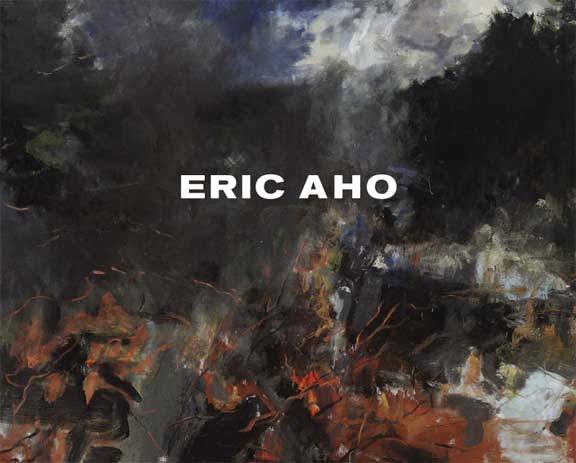

Eric Aho Catalog cover to current show at the DC Moore Gallery

I am pleased to offer this lengthy interview with Eric Aho, a major artist working with the contemporary landscape. Eric has a show that just opened at the DC Moore Gallery in NYC from October 8 to November 7, 2009. Eric received his BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art in 1988 (where I got to know him as a fellow student) He finished his postgraduate studies at the Institute of Art and Design in Lahti, Finland. He currently lives in Vermont with his family.

This past month he was elected National Academician of the National Academy. Eric has also received a Fulbright Scholarship in 1991 that allowed him to live and paint for years in his family’s native Finland. Additionally, he received a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant in 1994. Eric has show in museum exhibitions including the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Connecticut, the National Academy Museum in New York City, the Fitchburg Art Museum in Massachusetts, the Fleming Museum at the University of Vermont and the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College.

For many years Eric painted plein air landscape as well as larger studio works that drew inspiration, in part, from observational studies. His uniquely inventive and expressive style often shows affinities with a wide range of artists such as Gustave Courbet and the premier coup painting of Edwin Dickinson as well as the abstract expressionist painting of Willem de Kooning or minimalist paintings of Ellsworth Kelly. He has graciously given up his time and attention to this interview and I thank him profusely. There is a catalog with an essay by Bonnie Costello of his current show available from the DC Moore website.

Please note there are some slight edits to the written text of the interview from the podcast version, also please note that all the images can be viewed at a larger size if you click on them (which is different from what is usually seen here) You can download the podcast or listen to it from the bottom of this page.

Eric Aho Blasted Tree 2008 Oil on Linen 50 x 70 inches

Larry Groff:

Eric, can you say a few words about your background? I understand that years ago, your focus was more on printmaking. Can you say something about how your printmaking, specifically your monotypes, has influenced your painting?

Eric Aho:

That’s a good question. It’s really come to the forefront lately, in the past couple of years, as I’ve been, in a way, stepping out of direct plein air experience in the landscape [and] going into a more memory and experience-based approach to the landscape..

I’ve had to resort to things that have been sort of packed away in those mental bags, for a while, which was the printmaking, that I was essentially brought up on at my undergraduate — as you know, at the Massachusetts College of Art, I was a printmaking major. I worked on etchings there, and lithography: I mean, all the techniques; but I really found the monotype to be the most suitable, and suited for painterly purposes, although I hadn’t yet started painting, at that point.

But I put the printmaking down for about ten years, and pursued painting on canvas; oil paint, outdoors, for the most part.

Eric Aho Copper Field Suite XXIV 2006 Monotype 22 x 41 inches

LG:

Can I just ask you how you chose to go into painting outside?

Eric Aho:

It’s kind of a funny story. I was enrolled in the graduate program at the Massachusetts College of Art, and I left after one year, not finishing my degree. I took a teaching job at a small arts-oriented high school in Vermont, called The Putney School. I was going to be teaching painting, and I had never painted. [Laughing]

I had used black and white paint, and some umber paint, to essentially make wet, tonal drawings, but after working on a number of these — I remember George Nick in passing — he was never my teacher, specifically, but he would often come around.

