Larry Groff:

You’ve touched, actually, on this question, on some of the other things, but you might find something new to say here. My question is, in many of your earlier paintings, many times I see a brighter, more naturalistic feel. You would often include more specific, recognizable forms, such as houses, barns, more obvious signs of human presence.

Your more recent work, especially with the Wildfire series, your work takes on a more abstract, expressionist and darker tone. I can’t help but wonder what the underlying narrative is with these wildfire and ice flow paintings. I imagine them to be at least, in part, having ecological, as well as psychological overtones. I was hoping you could speak about that.

Eric Aho:

That’s a really good question, and one that I’m speaking a lot about, right now, as I’m meeting people in the gallery in New York. I was there over the weekend, and visitors wanted to know specifically about the wildfire paintings, if they’re about the California wildfires.

And, for the most part, they’re not. I’ve never witnessed a wildfire before. The series of fire paintings that are up and exhibited right now grow out of a single painting by Rembrandt, which is the Rest on the Flight into Egypt. It’s the group of figures around a bonfire, a campfire, with this really wonderful, warm, comforting light, with a full moon breaking over a ridgeline, a real dark, black, that space that one just can’t pass through. And beyond that ridge that is this gorgeous, crystal, silvery moonlight. I’ve just been fascinated by the contrast of those two sources, types of light

Rembrandt van Rijn Rest on the Flight into Egypt 1647 oil on canvas 13 x 18 inches

I tried to make that painting in my studio. I tried to copy that Rembrandt painting, both from memory and from little postcards, and it was just an absolute failure. I put that project aside for a little while.

And then one day, I’m driving out of town, running some errands, and the local farmer, just on the edge of town, is burning brush. It’s late in March, the moon is rising, and the smoke from the brushfire [is] mixing with the clouds. And in that mix I see that Rembrandt painting, right there. All of the conditions of it are so right.

I set up immediately, and I started making some paintings, on sight. Those small plein air canvases led me into a group of larger paintings, in the studio, of a contained brushfire. And when I had kind of worked through that, a little bit, I might have made six or eight 50 inch paintings, I then started imagining that fire, sort of just stepping out of its bounds, a little bit, and going out of control. It’s not overtaking the landscape, so much as kind of seeping into it.

And I realized that the paintings became more about imagination and about the course of imagination, than they were about actual fires. I used the fires as that classical reference to imagination, and I just ran with it.

Red Winter 2008 Oil on linen, 50 x 80 inches

It was also a way for me to create a personal metaphor for clearing the landscape, the classical landscape that I had been drawn to, and which t I had been painting myself. I literally burned it down. I didn’t know that when I was starting the project; but as I was in the middle of it, I realized these trees, these white birches and these other spruces that are toppling over are essentially like pillars of classicism that I’m trying to get beyond, or do something different with.

I’ve never experienced a wildfire, and I have tried very, very hard not to subject myself to any photographs on the subject. Of course it’s in the news, and it’s a very current issue in the news, certainly for everyone in California. I read the news, but I try not to look at the pictures.

Very recently, a friend sent me some jpegs — he had taken photographs of the Santa Barbara fires, on a trip of his last year — and I had five or six jpegs on the screen, and I scrolled through them. One of them was of an abandoned swimming pool, in this perfectly manicured, California — what comes to mind is a Hollywood-type home — modernist house, just a perfect existence. This pool, it’s abandoned and still lit, glowing green and right behind it, ten yards away, is this massive wildfire.

I saw that image, and I said, “Oh my gosh, that’s exactly the kind of contrast and extreme that I’m interested in approaching with my paintings.”

So, I closed up the email. I went upstairs into the studio the next day or that weekend, and I made a pool painting. It’s the first painting I’ve ever made, which I can say is made in response to a photograph. I changed the kidney-shaped pool to a rectangle, for my purposes, hoping to create a counterpoint to the ice cut painting.

California Wildfires Oil on Linen 48 x 52 inches

Because I was also thinking, Well, the black ice cut, has this black void, and I’ve made three of these now, and I hope to make a series of about ten. But then I realized, Well, why does the void have to be black? And in that pool painting, I realized that the void can be ethereal and light-filled, and the blackness can surround it.

