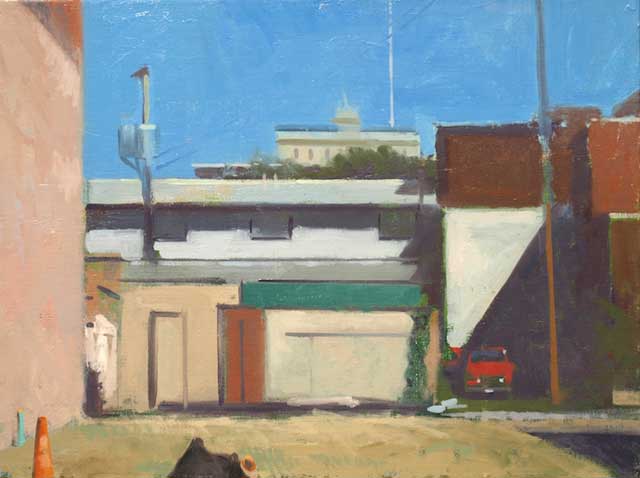

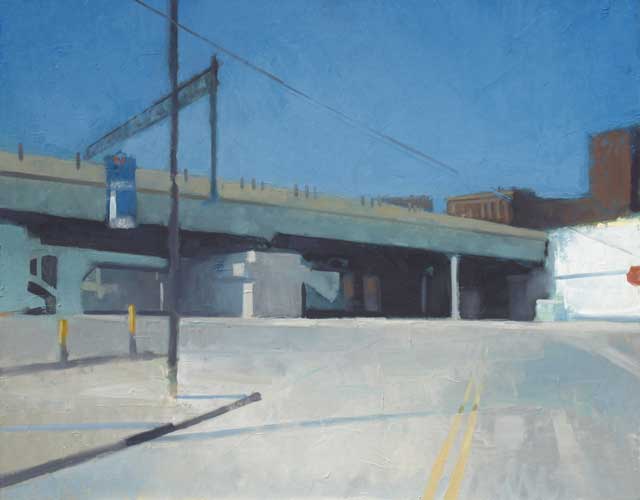

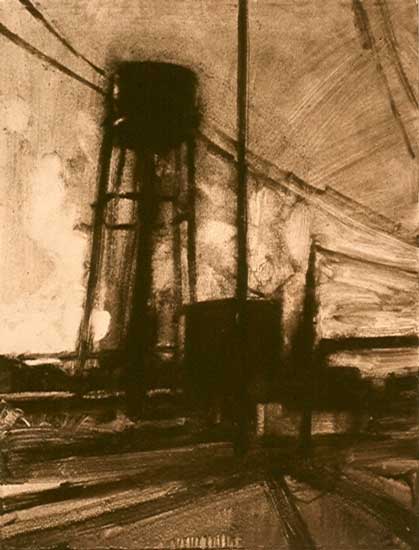

Frank Hobbs, Gas Works & Trailers, January Light, oil on canvas, 36″ x 48″, 2013

click here for a larger view

I enjoyed meeting Frank Hobbs in Civita, Italy last summer where he gave a slide talk during his visit to the JSS summer Italy program. I’ve also enjoyed following his writings on painting and drawing on his blog I was very pleased that he agreed to this email interview and would like to thank him for taking the time to share his thoughts, experience and art with Painting Perceptions.

Frank Hobbs is a Professor of Art and teachs painting and drawing at the Ohio Wesleyan University. Hobbs is a recipient of fellowships and grants by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Virginia Commission for the Arts, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. His work has been shown in the American Embassies of Ankara, Turkey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and Bermuda, and is included in numerous corporate and private collections in America and abroad. He is represented by the Reynolds Gallery in Richmond, Virginia and several others.

Larry Groff: How important is observation to your work?

Frank Hobbs: Everything starts with sensation, doesn’t it? Our physical contact with the world is the most private and intimate experiences we have, but we overlook it, or depreciate it because it’s so familiar. In working from observation there is this struggle to reclaim some of the lost wonder and innocence of perception that allows you to really see and experience things, as they say in Zen, in their “suchness.” Most people, artists included, are more interested in opinionating. I’m deeply suspicious of my own opinions. That’s what I’m fleeing from when I paint. Degas said the only way forward is to accept that you know absolutely nothing about anything. From that position there’s nothing you can do but ask questions.

Working from observation is where I think I first started to get traction as a student, because it put a missile to my whole youthful preoccupation with “style” and got me involved with a more complex reality than I could fabricate from my own head. Bischoff talks about how nature led him out of the “cooked up artificialities of abstract art.” That was my path as well. My artistic identity then just congealed around the practice, particularly painting outdoors. Landscape is the juggernaut that I have kept pushing forward for several decades now.

