I’m pleased to present this interview with painter Grant Drumheller where he talks about his background, work, process and thoughts on painting. There will be a solo exhibition at the Prince Street Gallery in NYC December 1 – 29, 2016. The Prince Street Gallery exhibition catalog has an essay by the poet Charles Simic who states:

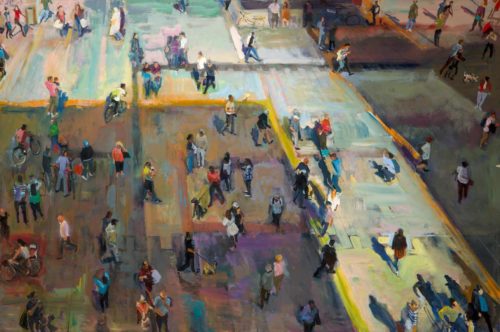

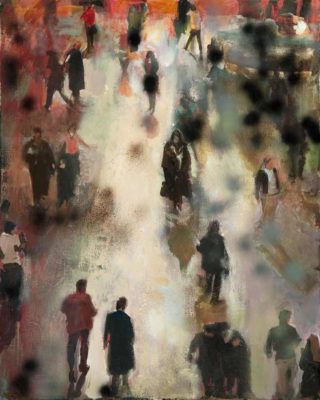

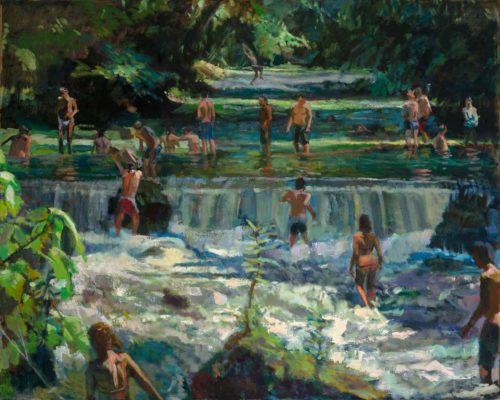

“…He is both deeply engaged with what’s in front of him and well-versed in the history of art. Breughel’s paintings with their multiple scenes taking place concurrently in the same painting come to mind, although Drumheller’s is closer to French Impressionists in his use of color. I have in mind their landscapes and urban scenes veiled in mist and fog where some familiar sight is transformed by the weather and endowed with strangeness and mystery. Like the French, he wants to convey the mood such images evoke in the viewer as much as he wants to show what is out there. The drama of these paintings is how the chaos inherent in such crowd scenes and the unity required to fix the overall image in our minds battle one another and then come together. It’s the vast visual repertoire at Drumheller’s disposal that make this operation possible, from his cartoonist’s knack of capturing with a few strokes the identity of someone in the crowd, to the many subtle and startling ways he employs color and the sheer joy and abandon with which he wields his brush that bring his paintings to life. It’s like watching a juggling act in which the juggler keeps us in suspense by keeping in the air more balls than it seems possible, but however it’s done, by magic or just plain hard work, what matters the most is that we can’t stop looking.” – Charles Simic

Drumheller is a professor at the University of New Hampshire where he has taught since 1986. He was a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome in 2009. Drumheller has shown widely including one person shows at the Currier Museum of Art (Manchester, NH) the Creiger-Dane Gallery (Boston, MA), and the Grace Institute (New York, NY). His work is represented by the Greenhut Galleries, Portland, ME, the George Marshall Store Gallery, York Harbor, ME, and the Prince Street Gallery, New York, NY. He lives in New Castle, New Hampshire with his wife, Karina.

Larry Groff: What led you to decide to be a painter?

Grant Drumheller: I was the kid who was a good artist and ended up going to art classes as a youngster. I had a great art teacher in high school but it wasn’t until I spent a year at NYU as a liberal arts student that I knew I had to be in art school- and transferred because someone said BU had a good art program. When you are 19 you follow advice, literally. I was challenged and worked very hard – a few of us would spend all weekend working on the projects. We’d camp in the studios. During my third year painting class I had what I could only call “a painting experience”- a moment of forgetting, complete immersion, of falling into the work. I liken it to what actors say, “God was there” when it feels like something moved through you. I was hooked then.

