(Please note: all images in this article show a very large version once clicked )

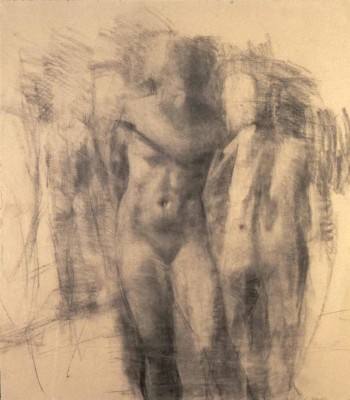

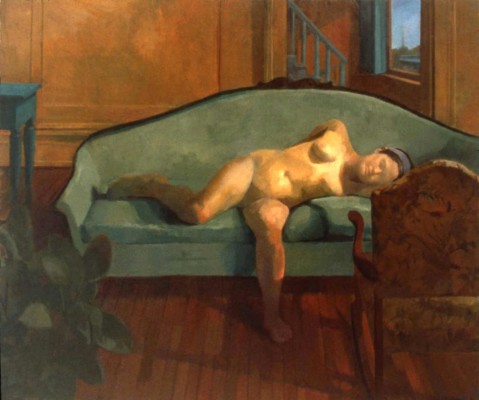

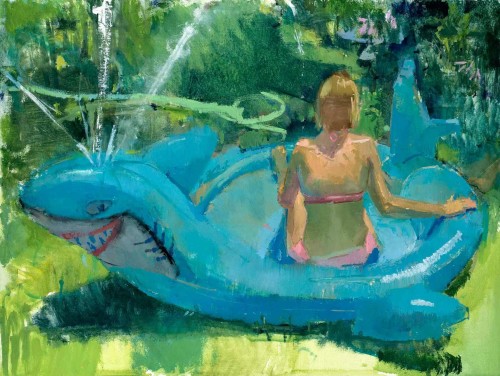

I was delighted to get a chance to meet Eve Mansdorf last summer in Italy where she and her husband Tim Kennedy lead a workshop at the JSS in Civita Summer Art School and Residency in Civita Castellana. I’ve long admired her paintings and was thrilled when she agreed to an interview with me over Skype and email. I would like to thank Ms. Mansdorf for taking the time to talk with me about her background, process and thoughts on painting. Eve Mansdorf is a faculty member in the Indiana University Painting department and an important figurative painter coming out of the tradition of Balthus, Edwin Dickinson, and Lennart Anderson. Mansdorf’s paintings and words here celebrate the continuing relevance of painterly representation and the visual poetics of paint.

Mansdorf has had solo exhibitions at the First Street Gallery, NYC and has been represented by Gallery Henoch in NYC. She has participated in numerous group exhibitions including: SoFA Gallery, Indiana University, Zeuxis: A Moveable Feast, Westbeth Gallery NYC, Lori Bookstein Fine Art, NYC, Eric Dean Gallery, Wabash College, Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, George Nick Selects, Concord Art Association, Concord, MA Hackett Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, CA. Her work had been reviewed by Mario Naves in the New York Observer (8/2005) and Jed Perl in The New Republic, 4/2005

Larry Groff: What led you to go to art school and become a painter?

Eve Mansdorf: It was not an actual decision; rather it was a process that evolved. I went to college with no intention of becoming an artist; it wasn’t even on my radar. I didn’t think that was something you could realistically do with your life. It wasn’t until after college that I started seriously taking art classes and once I started doing that, I got addicted to taking them and I couldn’t stop. Eventually I went to graduate school and I think at that point I knew I was in it for the long haul.

LG: You were a Psychology major during your undergraduate studies at Cornell University?

EM: I don’t know how much being a Psychology major really was a choice as much as it was a default major. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do when I was in college. I got a BS in Psychology and would sometimes tell people that yes, that’s what it was-BS!

LG: You studied with Lennart Anderson and Francis Cunningham, what was that like for you?

EM: Dick Cunningham’s class at the Art Students League was my first real painting class. It had an oddball approach. Cunningham had us crop pieces out of a set up, never painting the whole thing. The setup would have drapery that cut across the model in odd ways to obscure the fact that you were painting a figure. The main emphasis was on color-spot mixing with a palette knife, trying to get accurate shapes of color next to each other. I think this was taken from the way Dickinson taught painting. It wasn’t until later, after having been in other painting classes that I realized how unusual this was. Despite, or maybe even because of, not placing emphasis on getting the whole figure or getting proportions right it was a very good way to start. It immediately got you using a lot of paint and thinking in terms of relationships of shape and color as opposed to identifying objects.

