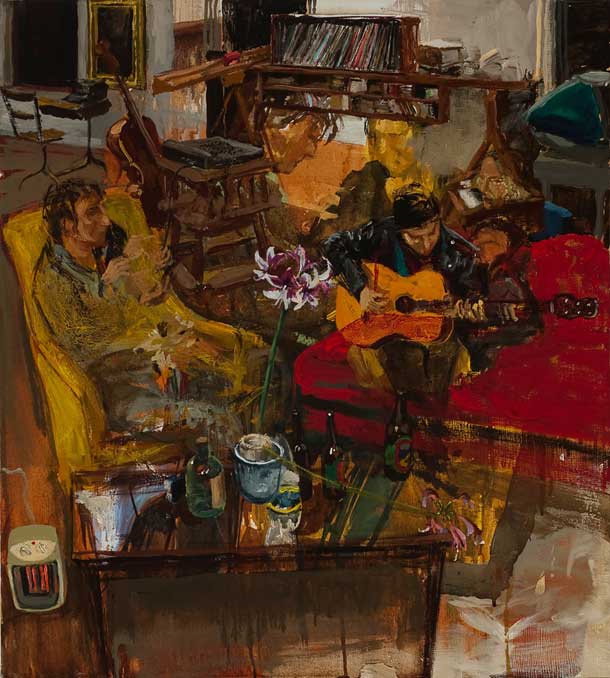

Gideon Bok King of Nails 2006-2010 oil on linen, 70 x 79 inches

Guest Post and Interview by Erik Halvorsen

Throughout art history, the traditional perception of a painter’s studio is one of tranquil solitude. A space where things remain rather constant, save for the quiet accumulation of canvases in various states of completion. Gideon Bok’s depictions of his own studio stand in sharp contrast to this notion. Bok’s paintings are of a lively space, seemingly in a constant state of flux. Working primarily from direct observation, Bok seeks to record the passage of time in his studio – the continuously changing light conditions, the movement of furniture, bottles, vinyl records, and musical instruments, and of course, the steady stream of guests that stop by for an impromptu jam session or quiet chat on the sofa.

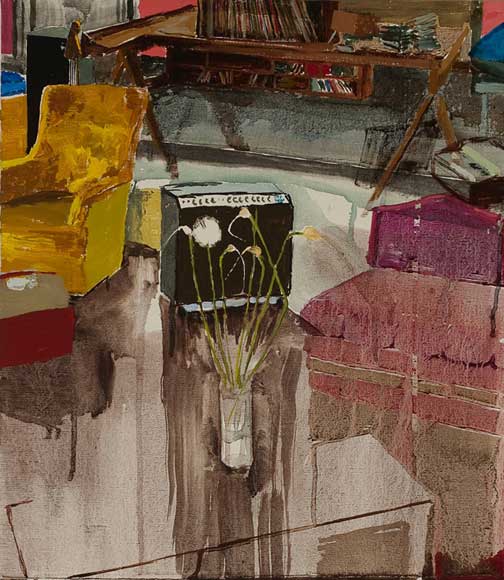

The paintings themselves are as vibrant as the spaces they portray. Translucent layers of thin paint reveal much of Bok’s process, inviting the viewer to consider the painting as a living object in the midst of relentless stages of development. People and objects in Bok’s canvases are represented by swift, gestural strokes often painted over the ghosts of past visitors or furniture that once occupied the same space. Thicker, more deliberate marks are saved for the architectural features of the room and serve as a foundation upon which fleeting moments may be continuously added and removed.

(Click for much larger – full image) Detail from of King of Nails

King of Nails 2006-2010 oil on linen, 70 x 79 inches

Throughout art history, the traditional perception of a painter’s studio is one of tranquil solitude. A space where things remain rather constant, save for the quiet accumulation of canvases in various states of completion. Gideon Bok’s depictions of his own studio stand in sharp contrast to this notion. Bok’s paintings are of a lively space, seemingly in a constant state of flux. Working primarily from direct observation, Bok seeks to record the passage of time in his studio – the continuously changing light conditions, the movement of furniture, bottles, vinyl records, and musical instruments, and of course, the steady stream of guests that stop by for an impromptu jam session or quiet chat on the sofa.

The paintings themselves are as vibrant as the spaces they portray. Translucent layers of thin paint reveal much of Bok’s process, inviting the viewer to consider the painting as a living object in the midst of relentless stages of development. People and objects in Bok’s canvases are represented by swift, gestural strokes often painted over the ghosts of past visitors or furniture that once occupied the same space. Thicker, more deliberate marks are saved for the architectural features of the room and serve as a foundation upon which fleeting moments may be continuously added and removed.

Gideon Bok lives and works in Maine. He earned his MFA from Yale University and BA from Hampshire College. He was the recipient of the Hassam, Speicher, Betts and Symons Fund Purchase Award, The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2005 and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 2004. He is represented by Alpha Gallery in Boston where an exhibition of recent paintings from his Rockland studio is on view until May 5. If you’re in the area, I strongly suggest stopping by. He also maintains a blog where he posts images of new paintings and works-in-progress.