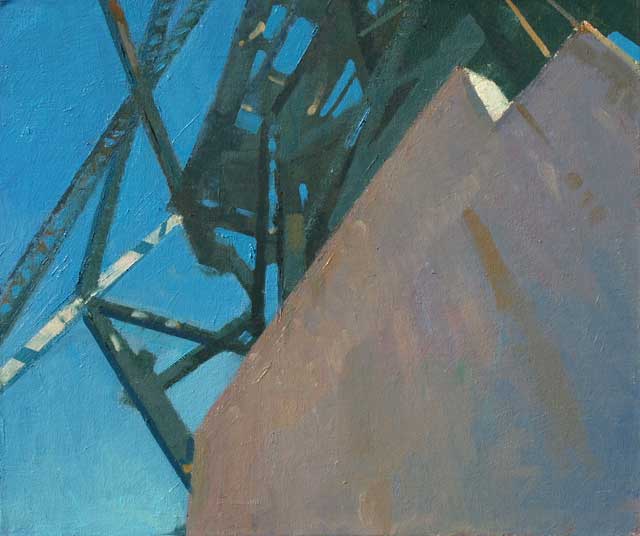

Abandoned Factory: Steel Cylinders, oil on panel, 16″ x 20″, 2013

Abandoned Factory Near Poppi (Italy), oil on canvas, 16″ x 20″, 2013

Cylinders and Cubes – South Columbus oil on canvas 20″ x 16″, 2011

LG: Can you tell us something interesting about your background? Where did you study and which painters have most influenced you?

FH: As an undergraduate I studied at Virginia Tech and later got my MFA at American University in Washington, DC. My teachers at Tech were in their 30s when I was there. I think the most important thing I got from them was a belief in the vocation of painting as a way to live my life, and a confidence in my own resources. My teachers at American were older and helped me to begin answering the questions I found myself asking about how painting works as a representational medium.

Ray Kass at Virginia Tech was an important mentor to me, and still is to this day. It took me several years and a lot of growing up to realize just how important he was in shaping my outlook as a painter. Ray put my young nose in the paint, so to speak. His teaching planted the seeds of a certain formal awareness of the language that I’ve never lost, even though I moved away from abstraction toward representation. I still think like an abstract painter.

There was a group of us at Tech who used to tag along with Ray to New York to help him transport work to his gallery. He would have us around to meet some of his artist friends in New York and see their studios. Marjorie Portnow and Susan Shatter were two contemporary painters who had an impact on me in terms of shaping my view of what it means to be a painter. At that age you read between the lines and get an idea of how this thing, this being an artist, is done. That demonstration was a lot more powerful than lectures or slide talks.

One year out of college, I had an encounter with Wayne Thiebaud that was monumental, again thanks to Ray Kass. For many years Ray had been building the Mountain Lake Workshop program, his vision for a trans-disciplinary approach to art criticism, studio workshops, and experiments with group collaboration. Greenberg, Donald Kuspit, Suzy Gablik and other notables came through. John Cage was a frequent guest. These symposia were held at the Mountain Lake Hotel, where incidentally the film Dirty Dancing was made, near Virginia Tech. Ray brought Thiebaud in to do a four-day landscape workshop. We got to watch him paint a beautiful small study from the porch. I’ve never forgotten it. My path has intersected with that painting three times since then. First when I watched him paint it. Second, when I shared wall space with it in a big retrospective of Virginia landscape painting at the Virginia Historical Society, and third, strangely enough, in Bologna, Italy, two years ago at the Morandi museum which paired Thiebaud’s paintings with Morandi’s.

Several things about Thiebaud made a lasting impact. First, I guess I expected him to be a flamboyant, loud sort of character, based on his colorful, cheeky paintings. I imagined him making a grand entrance, like some sort of modern Oscar Wilde. In fact he was incredibly ordinary, humble, almost self-effacing. He was the last to be taken in by his own celebrity. At a slide talk he said, “You already know what my work looks like. I want to talk about paintings that I love.” The paintings he admired were the second shock: Rembrandt, Chardin, and other “brown” painters, long dead. He spoke with great love of these and other masters, and he also talked about his values as a teacher of art; that you need these fundamental disciplines of drawing, of wrestling with your own perceptions and the struggling with the difficulties of representing what you see. He required his students to do a six-hour rendering of a single egg with an H pencil! I was hungry for that kind of discipline.

Another thing I remember, a remark he made that was like a bomb blast to my youthful delusions about the issue of originality. He said, “Everything I do I stole from someone else, and if you’re not careful I’ll steal from you!” That sort of gracious self-deprecation and humility is not well-taken in American culture, especially these days when there’s this frenzy of self-promotion aided by technology.

