I was fortunate to talk with Gina Werfel recently over Skype and interview her where she lives in Davis, near Sacramento,CA. I’ve long been enchanted by her paintings and was excited to get a chance to talk about her life as a painter and her concerns involving moving from being an outdoor landscape painter for many years to her current studio based abstract painting.

The writer Dewitt Cheng reviewed her 2012 show at the Alex Bult Gallery saying:

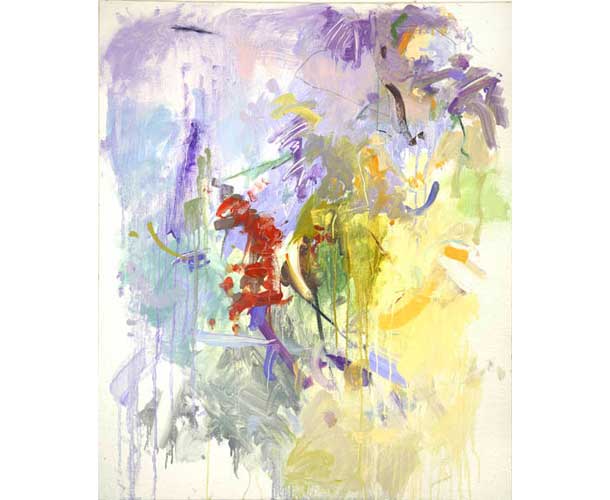

“Gina Werfel, a New York painter relocated to the rural Sacramento area to teach at UC Davis, has changed in recent years from making plein-air landscapes to exploring abstract, ambiguous fields of colored plasma, “fragments floating in a fluid space.” In the new abstractions, Werfel synthesizes shapes and colors remembered from her earlier work, motifs from daily life (including the studio), and the pentimenti, i.e., repentances, “the ghosts of previous decisions,” that accrue during painting and repainting.” “…Werfel’s new abstractions may have abandoned the window on the world for subjectivity and improvisation, but a feeling of landscape lingers in her “organic” palette and the forms evoked by her linear accents.”

I would like to again thank Gina for taking the time to speak with me at length about her work and concerns as an artist.

Gina Werfel has shown widely including the Adler and Co Gallery, San Francisco, Prince Street Gallery, New York, NY, Alex Bult Gallery, Sacramento, CA, Jane Deering Gallery, Santa Barbara, CA and many others. She is a Professor of Art at the University of California-Davis, Davis, CA

Larry Groff: What were some of your most important early influences that lead you to decide to be a painter?

Gina Werfel: I had always been interested in art growing up, every free minute I had was spent drawing or painting. My father died when I was very young and my mother, who never finished college, raised me. She too was interested in art as a child but her mother wouldn’t let her go to Pratt, which was her life’s dream. My mother was very supportive of me in pursuing my interest in art.

I grew up on Long Island where a family friend, a graphic designer with his own business, encouraged me to make art. I became very close to the painter Eli Friedensohn at Kirkland College (now incorporated with Hamilton College). He became a role model for me of a life as a painter.

I decided to design my own semester abroad in Italy with the help of Eli, who had received a Fulbright in Italy. The following summer, I went to the Boston University Summer Program at Tanglewood where I met Jim Weeks, a Bay Area figurative painter. These intersections with important artists helped me formulate my life as a painter. Elias Friedensohn also suggested I attend the New York Studio School (NYSS).

I started out at the NYSS studying with Gretna Campbell, Leland Bell and Esteban Vicente. Gretna was very supportive but I connected more with Mercedes Matter and transferred to her drawing class. Mercedes was one in a series of pivotal mentors. I had found my community of peers. This was what I wanted to do, to be around other artists, look at great art, to live and breathe painting and drawing.

LG: What in particular have you’ve learned from them that has the most relevance to your current work?

GW: Leland Bell taught me to look for color in the most neutral tonal situations, such as painting from the model. Mercedes was my main inspiration, teaching me about spatial connections and how to move from figuration to abstraction. Andrew Forge introduced me to British painters and a more conceptual approach to making art. I always remembered his quote from Degas, “Painting is not an outdoor sport” when I was feeling limited by plein-air painting.

