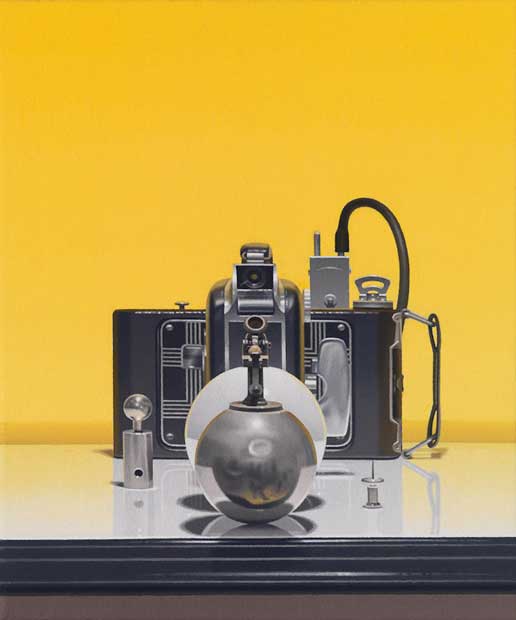

LIGHTER,LENS,CAMERA and BLUE WALL 2012 14X14 inches oil on canvas

click here for a larger view

Harold Reddicliffe is a still-life painter who shows at the Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York, NY and has shown at the Pepper Gallery in Boston as well as the Tatistcheff Gallery in NYC. He recently had a 30 year retrospective at the Boston University Art Gallery where an online pdf is available here. He recently retired from his position as an Associate Professor of Painting Boston University College of Fine Arts, where he has taught since 1987. I was fortunate to work with him as a Teacher’s Assistant while a graduate student at BU in 1993. His teaching, especially about drawing, was very influential to me in my growth as a painter and I am pleased that I can share a few of his thoughts to a wider audience. I would like to thank Professor Reddicliffe for his time and involvement with this interview.

Joshua Buckno wrote in his essay to the BU retrospective catalog Painting in the Age of Mechanical Obsolescence

“Reddicliffe’s depictions of cameras, microscopes, binoculars, and lenses refer to the accuracy of vision. Microscopes and lenses reveal minute elements hidden from the natural eye; binoculars allow observation of the fine details of distant objects; and the camera—once upon a time a magical and revolutionary contraption—captures a scene in time, not to mention time itself. All of these objects aid the human eye by allowing for a deeper and more precise ocular experience, while also serving as a reminder of the limitations of sight. Yet Reddicliffe’s paintings are above all a testament to viewing and perceiving objects, and the ability of the eye and hand to work together to depict an object with superb clarity, and limitless fascination.”

Larry Groff: Your paintings are richly detailed and highly resolved, but do not appear photographic. Your orchestration of spatial and shape relationships, treatments of edges and color interactions are very different from what a camera would see. Can you speak about the difference between what you do and photorealism? Why is observation important to your painting, and why not just use a photograph like the photorealist or make still lifes from memory like along the lines of William Bailey?

Harold Reddicliffe There are two very different reasons for each. In the case of photographs, as an undergraduate I did a lot of painting from photographs, and I discovered very quickly that the central pleasure for me in making observational painting has to do with the fact that one is required to take a three-dimensional object displacing actual space and figure out some way to translate that very specific 3-D language into the language of two-dimensional shapes on a flat surface.

And the thing, at least for me, that became problematic working from photographs is that the whole complex process that I’ve just very briefly described is already done for you. The monocular lens of that camera flattens the subject out, so you’re given the shapes that it has provided for you at the beginning of the process. So, for me, there was simply not as much enjoyment and certainly not as much difficulty, not as a great a challenge, as there is when one has to, starting with real 3-D stuff, make that translation into, ideally anyway, a persuasive illusion on a flat surface.

The other thing in a purely, I suppose, technical sense is that having binocular vision, one can choose to alter one’s station point fractionally. Even once a painting is started, if something is in any way puzzling or confusing, it’s possible by shifting frequently (as I’m sure you know) just a fraction of an inch up, or down, or side to side, to clarify the area in question.

All of a sudden something that is kind of mysterious makes perfect sense, and you can go back to the initial station point and then reevaluate those shapes from the point of view you are making the painting—with the additional information that came from looking at it from a slightly different point of view. Effectively for me, the answer to the photographic part (of your question) is it does too much of the job that I really enjoy doing in the first place.

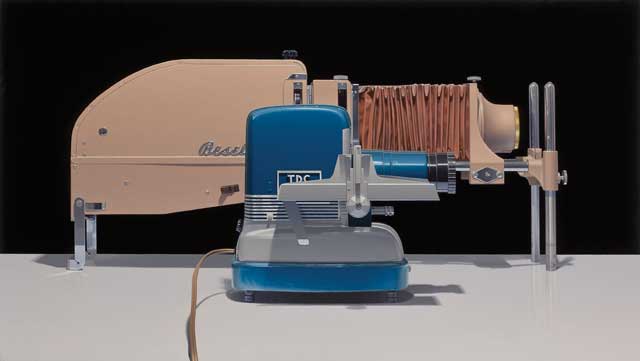

TWO PROJECTORS with CORDS 2012 12X18 oil

Microscope in a Box, 2006 Oil on canvas, 17 x 11 in.

In terms of memory, it’s a very fascinating issue, and it’s going to be a little bit more difficult to explain. One obvious aspect of memory is that detail is suppressed. One simply (or at least I simply) don’t have a memory that is sufficiently functional to be able to memorize everything that I’m interested in, in a complex object that I’m painting.

But more importantly for me, what I enjoy tremendously (as I was alluding to before) is that what this process ends up largely being about is the kinds of memories and associations that are conjured up by the specific analysis of the form over the course of weeks, or more likely months. So, in a way, memory enters into it, but it does so without the sacrifice of the kind of surface complexity that drives a lot of these paintings.

LG: Just to extend that question a bit more. The surface in a photorealist painting (where the primary emphasis is copying the photo) is often quite different than the paint surface from someone working from life.

I’m just curious. Your paintings are like in this weird place. They’re halfway in between. They’re highly resolved. There’s no clear mark of the artist’s hand in there. It’s not expressionistic. You don’t see the paint surface. But when you look at your paintings and the details of them—and I haven’t seen any of your work recently, but I saw a show a few years ago at the Pepper Gallery—even though you wouldn’t call it painterly, the surface seemed richer and different from the surfaces of photorealist paintings.