Mr. Bok very graciously took time to answer a few questions for Painting Perceptions about his life, work, and influences. I hope readers find his thoughts to be as engaging as I did.

Erik Halvorsen – Can you begin by talking a bit about your education – your time at Hampshire College, NYSS, and Yale? Were there any instructors who had a significant impact on your development during this time?

Gideon Bok –

I transferred to Hampshire with the idea that I’d study stop-motion animation, as a way to fuse my interests in making music with visual arts in a narrative context. The film and animation classes were hard to get into, so I took a sculpture and figure drawing class with Bill Brayton, who reinvigorated my interest in drawing from the figure, and introduced me to ways of thinking about sculptural form within an abstract context. Denzil Hurley introduced me to working ambitiously about abstract painting ideas, while Riley Brewster engaged a poetic sensibility to ideas of gesture and surface. Judith Mann was excellent for teaching about rendering objects and figures in space. I spent a summer at the new york studio school, which was an amazing and exciting immersion into the figure. I painted and drew the figure all day for five days a week, working with Graham Nickson, Matthew Radford and Riley Brewster.

I was very lucky to get into Yale’s MFA program when I did. While there I worked closely with William Bailey, Sam Messer, Rochelle Feinstein, Natalie Charkow, Frances Barth, John Hull, Laura Newman, and Mel Bochner, among others. Each of these professors had a memorable impact on me, but my fellow students were at least as influential to me as the professors, and probably more

Stephanie Pierce with Ma’s Mango 2008-2010 oil on linen, 20 x 18 inches

EH – How were your early paintings different from your current work? When did your studio space become the subject of your paintings?

GB –

While at Hampshire, I became increasingly interested in the language of paint within an abstract context, and of formal issues, but I also wanted to explore a more ambitious, ongoing engagement with rendering objects and figures in space. My attempts at pure abstraction were terrible, but pure ‘rendering’, or figuration for its own sake seemed limited in interest, as well. For a long time during my time at Hampshire, I led what my professors thought of as a schizophrenic studio practice. I would make carefully rendered figure paintings, cubist still lifes, fauvist landscapes, collage installations, films, sculpture… the list goes on.

As a method towards bringing these ideas together, I began making paintings of what was right in front of me, which was a chair in my studio. I thought that if I made paintings of this neutral subject matter over and over I might be able to explore the abstract, formal and painterly issues I was interested in, while having clear visual parameters to look at and work from. During this time people would come in to visit and I would paint them into the paintings and then paint them out when they left. As I painted the people in and out I would notice the impact on the space their gestures had within the context of the painting, and the painting seemed to hold a clear history of the figures’ presences.Over time, the paintings became more dense with visual information and surface, some of the paintings becoming very thick. Using the paintings as something of a vessel for exploration over time allowed me to be more inventive with ways of painting while embracing the idea of destroying what I thought was cool in the painting. In other words, I became less precious with the paintings and as a result they got better.

While at Hampshire, the paintings would always resolve to a relatively simple composition, with all of the history of the painting having been buried under paint or effaced through erasure. Later, while at Yale, I began working with transparency more, as a way to retain some of the history of the painting while keeping the painting from becoming too thick. As a result, the paintings became more dense with information, objects, and ?gures, sometimes to the point where the space and the objects within the painting seemed to dissolve into a sea of abstract marks.

Day Triptych, 2010 2010 oil on linen, 35 x 96 inches

EH – One of the joys of looking at your work is that they are not mere depictions of a particular time and space – they literally evolve before your eyes. The structure of the room remains constant, but the contents and light are in a constant state of flux. Can you talk about why you’ve chosen to work this way? How do you decide what stays and what goes? How do you decide when a painting is complete?

GB –

One of the issues specific to painting that interests me is the idea that the painting is a single static image (or depicted moment of consciousness) that is made up of thousands of moments of consciousness, or thoughts, each represented by a gesture, mark, or impulse on the surface. In this way, painting collapses time in a specific way. The sense of time in the reading of a painted image is up to the viewer, and is probably different for each viewer, but the fact of the time of making the image is different. Even while working quickly, painting is a slow process. Each gesture requires a specific color to be carefully mixed from a combination of others, and impacts and changes all other gestures in the painting by its inclusion. This constantly shifting and delicate balance of visual spatial issues is what makes what would otherwise be a mind-numbingly boring task fascinating. One moment there can be confusion or disorder, but a carefully placed moment of color can suddenly unify or enliven the space in a way that can seem like magic.