The final thing that impressed me about Thiebaud was his generosity toward other artists. There was a massive critique at the end of the workshop that began after dinner, around 8, and stretched way past midnight into the wee hours. I was only 23 and I’d just done some of my first landscapes so you can imagine my trepidations about having the master cast his eye on my stuff. When my turn finally came the room was almost empty. Thiebaud looked at my little studies – he must have been exhausted at that point. Long silence. I was tempted to pack up my paintings and run! Finally he spoke – something about my paintings being “an eye-wash from Cubist sensibilities…” I don’t even remember what he said. I only remember that he didn’t hate them, and that was enough. I think these encounters with painters were as pivotal in my education as anything I learned in class.

At some level I think we are all self-taught; we develop a nose for what speaks directly to our needs. I’ve come under the gravitational pull of so many great painters over the years and learned different things. Vuillard, his self-portrait, the one with the red beard, really taught me how to paint. That kind of thinking still underpins how I see.

Another pivotal event for me as a student was seeing the huge Edward Hopper retrospective at the Whitney in 1979. The work from his student years – the palette knife studies from Maine and the small paintings he did in Paris – really blew me away. Maybe I identified with that work because I was about the same age, and it gave me a gauge of my own development and what I still needed to learn. Mostly I think it was the connection, like Thiebaud was, to these seemingly lost disciplines of seeing; of perceptual painting. I also was amazed by the honesty of his urban landscapes, which opened my eyes to the aesthetic possibilities of my own environment. That’s when I began to paint the old urban industrial center of my hometown, Lynchburg, VA. Since that time I have had a quote from Henry James tacked to my studio wall: “Take what there is, and use it, without waiting forever in vain for the preconceived—to dig deep into the actual and get something out of that — this doubtless is the right way to live.” You don’t need any special subject matter to get started. Painting becomes more about the quality of your own consciousness than a strategy for depicting something, or “expressing yourself.”

Vestige: Cement Factory Pilons, oil on canvas, 14″ x 18,” 2013

Steel Containers, oil on canvas, 22″ x 30,” 2012

Rust Belt Elegy, South Columbus, oil on canvas, 18″ x 14,” 2013

LG: Many times you make painting seem like great fun. Your blog has a recent post, “Vestiges” which examines your attraction to the decaying industrial landscape and how painting it involves more than just formal interests. You quote from a student saying “These are the places we sought out as children to play in; places where there are no adults.” You then remark; “I haven’t stopped thinking about that since. Play, as every child knows, is the most serious work there is.”

Your selection of what to paint along with the paint handling and color decisions gives us a glimpse into your experience out in the landscape, your joys and struggles. What gets you the most excited about painting outside? What gives you the greatest pleasure in your painting and what do you need in order to get to that place?

FH: I’m glad to know that my paintings have that effect. Frankly, it’s a mystery to me why that should be so. They give me hell when I’m painting them! I suppose art creates an illusion of effortlessness and freedom. Only the artist knows what it’s cost in terms of sheer work and frustration. The joy and struggle you mention is the great roller coaster ride of painting, isn’t it? It scares the hell out of you while you’re on it, but later you think, damn! that was fun; let’s go back and do it again

What gets me excited about painting outdoors? Aside from the occasion to enjoy the sunshine and a good cigar, I think that it’s the sense of potential discovery when I leave the house. To go out the door with no preconception of what you will eventually spend your day involved in may seem like madness to a business mind, but that’s what I love about it. When I drive off in my car, or walk off with my backpack, there’s this sense that anything can happen. Painting outdoors is a little like painting from the model. It kind of removes the whole onus of what to paint. You don’t have to know until you start.

On site, the first things that I respond to are space and light. I really am an abstract painter, I think; or a frustrated musician. Rhythm is more important to me than the particular inventory of things. I love to discover how things connect visually; to find the “liasons” between things, to borrow Lennart Anderson’s term. A searching attitude is important because it allows for the emergence of something new, a transformation of the familiar fragmented reality into something that’s greater than the sum of its parts. A great painting is not just a picture, it’s really a model of how the universe is put together: one energy differentiated into all these seemingly disparate, yet dependent, parts. You see it in Morandi’s table top games, in Corot’s oil studies, and especially in Vuillard’s interiors from the 1890s. Could anything be more thrilling than to make a 14 x 18-inch model of the universe?