I’m curious. How does that fit into this process for you? I’m not sure surface is really the best word to use.

ICE CRUSHER WITH COFFEE POT 2011 12×12

Objects from Overhead, 2010 Oil on canvas 15″ x 12″

HR:

It’s something that has come up a lot, as you might guess, over the years. People who see those things, particularly in reproduction, assume that they’re derived from photographs. Part of it is a little bit contrarian on my part. I’m not (and never have) been interested in the kind of autobiographical element involved in the kind of handwriting that characterizes a lot of representational painting. I’m more interested in using the paint to figure out the image, and part of that, for me, has to do with suppressing a lot of the more abrupt transitions that occur when you’re concentrating on laying paint down, and instead, concentrating on the subtlety of the actual transitions that I see.

Surprisingly, I guess, there’s not all that much fusion of the paint on the surface with a brush. What it’s more about is breaking down the transitions that are occurring from shape to shape, from tone to tone, into the smallest possible increments. So, I suppose if you got up close enough, microscopically close; there would be some kind of painterly element. Because the individual marks stay kind of autonomous. I mean, each mark is a single decision—it’s just that there are lots and lots and lots of them going on.

I was painting a couple of objects involving spheres today. By the time I turned those spheres, I can’t even begin to count the number of actual physical marks that were made to do so, and I can maybe explain it even one step further.

In order for me to be able to control that process, what I’ve evolved over the years as a working practice is a very, very lengthy preliminary setup on the palette tonally. Within every local color that I use, I start off with between twelve to sixteen individual tonal mixtures, so that at any given point, when I’m trying to figure out a form, I kind of know where I am in the process.

And what it allows me to do, again in terms of the superficial smoothness of that surface, is break down, say, those fifteen that I’ve mixed on a given day into ten or twenty times more by working between each of the little mixtures that occurs on the palette. So it ends up being literally countless numbers of tiny, tiny increments of transition across the surface which adds up to, of course, if I’m even a few inches away, an apparently very smooth surface. Was that clear?

LG:

Very clear. I’m curious. What kind of brushes do you use with this?

HR:

I use all sable rounds, and they’re pretty small—from a number four up to about—every now and again I’ll use one as big as a twelve or a sixteen—but it’s mostly fours and sixes because of the intricacy of the object. And partly as a consequence, the actual size of the format of the paintings has reduced considerably. I mean, at this point, some of the paintings I made ten years ago would probably take years to do as opposed to months.

I’m finding that the more of these I do, the more fascinated I am by the apparently endless intricacies of the surface, and in order to allow myself the time to do that, I discovered I had to reduce the amount of area I’m trying to cover.

Ticket Stub and Envelope, 1987 Oil on canvas 8″ x 10″ oil on canvas

Pink and Green Envelopes, 1985 Oil on canvas 9″ x 9″ oil on canvas

LG: What led you to become a painter, and what are some of your most important early influences?

HR: I came from a background in which there was no interest in the visual arts at all. I grew up in Texas, and nobody in my family or friends had, as far as I was aware, any interest in that direction. However, like a lot of other people that ended up doing what we do, I had been drawing as far back as I remember.

When I went to college, one of the courses a lot of us decided to take (because the faculty was unusually good at that time in that place. This was at Williams College in the early sixties) [was] an art history course. And I liked it well enough that I thought, Hm. Maybe this is something I might want to do as a major. And it was back in the days when the art historians in that department believed firmly that people who wanted to become historians needed to know how the things they were going to be studying were made.

So, part of the curriculum was a studio component. One had to take drawing courses and design courses, and it became instantly clear that I liked that even better than the art history. And to my great pleasure, about two years into my stay there, they started a concentration in studio, which was essentially just an add-on to the art history. Most of us at the time ended up with what amounted to an undergraduate art history degree, but we were able to focus on the few studio courses that were offered. And on the basis of that, I decided to [move onto] graduate school.

In terms of influences, a little bit more complicated. As you might guess, in the early to mid-fifties in Houston, there was a relatively small collection. That’s changed dramatically since then, but I do remember seeing at the Museum of Fine Arts there (on my way to and from after school drawing classes) what I hope I’m remembering correctly as the Kress Collection which was a gift from the Kress family, of Old Master paintings. And then there were a couple of shows that coincidentally were there when I was doing this course that I remember made an incredible impression. There was a Magritte show sometime in the fifties in Houston which was, of course, unlike anything I’d seen, and it was memorable, to say the least.

I didn’t really start to think about influences in a serious way until I got to college and in my freshman year began going to New York with some frequency. I made it a point every time we were there to go usually to the Met and to the Frick and to the Museum of Modern Art. And it started almost, now, a fifty year involvement with those collections.

PORTRAITS #2 1998 24×36 inches oil on canvas

24 OBJECTS 2001 11×17 inches oil on canvas

HR: And very shortly thereafter, in a book store in Williamstown (this would have been in 1968) I ran across a catalogue to the Whitney “22 Realists” show that was in 1968 and became very superficially acquainted with people I got to know a lot better later, like Al Leslie, William Bailey, Philip Pearlstein and that whole group.

And I was entranced immediately by that. The idea that people could actually make a representational painting as serious grown-up artists was thrilling, because certainly the instruction we were getting at school was basically by people who had, themselves, gone to school in the forties and fifties, so the emphasis was very much on abstraction at that point.

If I had to pick two people out of all the people that I enjoy looking at that made initially the biggest impact and have continued to, I would pick Chardin and Morandi. They still are primary sources, just for encouragement, if nothing else.

LG: I remember you showing the graduate class I took with you to Harvard’s Fogg Museum where you showed us the Chardin drawings there. [You] actually got to hold it, I think, with the white gloves, if my memory serves me correctly?

HR: Right. Yes. It’s really an astonishing resource. I’ve done that pretty much every year since then (the drawing study) and to my great good fortune, one of my students ended up getting a job, there, and was the person who was actually delegated to bring the drawings out. He was incredibly helpful, because he’d taken the course I was bringing the students from, so he could sort of intuit what I wanted to talk to them about.

The difficulty is the Fogg has been closed now for several years, and it looks like it’s going to be another two before they reopen it. So that resource has not been available. It’s been a huge, huge loss. They’re completely redoing both the Fogg and Busch-Reisinger, and it’s scheduled to reopen now ( originally it was going to be 2013 ) in 2014. So, an institution much missed.