It was during Dick Cunningham’s class that I was first exposed to artists like Edwin Dickinson. I eventually decided to go to graduate school at Brooklyn College so I could study with Lennart Anderson, whose work I really admired. I don’t think I necessarily knew at the time that Dickinson had influenced him. I just knew that I liked his painting. I had seen a portrait Anderson had done of Leonard Petrillo in a show at the National Academy of Design. There was a part in the painting where the angle of a hand met a corduroy jacket sleeve and it was just a magical moment of paint. There really was almost nothing there, just a few smudges of paint in the right places but everything was established–the texture of the corduroy, the shape of the hand, the strangeness of the foreshortening. Lennart’s main teaching strategy involved the idea of getting three points as a basis for drawing and he talked a lot about getting the location of things and striking the “right note”, which is also a color spot idea. He would say it was easier to move a location than a thing. Sometimes Lennart would paint on your paintings during his Saturday morning figure class. It was wonderful, if a bit frustrating, to watch him Lennart-ize your painting. Once he sat down at my painting and after struggling with it and sighing and groaning for a while he looked up at me and said, “Well I wouldn’t have gotten it into this state in the first place!”

LG: I can see where their color-spot teaching is still an important aspect of your work.

EM: Many times the first things you learn really stick with you, so you should be careful with what you first learn!

Also, part of the attraction of Lennart’s paintings for me, and Dickinson’s as well, is sensitivity to edges, the allowance for a come and go quality to the edges, that lost and found feeling to things. And there is the robust use of the paint itself, the paint being a critical factor in the making of the thing as opposed to drawing first.

LG: What more can you say about Edwin Dickinson in relation to your painting?

EM: I think for every generation of artists there is a Zeitgeist, a circle of painters that appear to everybody at one time. Many of the painters I came of age with also were attracted to Edwin Dickinson. There had been a Dickinson show at the National Academy of Design as well as a couple of shows at Hirschl & Adler. Many people including myself had seen these shows early on when we were first starting to paint. Dickinson was known as a painter’s painter and there was a reverence for him floating in the air. However, it wasn’t just Dickinson. Balthus was a big influence. I can sometimes see more of Balthus in Lennart’s work than Dickinson. There were also Lucian Freud, Antonio Lopez Garcia and Euan Uglow, among others.

LG: What did you do coming out of graduate school?

EM: I knew I wanted to get a college teaching job. I was convinced that I was going to need some other means of making a living besides painting. I wanted a job that would enable me to paint and that selling my paintings wasn’t likely to be enough.

I had worked at graphic design jobs before going to graduate school and it had seemed that every job I had turned into a full time job, which I didn’t want. I wanted a situation where I could spend most of my time painting. I started applying for university teaching jobs very soon after finishing graduate school but it took six years before I got the position I now have at Indiana University. One of my problems was getting some initial teaching experience, as the graduate program at Brooklyn College did not allow for teaching assistantships. I had various adjunct positions and teaching jobs including some with children in the New York City schools where I was a kind of visiting art program–I would drag all my stuff around on the subway. My jobs were part-time, which allowed me time to paint. I rented an apartment where the bedroom was my studio and I painted a lot and got by. It was a good period and, looking back, I’m glad I didn’t get a full-time, tenure track position right away, that I had that extra time in New York and was able to be exposed to so much great art and truthfully, painting in my bedroom at that point was just fine.

LG: You were making smaller paintings then?

EM: No, I was making huge paintings! They were my biggest paintings of all. 96 by 96 inch paintings, all I needed was a big enough wall. It was usually no small matter to get a painting that size down the stairs of a fourth floor walk-up.

LG: Did you have to take it off the stretcher bars and roll it up to get it down the steps?

EM: No, I tried to avoid that–you get never get them tight enough again. But I have had to saw a painting in half and fold it around a rug core to get it down the stairs. Or lower a painting between the banisters.