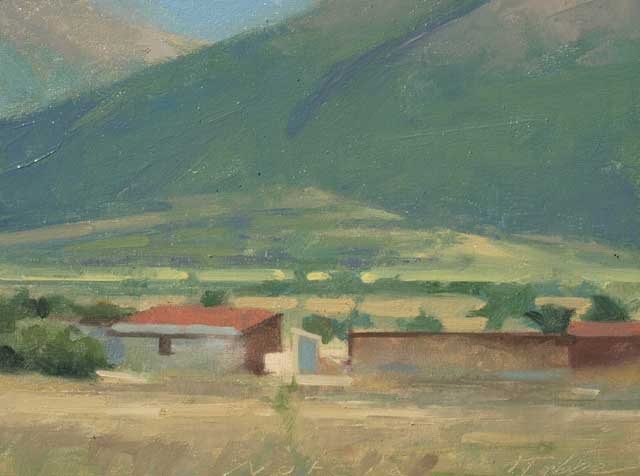

Norcia Periferia Oil on panel 7″ x 9″

Castellucio Oil on panel 7″ x 9″

LG: You’ve traveled and painted in Italy and lived in Tuscany, Italy for some time.

Can you tell us a little about how your experience there has influenced your work?

FH: Ironically, my eyes were mostly on French and American painting until graduate school. It was at American University that Italy first began impinging on my consciousness. Robert D’Arista, my teacher there, once said, slyly, “Only Italians can draw the figure correctly. The rest of you will just have to do the best you can.” We laughed, but he got my attention. I first encountered the Macchiaioli through Jack Boul, another of my mentors, whom he’d seen and been influenced by when he was stationed in Italy in the army. And also on the faculty at American was Norma Broude who at that time was completing her wonderful book on the Macchiaioli. D’Arista would often speak of Piero, or Masaccio, always in the present tense. (That’s the difference between artists and art historians, I think. Artists never die.) He told the graduate students once, as if to warn us of the difficulties that lay ahead, “When you leave here and go out to teach, you will show your students this painting of Masaccio (The Tribute Money), with this old man sticking his finger in the mouth of a fish, and you will have to convince your students that THIS is the stuff of which great art is made…”

To this day the Italian painters who mean the most to me are not the flashy celebrities of the high renaissance or baroque, but the anonymous medieval craftsmen, and the early proto-renaissance masters, like Giotto, Masaccio, or Sienese masters like Sasseta, who were still struggling with this new consciousness of space, light and form. The Caracci brothers ruined Italian painting as far as I’m concerned. Their conceited spawn are still alive and well today all over the globe. In my own concerns as a painter I still feel very close in spirit to the Macchiaioli painters, Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, Giuseppe Abbati, in particular, and at the same time I draw inspiration from the modern Italian painters like Sironi (despite his ties to Mussolini), Fausto Pirandello, and Marino Marini. But Morandi is the one for whom I feel the deepest, and most abiding reverence and awe.

As fate would have it, Tuscany and Umbria have become a second home and that’s where I do most of my painting. I’ve traveled widely in those regions over the years but there’s still so much of Italy I haven’t seen. As a painter I have always had a stronger desire to return, and go deeper into familiar places than to constantly run off in search of new, exotic experiences. That’s how my home state of Virginia always was to me as a subject for painting, and that’s how Tuscany and Umbria have been to me. I think you have to experience a place deeply in order to get past the obvious exoticisms that captivate tourists. If there’s been any consistent thread in my work, or in my concerns as a painter all these years, it’s been this relationship to the familiar, everyday realities; for me this is the geode I have to crack. That’s Morandi’s great lesson to us all. Your life’s work lies in the courtyard just outside your house.