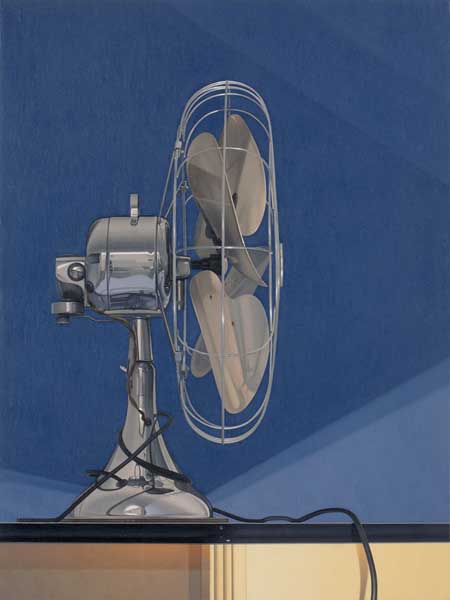

Jenny’s Fan 2006 28X21 inches oil on canvas

Lighter, Lens, and Engine, 2009 10×12 inches Oil on canvas

LG: You’ve been an associate professor in painting at the School of Fine Arts at Boston University since 1987. Walter Murch also taught painting at BU back in the early sixties and painted many still lifes of mechanical and scientific objects. Murch’s realist style is very different than yours, but there are similarities in the subject matter as well as the interest in abstraction of carefully observed and arranged setups. I’m curious if you might have anything to say about Murch’s painting in relation to yours.

HR: It was a startling revelation. When we were senior art history majors at Williams, the class was taken to a local collector’s house. He had been putting together American paintings for like thirty or forty years at that point. His collection subsequently went to the Whitney and the museum in Williamstown, the college museum. But among the paintings he had were two Murches.

The one I remember the most vividly is one about the lock, the interior of a lock. And I was riveted by that painting that day; but, he was somebody that nobody else that I knew was aware of, and nobody on the faculty, at that point, had any particular interest in. So, the image stayed in my mind, but I’m not even sure at that point I knew or remembered his name.

My first teaching job was in Columbus, Ohio. One of the other instructors there turned out to have gone to BU as both an undergraduate and a graduate student, and he studied with Murch. [He] had a lot of reproductions of his work, and had years of stories about what studying with Murch was like. So, secondhand, at that point, he became really an enormous influence.

I don’t really think I understood completely, at that point, because we didn’t have available to us the actual paintings to look at, as to exactly what was going on, particularly in terms of how their surfaces were handled. I sort of understood what he was up to, but without being able to see numbers of those paintings—it wasn’t until years later, when I saw at least a few, that I sort of got it.

I think it was probably gone by the time you were at BU, but he had left one painting that was still hanging in the visual arts office, and it was the first time I really was able to see how the surfaces looked. Apparently that story about the paintings being put down on the studio floor and walked on was not apocryphal. He really did do that. The connection to the New York school abstract painters was really very obvious, and I was fascinated by the tension that was created between those heavily worked and abraded surfaces and the remarkably specific and accurate depiction of those objects.

The question that I still have in my own mind is what the relationship between that surface and the kinds of objects that are being described is or should be? I mean, I’ve obviously come up with a totally different answer to the question, but I was fascinated that he was able to sustain that really active, heavily worked surface and, at the same time, seemingly not sacrifice any of the accuracy or the description of most of those very, very complex (a lot of them anyway) mechanical objects.

LG: The retrospective at the Whitney Museum that I was telling you about of his work included many of the still life objects themselves, that they displayed along with the paintings.

HR: Wow. I would have loved to have seen that.

LG: It was fascinating to see how closely observed they were.

HR: I think, too, when one has an opportunity to see the drawings, you can see just how precisely and specifically analyzed those objects were. Some of the paintings he made [for] Fortune magazine covers (if I remember correctly) are a little bit tighter, a little bit less heavily worked than the studio paintings were. You get a sense that one of the things that underlies the whole enterprise for him was a meticulous and very responsible response to those objects. He clearly had a real passion for them as objects.

LG: The passion is clearly visible that drove him to the lengths that he went to.

HR: I think the similarity (if there is one, aside from the subject itself) has to do with the whole really complex question of what happens when you take an object like that (a carburetor or a sewing machine which has a very specific, utilitarian function) and remove it from its functional context and just look at it for months, which is what I have to assume he did, and it’s certainly what I do. And I think one of the reasons that drives the process (for me, anyway) is to begin to become aware of the changes that take place in one’s perceptions of the object and the associations that one might have with it over the course of time that one spends looking at it.

TWO PROJECTORS and EXTENSION CORDS 2008 16×16 inches Oil on canvas

PROJECTOR and LIGHT STAND 2008 18×16 inches Oil on canvas

LG: In a bizarre way, perhaps its like the movie with Tom Hanks, Cast Away, where he forms a relationship with a volleyball, and it becomes almost a love interest, in a way, because through the isolation and concentration of that being your sole source of visual interest… Perhaps a similar thing.

HR: It’s very similar, and what’s fascinating to me (and I think it’s one of two aspects of this, right now, that continues to be riveting) is the fact that you know what these things are. I mean, just using a projector as an example. It’s perfectly clear what its function is, and the longer you look at it, of course, you can figure out how the particular projector is designed and constructed to perform that function.

But as you look at it longer and longer, it’s almost like (if this makes any sense) saying the same word over and over and over again, until all of a sudden it isn’t denoting anything anymore. It’s just sound. And you look at this object and realize that it has become completely free of meaning and that there are other associations and consequently new meanings that become possible.

And the trick, of course, is as this process plays out, not to try and force them. To try and see, once the original utilitarian association begins to fade and you’re used to it in this new context of it being set up in your studio with a light on it but nothing else going on, what it begins to remind you of. What other associations might drift in and take over.

The only risk (and I think you mentioned this in one of your other questions) is to try and control that metaphor. If it’s going to happen, it sort of does—and if it’s too thoughtfully or intentionally directed, it can end up being just a really embarrassingly bad cliché.