So there’s something about the wilderness taking over this perfectly situated domestic symbol, the pool, which is also quite an American symbol, in some ways. So those are things that are presenting themselves right now. So the pool paintings really do have to do with the California wildfires, to a certain extent.

Just coincidentally, I was coming back from a trip to Colorado. This always amazes me, but I was sitting on the plane next to a young woman who was traveling to North Carolina, where we were switching planes, and we didn’t say much during the flight; but at fifteen minutes before landing, you have that inevitable conversation with your fellow passenger. And it turns out that she’s an urban planner, and her particular field of expertise is wildfire management. She’s a national expert on both wildfire prevention and wildfire planning. And she’s employed by the Florida state government at the moment.

She shared her thesis papers with me. They are a bit technical, beyond me really, but there’s a narrative that runs through them. I’m absolutely fascinated by them. So I have kind of opened up the lid on further investigation into the actuality of the wildfire. But like I said, they’re still about an experience of painting, particularly, and that gets to one of your previous questions of, the landscape as a point of departure.

LG

So, this is always a hard question to get into in depth, but, I just thought I would ask you, who [are] some of the past and contemporary landscape painters that most excite or influence you?

Eric Aho:

Well, that is a tough question. You specifically asked about landscape painters. I’m thinking, Well, gosh, I don’t know. Do I know any?

But I am primarily looking at figurative work. I’m obsessed with Rembrandt, obsessed with understanding and getting to that. From Rembrandt, I even get into the English painters, like Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud, both of whom are heroes of mine; and Frank Auerbach, in particular. These people are in their eighties, now.

LG

Well, Auerbach did a number of landscapes, as I recall, right? I remember seeing some cityscape, landscape imagery …

Eric Aho:

Yes, right. And he is a particularly good example of the landscape that maintains that sort of fleshy, gritty, figurative human experience. They’re not pictures, so much, as they are things. [Laughing]

And then there’s the painter Jenny Saville. I think she is interesting. I’ve become really curious, lately, about Cecily Brown. She’s making paintings about figures having sex in the landscape, they are built out of a just some kind of mush of paint, but there’s something very joyous about them. There’s something very physical, very aggressive, very big; but naturalistic too, to a certain extent. I find that really interesting. In the end, however, they are formless.

You mentioned Antonio López Garcia. I was struck by the recent exhibition in Boston, sort of the way one’s struck by being in the presence of — well, one of my visits was with George Nick, and I said, “George,” I said, “I’m having a hard time taking all this in. I’m actually feeling a little bit queasy,” because I was having such a varied and excited response to it.

“Do you know why that’s happening?” he asked. “Because you’re in the presence of true genius.”

I think that’s undeniable, in his case. That’s very, very exciting.

A painter like Andrew Wyeth, everyone has such mixed feelings about him. I admire him. I know he passed away recently. I admire his commitment to his subject, and his commitment to both the landscape and his figurative subjects, immensely. He spent his entire life chronicling these places and these people. Like López Garcia, a deep, deep commitment to the slow development and slow unraveling of the painting process. But it’s Wyeth’s detail that I find excruciatingly hard to take, but I think underneath all that detail is an armature of abstraction that’s really exciting.

And for that reason, I see him standing back-to-back, in a way, with someone like Ellsworth Kelly, who is a minimalist, abstract painter. Where Wyeth is kind of an anti-intellectual, Kelly is definitely an intellectual in his work. But his abstraction, to me, grows out of a naturalistic and observed experience; a shadow on a wall, the edge of the curve of a plant — all of these things add up to his interest in abstraction.

So those are painters that I look at.

There’s a young Canadian painter. He’s kind of working in too much of a New York Chelsea kind of style right now, for my taste, but there’s something about his attitude toward the landscape that I find interesting. His name is Kim Dorland. He makes statements to the effect that he’s interested in the legacy of Tom Thompson.

Do you know Tom Thompson’s work, the Canadian painter?