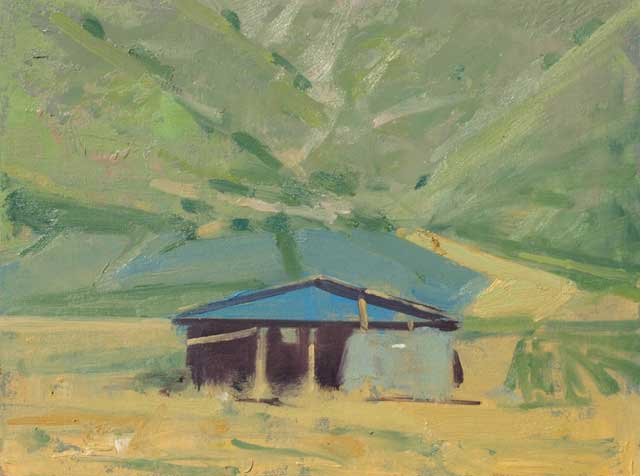

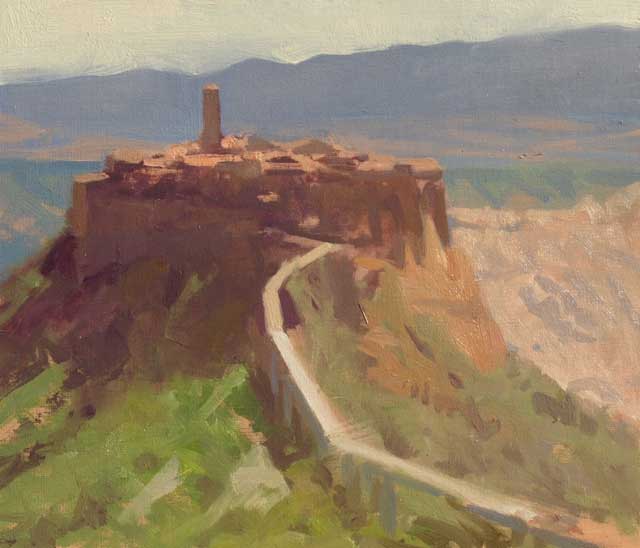

Bagnoregio Oil on panel 12″ x 15″

Castellucio 2 Oil on panel 7″ x 9″

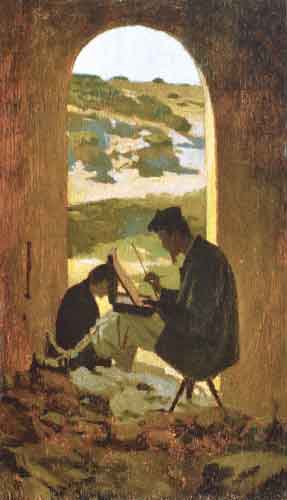

Nino Costa, “Campagna,” circa 1855, oil on wood, 11 x 24 cm.

Giuseppe Abbati, “Il pittore Stanislao Pointeau,” 1868, oil on wood, 35 x 21 cm.

LG: You once posted an album of mostly small pictures from the I Macchiaioli, group of 19th century Italian painters active in Tuscany. In the comments there a great discussion started about the differences between small paintings from life and large studio works like what we see in Constable and Corot. You talked about how many of the studies made by the I Macchiaioli felt refreshingly honest and free of mannerism and artifice whereas their larger history paintings were less interesting.

How important is being free of mannerism and artifice in your own work? What suggestions would you offer for a painter wanting to avoid cliche?

FH: My first piece of advice would be: stop looking at how-to-paint art magazines. What they’re selling is a kind of certainty that avoids the central problem of a painting, which is to find your way to the particular form that expresses your unique experience. Anything else and you’ve only got a souvenir, like one those products of the street painters in Florence who crank out the same views of the Ponte Vecchio for the tourists. I’m talking mostly about “technique,” a word I loathe, by the way, not subject matter. Cliche subject matter is another issue altogether. Depending on who you ask, we’re all guilty of committing that. I’ve actually met museum curators of contemporary art who think the whole genre of landscape is dead and done. (The spirit of Clement Greenberg lives on!!!) I try to avoid the kind of absolute pronouncements that some teachers are driven to, such as “Don’t paint cats!” etc. I used to think barns were cliche until I saw Wolf Kahn’s early paintings. I don’t think there’s any subject so cliche that a brilliant painter couldn’t crack it open and get it to be something new and vital again. It’s what you do with it, and what you bring to it. As my OWU colleague Jim Krehbiel once told a student who wanted to make an image of some flowers, “If you’re going to do flowers, you’d better kick some butt with those flowers!”

Attitude is everything. When you approach painting, as Hawthorne advised, as a “problem,” not a “picture,” it’s a very different game. You bring your knowledge and experience to the problem, but you allow fresh observation to inform your actions and take you where it will without some clear pre-conceived idea of how it will turn out. The making is what makes your intention clear. I know that’s anathema to a certain mindset, but that’s actually the hope and expectation that I always have when I start a painting. If I were clever enough to devise some good mannerisms I might be tempted, but I’m not that facile. Nothing that I did yesterday seems to work today. Ben Summerford, another important mentor of mine at American, said something that took me many years to understand. He said, “Talent paints whatever it desires; genius paints what it can.” For years I thought he’d gotten it backwards. I wanted to be able to paint whatever I wanted; who doesn’t want that kind of ego-gratification? In the end, you find that you can paint well only what is really yours to paint. It’s very counterintuitive that genius would actually depend on that limitation and not on absolute freedom, but I think it’s true.