DEVICE 2003 21X14 inches oil on canvas

ICE CRUSHER 2011 14×11 inches oil on canvas

LG: Like most great still life paintings, your work seems more engaged with formal abstract painting issues, and less about metaphor, nostalgia or the sentimental. However, your work doesn’t seem overly detached or stiff. Occasionally there are subtle hints of anthropomorphic forms that suggest another level of meaning, and there is a richness and sparkle to your color, as well as the visual geometric dramas of the setup. Many of your subjects (like the cameras, slide projectors, movie projectors and lenses) have to do with mechanical forms of vision. Can you tell us something about why you paint these still lifes the way you do?

HR: I paint them the way I do for a couple of separate but linked reasons. The first part of the question is right on the money in terms of the formal aspects of it. Almost all of them are generated by an initial, formal problem or problems I set for myself.

It can be something having to do with the actual nature of the object itself. That’s frequently the case. But it may have to do with a formal problem I have taken from some very different source—architecture, frequently. I’ve also been doing a lot of looking, the past few years, at prints (both European prints and Japanese prints). There are issues that come up in those that I find very interesting and amusing to try and translate into similar kinds of problems in the paintings.

But essentially, all the initial decisions are made on the basis of things like two-dimensional organization, color, surface, texture, and how those things interact with each other on what I imagine as the painting’s surface. So, this may get into the question that’s further along, but the way they’re actually organized is I set these objects up and play with them for sometimes weeks at a time before I make a commitment to the image to see if I get them to do what I would like them to. And very specifically the goal I set for myself, from a purely formal standpoint in these paintings, is what amounts to a visual pun.

I’m endlessly fascinated by the idea of taking, as I mentioned before, a real three-dimensional object or objects and translating them on to a flat surface so that clearly the reality of the object I’m actually making (the painting) is that surface, and the flat shapes on it. And the illusion is how those flat shapes can be reassembled into some reference to the original subject that I started with. And I’ve done everything I possibly could think of to try and conflate the two, in the painting process, so that one is reminded constantly of the fact that no matter how persuasive the illusion might end up being, if it works, it is finally only a bunch of patches of color.

And simultaneously, when that’s being pushed—when the idea of these two-dimensional relationships has taken primary focus in a painting—it’s very important to try to do nothing that would undercut the viewer’s ability to still read these shapes as a very specific illusion of equally specific three-dimensional forms. So there are a lot of conscious decisions in lots of the paintings to create a real visual pun.

LG: Tell us a little more, Do you do studies at all? Do you draw directly on the canvas once you’ve finished setting up the still life?

HR: More often than not, there are no studies. Every now and again when I’m not actually working, I will just do very casual drawings to think up possibilities of things I might actually want to set up in the studio.

The best example I could give you is frequently during a break at school (when I was teaching) I would think of an idea that I might like to try and make a painting about, and just do a little, quick, informal drawing of that. But when I actually set about making a painting, I have to have made a decision about the objects that are going to be in it.

I set them up, and I spend up to two weeks (sometimes longer) adding and removing the objects, trying to figure out the point of view from which they’re going to do what I’d like them to do the most successfully, and I spend a roughly equivalent amount of time just sort of fooling around with the light to make sure that it clarifies them in ways that I find workable.

It’s all done with incandescent light. I don’t use natural light, at all, so I can control what’s going on. I use one spotlight for ambient light to paint in and another one focused on the setup.

So most of the work, in a lot of ways, is the result of just giving myself permission to play with these objects for as long as is necessary before I actually commit to the painting. I use a framing device to figure out how I’m going to organize it two-dimensionally, and I do a very, very lengthy line drawing on canvas. That can take as much as half the total time that the painting takes.

LG: Did you say you use a viewfinder? Is there some particular setup that you use for your viewfinder?

HR: I can’t remember whether we were using them in the drawing class at BU. Actually, I use two try squares to make a rectangle of the size I think I want the painting to be. Then I find the X and Y axis, so I can really hit the middle of it, [and] so I know pretty much, before I start the drawing, how everything is going to be organized. And then the very first thing, in the drawing, is a drawn vertical and horizontal axis, so I know where the middle of the canvas is and know where I want to crop the objects by the four edges.

LG: You don’t really use a grid? Or just the one division?

HR: Just the two axes. Just a vertical and a horizontal. So I’ve got four quadrants. And then what I try and force myself to do (for a reason I hope I can explain) is that for the first week or two I’m working on this drawing, I draw as loosely as I can—just sort of at arm’s length, barely holding the pencil. It’s very open and very general, at the outset, so that I can make sure that everything that’s going to be in there is pretty much on the surface, where I want it to be.

And then progressively, as the drawing proceeds, I allow it to get more and more specific, and toward the end I use the whole range of drafting tools that are necessary. I use straight edges and compasses and protractors—anything that’s necessary to get these things nailed down.

But I discovered years ago that if they’re used prematurely, I can persuade myself because of the accuracy (or the superficial accuracy of the kind of marks that they make) that the drawing itself is accurate. And it turns out it’s much, much easier to make sure that the scale relationships, the foreshortening and the perspectival issues are dealt with freehand just from my own perceptions. The drafting tools are really just a neatening-up process at the end of a longer-drawn process.

PAPER,PROJECTOR and PORTFOLIO 2006 24X16 inches oil on canvas

LG: I see.

HR: Essentially the whole point for me is to get a relationship established between first the shapes (via the drawing) and then a relationship established between the pigments that I’ve used, and the tones that I’ve mixed with those pigments, and the actual setup. When I’ve gotten that far, I have a series of comparisons that I can make. I can look at a decision I made about color with reference to the actual color I’m looking at, and then in the overpainted layer, I can do my best to adjust that.

LG: One thing I remember most about your drawing class at BU was your discussions of the importance of seeing the horizontal and vertical relationships correctly. To not draw elements in isolation from each other. You talked a lot about Antonio López García’s concern with this in his drawing of the quince trees. Also William Coldstream and Euan Uglow took this careful measurement, relating elements spatially to the extreme, and [this] was central to their art. Do you have similar concerns in your painting?

HR: Exactly similar concerns. In the sense that, as I talked about a little bit earlier, the idea that no matter what else this thing that you’re making might be—what it really is, is a flat object with flat shapes on the surface. And the whole point, it seems to me, is to be incredibly thorough and responsible about relating those shapes to each other. I think what makes it enormously both difficult and entertaining is the idea that shapes that you’re working with result from having to translate three-dimensional relationships into two-dimensional relationships.

So, that whole process of using lines extended across the surface of the painting to relate objects to objects quite a considerable distance away and relate everything to the four framing edges of the rectangle takes place nonstop throughout the whole process. That ends up being corrected over and over again as the painting plays out.