LG: You helped run The NYSS summer program in Paris, how did that come about?

GW: Mercedes Matter had a reputation of ignoring women. I had a very different experience, she was an amazing presence for me. Her spirit of not saying no to anything was similar to mine. I remember painting late one night in spring of 1974 and getting together with Mercedes for a late dinner. The Studio School then had a Paris summer program and I asked Mercedes” Why don’t you let us run the Studio School in Paris this summer?” I was 23 at the time and I had just started dating my future husband. She said, “Great idea!” She paid for my airfare and we found a cheap place to live and we ran the program for two summers. Elaine de Kooning was there as well as George Spaventa, Nick Carone and Wayne Thiebaud. We also took the students out to meet Joan Mitchell at her home near Giverny.

LG: Did you have Louis Finkelstein as a teacher at the NYSS back then?

GW: Louis Finkelstein was an influence on me as well. Mercedes would bring him in occasionally. He once did a close reading of the philosopher Albert North Whitehead’s Process and Reality and because it was such a dense book there were maybe four of us who are brave enough to read it together just a few pages once a week sitting on the library floor with Louis. It’s interesting, after I left the school, Louis and Gretna became bigger influences on me.

During those two summers at the Studio School in Paris is when I started painting outdoors. I was also influenced at that time by my future husband, Hearne Pardee, who introduced me to plein-air painting. Once landscape painting became a big part of my practice, that’s when Gretna and Louis became more important to me. One of the things that wasn’t that clear to me while at the Studio School was how perceptual painting and drawing could ultimately lead to abstraction in my own work. I think what I admired in Louis’ paintings was that he worked in a place between representation and abstraction. Louis was also important to me because of his intellectual interests. The dense analysis that Louis brought to the Studio School was very important to me.

Another significant influence was Andrew Forge, who became the Dean while I was still at the NYSS. Andrew published a lot as a scholar and critic but was a very committed painter. He was very different from anyone else at the school; he talked about a whole host of British artists that I had never heard of before, like Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. He had studied with William Coldstream I believe. His was a more intellectual approach to painting than I have been used to at the Studio School.

LG: I don’t know if we hear as much about Louis and Gretna in the art world these days.

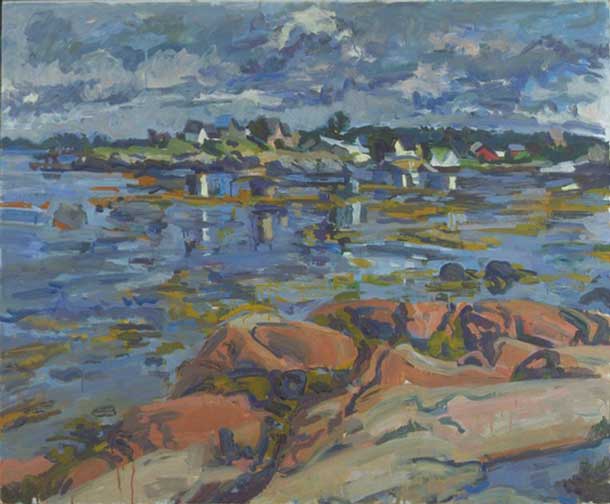

GW: It’s too bad they’re not better known. I think Gretna still has a following and Tibor de Nagy Gallery represents her estate. We rented their place on Cranberry Island in Maine for a summer. It was great to paint where Gretna had painted for so many years.

LG: You painted the landscape from observation for many years. Can you tell us something about that and how you’ve changed after moving to California and since 2008 have concentrated on painting abstractly?

GW: Back in the late seventies I got a grant for a residency at the Bear Mountain State Park. Alan Gussow, a painter, had set up an artist-in-residence program in the National Park System called the “Artist in the Environment”. For Bear Mountain, he chose 5 artists whose practices were quite diverse but we were all using the natural world as a resource–Melissa Meyer, Ned Smyth, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Rachel Bas-Cohain, David Grubb. David and I were the only observational painters. I had been feeling frustrated with painting the city, where the architectural forms seemed to inhibit my brush marks and gesture. I thought going to Bear Mountain would offer great views but it was totally green and enclosed. I started hiking into the woods to paint rocky stream beds in which I started to lose the horizon line. A few years later, when I interviewed for a teaching job at Vassar, an art historian said “Oh, Lennart Anderson calls you the woods painter”. Lennart was struck that I didn’t have a horizon in my woods paintings.

