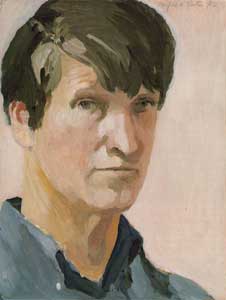

Fairfield Porter Self-Portrait 1972 oil on masonite 14×10 inches

Part Two, On Fairfield Porter

Larry Groff:

You were friends with Fairfield Porter and had gone painting with him, on occasion, during the early ’60s. Did you talk with him about your paintings and about the difficulties of painting from observation, when most everyone else was painting abstractly?

George Nick:

Really weird for you to ask those questions, because we never discussed any of those issues.

Let me tell you about Fairfield. He had come to visit at Yale, and we had a drawing class that drew these immense, very careful, large drawings of elephant skulls or something like that. They were worked out by crosshatching and everyone made them into paintings.

I was so impatient, I would do like a dozen drawings and leave class. It was like a three or four-hour class, and I didn’t have the patience to study like that with drawing. I did washes or I did little ink drawings. I never knew who he was. He came by to critique once, and he came over to me, and all I know is he said to me, “You know, I’d do it that way.”

Later on that evening, Welliver called me up and said, “Listen, Fairfield wants you to come over for dinner. We’re going to have dinner over at my place. Would you like to come over and have dinner with us?”

I didn’t learn much, except they didn’t talk very much. I rather liked him. He was sort of quiet, and Welliver, with his kids and his wife — it was a sort of madness.

But I met him again, and we became friendly. When I was in Boston and he was in New York, or I was in Philadelphia and he was in New York, he would call me up and say he was going into New York. He lives in Southampton. “I’m going to New York and look at some shows. Would you like to join me?”

And so, I would meet him, and then we would go see some paintings, and I remember taking him over to Pearlstein’s house on 88th Street and introducing them. And then he took me to a restaurant on Madison Avenue for lunch. We met the Soyers brothers. Do you know the Soyers?

LG:

Oh, yes.

George Nick Greenfield Gas Station 1963 oil

George Nick:

Very nice people.

LG:

They were both painters. Their names escape me, right at the minute. Raphael and …

George Nick:

Raphael and Isaac.

LG:

Isaac. That’s it.

George Nick:

Raphael I knew, I could talk to. I think Isaac was much quieter.

Anyway, I remember after I met him, Raphael came to my opening at Fishbach there, on 57th Street, and he came up to me and he said, “Mr. Nick, I want to tell you how much I appreciate your paintings.”

And I said, “Thank you very much.” He turned around and walked away. That’s all I ever saw of Raphael Soyer. Things like that happen with Fairfield.

Then he had an opening, and I met a lot of people there. I didn’t talk to anybody; I talked to him, but was too embarrassed to talk to many others.

Once he saw a painting of mine, he said, “I like that painting.” And that was it. Nothing else was ever said about my paintings, and I never asked.

And then the business about difficulties of painting from observation when everybody’s painting abstractly, we never talked about it. I don’t know why. All I know is that we would talk about what to paint, that’s all.

He would come out, and he would say, “What about this as a subject?”

I would say, “Well, that looks good.”

And then he would say, “Why don’t you use black oil?”

I said, “No, I’ve been there, done that. I don’t like black oil.”

And he would put black oil over the front of his pochade and he’d get one of this Egbert brushes and start whipping around, in that wet stuff on the canvas — I think it was a canvas board.

We had that kind of relationship. He invited me once to come up there, and visit with his family. In the hallway, I remember there was a drawing. I couldn’t recognize it. It was a line drawing of a church, and he said, “Do you know who did that?”

I said, “No.”

He said, “That’s a Turner drawing.”

I would never have guessed it was Turner. I knew his wash drawings and more imaginative things. I never knew he was that technically so facile.

Then he had a studio upstairs, that was in a barn, on the second floor. He would paint up there, It was a barn in Southampton. It had a linoleum floor, I remember. He had a taboret, and on the taboret, he had about seven whites on the side— and he would have tints next to the white, of blue, red and yellow.

And he said, “[Do] you know which one is the best?” He said, “This one, Weber’s Permalba.”

And he said, “I like it because of its and the tints over the years faded the least.”

And I found out later that I could make that out of lead white, which is like cement, so you can make any viscosity you want. Then I found out that Permaba was a simple mixture of titanium and zinc.

Fairfield Porter Amherst Campus, No. 1 1969 oil on canvas 62 x 46 inches

George Nick:

There’s another aspect about him that I like. He had a wonderful, kind, quiet nature, and he was ever a responsible person as a friend. He was sort of distant, but always there. I would call up, and if I didn’t call up in a while, he would call me up. So it was sort of nice.

LG:

That’s great. He’s very verbal in his art criticism.

George Nick:

One day we went out, we saw a show of Dickinson’s, and a show of Bonnard’s.