The Cowpasture River, Bath County, Virginia

Vestige: Cement Factory, oil on canvas, 14″ x 18,” 2013

Ultimately, worrying too much about whether one is committing cliches or mannerisms is a waste of energy. You just have to do your work wholeheartedly and with no ulterior motive. Find where your emotion resides and follow it. Too many painters today are always looking over their shoulder to see who’s watching. Emerson’s great advice was to “gnaw your own bone.” The challenge of course is to find your bone. A mannerist period such as ours wants to hand you the bone. It takes a certain disgust with the tepid bath of pop culture to spur a search for something that’s personal and authentic for you. Deal with your own life is what I tell students. Back to Morandi again. Look out the window, or at the corner of your room. What does it tell you about who you are and where you’ve come? Anyone’s life is complex and strange enough to provide compelling material for art if only we attend to it. Unfortunately that’s what has become so difficult to do these days. We’re always looking for the hyper-link out of the present moment to something else we imagine will be better.

As for artifice, I’m not sure it’s the same thing as mannerism. I think any painter who works from observation must be consciously involved, and in love with, the essential fictiveness of the art form – the intrinsic energies of color, shape, line, proportion and so forth. Annie Dillard’s question to a student who asked her if she thought he could be a writer was: “Do you like sentences?” Like all languages, you don’t just express your thoughts; the language shapes your thought. The picture plane teaches the painter to think in terms of two-dimensional relationships in nature where most people, without that artifice, see only depth and “roundness.” I think that’s what Paul Klee meant by saying that the artist “must conform himself to the paintbox.” Conforming to the paintbox is the first step in learning to paint.

Cleveland: The Flats, oil on panel, 24″ x 30,” 2013

Green Bridge Over the Ohio River oil on canvas 36″ x 48″ 2011

Drawbridge, oil on panel, 14″ x 18,” 2013

LG: I enjoyed the article you wrote for your paintingOWU blog, “Making your mark”

where you talked about the brush and “how something as simple as one’s attitude toward this ubiquitous tool can have such a profound effect on one’s art.” This article contrasted commonly seen student’s neglected, massacred brushes with the past Japanese artists where; “A good brush, in the hands of a Hokusai or a Yoshitoshi was an extension of the body itself – a conduit, or a gateway between the invisible and the visible.”

I love my well-cared for brushes and want to believe in this spiritual connection and reverence to one’s craft. However this belief is challenged when confronted with stunning, brilliant paintings, such as those by Francis Bacon or Anselm Kiefer, where conventional notions of brushwork and technique seem irrelevant.

How can the slovenly make such great paintings? Can’t a broom or crapped-up brush also be delicate and lyrical? Isn’t our bodies just the mind’s brush and conduit between the seen and unseen?

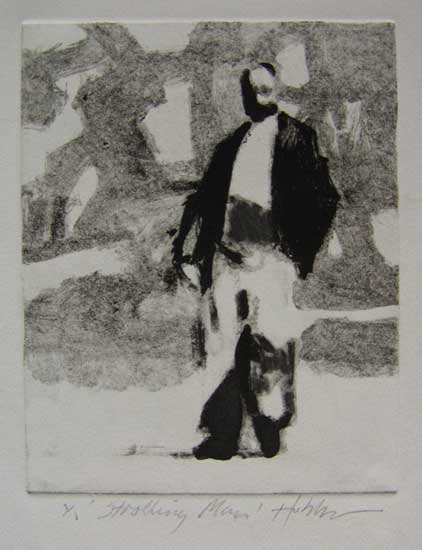

FH: First, I would make an important distinction between the kind of consciousness about tools and materials that a Keiffer or Bacon, or any great painter, has, and the carelessness and neglect that I was taking to task in that article. Keiffer and Bacon, to me, aren’t “slovenly,” nor is any great painter. To be slovenly is to be careless, to be without awareness. I actually have a lot of “crapped-up” brushes that I use in my monotypes so it’s not necessarily the innate perfection of the brush that’s important; just the awareness of its potentialities and having a basic “gratitude” to the tools. Bevin Engman, a wonderful painter I met while I was a visiting artist at Colby College in Maine, makes her wonderful paintings using only scraps of cardboard, but she does it with an exquisite understanding of the tool and what it can do for her. There’s a story I love about a student of Dickinson who was fussing around with a sable brush until Dickinson ordered him to paint with a scrap of wood that was lying on the floor. In the end it’s the right color in the right spot, not fancy brushwork, that makes the painting work.

Silo and Rails, Delaware, Ohio oil on canvas 48″ x 36″ 2011

The Ohio River from Athens County, Ohio, Winter oil on canvas 36″ x 96″ 2011

LG: Outside the universities and the larger urban art centers, the plein air painting “movement” of regional painters has become increasing popular. It’s encouraging to see renewed interest in outdoor painting. It helps give teaching income to established painters and perhaps a wider group of potential collectors. However, the popular nature of plein air movement seems a double-edged sword; more people now care about landscape painting but on the other hand the work often suffers from being geared toward mass consumption.