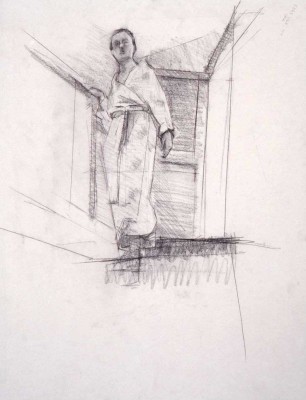

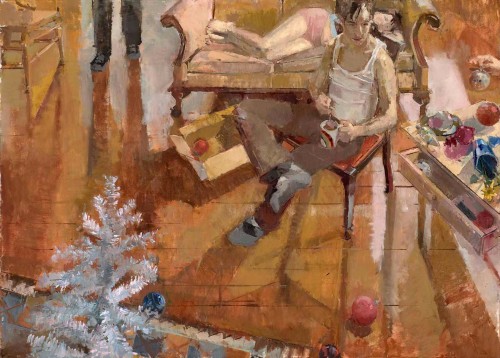

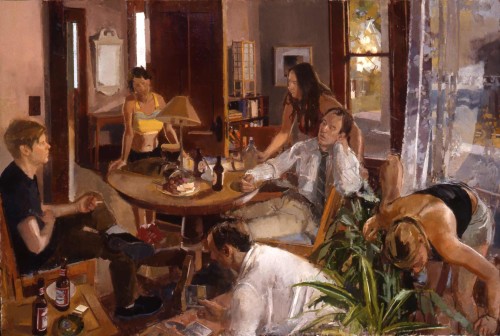

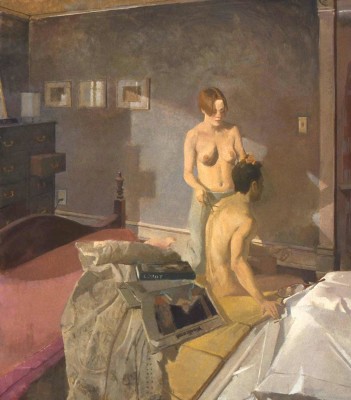

When I was in graduate school I mainly painted still lifes but the first few years after graduate school I concentrated on the figure paintings. I tend to paint things close to life size so my paintings got exponentially bigger very quickly, especially since I want to allow for an environment for the figure to be in. I have always been interested in painting the figure in a space, in a way setting a stage. The places I lived in were important as I used a lot of the architecture; I liked the moldings, the staircases. I also liked the evocativeness of a space–the “idea” of kitchen or bedroom and what can be dramatized there. To this day I have trouble working in a real studio space that doesn’t have that kind of architectural detail or connotation.

LG: I find it intriguing that you’ve combined observation with psychology. In the catalogue for your 2005 First Street Gallery show you stated…

“The two most important elements for me as a painter are the psychological situation I am trying to present which manifests itself as the mood or event, and the phenomenology of the painting that, for me, is its formal nature. In the first instance I am somewhat Freudian and in the second, Kantian. The more observational it is, the more engrossed I am by the experience of painting. The struggle between disinterestedness and grasping often characterizes the evolution of a painting for me. At the same time I enjoy the artifice of painting, the act of bringing into being something that is willed, created. I think of this as this psychological event of the painting.”

Do you think that there is a risk for observational painters becoming too involved with formal concerns and not thinking enough about psychological realms or the emotional presence of the painting?

EM: What I am saying in that quote is that I often want a tension between formal elements such as form, light, color and other elements that are more subjective and psychological. I guess the Freudian part is the psychological aspect of the painting. The Kantian part is the formal part but really what I am arguing for there is for the uselessness of art–the value of aesthetic experience as a thing in itself rather than as something that improves life in the community or edifies in some way.

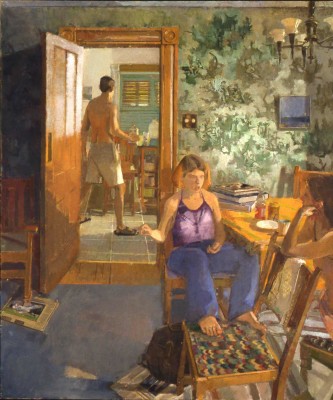

When you’re doing figure painting, one way is to paint the model as a kind of objectified form where the model sits and poses for you and you’re treating them a bit like a still life object. Once you move away from that and become concerned with creating activity in the painting, a social world, a contextual space, a psychological tension develops in the painting. It is inevitable in some ways and, as the painter, you have to manage the dynamic that is coming into being. You are starting to create artifice. Some people call this narrative.

Many observational painters are uncomfortable making that leap–they feel it is dishonest somehow. I am not interested in a really overt narrative. I find it too confining. But I am interested in creating metaphors and relationships between things that are not simply formal.

Often the real immediacy, the really engrossing aspect of painting for me is the activity of observation, putting my hand on the brush, the back and forth between myself and a motif and the sense of being in the moment, but it limits what you can do. For instance, you can’t paint someone running down the street or dangling from the ceiling. The idea of movement is difficult to deal with for an observational painter. It is an obstacle just to paint an environment that is not very close to your studio.