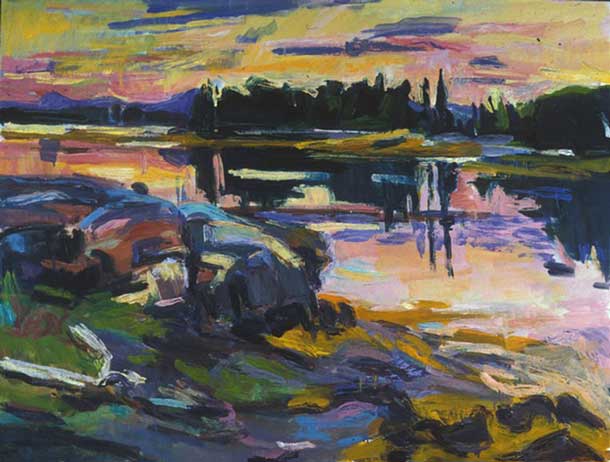

The location of my teaching jobs has influenced the kinds of landscape that I paint. While we were still in New York I was obsessed with painting in the woods, whether it was right across the river in New Jersey or hiking in Bear Mountain. When we moved to Maine I thought there would be tons of woods motifs, but there were none. Paper companies owned all the woods and much of my surroundings was young growth. I begin painting traditional landscapes but then every summer I started going out to paint on different islands. I realized that I didn’t like bright sunny weather; I wanted a kind of unity that comes with grey light and/or fog.

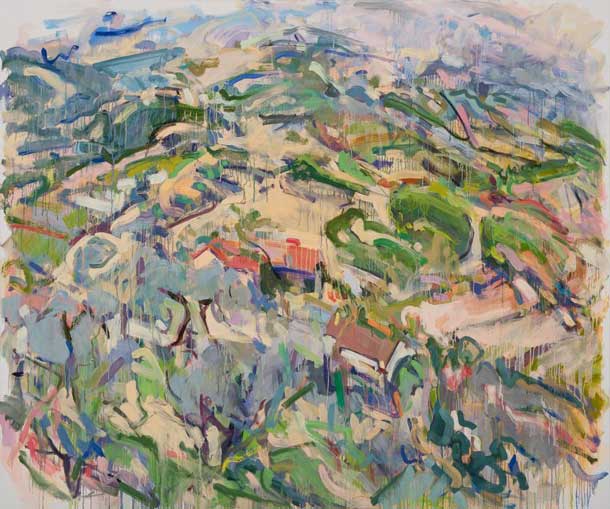

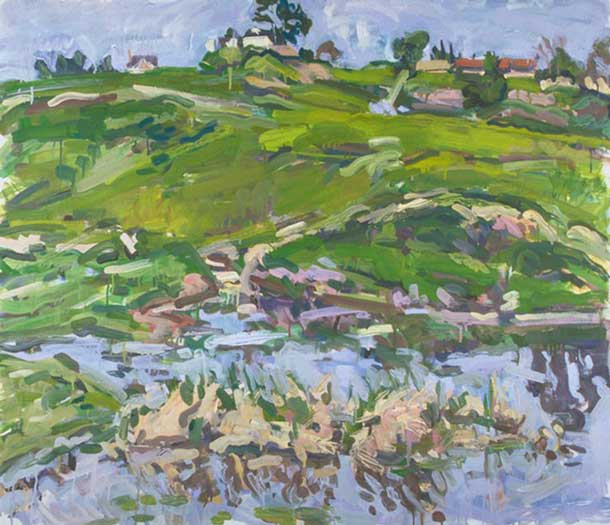

Throughout my four moves for teaching positions, water became more important to me. My growing up in Long Island as well as living in Maine made the ocean a very important subject, with my paintings incorporating tidal shifts and weather patterns. When I was recruited to Virginia and later to Connecticut where both places tended to be very overgrown, I painted still water ponds. After being recruited to teach here at the University of California at Davis I thought I could finally get back to painting water and hilly scenes again but once I arrived here I was shocked by how flat everything is, Kansas flat! I became very uncertain about what to paint. Eventually, I found the bald hills near Vacaville, where I painted for the next five years.