The deluge of email marketing to painters soliciting workshops such as learning secrets from the masters, plein air contests, and plethora of other marketing ploys for plein air painters sometimes seems to be turning landscape painting more into a sporting, competitive activity and less of an artistic or spiritual/personal exploration of nature.

With this in mind, what thoughts can you share with us about the health of contemporary landscape painting?

FH: The appeal of painting outdoors is not hard to understand and I’ve certainly benefited as a teacher of classes and workshops, but I have very mixed feelings about this current fad, as you obviously do. I keep thinking, who invited all these people to the party? I would rather make a trip to the dentist than participate in one of those “paint-outs.” What sensitive, self-respecting artist could go for that? Some of my best friends actually do these things. I just don’t get that clubby, herd mentality at all. Can you imagine Cezanne doing such a thing? He’d probably kill someone! As despondent as painting makes me sometimes, why would I want to stand shoulder to shoulder, rubbing french easels with a bunch of strangers, especially strangers who define the purposes of painting very differently from the way the great masters saw it; all these dutiful imbibers of how-to-paint books and videos and workshop gurus, coming armed to the contest with their techniques and recipes. As the “good book” says, they have their reward. As far as I’m concerned the orgy of “plein air” painting today, and all the marketing of specialized boxes and gear, painting holidays, and events, just seems to trivialize what is, to me, a very personal, introspective and sacred practice.

Lake Trasimeno from Isola Maggiore, oil on panel, 16″ x 24,” 2013

Pilistri Oil on panel 12″ x 15″

In the Valdichiana Oil on panel 12″ x 7″

Cowpasture River, Winter (VA), oil on canvas, 42″ x 54,” 2013

LG: I’m very concerned about environmental issues such as climate change. Hurricane Sandy directly affected many painters in NYC; flood damage effected conservative, archival oil paintings and edgy post-modernist installations alike. Most artists will be hit with increasingly greater economic and personal hardship related to global warming in the near future.

Most painters understand that politics and art mix together like oil and water but isn’t there a point when the threats outweigh other concerns? Aren’t we living in a time when old rules no longer apply? Painters like Goya, Kollowitz, Picasso, Diego Rivera, Leon Golub and many others successfully merged formal painting concerns with humanistic concerns. Post-modernism rebels against modernist notions that art must stay inside strict formal boundaries. However when it comes to observational painting there is a curious paradox; I feel deeply connected to the natural world but disconnected to doing something to protect it.

Do you think it makes any sense for landscape painters to address issues that aren’t strictly formal and visual?

FH: If a landscape painter feels moved to turn his painting into a position paper on the environment that’s up to him. I feel strongly that whatever a painting does, or whatever purpose it serves, if it doesn’t achieve it through sensitive manipulation of visual, formal means, it ceases to be painting and instead becomes some curious form of text, propaganda, or pornography. That’s why painters work so hard for so long trying to understand color and the material nature of the media we use. Still, I can only speak for myself. I think there’s room for all sorts of motives and ideas in art. If someone has a particular genius for addressing environmental concerns and raising consciousness about it through art, I applaud that. Personally I’d rather write my congressman, or use social networking to raise consciousness, or take personal actions to minimize my impact on the environment than try to use my art as a political axe. Painting, for me, is a religious practice. Why would I want to mix it up with politics.

I went through the typical crisis of conscience that a lot of young painters feel about the seemingly self-serving nature of painting, but I got over it. Just think of what we’d have lost if Morandi had put aside his obsessions and painted anti-fascist paintings. What if Corot had decided that landscapes weren’t an appropriate response to the social problems of his day? We’re always asking what purpose art serves in society. We forget that Monet painted his giant water lilly paintings with WWI raging across Europe. Can problems get any bigger than that? Millions of people flock to museums to drink in Monet’s vision, or bask in the color rays of Van Gogh’s vision. Cynically we might say that it’s because the museums have turned artists into celebrities and profit from their marketing, but I still believe that it’s the unique power of those paintings, the color, the vision of the artist worked out in the physical material of the painting that fills a spiritual hunger that’s as real, and as important as the body’s need for food.

I think I’ve come to an even more radical assertion, however. I would argue that it’s actually the form, and not just the content, that is the political act. However seemingly innocuous or politically neutral they may appear in terms of subject matter, great paintings change how we see things, how we regard ourselves and our relations to the world and each other; a Matisse interior no less than, or possibly even more so than Picasso’s Guernica. Those altered perceptions are as much at work when we vote and push for social change as our more consciously held political opinions. Didn’t Cezanne say, “With an apple I will revolutionize Paris.”