Many kinds of figure paintings I do or like stretch the definition of observation. There is a desire to get some other element that goes beyond a strictly observational moment into the paintings. On the other hand among my favorite paintings are those where someone is working from a source and not trying to embellish it, like Lennart’s beautiful portrait of Barbara S. You wouldn’t ask for anything more in a painting like that and I can feel guilty that I do need more. However, sometimes in observational painting there can be a kind of hemmed in quality and you wish the artist would interject something more than strictly looking at the source. When I was in school Lennart would sometimes tell me, “You’ve got to get the life class look out of your painting.” I think that’s true–you have to get past that classroom mentality in a painting, you’ve got to get ownership of it.

LG: That’s a great way of putting it. You have to find your own voice, sometimes that can come best out of direct, honest painting from observation. Of course you should also go beyond just making inventory or copies of what you see in nature. However, if the emphasis is just on the formal, visual concerns, like a geometric arrangement or color interaction; sometimes emotion and ideas are downplayed or eliminated altogether. However, I’m not sure this formalism is something still relevant or frequently talked about in today’s art schools.

EM: I think when artists went back to figuration in the shadow of Abstract Expressionism there was a need to justify doing it by insisting on the formal qualities of a painting and removing other kinds of content. It was like you were making a modernist, formal statement that was similar to an abstract painting. I think things have gone very far in the other direction, almost too far. Among the students I have now it can be very difficult to get people to talk about formal things, everyone wants to tell you about their childhood and other personal matters and to become so subjective that you actually want the formal stuff back in. There is always that pushing back and forth.

LG: They might have a great personal or political story to tell but sadly, all too often the paint and the drawing tells us a different story, which is that they don’t yet know how to paint. Many art schools today encourage art theory over practice, the narrative and emotional over the formal painting issues. Perhaps some teachers fear that studio teaching of painting fundamentals might seem like learning a trade or craft, and believe teaching painting should be on a higher intellectual plane than just learning about how to draw the figure or get good color in your painting.

EM: There’s a formal language to painting, there are certain kinds of grammars and if you have no facility with the language or craft it’s a real problem. On the other hand there is the danger of being over-taught. In some schools now there is the idea that you learn what you need in order to make what you need to make. But you can’t just pick up a brush and expect magic to happen. There is a learning curve. On the other hand, almost in reaction to the non-teaching that can happen, there is a resurgence of academies, where the teaching is stultifying. I think it is best and it shows in the work, when you are learning and having insights as you are making a body of work and you paint to the level you can at any given period.

I now put things in my paintings that I would have been aghast to consider using when I was in graduate school. I would have thought you shouldn’t put such a highly personal, kitschy and recognizable thing in a painting. At that time I had ideas about the “purity” of form. Recently I’ve been doing still life paintings that have superheroes in them, Wonder Woman and things like that, there’s definitely a narrative going on and I would have been very against that in graduate school.

LG: It wouldn’t seem serious enough? Didn’t Philip Pearlstein make some Superman paintings when he first stopped painting abstractly?

EM: It wouldn’t be serious and it was in really bad taste somehow. Lennart emphasized a kind of muteness that could be evocative. Sometimes when I start putting a lot of crazy things in my paintings and cluttering them up I wonder if it isn’t a bit of a rebellion on my part against his sense of reserve.

LG: Post-modernism has opened up different ways of working and subjects that were previously shunned. This is a good thing don’t you think?

EM: Yes. For me the allowance for the inclusion of pop culture, nostalgia and sentimentality have been liberating. Humor and irony are interesting and do not undermine the seriousness of the effort. I like visual puns. I am also interested in the idea of a collaged together kind of painting. I think the rigors of Modernism can have a slightly fascist quality when taken too far.

I usually wonder at some point during the genesis of a painting if what I’m doing is just too stupid, too sentimental, too garish, etc. I used to be afraid of these moments, now I see them as good, self-questioning stages to go through–necessary even.

LG: Did you ever have doubts about choosing your life is a painter?

EM: Before I went to graduate school I think this was the continual question- should I do this or not. But once I went to graduate school I had a sense of commitment–no looking back. This is it; I’m going for it. Maybe because it had been such a difficult decision, I didn’t really question it afterwards until maybe five years ago. I was suddenly having a lot of doubts. I guess I was having a painter’s midlife crisis. That was when you had originally asked me for an interview and that was part of the reason I declined at that time.

One of the reasons I didn’t want to do the interview then because I wasn’t sure about what I thought at the time. I was wondering is this something valid, do I want to spend all my time doing this? Also, maybe it was at a point where I was feeling that painting was in a beleaguered state and I wasn’t sure about the painting world itself- if painting mattered in the way that it should matter or the way that it had mattered to me. I was really questioning painting as a form. I think many painters go through this at different points. However, I think I’m getting past that now.

LG: So what are the answers to these questions? There are many of us who are still asking and wondering?