LG: Really I’ve thought the area around UC Davis was like what we see in Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings of the Sacramento River Valley.

GW: It is like that but he’s painting them from an overhead perspective. Anyway, for the next five years I would commute out to these hills, especially when they turned yellow – I loved them. Californians would always suggest that since I was a landscape painter I should paint these hills when they’re green! I’d tell them I hate green, I don’t want to paint green hills.

Since I was Department Chair and had young kids, I didn’t have the time to drive 45 minutes each way to my motif. I started painting locally at a dammed up stream where luxury homes were being built. One day I was painting a big house across the lake and I asked myself “Why was I painting this scene? This isn’t my life”. At that point I had only worked on my paintings outdoors. I hated this particular painting and decided to try something new. I brought the painting back to my studio and blew it up onto a large 48 by 60 canvas. It didn’t improve it. When I turned on its side, it started to look like an interesting abstract painting. So, that’s kind of how that transition happened. It was very exciting because some of the things I was always looking for in motifs, like when the wind would shift and break up the reflections in still water, I could accomplish in this kind of abstraction.

Besides freeing up the horizon line in the painting, moving into abstraction freed up my palette. I was enough of a realist painter that if the sky was grey I wasn’t going to paint it bright green. You asked me if I miss the stimulation from working outdoors. I do miss it, but I’m also figuring out how to incorporate observation, such as when I’m painting in my studio and I see a flood light that gives me an idea of a kind of mark I want to make or I just layer stuff that I perceive in different spaces into a single painting. I could never do that kind of layering when I was outdoors, except when painting reflections–where I could build up that kind of layering of space. I was putting up new images of my landscapes on my website a few weeks ago, they feel very different to me, but there was one I did a few years ago that is very close to what I do in my abstract work. Occasionally I might get an idea, like using an old doll to get a sense of a form I want to use, to layer that in. My source material is so much broader than when I was painting the landscape.

LG: Does your past involvement with observation-based landscape still play a role in your current work? Do you ever miss the structure of responding to observed situations and the excitement of painting outdoors or has the advantages of studio-based painting convinced you this is how you want to go forward with your work?

GW: When I am teaching on the French Riviera at Chateau La Napoule each summer, I still work outdoors as well as draw in museums in Paris from paintings and sculptures. I do still love the exhilaration of working outdoors, but it just may be that I am an outdoors person!

I don’t really feel like I’ve left observational painting behind as much as use it in a different way–collaged and improvisational. So I may start a painting based upon one of my son’s childhood drawings but then I turn the painting upside down to free it up from representation and then I’ll layer it with a segment of the view out of my studio window. I am constantly adding stuff from my everyday environment to free my mind from habitual ways of working- whether it is something incidentally observed like how my shoelaces are tied or the wires around my laptop or some flowers in a vase. The difference now is that I am not committed to one view of a motif but use perception as a tool to drive the work in new ways.

LG: What about working from the memory of a landscape or figure? Using that as a source for your abstract paintings?

GW: I could do that but the thing that fed me for so long in working from observation is that you discover new relationships that one doesn’t necessarily see when you’re trying to reconstruct something from memory. I also have a horrible memory!

LG: I am curious about the connection of your work to music. Hans Hoffman called rhythm the “the highest quality in a work” and he also said: “The general misunderstanding of a work of art is often due to the fact that the key to its spiritual content and technical means is missed. Unless the observer is trained to a certain degree in the artistic idiom, he is apt to search for things which have little to do with the aesthetic content of a picture. He is likely to look for pure representational values when the emphasis is really upon music-like relationships.”