LG: The BU painting department is noted for its traditional approaches to drawing and painting in the undergraduate studies. Reed Kay was one of your professors and also Philip Guston and James Weeks. They were all very different painters but their combination must have been very inspiring. What can you tell us about what school was like for you back then?

GD: How fortunate I was to be a student there! I was made to draw 9 hours a week for four years- from life! In addition we drew in all the classes, with clay, or paint! We were not told we were trying to make art. That was going to come down the pike. I accepted that if anything worthwhile would come out of me, it might take more than 4 years of tuition and time. I admired and respected the students and the teachers were awesome artists. I learned the figure. Of the painters you mention, Reed is the only one who survives. I try to see him fairly regularly. He is one of the most articulate artists and thinkers- his stories are great and I like to hear his opinion about everything. When my daughter Tess- who he has known since infancy and followed her studies at Barnard- went into the wine business, I called to tell Reed. She was dealing a small vintage biodynamic portfolio and he didn’t skip a beat…”Great! It’s about QUALITY! Wonderful!” he exclaimed. He provides me with a lifescript- still teaching me.

LG: Reed Kay wrote a book back in 1965 The Painter’s Companion I haven’t read it but I’m curious if you know it and think it still useful?

GD: The book remains very useful- I use his recipes to this day for glue gesso and other things. You should know that I spent my first year of teaching replacing him for the Technical Painting course while he was on sabbatical. It was trial by fire. I had taught a few Beginning Drawing Courses around the area but this was a lecture and demonstration course. I remember I thought I could read his ring binder of personal outlines for the course. I quickly found out I had to write my lectures longhand beginning the Wednesday before for the following Monday class- and rehearse the demonstration of the techniques! Grinding oils, making pastels, all of it! I even introduced a portable fresco painting project to the curriculum so students could feel the experience of working on wet plaster- something new! I had my own assistant but even so, it took a lot of effort! I had been Reed’s student, then assisted him as a graduate student in the class. Nevertheless, I needed my own level of preparation. When you teach you have to really learn it well, and for me it meant to learn it anew.

LG: Reed Kay must have had some interesting stories.

GD: Reed’s stories are often about the past and I love listening to them. Recently, I had lunch with him and asked him about Edwin Dickinson. He recounted a few gems. When Dickinson came to BU to give a lecture, he didn’t show slides or talk about his work, rather he spoke about the “custodianship of the palette”. The Dean of the College had sat next to Reed and leaned over and whispered, “For $500, this is all we get?”

Reed recounted the time when they were teaching at Skowhegan, Reed would see Dickinson standing knee deep in the lake, scrubbing his socks. “No one has to wash MY laundry!” Dickinson would exclaim.

My favorite Dickinson story was from the same summer when he was being asked questions during an evening gathering. Someone in the audience was trying to goad him to comment about abstract painters on ascent in New York at the time. According to Reed, he didn’t take the bait and said, rather, “Art is a great lady, and she can take care of herself”. I thought that was beautiful.

LG: Please continue telling us about your experience at BU.

GD: The teachers there were from a very intellectual generation, and the combination of their dedication and all I had to learn and the MFA, Gardner and Fogg Museums made those student days quite intoxicating!

The graduate program operated completely separately. I had known Jim Weeks from classes and Guston was anticipated as a monthly occurrence. I was just expected to work. It was great because for the previous four years, I was pushed down, compressed- like a spring. I was ready to be released in my work! The first year was a struggle- I painted two frankly derivative paintings, but Guston was indulgent. “If you were doing this in 10 years, I’d be worried, but not at this point.” Of course he spoke from experience, his early work having been influenced by Ben Shahn and Picasso- and I was young! You have to look like someone at the beginning, The following summer and year were filled with painting, with Guston egging me on. I really painted for him.