LG: It interests me that it’s so mercurial, like you said previously, that just altering your head a quarter of an inch can change that whole relational dynamic…

HR: Everything…

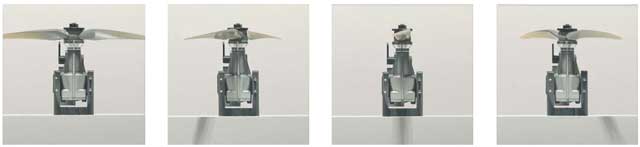

Engines and Reflection, 2009 Oil on canvas 8″ x 8″

LIGHTER and LENS 2007 12X9 inches oil on canvas

LG: …so how do you really decide? If you want something that’s from a different position, and then you have something from another position, how do you keep track of it all?

HR: Pretty much the whole two weeks of playing around with the setup has to do with trying to make sure I’ve established a station point that’s going to work. I close one or the other eye, and once things start to fall into place two-dimensionally, what I do is pick some set of relationships in the setup that I always go to back to, to make sure everything is lined up.

And a lot of really basic stuff. I mean, I mark the chair I’m sitting on, on the floor. I mark the easel. The elements in the setup are marked. I do everything I can to make sure that once that initial station point is chosen, I can successfully maintain it throughout the process of the painting.

That’s not to say, very importantly, that while the painting is taking place, I don’t move my head a lot, and change that station point, for reasons I talked about before, just trying to make sure that I’m able to figure out everything that’s going on. But I make sure that I’ve got parts of several objects that are lined up with one eye closed two-dimensionally, that I can use as a reference, a constant, throughout the whole process.

Twelve Keys, 1998 Oil on canvas 8″ x 10″

LIGHTER, LIGHT BULB and CAMERAS 2010 12X10 inches oil on canvas

LG: The art critic Jerry Saltz said a few years ago that, “All great contemporary artists, schooled or not, are essentially self-taught and are deskilling like crazy. I don’t look for skill in art. Skill has nothing to do with technical proficiency. I’m interested in people who rethink skill, who redefine or reimagine it: an engineer say, who builds rockets from rocks. I am looking for what the artist is trying to say, and what he or she is actually saying, what the work reveals about society, and the timeless conditions of being alive.”

With ideas like the above being prevalent in much of the art world and schools today, how has that affected a school like BU who has a great reputation for teaching fundamentals of figurative painting? And what would you recommend to a young painter who wanted to learn how to paint in the figurative tradition?

HR: It’s a very complicated question, and everybody who is teaching anything that can be even roughly described as traditional disciplines has got to grapple with it. I can only assume that things are as plural in the visual art world, right now, as have ever been in its history. And I think students, in a way, have got to take the first initial step in that process.

You know, we get a self-selected group. The students who come to a place like BU (and a lot of others still out there) have made a decision that they’re interested in learning some of those more traditional ways of making a painting. Obviously, there are an infinite number of other possibilities. People who are interested in various sorts of new genre art are very unlikely to choose a place like BU in the first place.

LG: New Genre Art, what is that?

HR: The whole range of conceptual, performance, installation or site-specific work—BU would probably not be a place that they would choose to go in the first place. There are just too many other art schools out there that are now focusing almost entirely on new ways of defining the visual arts.

In a given year, when a bunch of students show up from high school, I make the basic assumption (I think all of us do) that they’re there because they really want to learn something about drawing and painting. And by and large, that’s true. So you start from that. The more complicated issue, of course, is because these are very bright people, and they are not ignorant of what’s going on out there I think you ultimately have to be in a position of trying to make some sense out of why this is still an important, viable way of making form.

It’s tricky. I think you have to try and make a compelling case for the notion of the primary responsibility of the visual artist, even today, is to actually be able to make form. I think what’s really tricky is that just reading the Saltz quote (and you run into its equivalent all the time) the notion is that what’s important about an artist is what he or she thinks or feels or has to say about the society or the world at large.

My argument is, maybe not so much. I think what’s important is that people who have decided to be visual artists are the people who have committed to the idea of being capable of making a form that allows them to communicate those ideas or thoughts or feelings in the most memorable way possible. Simply talking about those ideas, I find, totally insufficient. I think the trick is to be able to make something that allows you to encode in its language what it is you think or feel about the world or anything in it. And that’s where the skill part comes in from my point of view.

I would agree with Mr. Saltz absolutely that skill for its own sake is largely pointless; but skill used in an effort to try to control the process of constructing form that you’ve chosen I think is critical—as long as one keeps in mind that it’s not the end of the process, it’s not what the process is about. It’s simply the means by which that process can be facilitated.

I mean, I’ve spent more time than I suppose I want to think about telling students year after year that their job specifically as painters is to be able to make a painting which they don’t have to stand next to and explain. They should become so involved with the means that they have available to them, that they are capable of making a form (in this case, the painting) which is the exact expression of what it is they want to say.

Now, the difficulty is it presupposes an audience out there who is willing to make the effort to take the time to decode the image that was made to get at what is being expressed. It’s not as obviously straightforward as simply someone telling somebody else what they think or feel.

And pushing it one step further, I suppose the most intriguing thing about the whole process is that if it’s going to work—if painting or drawing, any of the traditional visual arts are going to continue to have the kind of impact that they had traditionally—they really to have to survive as functional languages. Their vocabulary, grammar and syntax have got to be used with complete confidence and (here comes that word, again) skill for whatever they’re going to be used to express to actually make any sense.

I don’t know whether that’s exactly what you were looking for in that question, but it’s something I think most painters today, given the plurality of the art world, probably have to think about. It seems that it is, at this point, a much smaller part of the overall way of making images than it was even when I started school.

LG: It’s hard to say. Everyone is going in so many different directions that it’s anyone’s guess where it will all end up.

HR: Yes, true, but it’s encouraging to see that there are still a lot of people out there who seem to be interested in learning how to paint and draw, and as long as that interest continues, I supposed there will be paintings and drawings to look at.

LG: I recently interviewed the painter, Julian Davis, who said: “In the dark ages, people were as likely to follow animal tracks as to use the empty Roman roads. The history of art is similarly full of amazing acts of forgetting, of losing mastery.”

This quote makes me think about the people who seem to want to reinvent the wheel, and then go riding off-track, bushwhacking it through the visual wilderness. I suppose sometimes this de-skilling can work but more often than not, I find it less interesting than art which is part of the continuum of language from past art.