LG

No, I don’t, or the name doesn’t ring a bell, anyway.

Eric Aho:

[A] painter who died very young, but worked from about 1907 to about 1917. Look him up. They are about the best examples of an expressionistic, plein air, direct experience painting ever to have been achieved.

Tom Thomson Canoe and lake, Algonquin Park 1913 oil on canvas laid on panel, 6 x 9 inches

Eric Aho:

I mean, so much of all my work has been built on the experience that Tom Thompson puts forward in his painting, and I say that unabashedly. I’ve tried to digest each and every one of his little paintings.

He painted in Algonquin Park, Canada just after Cézanne’s death, 1907 to 1917. [He] wasn’t fully aware of Cézanne — well, knew about Cézanne, might have seen some things in Toronto or Chicago — but for the most part, he was just working independently, without influence. And remarkable things happened, and his life was cut short by a canoeing accident.

So here’s a young painter (Dorland) who’s over influenced by fashion, but underneath that, I can still see that he’s got some solid core ideas, that are very exciting. But I think you’ll see what I mean if you look him up.

Kim Dorland.RIP Tom Thomson 2009

Then there are certainly slews of others. It’s a daunting list. I guess I look at so many things, and so many things excite me.

LG

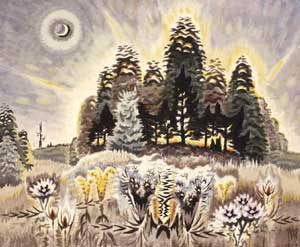

In California, I was excited to hear there’s currently a big landscape show of Charles Burchfield’s work, watercolors, who I think is very interesting, I would think to you, because he also is painting outside, but had a number of interesting, abstract points of departure from his work outside.

Charles Burchfield For the beauty of the earth 1959 Watercolor and Charcoal 33 x 40 inches

Eric Aho:

He internalized that landscape so closely and so personally, and I’m very excited about that show. I’ll wait and see it when it gets to New York, unless I have a chance to get out to California in the next couple of months.

LG

Well, if we have any wildfires out here, you’re welcome to come paint.

Eric Aho:

[Laughing] That would be great.

And I’m also really excited because the gallery in New York represents the Burchfield estate …

Eric Aho:

… and they had a hand in organizing that show. Bridget Moore, the dealer hasn’t ever said this directly, but I like to believe that one of the reasons that I fit into that stable is that she sees I may have some relationship to the Burchfield attitude towards the landscape.

There are so many people working with the landscape in remarkable and varied ways, but Burchfield —but I feel so close to him, much the way that I do Tommy Thompson or Frank Auerbach. I think there’s something kindred in that attitude.

And coincidentally, Burchfield was also very much of a Fennophile — a lover of Finnish culture.

Eric Aho:

I spoke with Robert Gober about this, a little bit. He’s the curator for the Burchfield show at the Hammer Museum. And Gober wasn’t aware that Burchfield was so deeply enamored with Finnish culture from music, poetry and architecture, and also through meeting the Finns who lived in upstate New York, and who worked in the mines and various other industries.

He gathered a sense from the national music, from Sibelius, in particular, that the Finnish sense of nature, which is mysterious and engaged and full of imagination, in a way eerily similar to Burchfield’s own unique work..

LG:

I can see that.

Eric Aho:

So I would venture to guess that there’s a lot there that could be unearthed with a bit of research. His interest in the Finnish Culture gives me great insight into his work and his person.

LG:

Last question. Do you think landscape painters — or I should say, really, painters — can or should speak to the many environmental issues that confront us? Is this something that interests or concerns you at all?

Eric Aho:

Yes and no. A student asked me this question, after a lecture recently and I said, “You know, you would my ice paintings were about global warming, and the fire paintings were about the California wildfires, and the change in the environment, and the impact on the environment, and all this.”

And I said, “Well, I’m fully aware that all of that’s happening.” I read the news, and I pay attention to the changing — even the small aspects of change around me here — winters are a little bit different than they were fifteen years ago. I’m no scientist, and I’m certainly not an activist. I don’t think painting really is the vehicle for that, any longer.