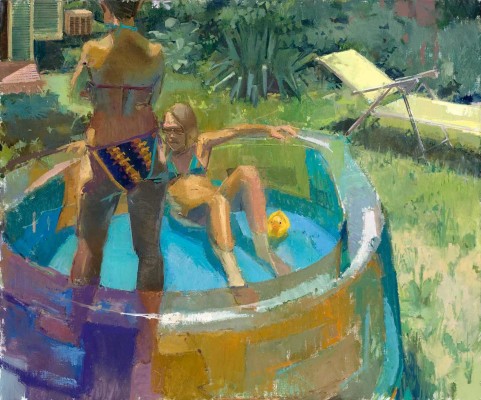

EM: I had never experienced any kind of painting block or lack of wanting to move forward in my work so it came as a shock to me. I think partly I needed to change some of my ways of working. I had been using models a lot. I generally had a whole crew. But the people who model in Bloomington tend be college students and I was starting to find it difficult to relate to them and use them as subject matter. They are all just too young.

I think maybe if I could have found a whole cast of 40 and 50-year-old models it would have been great. Recently I have gone back to what I was doing out of grad school when I couldn’t afford to hire models which is to use a video camera, now a digital camera, and myself and a boyfriend, now my husband, Tim. I paint off a TV screen and from life and I kind of collage it all together in the paintings.

I think my paintings have always reflected the stage I have been at in my life and the nature of my relationships, particularly with men. Mark Greenwold has a quote that I love, which he got from Donald Antrim, “When you’re dealing with psycho-sexual anxiety, you never run out of material.”

LG: Depending on what level of realism you’re interested in or the level of observation you pursue; working directly from the model might become less important. Not being as dependent on a model might free you up to focus more on the narrative, the composition, the paint surface and such, even though it might also limit your abilities to get the naturalistic light, skin tones or a particular gesture and anatomical shape. Art history, of course, filled with examples of great figurative painting done without live models; like Goya or Michelangelo who I understand painted more out of their head or from drawings than from life, does that interest you or are you after something different for painting and you really want to have your paintings grounded in looking?

EM: I do want to have my paintings grounded in looking, in some way. However, I tend to mix it up, it doesn’t all have to be in front of me in one piece. It can’t be actually. However, if I’m in the studio for too long without something in front of me to look at and respond to I tend to get bored; I just don’t want to be there. It’s essentially a visual experience for me; I don’t know how people do it, to just paint out of their heads. The great “masterpiece “ painting from art history does present itself to me as a challenge. Many artists today want to disavow art history but I just love certain paintings too much–they haunt me.

LG: There is openness, a breathable atmosphere that envelops form in your work. Some of this seems to stem from how you orchestrate the edges. What things do you think about with getting the feeling of air in your paintings?

EM: Early on it was a very conscious thing to try to get air in my paintings. At this point it has become intuitive and I can’t help it. With still lifes I would set things up to make that happen. I would group things so that objects would merge into each other and then, in comparison, other things would appear more distinct. So there is a kind of seeing atmosphere and figuring out how to paint that atmosphere as much as trying to paint the objects themselves. It’s like painting the light as much as you’re painting the object. Painting the immaterial aspects of what makes the thing be there. But with the larger figure paintings there is a way I’m moving the painting around for quite awhile during the process of painting it, so it’s literally open in a certain way for a long time and maybe parts of it don’t ever completely close up. I’m still pushing it around when the painting is just about finished. Also I do a lot of removing–scraping and sanding–and then reasserting what is there.

I always seem to need very fluid edges in my paintings. I have fought it sometimes, trying to be more Northern in my approach–more crisp and linear; but it never works out. I think I once read a quote from Gerhard Richter where he talks about how he tries to paint paintings with hard crisp edges but in the end he always goes back to the blur. I guess I kind of have that problem.

LG: How do you go about starting a painting?

EM: I usually spend about three years producing a body of work. It seems to take about a year for a body of work to gain a certain momentum, to develop a theme of sorts. That is something that started in graduate school. Actually one of the best things about graduate school was the sense of working in a time frame. A kind of arc that now seems Pavlovian. Often the first paintings can be difficult to get off the ground. Either it feels like there are too many possibilities or there is no clear reason why I should do anything in particular. But then when things are going well one thing can lead to another. I am usually working on a couple of still lifes and two or three figure paintings at a time. The still lifes often reflect something that is happening in the figure paintings or vice versa.