Leland Bell, also stressed musicality when he said “Everything… has to be resolved through rhythms. You’re constantly massaging each form, trying to get it home, pushing further and further until these all coalesce into a marvelous kind of rhythm that reveals the life of the painting.”

LG: What might you be able to say about the connection of music to your work? Would listening to music while painting interfere or help with the process of creating musicality, rhythm in your work?

GW: Music and dance are critical to me. Even though I’m not a performing artist, those modes of movement, rhythm and sound are so important. So, on some level I don’t think it matters what my subject or style is as much as that I get that kind of rhythmic patterning that I like so much in music and dance.

I just saw the Twyla Tharp Company a couple of nights ago perform a 45 minute piece based on J.S. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier. So all afternoon today I’ve been listening to Bach- thinking that his notation is not unlike what I’m trying to do with paint.

I collaborated with a composer colleague, Pablo Ortiz, last fall for Art Silicon Valley/SF Art Fair. He chose one of my larger paintings, “Restraint” and wrote a short composition for two flutes. Once I heard his piece, I wanted to paint another “faster” painting to match the pace of his piece. Listening to music definitely helps loosen me up to explore new rhythms in painting. It can be anything, from Amy Winehouse to Sigur Ros or Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

LG: Gesture also seems very important to your work.

GW: Gesture is what animates my painting–it goes back to choreography and musical composition. I do listen to music as I paint–all kinds while working. It functions as another tool to unglue my mind from the everyday and instead focus on rhythm. I also try to watch contemporary dance like that of Merce Cunningham.

I want my paintings to have an excitement and energy in movement–pushing me to embrace more than I initially thought I could. I sometimes feel that my paintings show a side of me that I don’t reveal in my everyday life–exuberance and high energy!

LG: What stimulates you to begin the improvisation in your paintings? Is it possible to talk about how particular gestures, shapes and colors evolve in your work?

GW: Improvisation requires a suspension of planning. Sometimes it is just putting down colors and marks to see if they respond to one another. I think about Albers’ color theories and how relational colors are, using neutrals to contrast with higher keyed color. There is a lot of erasure in my process, and those obliterated sections of a painting give a depth to the image. I look for movement and gesture to push a painting forward.

“Improvisation is at the root of my practice—responses to the way a particular color or mark leads to another… Untethering myself from the demands of representation has allowed me to abandon the restrictions of a horizon line and naturalistic colors, and to explore without restraint some of the same issues that I had explored in landscape–dynamic, edgy movement, spatial complexity and atmospheric color and light… Speed, movement, gesture, allusions to the body and to landscape are all embedded in these paintings.” from “Gina Werfel – Persistence of Vision” catalogue

LG: Another great quote from Hans Hofmann quote has him saying: “Nature’s purpose in relation to the visual arts is to provide stimulus—not imitation… From its ceaseless urge to create springs all Life—all movement and rhythm—time and light, color and mood—in short, all reality in Form and Thought.”

As an Abstract painter, what aspects of painting from observation, do you feel is most important to teach in the studio classroom today?

GW: I love your Hoffman quote! Painting from observation teaches one how to “see” and we painters have a responsibility to teach our students how to see better than the average viewer. How does one learn to see space as a container that encloses figures and objects and that drawing is less about the documentary depictions of disparate objects or human figures? Also how can the exactitude of seeing lead to abstraction? In my own teaching, I use the perceptual approaches of Mercedes Matter, Charles Cajori and Nick Carone. They each taught drawing from the model as a network of intersecting planes and critical points in space. One didn’t just focus on the model but used him/her to locate points and planes.

LG: Can you speak about the importance of drawing in your work? I understand you also taught a NYSS Drawing marathon? What is that like?

GW: I don’t draw on a daily basis that much anymore except when I am traveling and in museums, but the presence of drawing is in most of my paintings- I am using the colored marks as a notation of space. I taught a marathon for the first time in September at the NYSS and I had a great experience. The title of my marathon was “Perceptual Abstraction” and I used various approaches to spatial organization to get the students to undo their habitual practices. The results were exciting to witness. The intensity of 9 hour days with models created an almost athletic disciplinary milieu. No one was allowed to sit down or take long breaks!