HR: I think it’s not even so much the past. I got into this initially because I really enjoyed looking at paintings. I mean, it’s no more complex than that. I still find them endlessly fascinating and rich if they’re well made. And there are a lot of other competing forms out there, right now, that I simply have far less interest in. I think that is such an entirely subjective phenomenon. People obviously are going to follow their interest in a direction that seems satisfying to them.

But for me, teaching for that long and making the paintings themselves is really about trying to, in the smallest degree anyway, add to the accumulation of this discipline that’s been going on for a considerable period of time, and make things that you would hope that at least a few people out there will also be interested in looking at.

LG: Thank you again for taking the time to make this interview, your words here will be of great interest to many painters.

TWO SLIDE PROJECTORS 2005 18X32 inches oil on canvas

Engine x 4, #1 – #4 2009 Oil on canvas each panel 6″ x 6″

Another great article. Particularly liked his comments on painting from direct observation vs. from a photograph.

Thank you Larry and Mr. Reddicliffe for this interview. I have spoken to Jerry Saltz about my work as a graduate student at the Art Institute of Chicago and can say that he is really as genuine as they come. His generosity and openness towards art and artists are at the heart of his criticism, a necessity for a regular newspaper or magazine contributor to succeed in our current art world. Sadly our current art world demands Jerry’s kind of open and generous attitude toward artistic expression, form and skill. I personally prefer the ideas found in the writings and lectures of Dave Hickey and Richard Shiff, which clarify relationships between institutions of art, artists and interpreters of art working today and challenge the definitions of postmodernism originated by Rosalind Krauss, Hal Foster and the like.

My dream is that visual art will one day function like music, where people trust their own taste and instincts, and they will buy art based on what gives them pleasure. I teach painting and drawing at the college level in Austin and can say with a happy heart that art students today are like garage band musicians – they seem to understand instinctively that there is a craft to drawing and painting that helps them to make what looks cool. It is this goal of making what “looks cool” that I see taking the place of institutionalized thinking about art as something elevating and educational.

Like Mr. Reddicliffe I became a painter because I love looking at and making paintings. Dennis

Adrian another teacher of mine at SAIC said that performance art was simply bad theater. It is not necessary in the art world to accept every artistic expression as valid in the name of pluralism, unless you are making your living writing regularly for art journals that require you to do so. I am personally so sick of the state of contemporary art that I literally cried at this years Whitney Biennial. Long live modern representational painting! God bless you Mr. Reddicliffe and you too Larry!

Sorry about getting on my soap box. Being from one of the most southern cities in the US, feeling rather isolated and ignored, I just long for the kind of paintings and painters interviewed in this blog. I wish we could all form some sort of artist’s compound somewhere where we could all live and work together.

god bless… noel

Thanks for your comment Noel. I find it difficult to form opinions about post-modern conceptual or “New-Genre” art as Harold Reddicliffe called it. Some of theses artists just seems prankster-idiotic or fashionably ironic hipster-kitch while other artists have something interesting to say in a novel or shocking manner. However, I don’t have any problem with calling any of this art, let them have won that battleground. If someone feels that something or some bizarre act is “art”, who am I to complain? I tend to think of it as more “fashion art” or ‘street-theatre art”. What I do object to is having painting considered the same thing. I would venture to say that the Whitney Biennal hasn’t been about Painting for quite some time. Let them have Art for the time being (as we have no choice about it anyway…) and put our efforts into continuing to make great Painting a vital force for our visual culture. A big part of the problem is that there is such limited education these days about what is involved in great painting that combined with the wide range of opinions about how to define what great painting is makes it even harder.

I can relate to your feelings, Noel, about isolation in the art deserts of the south-west. That is a big part of why I started this blog as well as my recent venture to Italy. However, when I hear the idea of an art compound, I think of Van Gogh’s pursuit of that venture – and how that all turned out when Gauguin moved in…

Once again, thanks.

Really great interview. I had never heard of Mr. Reddicliffe’s work, but that’s what makes this blog so awesome. It’s so encouraging and heartening to me that I can keep discovering artists that are thinking about and dealing with the same issues as me (the particularities of seeing, the difference between the camera lens and the eye, paint surface, etc,etc…) The whole idea of skill I was thinking about recently while watching the Olympics. I mean, one of the things that makes a gymnastic routine so beautiful, is that this person has spent years perfecting a set of moves that is extremely hard to do. I think one (and there are many more) of the things that makes a representational painting beautiful is that trying to paint what you see is hard to do; in other words, it is a very rigorous and hard-won skill. Thanks again…this is definitely worth another read.

Thanks for your comment Francis. I agree with your comment about skill but I also am finding my definition of what constitutes skill broadening considerably as I get older. However, painting from observation, especially outdoors, is what interests me most – not just because it’s difficult but because, if done well, it often seems more poetic, visceral, personal and honest than labored studio inventions. (I actually love both but…)

I second Noel’s frustrations. Being from Dallas myself, I was never exposed to a lot of these great contemporary realist painters in high school or even at my first university. It seemed like all the art professors I had just preached about the abstract expressionist or post modern art forms. Freedom of expression seemed to trump any of the harder work of really looking, drawing and making things “correct”. I felt lost and really uninspired by most of my professors until I transferred to LSU. Luckily I had a great professor from New York who had studied at the Studio School. She taught some very rigorous drawing and painting classes which most of the students hated. But I loved it. I finally felt like I had met someone who knew what the hell she was talking about and really enjoyed the hard work.

Anyway, I’m not quite as accomplished as most of you on this site, but this blog is right in my wheelhouse and has been like a continuing education for me. For that I am very thankful.

Thanks Jon, reading comments like yours encourages me by hearing my work for this blog is worth the trouble.

Great interview, Larry. Thanks for posting this. The work is amazing.