I don’t start with any sketches or preliminary drawings. When I begin a painting I often keep the paint kind of thin and the edges very open as I figure out what is going on. I will keep the composition fluid and malleable for quite a while. I do this by painting things in a blurry way, massing large shapes that stand in for things, and as Lennart would say “painting locations as opposed to things”. With the figure paintings I will usually get attached to something–the gesture of a figure, the color of something and I begin to work off that. Very often what got me started in the first place has to be removed later on. The paintings can change drastically as they go along, sometimes until quite late in the process. It can alternate between being frustrating and exhilarating. With still lifes the set up is very important–it is, in a way, the sketch. And as I am working from something in front of me, there is more of a sense of direction right from the beginning. I guess somewhere in the back of my mind I am committed to this idea of painting as a process of ‘finding” and “finding out” as opposed to executing something. So I am amenable to a seemingly very disorderly process.

LG: What more can you tell us about your process?

I use palette knives and soft brushes. I often mix and apply paint with a palette knife and move it with a brush. I sometimes start the big paintings with large Chinese bristle brushes that you can buy in the hardware store very cheaply. I don’t even wash them. I just throw them out at the end of the day. I love painting with them but the problem is that they shed hairs. I am often experimenting with a new color palette. I will have some idea about color–whether to restrict it or open it up–and my palette will reflect this. Lately I just use cadmiums, ultramarine and cobalt blue, alizarin crimson and titanium white. I have banished earth tones, black and oddball colors. But I used to use a lot of earth tones and I love trying oddball colors so that will probably change again. I am opposed to flake white because of its toxicity, but I understand some people believe in it as a kind of alchemy-that you just can’t paint it without it. I have been using real turpentine lately-so there goes my idea of being against toxicity. I had a lot of problems last year experimenting with driers like Liquin and now I am back to an old medium I used to use which is thirds of Venice turpentine, stand oil and regular turpentine.

I will often sand and scrape my paintings and do things to mess them up as I am going forward. It is not a linear process that moves straightforwardly toward completion, but more, if I’m lucky, a two steps forward and one step back kind of movement. Sometimes the paint or the surface becomes intractable and needs to be resuscitated!

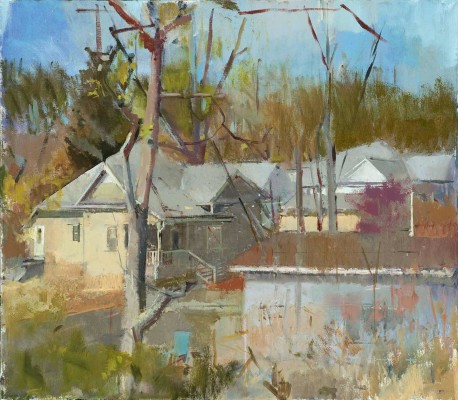

LG: You bought a house to use for your set-ups and models, can you tell us something about this?

EM: When I first got tenure here, I bought a house to paint in. This had always been a fantasy of mine–to have a real interior to paint from and to have everything all together in one place. I had been doing the large figure paintings in my studio but I was creating interiors that were based on where I was living–so essentially I was painting the space from memory. For instance, when I first moved here the house that I lived in had French doors between the living room and the dining room. I thought this created a great motif. I would use the memory of the French doors while painting a posed model in the studio. I also bought a paned glass door at a junk shop and leaned it against the wall in my studio as a reference. But I couldn’t really just see the figure standing in front of the French doors. I was always making things up and trying to figure out how to make things “work” in the paintings–what the scale of things should be, where the feet should go, etc.

Buying that house was like getting a life-sized dollhouse or a studio set to paint in. Suddenly it was all in front of me. Things that had seemed like enormous problems of mental construction suddenly became straightforward acts of observation. I had a wonderful 4 or 5-year period of painting in this house.

LG: Was anyone living in the house?

EM: No, it was just a house; I was using it like a rented studio. It seemed like an extravagance but in Bloomington it’s actually cheaper to buy a house than to rent something. I sold it after I felt I was done with that body of work and didn’t lose any money. I eventually tried doing this a second time with another house but it never really had the same kind of magic as that first time did. The second house I bought to paint in is actually where I live and work now. Eventually I found that I not only wanted a real space to paint in but that I wanted to paint real life–the living room as it really is used, etc. Of course then your whole living room ends up taped off and you can’t actually live in it anymore!

LG: I’m curious if you’ve looked at Paula Rego’s painting much? It seems like there are some affinities, especially with that psychological edge and with the interaction between the figures, like with your painting of the woman cutting the man’s hair. That seems like a Paula Rego moment.

EM: Oh yes, definitely. There is a painting of Rego’s from a series called Departure where a woman is combing a man’s hair. A very Balthusy-type painting.

LG: I think she also made one of two women undressing a man.