He said to me, “You see? Dickinson’s like seeing death, Bonnard’s like seeing life.”

I think he really respected Dickinson, though.

LG:

Did he know him?

George Nick:

Yes, he knew them all.

LG:

I don’t remember reading anything that he’s written about …

George Nick:

There is a book that Rackstraw put out on the criticism of Fairfield. Rackstraw Downes’ book? He wrote about his criticism, and he quoted a lot of it. And there is one essay that is about Dickinson.

LG:

Oh, I’ll have to look for that.

George Nick:

But we never discussed art of the day.

LG:

So you didn’t get into big arguments about de Kooning or anything.

George Nick:

No, I don’t think we ever talked about him. He just said that he was a good friend of his, that’s all.

LG:

Right. Interesting.

George Nick Portsmith, New Hampshire 1967 oil on canvas – collection of Bob Dylan

George Nick:

You can see where he was influenced by action painting, because some paintings have the very great bravado, and they are very dangerous and very inventive, and some are more classical. But he was always having this inside argument about how far to go. But that’s only from what I saw, It’s not that he said anything about it.

I could have brought it up, and he would have been glad to talk [about it], but I somehow never did.

We talked about more fundamental things about, “You like to put cars in your paintings?” or something like that.

LG:

He was more or less self-taught, in many ways. Is that true?

George Nick:

I read about it. I found out that he went to Harvard. I think he went to Europe for a while, but I think that’s so, yes.

I don’t know who of the artists that I admire who aren’t mainly self-taught. I think Rembrandt had a nice teacher — I forgot his name — when he was really young. But he very quickly went his own way.

And I think that Monet studied under, was it Boudin, who did those beach scenes?

LG:

Oh right, yes.

George Nick:

Was it him? And Matisse studied with — God, I can’t remember his name, now — for six years. I have to look it up. And at that same time, he spent six years copying a large Chardin of that cat jumping up with that ray. Do you know that painting?

LG:

Yes, yes. I don’t know what kind of ray it is — some kind of ray fish.

George Nick:

He spent six years studying with this fellow, who was a good painter. I forgot him name. I keep on saying, Bouguereau, but it’s not him; somebody else. At the same six years he spent copying this painting, and he was finished with both of them at the same time.

To Interview with George Nick, Part One, On Edwin Dickinson

To Interview with George Nick Part Three, On George Bellows

To Interview with George Nick Part Four, On Cezanne and color

To Interview with George Nick Part Five, On Drawing

To Interview with George Nick Part Six, On The Trojan Horse and thoughts on Teaching

Please tell George that I am certain it’s Moreau. I am certain of it because it was George who told me that.

Dik, YES, Moreau is right. Also, the book by Porter is called ‘Art in its Own Terms’. It was actually re-issued early this year, i believe, harder to find otherwise, i ordered a copy.

Having just discovered this website, I am now hooked! Lovely work.

Great interview. I had Welliver as a teacher and he loved to tell this story about Fairfield Porter: The two of them were walking around Neil’s property in Maine and Fairfield said to Neil ” Neil, you use too much green in your paintings.” Welliver replied” Fairfield what the **** are you talking about. Look around you” Fairfield paused and without missing a beat said” Neil, you don’t use enough green in your paintings”

I’m enjoying these interviews. Great fun to read. Thank you, George.

I studied with Porter at Amherst in 19760, corresponded with him and collected his letters (Material Witness, The Selected Letters of Fairfield Porter). His studio visits were like visitations. He would come in without a word, maybe speak, maybe not, then leave without a word. He remarked one time,” You like pointed shapes.” another time, of a painting that was wrinkled with too much oil medium, I’m envious of that painting. I should use more oil…” He was not good at teaching technique, at least not drawing, but he was a profound teacher for me. He took me more seriously than I did myself. His letters were as long and dense as his visits were sparse. Not only would he expound on his latest thoughts about esthetics, but he answered me with startling honesty. I once asked him how his painting was going and he answered that he always felt that he was “cliff hanging,” that he was never sure immediately whether a painting was any good.

I studied with Porter at Amherst in 1970, corresponded with him and collected his letters (Material Witness, The Selected Letters of Fairfield Porter). His studio visits were like visitations. He would come in without a word, maybe speak, maybe not, then leave without a word. He remarked one time,” You like pointed shapes.” another time, of a painting that was wrinkled with too much oil medium, “I’m envious of that painting. I should use more oil…” He was not good at teaching technique, at least not drawing, but he was a profound teacher for me. He took me more seriously than I did myself. His letters were as long and dense as his visits were sparse. Not only would he expound on his latest thoughts about esthetics, but he answered me with startling honesty. I once asked him how his painting was going and he answered that he always felt that he was “cliff hanging,” that he was never sure immediately whether a painting was any good.

These interviews are fascinating. Thank you.