In my painting practice, I try to be clinical with my decisions; if a couch has been moved from where it once was, I change it in the painting. If I painted someone sitting on a couch and they leave and now there is a guitar where they were sitting, I paint the guitar on top of the figure. I don’t tell people to sit still, and they don’t; I follow their movements in the painting, and as a result of this, people are very seldom fully realized. Often the figures are quite sketchy or badly painted, especially the jittery people. If it’s a daytime painting, often the light changes over the course of the day, which affects the light on the objects or the people, but the overall light of the space remains constant. Each painting has its own set of rules, but generally speaking the architecture becomes fixed early on in the process according to compositional decisions (the painting remains loose for a while, I move things around until the composition seems interesting or somehow right, then it becomes more or less ‘fixed.’) After this, I continue to make adjustments according to drawing, measurement, or general perceptual errors, but most of the time the architecture continues to become more solid after this point. The reason for this is to provide a scaffolding for me to refer to and to measure against while everything else is shifting over time. Generally speaking, the things in the studio that sit still for the longest become the most clearly realized or rendered, while the things that are the most dynamic are the least realized. By ‘realized’, in this case, I mean rendered, or visually made ‘real-looking.’

The question about when a painting is complete is a tricky one. (The simple answer is, when it has to go off to a show, it’s done, if it comes back from the show, it’s not done anymore.) I think it’s different for each painting. There seems to be a pattern that happens with paintings that involves working on them for a long time until something interesting or surprising happens. Usually, for the painting to be “good”, there is a breaking point, or moment of reckoning with the painting. This moment of reckoning often will require me destroying what I most like about the painting, or making a dramatic shift in what I had been thinking the painting was about. If this shift doesn’t happen, the painting will usually sit around until I can’t take it anymore and I’ll impose a dramatic change to it, like overlapping a new space on top of the old one.

EH – Obviously, music plays an important role in your work. Can you discuss your musical influences and how they have impacted your work as a painter?

GB –

I used to play music much more ambitiously than I do now, although I still play. For a long time I felt tormented by the idea that I had to choose between visual arts or music. After a while, though, I found a way to incorporate some of the ways I found making music interesting with my painting practice. During the making of a painting I often think in musical terms when it comes to painting problems. I also listen actively to music while I’m painting, and I tend to focus on music that gets better the more times you listen to it. One of the people who this works well with is Neil young, who I’ve listened to on continual repeat ever since I began this project (back in 1991,) especially the work he has done with Crazy Horse. Often his records will mildly (sometimes not so mildly) irritate me when I first hear them, but gradually after a few times through the album, it will start to grow on me. One of his records, ‘Sleeps With Angels’ really opens up after about the 100th listen, and then continues to get better with each successive listen. I have listened to that record (literally) thousands of times and it keeps getting better. Other people who have had a big impact are: Sparklehorse, Elliott Smith, Joanna Newsom, Boris, Gavin Bryars, Iron & Wine, Mike Ladd, and Bon Iver, among many others.

Re: Re: Stacks; Garlic Scapes 2010 oil on linen, 16 x 14 inches

EH – Who are some of the past or contemporary painters who influence or excite you?

GB –

Probably my favorite artist right now is David Ellis, but I don’t think he’s considered a painter. In terms of painters, I’m very lucky to be married to one of my favorites (Meghan Brady.) Every time I walk into her studio she’s done something that surprises (sometimes shocks,) inspires, and influences me. Angela Dufresne is doing amazing stuff lately, and Nicole Eisenman is responsible for probably the best show I saw last year. Dana Schutz is doing great stuff, as well. Stephanie Pierce, Joe Wardwell, Amy Sillman, Jackie Gendel, Elena Sisto, Ellen Altfest, Chie Fueki, Michael Berryhill, Josephine Halvorson, WIlliam Bailey, Jenny Dubnau, Gina Ruggeri, Norbert Schwonkowski (I might not be spelling that quite right) Vera Iliatova, Keltie Ferris, are all people who have reinvigorated my feelings about painting recently, and who are doing exciting things with it.

The list of historical painters who influence or excite me is too long to go into, but lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Zurbaran, Artemisia Gentilleschi, Balthus, Bonnard, Manet, and, as always, Picasso and Giacommetti. I consistently steal ideas from, and make tributes to all of these artists as I’m working.

Many thanks to Eric Halvorsen, a painter living in the Boston area, who so kindly contributed his time and energy in making this interview happen. – Larry

Wow, this interview is very interesting. The paintings are just great, I am impressed. As being a synesthesian artist I live a life in colors. Synesthesia means that I see colors when I see words and numbers.I transform this in paintings of names and birthdays.

Great…now I have to go look up ‘fauvist.’

Nice interview. Without a doubt one of the most exciting ‘perception painters’ around.

I remember Gideon from Yale. I was coming in when he was going out. I also remembered his paintings. They were unique and interesting then, and looking at these pieces in the article makes me exited. he is a good painting and he offers something unique in his work. The interview also helps illuminate the thinking in his paintings although his paintings are clear enough to understand. “Gideon” I am watching from a distance and I like what I see. I hope to see the work in person some day.