LG: What helps you best decide that the painting is complete?

GW: Completion of a painting is the hardest thing for me to decide. I work on several paintings at once and find that I keep working on them even after I think they were done when I left the studio the day before! Sometimes it is a studio visit and a visitor’s casual observation about a painting that opens up my mind to see it differently.

LG: What have you been currently working on that might be of interest?

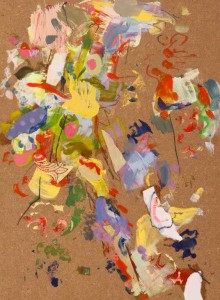

GW: A newer development in my work has been the works on paper in acrylic and collage. I have taken risks that are harder to translate in the larger more sustained oil paintings. I never seem to tire of working flat on several pieces on the floor. The satisfying moment of gluing a small piece of paper to mark a point is still thrilling as well as being able to walk around a painting while working on it. A colleague was in the studio recently and he suggested that I should find a very large brush that I’d attach to a long stick on my back so I couldn’t see my marks as I made them while moving around the studio. I love that idea!!

LG: You’ve been a Professor of Art at the University of California-Davis since 2000. Wayne Thiebaud taught there for many years and UC Davis has a reputation of being among the best schools for studying painting. I understand you were instrumental in bringing Rackstraw Downes to speak at the Betty Jean and Wayne Thiebaud Endowed Lecture at UC Davis. What can you say about your experience at UC Davis and recommend to someone considering studying painting there?

GW: I have loved my time here at UC Davis. The legacy of the founding painting faculty- Wayne Thiebaud, Manuel Neri, William Wiley, Roy deForrest and Roland Peterson- is still richly present. Wayne is someone with whom I love to talk painting and I was excited to be given a chance to name our new endowment in Betty Jean and Wayne’s honor. Rackstraw Downes was our first speaker and Peter Schjeldahl will speak in March 2016.

I would encourage students to attend our MFA program if they wish to paint in an open and interdisciplinary environment rather than staying within a community of painters. I think differences in practice stimulate our MFA candidates to test their own boundaries.

I have also been team teaching first in Italy for four summers and now in France for the past five summers with my husband, Hearne Pardee, also a Professor of Art here at UC Davis. It has been an intense but fantastic experience each time. I love combining studio-based teaching with drawing in museums while living abroad.

I also taught for Yale’s new liberal arts college, Yale-NUS in Singapore last winter- it was my first trip to Asia and it just exploded my mind! I worked on paper and began to incorporate Chinese decorations into my paintings–pushing the layering of space with stencils of these forms. Yale-NUS also invited us to teach a collaborative weeklong class with the Sorbonne in Paris last summer and that too was a fascinating experience!

I have known Gina and her work since the 1970’s and discovered new things about her transition from plein air landscape to studio invention

I think her comments about the benefit of “erasures and restating” marks shows how she is allowing the space to unfold as a kind of illusion of space without the reference to immediate subject matter

Color has always been an important synthesis for her work and she brings a wonderful invention to it now too.

A terrific interview.

This interview with Gina Werfel meant so much to me! I, too, am leaning or just starting to abstract in the studio after years of outdoor plein air painting. At times I abstract AND plein air paint which I also enjoy. Sort of like “bending” the real with color and form. I love your work Gina and will read this interview when I become frustrated. I love to allow the paint itself to speak more. This painting journey makes every day an adventure! Thanks.

Thank you for this interview with Gina Werfel. I have been a fan of hers for a number of years.Its exciting to see her evolution in painting and to hear about her history and influences. I also love Gretna Campbell’s landscape paintings…very underrated brilliant painter.

Thank you for introducing Gina Werfel to me. I responded to her work on a visceral level and greatly enjoyed her discussion on her painting process. I am pushing myself to be more free with brushstrokes and her work is inspirational. I will continue to follow her in the future and look forward to your other interviews of painters in the future.

Yes! What a pleasure to see this new work. Wonderful to see the it getting off the ground and taking flight!