leave it.

I feel like whenever something happens, it’s an accumulation of other things you’ve done. The fruit of the labor can come out in a different painting.

Now I’m starting to look at my painting strategies differently. From my initial “a la prima quick draw” approach to my more recent beating of the “dead horse/banging your head against the wall” approach. I seem to have come full circle. In completing the circle I can implement a combination of different approaches and that is liberating.

Vertical Still life, 36″x 22″, oil on canvas, 2011

NP: John Seed in his interview called you a “painter’s painter.” You opened at the Bowery Gallery last week with a lot of well-known painters there at your opening. What does that mean to you? Do you find that, that fuels you or your work in any way?

JN: Well, first of all, I was really thrilled to have all those great painters there. I mean, I was really moved and touched by that, along with the feedback I was getting from them. I felt like people really responded to the work. And that’s the most important thing, really, is if people understand what you’re doing.

To be a painter’s painter, is there a higher compliment? I don’t think so.

Girl, 8×10, oil on canvas, 2012

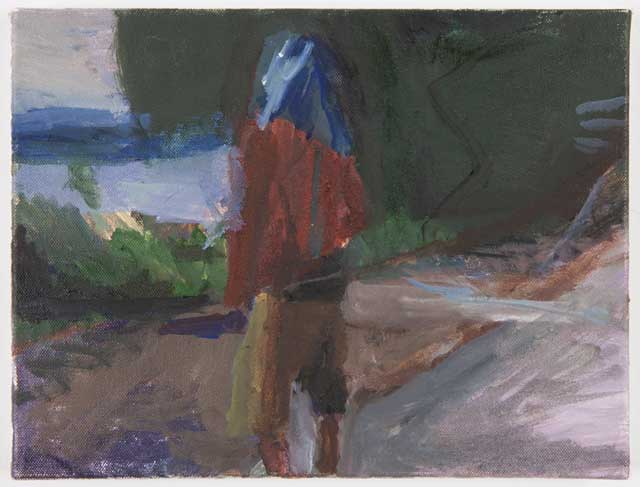

River, oil on canvas, 8x 10, 2012

NP: In your two new bodies of work, one of the qualities that I read into the subject matter is sexual desire. One is a male’s desire and the other is a female’s desire. The compositions are quite different. The women are in overtly sexual positions; whereas the men are standing or walking. Do you feel that this work is about different types of sexual desires that men and women have?

JN: Yes, of course it is. The way men look at women and the way women look at men is very different territory. Investigating and visualizing these differences was a stimulating part of making these paintings.

It is easy to find images that reflect man’s gaze and desire of women – less easy is to find the opposite.

Middleground, 10″x8″, oil canvas, 2012

NP: It seems that there’s almost no language for women’s sexual desires in painting—in the visual world, in fact.

JN: There really isn’t. That’s what is so personally engaging about what I’m tapping into. I can’t be the only woman painter who is aware of the lack of painterly language to address and talk about their own longing and sexual desire. This body of work was my first foray into this area. I have no problem with source referencing but in this case there really were almost no source references. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that the last transcription I painted was Narcissus by Poussin, which is all about a woman’s desire for an unavailable man.

Narcissus, 16″x20″, oil on canvas, 2010

NP: You mentioned that the postcard paintings were your Olympia paintings. It occurred to me that the women that you were painting could have actually been the exact women that Manet or other nineteenth century painters had used as their models for their paintings. I’m curious why those specific postcards intrigued you as opposed to other images of nude women. Like John Currin’s work you could say was from porn, and you could certainly say that Tillman’s Internet porn photos… Why did you choose those as a starting point?

JN: I chose the 19th century postcard girls as subject because of their anonymity and by today’s standards, they are clearly failed erotica. I picked them up because of that. It was a challenge to resurrect and return the sexual charge to an abandoned 19th century erotic postcard whose erotic edge has been dulled with time. I can’t imagine John Currin or Tillman finding inspiration here. It takes a woman to recognize the tragedy inherent in the loss of another woman’s sexual relevancy and the compassion of a woman painter to want to remedy it.

NP: It’s very interesting, because you’re trying to tap into a sexual charge of somebody from a long time ago, and then in the other body of work, you’re tapping into your own desires.

JN: Desire is a large territory for a painter. I feel like there is always a connection from long ago to now. That is why we still can be moved by Manet’s Olympia as well as Pompeian erotica.

NP: This is exposing to the viewers what your desires are, as opposed to a still life which is something that you’ve set up. You’re exposing yourself quite a bit more.

JN: The more authentic the painting becomes, the more vulnerable you make yourself. That is part of the job description./p>

Walking Man , 30″x22″, oil on canvas, 2012

NP: Where do you go from here?

JN: I’ll work on this group of paintings until the vein has tapped out. Every question I ask in the studio generates three more questions. If you’re asking the right questions, painting is self perpetuating and takes on a life of its own./p>

I agree with Janice that there must be some degree of difference between men and women on the “gaze” that has sexual overtones. Maybe painting is one way to explore this issue without demeaning women as object of sexual attraction. I find her works from the masters an interesting personal take on the formal issues imbedded in the images. Her gestural touch seems to give emphasis to the activity of painting, and her tonal palette keeps the works in a “drawing mode” for me. I had not been to her show, and wish I could have seen the works “in the flesh” since no reproduction does justice to the works.

Bill White

excellent university psycho-babble.

I thought Bill’s comments were perfectly pertinant. I like this work a lot; the still lives and transcriptions have a kind of spikey, nervous energy but the outdoor pieces have an ambiguity and open ended quality that is really attractive. Yopu cans till imagine a lot of possibilities for them. Many people expect art to be a complete statement, to be ‘resolved’,to be the last word – but art which leaves the question open (like Giacometti, for example) is even more interesting, at least for me. I mean, who ever saw a Cézanne that was fully resolved?

Stick figures do the job too….but what I speak of is the jaron.

Its not jargon; its perfectly okay language. I taught History and Theory of Art for 20 years, I know jargon when I see it. How do you communicate your experience of art without using language? When people complain about ‘art jargon’ although such a thing certainly exists, it often means they’re too mentally lazy to make the effort to articulate what exactly they’re feeling or thinking – which is okay, I guess, but it doesn’t really advance understanding much, either. If you like or dislike a piece of art you owe it to yourself, to the artist and to whoever is listening, to make the effort to explain why you think or feel this or that. Otherwise, you’re just expresing a personal preference, like choosing one flavor of ice cream over another. Who cares if you like chocalte or not? And anyway, there’s no reason why, in describing one’s experience of art, which is a particular kind of experience, one shouldn’t use a particular form of language that’s appropriate to that experience. The Greek word for describing visual art through the non-visual form of language is ‘ekphrasis’ and if it was good enough for Plato it should be good enough for us.

Impressive. Give me your ekphrasis on Yoko Ono’s dirt piles.

Fantastic paintings. Certainly a painter’s painter.

This is fine paining…..Janice gives us what we need to see…what engages us as a viewer to take the time to look and look again at a subject… really to look at a painting again…seeing more each time.

Beautiful work!

Hi, does anybody have any biographical information on Janice or pictures? Can only find her cv. My parents in law from the Netherlands think they have known her from way back.