EM: Yes, that is a painting called Family. I think they are actually dressing him. I love that about Paula Rego, the intense use of the bodies to act things out. She has such good poses. I love the paintings of the women as dogs, very visceral–I love that.

LG: I don’t know how she works, if she uses models but I would imagine it wouldn’t all be in the same space at one time.

EM: I have read some things about this–I think she uses a model a lot, she has a woman who poses for her, who I thought was her, but is actually someone who is a model that I think physically resembles her. She builds many of the props for her setups; I went to a show of hers where she had all the props in the show, like theatre props. There doesn’t seem to be an orthodoxy about it though; she’ll use the stuff she needs to–that is part of what I like about her work–the sense of improvisation in the face of necessity.

LG: You’re mentioned earlier about leaving a painting open until the last minute. How do you decide when the painting is complete and do you ever go back into work into older paintings?

EM: I will work on a painting as long as it’s still in the studio and hasn’t been shown yet. It’s always up for grabs. My painting process at this point allows for that to happen. I often start a painting and really go at it for a while but after several months reach this point where I get stuck and don’t know what to do next or maybe I just hate the painting and don’t want to look at it for a while. I will let it sit while I work on something else. I wouldn’t have done this earlier in my painting life, I might have been more destructive, but I now realize it can be a fruitful thing to leave it just sitting there. I will start something else and it usually seems like after about 6 months I’ll turn around one day and get a new idea about it and start painting it again. However, once I’ve put the work in a show or it’s really been seen in a public way I can feel detached from it. Even if it comes back to the studio; it’s almost like it’s not mine anymore, even if I realize things I should have done.

LG: Is observation a point of departure for you or the whole reason for being there.

EM: It’s both. It’s a point of departure in that I’m not completely tied to the observation. I will mess around with it if I need to.

LG: Being engaged with the painting is maybe like having an experience with the world through paint, not just that you’re trying to recreate the world in your head, it’s like you’re a participant with the world. Does that make sense?

EM: I’m not sure I follow you.

LG: When you’re painting from life you’re responding to something. It’s not all internalized, instead there’s an interaction with looking at the outside world, an experience. This can result in a loss of the sense of self, with this intense process of looking and responding; it becomes this all-consuming experience.

EM: Exactly. That’s very true. I think there are two distinct experiences or attitudes I tend to want to have. One is the “in the moment” Zen-like sense of just being there and responding to something it front of me–trying to get it in some way. In that moment my brain is almost completely not verbal–it is just saying things like, “…no move it to left, no redder, yes that’s it…”, etc. And there is great pleasure in that. It is probably the real “turn on” of painting.

But there is also a pleasure in standing back from the painting at the end of the day, sitting there and thinking about the painting, what’s working and what’s not working, what is being suggested, what I might title this painting–the cigarette moment, although I don’t smoke anymore; this is when I am more removed and getting distance from the painting and trying to figure out what the painting is trying to say. I’m being an audience for my own painting. Both experiences are a way of stepping outside myself.

LG: Do you think there is a difference between beauty in nature and beauty in a painting?

EM: A Rembrandt self-portrait with his bad teeth is an exquisite, beautiful painting but he doesn’t look beautiful. I once showed a reproduction of Antonio Lopez Garcia’s painting of a woman in a bathtub to a friend of mine and I said, “Isn’t this beautiful? ” and he looked at it and he said, “I don’t know she’s kind of dumpy.”

LG: Many people and even artists don’t get observational painting, dismissing it as outdated or perhaps lacking intellectual rigor and substance. What might you say to help them get past this bias?

EM: Open your eyes! I think the problem is there’s not enough critical discourse about observational painting. Of course not all observational painting is good, just like not all conceptual art is good, not all abstract painting is good, etc. Some of it is wonderful, some mediocre and some of it is terrible. The problem is when it’s dismissed out of hand and not looked at critically and when people aren’t being discerning between what makes this a really good painting and another one not. I wish more people would have critical thoughts about what makes an observational painting good.

I also think that there can be such an emphasis in criticism on what’s verbal and very often observational painting defies verbalization, it’s not easy to put a visual experience into words and it may seem less interesting to a writer.

LG: Does the lessor status and attention given to observational painting in the art world ever discourage you?

EM: Yes, of course. I don’t think it helps. I just wish there could at least be more discussion about it because I think it would be nourishing and interesting to people who are doing it. I’m always excited if there is someplace where people are having a lively fight or discussion about observational painting. It helps me think about it for myself, what I think is good or not good.

LG: Do you have much going on at your school? I’ve often heard that Indiana University’s Painting program is a good place for people wanting to study figurative painting. So I would imagine there’s a lot of support there.