I’m happy that the paintings of the wildfires may draw some attention, or draw some parallel to what’s going on in California, if it increases anyone’s awareness, I think that’s only a good thing. But I think other mediums now: film and video and photography are so much more immediate and digestible, publicly, that I think those are the greater mediums for activism and drawing public attention to these events.

Painting is such a quiet, long-term pursuit, it doesn’t function in quite the same way as it did for Daumier and Goya and artists like that; although, an artist like William Kentridge certainly has this tremendous activism in his work, and it carries a tremendous impact. But I dare say, his audience is still pretty limited to those who follow art.

So, yes, I think it’s important for the painter to reconcile his or her own personal feelings about that issue, and be fairly clear about it; that yes, I’m here to make a message in this body of work or in this painting or in my life’s work. There’s Leon Golub and Nancy Spero who are famous for that.

Or you just accept that you’re doing something very different, and it’s okay to be involved in purely formal concerns, even while California is burning to the ground.

Eric Aho Fire Three 2007 Oil on linen, 50 x 70 inches

LG:

Well, you look at an artist like Fairfield Porter, and his work seems about as apolitical as you can get, but yet, in his personal life, he was a flaming, radical environmentalist.

Eric Aho:

That’s right. That’s right.

LG:

I think he made a lot of contributions, financially, to groups and other parts of his time, but the painting didn’t seem to make sense to do that. Unless it was the earlier work he did, I suppose.

Eric Aho:

Well, I agree. I think it’s important to do what you can do. Some people contribute to political causes. I mean, we each have our philanthropic concerns we give to, or we don’t. And everyone’s free to make those decisions.

The paintings that I’m making, the ice and the fires, they’re about extremes of imagination, more than anything else, and I’m really interested in how far an individual or how far, particularly myself, I can push my imagination. What are my limits?

I’m not saying they’re very great. I’m just saying that I’m interested in that point that we can’t go beyond, in a way, and the fire and the ice mark those kind of lines that you can’t pass.

Hopefully, those keep expanding, for myself and an audience, but I am aware that we all have limitations, and certainly painting is about limitation.

Audio Podcast of interview (approx. 1 hour) – right click to save to hard drive

[podcast]http://eric-aho-interview.s3.amazonaws.com/ericaho.mp3[/podcast]

Interview with Eric Aho – Part One

Interview with Eric Aho – Part Two

Another great interview, Larry! Thanks so much. Have been familiar with his work for a while, but great to get some background on his thoughts and process.

Larry, thanks so much for doing this! I’m so glad I read the interview and took a deeper look at this work which I am finding to be profound and inspiring, and somehow, exactly what I needed to see. I’m going to go catch this show before it closes. thanks!

Thanks Jimmy.

I envy you Jade if you get to see his show. Sadly I’m currently stuck on the wrong coast for this show. Glad you liked the interview.

Today I was visiting a friend of mine. I talked about your blog, how I connect to the artist, artwork and comments. Your interview with Mr. Nicks and Mr. Aho are both extremely interesting, informative, thought provoking, motivating… Thank You!

Myself a fellow painter had the pleasure of meeting Eric Aho by chance at one of his exhibitions in Chelsea a few years past.I admire all of Ahos work, but by far find the most engaging those pieces which meld more traditional painterly concepts such as Rembrant, Constable, and George Bellows via David Park and into more “contemporary” artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Hockney, Kieffer or John Walker the Scotish painter who teaches at Boston University. I applaud him for proving that painting is certainly still a valid relavent and interesting medium,one no where near extinction thanks to artist such as he. Sam Altekruz

I got to see this show today. very impressive scale! I especially loved looking at his treatment of sky through smoke. thanks again for posting the interview.

Jade, I’m envious you got to see his show! I try to make an annual pilgramage to NYC a week or so before Christmas to see what I can – I’m bummed I missed his show. Thanks for your comment.

Right now I am working on a new article about Sangram Majumdar’s paintings and he agreed to answer a few questions about his work. Hopefully I will be posting it soon.