LG: I understand you were the student Philip Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer writes about in the below excerpt from her book Night Studio. A Memoir of Philip Guston. She touches on some very interesting point here and I’m curious about what you can say about this?

“One day,” another student wrote, “while Philip was looking over some of my work, I confided my feelings of hopelessness at my future as a painter. Philip quoted a line from one of Kafka’s diaries, which I carry in my spirit and mind to this day. When he saw how despondent I’d become, he told me that Kafka had written, ‘Art is the axe that breaks the frozen sea within us.’ I sort of stood there, speechless (he always seemed to have a great flair for the dramatic word). I thought that just about summed up in ten words what I’d been feeling for the past 23 years.”

“It feels like I am a child, struggling with a sentence only half said—faced with never being able to finish that sentence to the one person who matters.” The student who wrote this note also sent my mother an opening announcement for his first one-man show in New York four years later, in 1984. “Philip remains the most inspiring of my teachers,” he wrote then, “in his commitment to painting and as a role model in his self-trust and courage. It saddens me that I can’t share my enthusiasm with him…. The day I won a Fulbright to Italy, I ran up to B.U.’s office and found Philip. His reaction was revealing as well as endearing. Philip’s face lit up with his crooked grin and high eyebrows. He then gently patted my cheek with his hand. I expect I’ll remember Philip’s visits to my studio for a long time, but his tenderness and warmth at my ‘success’ is my most vivid memory.”

During the difficult times of the 1970s, when the art world was still busy being shocked and offended by my father’s late, figurative work, his shows at the David McKee Gallery were always well attended by young painters and painting students. After the long-standing disappointment of no sales and negative reviews—which persisted for a decade, until shortly before his death—it was heartening for him to see the interest of the younger generation in these strange new images.

Some powerful force had moved through him, he often told these young painters. That was how he had come to see it in those last years. My father refused to claim ownership of this force; he approached it with great humility and trepidation. What he had learned by the end of his life was how to position himself, he told his students, how to make of himself a vessel for what moved through him. “I never feel myself to be more than a trusting accomplice,” he said.

GD: Well that is a big quote. The young guy getting the pat on the cheek is me. I remember Guston’s comment that “art is the axe that breaks the frozen sea within us”. But Mayer’s comments in the third passage intrigue me the most. Phillip was an extremely well read man and loved modern literature- Kafka, Eliot, and Samuel Beckett among others. He was a talker and a brooder. Those late “overcoat” paintings and book paintings all reference Beckett.

Guston spoke poetically about the paradoxical mysteries of painting, about “doing it”. The Clark Coolidge book recreates those conversations beautifully. He suggested that being “a vessel for something moving through him” was something I could try to find as well. It was the state of doing I aspired to- I knew that I would do whatever it took to feel what I felt in third year painting again! Guston spoke about the Sung Painters who he admired, “do something a thousand times until someone else does and the rhythm moves through you…”. As my friend George Lloyd said, “This is a fragile thing we do” and he is right. A painter can grind to a stop without much effort. Every idea seems stale and a cliché- and let’s face it, being a painter can be tedious if it isn’t engaging and going well. The trudge in between the moments of sparkle can drive one slightly insane. I tell my students to get used to spending a lot of time alone in a room. Guston encouraged and gave license for us to explore our instincts and work in spontaneous and improvisational ways. We graduate students were like the hooded figures in his paintings- hoodlums driving ourselves to the edge of town- outlaws dispatched with a mission. He was trying to direct us to the areas in our paintings that were “plastic”- which in its barest sense means to be alive- looking for the heartbeat in the paint. I also think he meant where the space breaks when the paint makes form/space. So in a sense I accomplished having those painting moments while painting in graduate school. I ended the year by getting a Fulbright grant to paint and live in Italy.

That time of forgetting while painting does not happen all the time, but more frequently than it used to. When you get out of the way of yourself while working, so to speak, something else can happen.