So, in answer to your question, I would say that, at least for me, it makes no sense, as a landscape painter, to consciously try to program my work to raise political, ecological, or social issues. I wouldn’t even know how to do that. I’m still learning how to mix colors! I think Einstein himself said something to the effect that we’ve created problems from a level of consciousness which is incapable of solving them. Only a higher consciousness will be able to “imagine” its way out of those problems. At the end of the day, I believe that great painters, and artists of all types, are the visionaries that push the evolution of human consciousness forward. The feeling, intuitive Self – the subconscious, the unconscious, call it whatever you will – is where the higher truth is grasped, not the opinionating, ego-centric mind.

LG: What are you working on now? Any shows or events coming up for you?

FH: Teaching takes a lot of my time these days but at this time in my time of life nothing could be more rewarding than working with serious students. As for my paintings, since moving to Ohio I’ve had to come to terms with a completely different kind of landscape. For most of my life the Virginia landscape of my childhood has loomed large in my work. I never realized how strongly my identity was wrapped up in my feelings for that landscape, my friends and family, and my ancestry there that goes back practically to Jamestown. In many ways it’s been liberating to deal with a landscape that doesn’t evoke these primordial feelings. I’ve been working on a series of industrial ruins that I stumbled across coming back from a Thanksgiving break in Virginia, down in the southern part of Ohio along the Ohio River. I’ve also rediscoverd casein paint and have been working with that. This summer and fall I have my first sabbatical, ever, and am looking forward to seeing more of Europe and England and working on some new paintings for a show that I will have at the University of South Carolina next year.

Awesome work and wise words. Thanks Frank and Larry…I will slowly digest this and re-read in a few days. Your students are lucky to have you

Wonderful work. I really love the ascetic of these paintings. I need to take in what Frank Hobbs has articulated here but a few things immediately came up in my mind as I read this interview.

I am curious about his take on Italian painters. Where is Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese?

In my opinion how can you even discuss Italian painting, and painting at all for that matter, without looking at these great artists? Maybe this is a given. But I am left wondering about them in context to Giotto, Masaccio.

I also wish he would have elaborated more on why he thought the Caracci brothers ruined Italian painting.

Fantastic interview. Love the paintings. Love the words. Wish I could’ve had a teacher like him.

I’ve been looking at Frank’s paintings for awhile now, albeit from a distance, in repro, via Facebook or whatever. Nevertheless, I’ve found myself returning to them time and again. These are such intelligent paintings! Not clever, in a facile sort of way, but a real painterly intelligence operating behind every decision.

Bravo , Frank!

And thank you, Larry, for yet another fascinating interview.

I really admire Frank’s work. There is such a sensitive intuitive quality about them that keeps bringing me back to view them. Thank you for sharing his thoughts and works on this forum.

excellent ….as usual. I know frank’s work and Frank from many years of working together….he’s the REAL THING….A student once ask me who I go to for critique of my work….My answer was no one, but if I did there would be only two people…one of them is Frank Hobbs…one of the best eyes, best minds, and commentators about painting that I know off…

As a landscape (and animal) painter it was a great joy to read such a finely tuned awareness about painting and art, evoked in finely crafted sentences. I raise my hat to the artist and his expressive yet restrained work, and became an admirer on the spot. Thank you Larry Groff, and thank you Frank Hobbs.

Robin

Very impressive work, Edwin Dickinson would have admired this painter.The jSS seems to be in some ways an offshoot

of Lennart Anderson’s teaching. I mean that as a statement not a criticism.A small point,the titles for the works by Costa & Abbati are reversed.I see no reason that our reasons for liking & not liking various Italian painters need be rational.If one

teaches Art History(properly understood) then one should attempt to block out subjective tastes but it may be a serious

mistake for painters to do so.

Fantastic article. Really enjoyed the point of view.

I missed this one, and so glad to see it now. Thank you for the interview, and hearing Frank’s words about painting always makes me want to run back outside to look at things again…inspiring!

really enjoyed reading the artist’s thoughts. Very articulate. Must be a great teacher.

Please don’t take as a criticism but the paintings lag behind his knowledge. Not a bad thing. With his mind his eyes will catch up.

I had the pleasure to do a workshop with Frank Hobbs about ten years ago in Richmond, VA. He made a great impression on me and my work (I hope) at the time, and I truly enjoyed coming across this piece on your blog.

Thank you for sharing this interview and the outstanding collection of his (and others) work. Mr. Hobbs has continued to change (I started to write grow) in his work and I loved seeing these examples. I need a kick-start from time to time; this was perfect!

This is a wonderful interview… full of insight and wisdom. Many thanks to both of you.