I love that you allow people to discuss your interviews Larry. This blog really makes me feel connected to a community that understands and appreciates the rigorous discipline and seriousness of contemporary figurative drawing and painting. The act of being quiet, focused, patient and intense while contemplating a live person, meaningful object or place – the conditioning and deepening of the act of seeing through our techniques and media – is the real reason why many of us draw and paint. This is why I personally have to work from life. To make a drawing or painting from reality is to fuse external and internal reality into an object that makes human subjectivity manifest. Realist paintings and drawings are primary objects that testify to being alive and conscious. Of course paintings by artists like Agnes Martin and Brice Marden do the same thing without subject matter, but to look at a realist painting made by a master like Antonio Lopez Garcia or Rackstraw Downes is to experience slow, careful and dedicated seeing. These artists capture the attention of people regardless of whether or not they have specialized training in the visual arts and give them as long a moment of connectedness and restful magic as they want, museum or gallery hours permitting. To sit in front of Marina Abramovi? at her retrospective performance at MoMA must have been wonderful for people who really understand her intentions, but that time and audience are fleeting and small compared to those of realist drawing and painting. Once a performance is over memory, photographs, video and concept are all that remain. A painting by Susan Jane Walp will calm people’s breathing and make them see that everything is going to be alright long into the future.

Great interview. What an interesting painter Mr. Reddicliffe is! I was merzmerized by his painstaking methodology, i.e., mixing 12-15 values of the same color on his palette. Knowing more about another artist’s process is not only intriguing, but makes appreciation of their work that much greater! I spent a great deal of time examining his work! Which brings me to my next point: I am now apparently able to deeply immerse myself in Painting Perceptions and not realize an entire evening has gone by! And this has happened on more than one occasion! Thank you, Larry!

Harold Reddicliffe was my drawing teacher my first year at BU in 1988. I think one of the important lessons he imparted was the importance of the gesture. I think you can see that in his work- Despite the meticulous surface and accuracy of the drawing, there is still a grace to his work that doesn’t feel stiff. A great painter and educator- We all gave him mega respect. Thanks for the interview.

Reddicliffe’s work reminds me of the art and sketches from the brilliant movie, “Hugo” directed by Martin Scorsese. Thank you for this interview & insight into his work.

I thought this was an interesting article. But to me it strains credulity that he draws these precision objects from life. he may paint them from life, but the drawing itself would have to be so intricate and time consuming that he would only be able to do a few a year.

why is it so hard to say, “yeah, i traced that”?

James, I can assure you that Harold Reddicliff doesn’t trace a projected image. The interview goes into his drawing and painting process at length. I suspect your problem is that your mind hasn’t yet experienced enough masterful painting and drawing of this type so your mind “strains credulity” rather hastily. He does indeed spend much time on these paintings, a fact you would get from reading the article.

Hi James,

You might indeed think the drawing was traced from a photo. However, I don’t actually think it would help much if at all. For one, tracing detailed images onto a canvas is actually pretty difficult. Also, the composition is really important, and by working his way, he’s able to compose directly on the canvas.

You can see from this step-by-step that he uses drawing tools like straight edges and compasses to help achieve the geometric precision.

http://www.artistsnetwork.com/articles/art-demos-techniques/detailed-drawing-demo-harold-reddicliffe

And here’s a good article about Reddicliffe’s work: http://dcommon.bu.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2144/1394/Reddicliffe_Catalog.pdf?sequence=1

And another one with the step-by-step: http://www.hirschlandadler.com/MEDIA/06459.pdf

It’s just odd to me that the rise of such detailed renderings since 1850 or so coincides with the rise of photography…its use by eakins, sargent, sorolla, repin, etc is self evident– and those were gifted painters. But none of the early dutch still-life or early trompe l’oeil painters were able to achieve such verisimilitude as we are able to do now. This is not because our artists are so more gifted today– but rather that they are able to use photographic references as an aid. (the one guy we look to for that, Vermeer, is strongly suspected to have used optical aids…

I did read the article above and I am simply arguing that I think this artist traces these images. The evidence Mark helpfully provides doesn’t show that process in detail (it reminds me of this, in fact… http://imgur.com/LU93H) So we’re left with taking the artist at his word. As an artist myself, i just don’t believe him. The evidence is in the paintings of the fan– where theyre all the exact same proportions. Getting the fan correct once is a task, but three (or more times relative to one another?) that alone would take weeks if not longer (assuming teaching duties, meals, sleep, etc). If he spends twice as much time on the paintings as the drawings, we’re talking months of activity for a single painting or two. not much time to build such a portfolio. Moreover, why Wouldn’t you photograph and trace? What about this process requires that step to be some sort of contemplative or meditative process? it’s production– be efficient! And, yes, you can totally trace onto canvas. tons of artists do. and tracing a photograph doesnt mean you can’t monkey with the composition later… im just skeptical of all of this…

anyway, thanks again for the article– this is a great site.

Hi James,

“But none of the early dutch still-life or early trompe l’oeil painters were able to achieve such verisimilitude as we are able to do now. ”

Really? http://emptyeasel.com/2007/03/28/willem-kalf-dutch-master-of-still-life-paintings/

We could go back and forth about the tracing issue forever, so let’s ask Larry to shoot Harold an email asking him about it…

By the way, I’d love to check out the results you got with tracing- Here’s one of mine: http://www.markheng.com/images/HarvardTwilight.jpg

I’m not 100% crazy about the results, but it was a long time ago, so I mark it up as education.

James, there used to be a number of people who believed the Apollo moon landing was a hoax, today there are many people who feel the same way about global warming.

I know Harold Reddicliffe personally and can tell you with complete assurance that he is the real deal. He is a respected professor (retired) at Boston University and shows in the one of the worlds leading galleries for realist art of this type. Your comment about efficiency vs a meditative process clearly demonstrates that your confusion about the nature of creating fine art. To basically accuse him of lying is outrageous. However, I cut you some slack as you don’t sound malicious in intent – just someone who doesn’t yet know much about this sort of painting.

I’m generally less interested in paintings where main purpose is to copy the photo. There are many photo-realists who do this and I find many of their works quite boring. That said, I’m sure their are some painters who use tracing with creative and interesting results, I believe most any approach can be made valid in the right hands, I’m not a purist. However, tracing can be a fairly inaccurate means of speeding up the mapping out the edges of forms as seen by a photo. The real work and artistry is in painting the light, the space, the forms and their relationships between each other and of course the creative thoughts behind the reason for making the painting to begin with. There are no “tricks” to making truly great paintings.

Larry– feel free not to post this rant as I’m probably just wasting everyone’s time here.