It was the “third hand” that Guston talked about. To help us get there, he had a few tricks he’d give us like, “When you want to reach for a green, pick up red” and he told us to put the palette right under the painting- none of this off to the side stuff- keep the palette right under the work. These were ways to trigger you, and make the work unexpected. He didn’t especially prize consciously clunky work, as one might think. I find the painters today influenced by him are mostly missing the mark- looking like or borrowing affectations does not mean anything. As the quote suggests, the work moved through him and was not an attitude or style- it was life and death.

The worst thing Guston would call something was “Waxworks”- a painting that was DOA.

LG: Working from observation must have been an important early part of your training. Today, I’ve read much of your work is more about painting from memory and invention, especially your crowd paintings. Is observation still something important for you today?

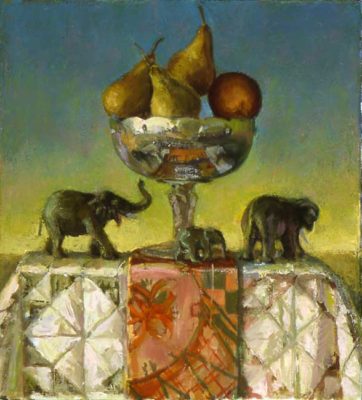

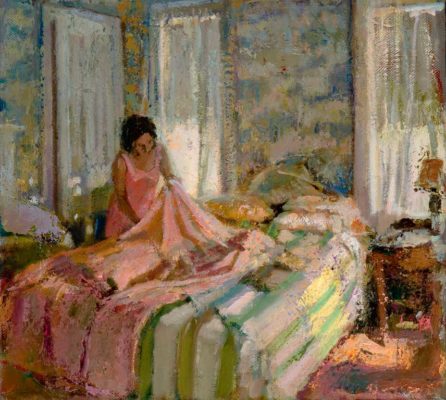

GD: Absolutely, it is terra firma. I still work from life. I paint heads and still lifes when I am stuck. I teach working from the motif- being sensitive to relative color and value relationships- the mixing of color and how value, temperature and intensity position the elements. I teach drawing- not copying but understanding the structure underneath. So a heightened awareness is what I teach. Repetition is also important and has a kind of active meditativeness.

The work in the show relies on my sense of seeing, of observing these experiences that I patch together. If I want the figures to move differently or be more foreshortened then I am capable of conceptualizing the space. If things seem pat or even, I erase the thing and try again. Some pictures are impossibly difficult and go through generations of changes, and others come right out of me. I pay a lot of attention to the negatives, the reserve spaces being worked around the figures, the color corrections, erasures, and stitching back together of a color against another color. The figures moving over a surface gives me an armature for improvising the image. I utilize the skills learned in observational painting and drawing. Perhaps the rule I would suggest is that “the way one sees it, might not be the way it should be”- and go forth with that in mind. I also rely on my own documentary evidence, photos and videos- but try to hide that stuff from myself, to not rely entirely on it.

LG: What is the importance of drawing to your work? Do you make a lot of drawing independent to your paintings?

GD: I don’t think that I draw much, but then I realize I have a lot of small things lying around. They are not pieces that I would necessarily show but they represent a part of the process. While a graduate student, one self-imposed goal was to try to develop for myself a “working method”, a series of steps supporting an idea and culminating in the painting. These stages started with raw drawings- like the early sketches Picasso would do, just small sketches invoking the broad ideas and the big directions of a composition. Then I might try a small color painted sketch and then launch into the big painting. I have changed that now, not so programmed as that.

I can feel a lull coming in my painting – it might be soon or in a few years, and I am looking forward to that time when I can put down my brush for a period of time and just draw. I already have the papers and the ink.

LG: How do you go about starting a painting?