EM: We do tend to attract a certain group of painters who want to have that discourse, and because of it those types of discussions evolve more readily. But it can go in many different directions here, we’ve had classes of students who are very rejecting of the idea of painting from life or of painting from any tradition at all! Or of painting! It was similar at Brooklyn College too. There would be years where people would be very interested in Lennart’s ideas about painting and then other years where people might reject his ideas. He was always there as a kind of fulcrum and you had to react to him. In a way, that’s also what Tim and I are here at IU.

LG: Do you have other faculty members that are your opposites? That are conceptual or doing other things that are completely different? Or is it mainly figurative?

EM: In the Painting area there is an inclination towards figuration as well as for the painting to be about paint. The art department is large and is broken down into distinct areas such as Sculpture, Photography, Ceramics, Printmaking, Digital Art, etc. These areas have diverse points of view and emphases which broadens the conversation. In many studio art programs people are now doing videos and calling it painting, and we do have some of that, but not without question, and there is an attempt to maintain an idea that painting in the end really needs paint. So things float around a certain parameter. There’s Tim Kennedy and me. Tina Newberry teaches here-she’s a wonderfully eccentric figurative painter- as well as Caleb Weintraub-he’s a figurative painter who uses mixed media, video, installation and technology in his paintings. There is a rotating visitor position. Right now Gabe Phipps, who is an abstract painter, is our visitor. Painting at IU isn’t all going in one direction, it’s not all observational, there’s a kind of continual challenge to the idea, but then the observational painting also reasserts itself. Which is how it was when I was at Brooklyn College.

LG: I have a quote that I thought you wrote, regretfully that I’m unable to find, anyway someone, maybe you said; ‘painting should be less about an art object to work on and more as someone to attend to or a place to live in’. What can you say about this idea and what thoughts do you have about bringing life to a painting?

EM: Well I think it’s a great idea, even though I don’t remember saying that, I would love to have said it! I do think that is the way I feel when I’m very immersed in a painting. It’s like a personal relationship in my life. One of the reasons I paint really large paintings is because they are these big things that cannot be denied. Once I’ve started a big painting I know I’m going to make something out of it and finish it. Although I love other artists’ small paintings, especially when they are very realized, with my own small paintings, when I get to a frustration point, I can too easily just push it aside.

Once I’ve started one of the big monster paintings it’s like any other kind of relationship, it’s got it’s ups and downs, and I really have to deal with it, argue with it and make up with it–it’s a very immersive involvement. I have to carry through with it and see what I get at the end. That is one of the reasons I am not dogmatic about the idea that it has to be from one particular source or follow any particular rule that I might have in my head about what painting should or shouldn’t be.

At a certain point the painting has a kind of existence. It just needs certain things, it makes its own demands. That’s exciting. Sometimes when I listen to lectures by fanatical movie directors who have gone to great lengths to pursue a project, I can relate to it as a painter; this fanaticism about wanting to see your ideas realized.

Wonderful interview Larry, and thanks for the wonderful paintings, Eve. Nicely articulated thoughts on your work process…it was good to hear about your intentions, memories and doubts, too. It seems that you and your colleagues have created seriously fertile ground for really good painting to flourish at Indiana University. Much needed in today’s art climate…Bravo!

Fantastic interview, Larry! Eve, your paintings are very liberating, thoughtful, perceptual and fresh. I appreciate your articulate thoughts on the relationship between observational, abstract and conceptual painting – you speak to things I’ve been mulling over. And thank you for speaking about the two distinct pleasures of being immersed in the work and the standing back, observing it. Another, Bravo!

This was a wonderful, absorbing interview., with beautiful, inspiring work, full of surprises and psychological depth, as well as formal qualities that continually moved me to look more and deeper at the paintings. Thank you very much.

Eve,

It is so interesting to read your thoughts about painting and being a painter.

Bill

Thank you for the wonderful interview Larry. Eve, I’ve digitally admired your paintings for a long time, hopefully I’ll see one in person eventually. It is a blast to see the studio/space pictures. Great interview, I’m glad you came around.

What a great interview; and thanks for posting the high-resolution images… I’d enjoy seeing the work in person sometime. Always exciting to see work that mixes working from observation, with a distinct internal vision that is strong enough to break through consistently.

Philip Frey Thank you for sending this discussion. I’ve made many notes that I can consider and use, hopefully. Loved seeing the paintings along with the discussion. Loved hearing about fluid edges vs crisp and linear, the psychological and the observational and the zen moments and then the critique, A wonderful gift to other painters.

I like that post. I am also a painter and a blogger..check my article https://www.paintandpainting.com/the-broken-column/