I’m not calling Prof Reddicliffe a liar. I just think he wasn’t being fully candid about his process. If you say he never traces, then fine–I’ll drop it. But I’m not sure why you wouldn’t project an image– it would save so much time. You can still make all the creative adjustments you need in later stages. This isn’t akin to being a moon-landing denier. A LOT of Great Artists have used photographic aids going back for 150 years. It’s not unreasonable to suspect something similar here–hell, he even paints projectors!! I also don’t think it’s impossible to make those initial drawings without photos. it’s just really time-consuming. Similarly, you can make your own paints and boil your own rabbit skin glue– but why waste the effort? lastly, i don’t think he’s copying photographs at all. his paintings do not look overly photorealistic– it’s clear he paints from life to me. And they definitely have a great deal of artistic merit. This was just a comment about his initial process.

I feel like we’re living in the steroid era. Leaving aside the illegality or cheating, i think it’s pretty analogous. People today are using technology to their advantage, but often feel it’s something to be ashamed of and to conceal–especially with painting (and sometimes photography, what with the advent of photoshop). Lay-people are often unaware of the process (due to crappy art education at all levels) and therefore jump to the conclusion that today’s draftspeople are more highly skilled than those of years before. e.g., “wow, that’s amazing– it looks just like a photo”–in the same way many people think Barry Bonds > Willie Mays. when artists are not candid about their process, it adds to that myth. That’s why i was raising the question earlier. If I was unfair or slanderous, then I apologize. I just wish more artists/instructors were like Eakins, and publicly embraced photography as a legitimate aid. It’s almost like everyone’s gone into the closet.

Mark:

Thanks for your comment. I loved your painting– it was a great effort. Incidentally, I live about a mile from Harvard Square. Your link to Kalf makes my point, though. His paintings are highly realistic… but not photorealistic. Look at estes or richter or someone like this clown: http://whatanart.com/2011/09/28/photorealistic-still-life-paintings-jason-de-graaf/

and you’ll see what i mean. My point is that strictly as a draftsman, it’s obvious that Kalf is much superior to any of those photorealists. But your average person may not realize that. Again, this is not to say photorealism is without merit (at least for richter and estes)… but it’s not evidence of great draftsmanship, either. Sometimes it’s an indicator of the opposite (e.g., Richter says he can’t draw worth a flip)….

Anyway, sorry to come across as a jerk. I really like Reddicliffe’s work– and David Campbell’s on the front page today as well. All the best.

James, thank you for clarifying your previous comment. What your are saying now makes more sense to me. I don’t know if Prof Reddicliffe has ever traced – I’m sure he’s likely to have at least tried it at least once – and found it didn’t serve his needs. In the interview he said he didn’t grid photos, use projectors or even use a viewfinder with more than the one center horizontal and vertical division. He explains why in the interview. To me that is pretty clear and for you to question if he’s being fully candid – does come rather close to saying he is misrepresenting his process somehow, which to my mind is a “nicey-nice” way of saying he’s lying. But you do offer several reasonable points and make a good case for your position on the matter. I’m sure Prof. Reddicliffe can handle any questioning such as yours.

But for you to then say “But I’m not sure why you wouldn’t project an image– it would save so much time.” you raise a whole other concern; which is what is important to you. You are apparently concerned with saving time “it’s production, be efficient” Not all artists feel this way. Some painters, like Antonio Lopez Garcia, will spend years on one painting. Painters like Euan Uglow spent countless sessions with getting precise measurements done in what may seem like a labored idiosyncratic manner – but the initial drawing becomes an essential reason for making and even the subject of the painting. What I think you may not be clear about is that to Harold Reddicliffe – this manner of drawing is fun, engaging and essential to his needs for the painting and for his particular way of being in the world.

One last thing about tracing. I think you’re right that some artists aren’t candid with their process or outright lie and cheat – such as trying to pass off computer reproductions as hand-made art and the like. The public is often indifferent and ignorant and the artworld all too often is more concerned about what can sell more than what has integrity and vision.

I personally feel that some painters who use projection can make great paintings as well as lousy ones. The trick is in the painter not the tool. It is true that many great painters used photographic sources and aids – many great paintings have been made this way and I have absolutely no problem with that. My point is simply to say that Prof. Reddicliffe doesn’t choose to use them.

That said, I tend to think that some painters who project paintings to speed up production can only do so effectively if they already can draw well from life. Painters who use projection as a shortcut to good drawing usually just make less interesting paintings (to put it nicely) However, I know of very competent painters, like some portrait artists, who will project photos to speed up the process of getting proportions, etc right – when indeed the goal is production and making the client happy. I’ve tried this myself a few years ago – when I was trying to figure out a way to make more money from commissioned paintings. I found projection to be technically problematic (various lens distortions and the like) and less useful than I imagined. When the goal has been to work quickly for a commissioned work – I’ve found it more useful to grid a photo and just map and manually transfer the very broad linear boundaries of the important elements of the image onto the canvas.

Additionally, I think part what Prof. Reddicliffe is concerned with is in exploring the monocular vs binocular vision of the eye vs. the camera; the difference between drawing what you see with one eye vs two, and having a carefully arrived at vantage point are all critical parts of his process that could not be addressed properly by projection. But all in all – it comes down to what he said that it’s just more fun this way. More often than not – this is at the heart of the matter to many great paintings and painters…

Hi Larry, thanks so much for your in depth interview with Prof. Reddicliffe. I actually stumbled upon it while searching for Morandi and am so glad I did. I have a particular interest because I was fortunate to have Mr. Reddicliffe as a Prof. in Columbus for drawing and painting. He may not know this but he was a major influence in my education at the time (1978-1982). I still feel the influence 30 years later. I went on to have a successful commercial art business (and still do). I feel I learned more about drawing, color, shape and design from Prof. Reddicliffe in my fine art classes than anywhere else. In a digital world, these skills are still valuable and useful to me.

As an aside, I scanned some of the other comments, although no defense is necessary, Prof. Reddicliffe always adhered to his described process and would occasionally show us slides of this process. And to the point there are ways to “do it quicker” seems to miss the point. From your interview I gathered it’s about process, about the experience of doing, the act and enjoyment of creating, not just “getting it done”.

I have a favor to ask Larry. If you happen to have contact with Prof. Reddicliffe, please pass on my thanks for his guidance, teaching me about Morandi, Dienbenkorn, Ingres, amoung other things. Frankly, I not sure he will even remember me, but please pass it on anyway if you would. I’m happy to say that I have recently taken up fine art painting again and enjoy it more than ever. Thanks again for taking the time to produce this interview.