GD: I will have a vague idea and wait, just hold the idea, turning it in my mind until it builds to a point where I have to begin the painting. It can begin by something as simple as a texture of paint leavings from the palette. Sometimes I will paint big shapes of arbitrary color. I have done this for a long time, and they are really pretty “pictures” at that point. I remember starting a painting and some collector walked in just then and wanted to buy it. Guston saw it too and said, “I could find 10 people to tell you that that is good, but it’s not”. I knew what he meant. The notion of making a painting is the farthest thing from my mind. I want a painting experience! Even when I am painting a small image, the beginning is a libation to the Gods. I really don’t like art, I want to feel the reality of an experience. I do not want to know what the painting will look like in the beginning so I am throwing myself off of too-strong-of-an-idea as much as I am beginning.

I wait until I can jump into the picture with all fours. It can sit for months with the “overture” on it. I am waiting for it to call to me. Often when I start a picture over, I will obliterate the painting underneath with a dark glaze of red or green- not related at all to a subject- or paint a live coat of pale color to work out of. Guston often worked on a wet wall of paint- a full-on surface of fresh titanium or titanium and lead white and started to draw. I usually work one painting at a time. I obsess with the demon on the easel.

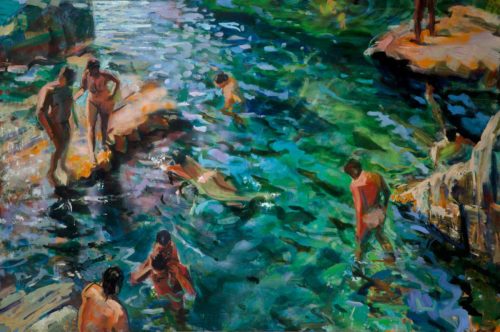

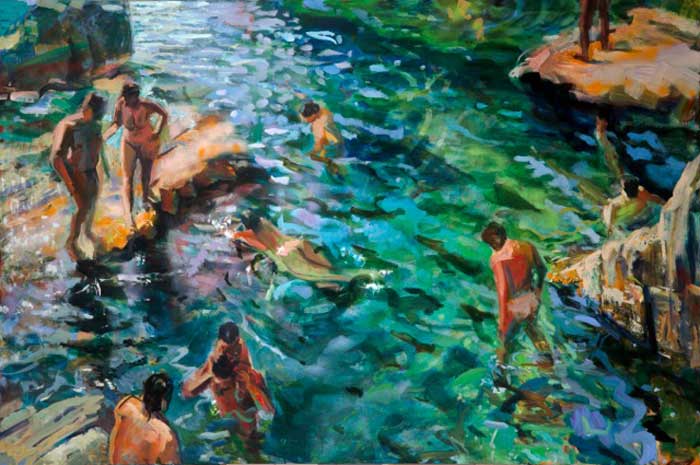

Some of my new work is with acrylics, a medium I used a lot 30 years ago and which I am back to now. I have several very large brushes and can make both giant strokes and small ones. It doesn’t match oil painting and I still do that in my home, but it has the benefit of dispatch. I also don’t feel very precious about anything I do with it. The strokes can “sit up” so it has a graphic look I don’t always like. I employ some spraying and a lot of rags in the process to make different transitions. I just gave a talk to some students recently and showed the progression of a picture over a period of about 8-12 months. It is in my current show (Rocky Cove), and the photos I showed illustrated the many dead ends and false turns it endured. What is there now was hard to uncover but in the end, the right one came to the surface.

click to advance slideshow of the five versions of Rocky Cove

I want them to look fresh and quick, a little on the “rare” side, and entirely intentional. Nothing is worse than a labored large painting. Usually there is a moment when the picture identifies itself, and it really should be painting itself. You just have to have your ears up and be on alert for it- oh and stay out of the way.

LG: Is it possible to talk about how particular gestures and the configurations of shapes and colors evolve in your work? Is there an improvisational element to your art making and if so what are some important ways you get the improvisation moving?

GD: The figures start in small clusters or one or two and I try to get one to hold the space it lands in. I often have the benefit of a pattern in the reserve so that it can help me see where it should be. If the passage seems dead I erase and try again. I wait for a scale of the figures to declare itself. I often do not know the ultimate zones of light and dark until the endpoint of the picture. So many aspects are in flux- I move the figures and if I am working inside a particular color or value- shadow space or light, it will have a bearing on the color.

LG: Please talk about how you go about putting your figures into the composition. Do you use a lot of studies, photographic or art reference or are these all done from memory and invention?

GD: I try to utilize my own photos and videos as much as possible. My lap top has around 10,000 photos on it not including the videos. I do pull images off the net if I am looking for something particular- like “dogs walking”- but I have a self-imposed rule to deviate several ways from the original. I would not welcome any accusations of plagiarism.

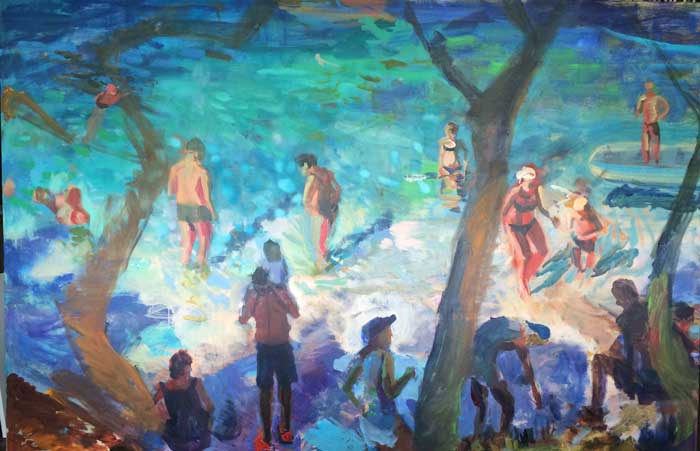

When I arrived in Munich, I focused on an easy access to a third to fifth floor window or terrace. The Paris pictures were from a trip intended for the purpose. So I do travel to places with accessible vantages. The beach paintings are harder and using a drone on a beach can be hard on the drone- people hate them! So I have to improvise more and take pictures from Maine and near where I live – and try to be discreet. When I first began this project I was in a hotel over the Piazza Minerva in Rome and would get up to take pictures at different times of night- often filming the action.

The difference with the photos and the reality is that the photos provide a gesture or a great and telling detail- a boot or a pair of sneakers, a big stride or a saunter that I can then riff upon. I take short hand notes with the paint and move on. I photograph the painting at intervals.

LG: Can you talk about the way you incorporate gestures in your art? Your paintings often depict large gatherings of random people moving in a public space as seen from above and far enough distance to diminish any clear narrative. Are you interested in suggesting an underlying story or are you mainly just working with the painting’s formal concerns about composition, color and space? What do you want to show with the relationships between the figures?

GD: Generally I want to show the arbitrary intermingling of many figures while passing through a space. The spaces are not about stationary action, and walking or pausing is a typical pose- so I will make up a little story about each figure, like characters in a play. I have pages of description in my head. The spaces are public and democratic- tourists, denizens, children, people walking dogs, older couples, younger couples, shoppers with bags, coming from the market. I even know their individual ethnicities, and the partially visible ones as well- the subtext for all of them. I know it sounds strange because the figures look barely there but somehow the fictions are inside me. It is like looking down on a crowd and letting your mind pass over each figure.

The gestures are intentionally without meaning or engineered, though the direction of someone walking draws an invisible line. The agora or public spaces in the rest of the world are often the only places that some people have to interact with others, and are by comparison rare in the US. I think they are a balm to the lonely. In Italy, where I visit and have lived, one frequently sees grandmas on bicycles riding through a crowd at midnight! In the US these spaces exist as destinations, such as Central Park in New York or Prospect Park and FT Greene in Brooklyn. You might see familiar faces, but a place you might encounter the same individual in passing over a period time is unusual. We have a small version of a public ground in Portsmouth, near where I live- Market Square.

LG: What helps you best decide that your painting is complete?

GD: Something happens, a breakage is the only way I can liken it. I find that if I want to get in and tune the colors or small relationships- I make myself pause because it is probably already there. Sometimes a large geometry will declare itself and a moment of particular light- that is an indicator to suspend work.

LG: >Has teaching helped the development of your painting grow?

GD: Well I drone about color endlessly, less so about “paint quality”- it seems so individual and personal to me. Since I have taught all my life I would find it hard to separate it out. I do know teaching is a good antidote to being in the studio- it has a performance aspect and the interactions can be very satisfying. I love young folk and of course, I revered and loved my teachers so it is a wonderful way to make a living.

LG: What ideas are most critical to get across to a student for their growth as an artist?

GD: Prepare yourself, learn how to draw, keep doing it. Develop a sensitive eye and heart. Learn to be present. Look for paintings everywhere!

And don’t think too much- that doesn’t mean not to be smart or knowledgeable- just keep moving. Try not to second-guess yourself. Read a lot, subscribe to the newspaper, be informed and know about the culture. Start a new picture after one has ended. Be disciplined about work and cultivate it.

Learn to support your habit- generally painters are great at something else. I would have been a pretty good chef- and like to think that I could have done any number of things other than teach. Teaching is especially well suited to being a painter.

LG: How difficult is it today for a student to find a university art program that still promotes studio-based, traditional figurative art training? For many years now the trend seems to be in placing more emphasis on the theoretical; learning what art is about rather than how to make it. What are your thoughts on this?

GD: I am sure that I have answered this by implication. My education was to prepare to work on a subliminal level, by instincts and gut driven. I think conceptual art is fine but in the end I don’t care about it. I am sorry about the descent of skill-based training and the results are disastrous for the art of painting. I think wrestling with painting is hard for curators, and besides, the art world can be ironically clever in the face of uncontrollable societal injustices. I think the expectation to comment on current affairs is hard to accommodate for most painters- at least in their own work. Perhaps as contrast, I am reminded of the Lawrence Wechsler article, “Vermeer in Bosnia”, initially published in the New Yorker, where he refers to Vermeer painting his quiet contemplative interiors while the reign of hell of the Thirty Years war was teeming outside his door. His art was an art of rebellion!

LG: What advice might you give a young painter in terms of surviving as a painter in today’s art world?

GD: Don’t expect a lot right away. Try to keep painting. The making of work is where to find fulfillment.

I heard Farrell Brickhouse talk about the community of artists he is part of by dint of living and working around Brooklyn. He spoke reverentially and I think he’s right. It helps to encourage community. Go to friends’ openings- turn up when the call is out, support one another. Artists are your most important audience.

From Grant Drumheller’s website

Grant Drumheller has been the recipient of a Fulbright-Hays Grant in Painting to Italy. He has also been the recipient of a Blanche Colman Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Artist’s Fellowship, a New England Foundation for the Arts Grant and a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Most recently he was a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome in 2009.

Drumheller has been a professor at the University of New Hampshire since 1986. Other teaching and speaking engagements have been at Boston University, Dartmouth College, Amherst College, the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley College, Maine College of Art, Monserrat College of Art, and Gordon College. He has taught for several summers at the UNH in Italy Program in Ascoli Piceno, Le Marche and at Art New England Workshops at Bennington College.

Drumheller has had numerous exhibitions, including one person shows at the Galleria Inquadratura (Florence, Italy), the Currier Museum of Art (Manchester, NH) the Creiger-Dane Gallery (Boston, MA), the Grace Institute (New York, NY), The Prince Street Gallery (New York, NY), Boston University, Amherst College, and Gordon College. His work is represented by the Greenhut Galleries, Portland, ME, the George Marshall Store Gallery, York Harbor, ME, and the Prince Street Gallery, New York, NY. He lives in New Castle, New Hampshire with his wife, Karina.

Great interview with a great painter. Not a bad story teller himself.

an aware draughtsman of light.and form….he’s right about ice, the good thing being that it splinters when you hit it, the fragments being the important bits………….

…..