I’d be working on these tonal, brown and white, wet canvases I thought they were paintings, you see. I thought they were really about painting. And he looked at them, scratched his chin and said, “So, when are you going to start painting?” And then he walked out of the room.

So three weeks of work just fell away, and I thought, What the heck have I been doing? And it really wasn’t until fairly recently, that I fully understood what he was talking about, in terms of the magic and the plasticity of oil paint, and what can be done with it; and, specifically then, with color. So that’s another matter, altogether.

But I had never really painted, and I took this job to teach painting, and said, Well, how hard can it be? So I showed up to this boarding school in rural Vermont in July, and my classes started in September, I had two months to start working.

By the end of those two months, I had some twenty or thirty little paintings, and I was kind of on a roll, just stumbling my way along. The questions I brought to my class on the first day were essentially the questions that were at hand to me, at that very moment: questions about temperature, and scale, and how do you connect to where you’re living, and how do you investigate with this particular medium? How do you answer those questions, and build a parallel world?

My students, actually, turned out to be far more experienced than I was, as a painter, but my head had already been in the world of making things for several years, since coming out of school.

It was an interesting experience, that was; and I feel like those habits that I developed there, I still use today: thinking and responding quickly and succinctly is sort of my approach, and I try not to second-guess myself.

And the print, the monotype, really helps underscore all of that. It’s a tremendously rapid-fire and immediate process, or it can be. Of course, the accident that one can almost always expect is part of the excitement of it, and it’s fun to carry over that into painting — the search for the unexpected, in a way; of finding ways of setting up accidents for yourself, so that technique doesn’t become overemphasized in the process of making the painting.

Late Squall, the Connecticut Oil on Linen 60 x 70 inches

LG:

So, you said, initially, your monotypes have particularly influenced your more recent body of work, where it’s perhaps more coming from memory and from other sources than direct observation.

Eric Aho:

That’s right. Specifically in the last two years, I’ve developed an exchange between my work in monotype and my work in my painting studio, where every couple of months or so, I’ll go into the print shop and kick around some ideas. Ideas can unfold much quicker in the monoprint process than they can in the painting studio.

It’s like a sketchbook, in a way, of getting ideas out of my head, and in a way finding out which ones are viable and which ones are just not worthy of pursuing right now; then I can come back into the studio, charged up by that experience.

So I’ve had pretty good luck at going back and forth like that, for the past couple of years. I should think about it a little bit more, but I think in many ways, the printmaking has really pushed my painting along quite considerably. I’ve been paying more attention to it lately

Soft Evening Sky, Ballyglass Oil on Linen 24 x 24 inches

LG:

What role does painting from observation play in your work? In your plein air work, what size is typical for you? What type of reference material, if any, do you use in your larger paintings? What difference, if any, do you see in your work when you paint directly from life versus painting from memory, studies or photos?

Eric Aho:

Well, I think now that I’m coming to terms with not painting from direct observation any longer, or at least, direct observation for the majority of my work — I’m still drawn to go outside.

But for twenty years, it had become my daily habit of packing my bag, loading up the van and going out to X, Y or Z spot, depending on the day or season or type of weather. That instinct is still in the bone right now, so when the clouds are breaking and the light is really crisp, it’s kind of hard to reconcile that loss, that change, that shift, and to then go into the studio. But there’s something about that tension that’s exciting.

Strangely enough, the work that I’m doing in the studio relies so heavily on very close observation, because I’m not looking at grand vistas, anymore, and more pastoral landscapes, like I had done in these views over the river. I’m actually looking down, more at my feet, into the river. – The Saxton’s River, which I’ve been watching freeze and thaw in successive winters now for the past few years.

There’s something about taking the recognizable details of the landscape; those being the trees and the hills and ridges, [and] just focusing on the immediate constructions of chaos and order of the shapes before me. I have to develop a particular accuracy around those blues and greens and yellows and strange occurrences of pink in the ice, and I have to be able to translate that in a very real way back in the studio.

My big studio projects usually start with one or two small studies from life, and then that will set me off for a couple of weeks in the studio. I’ll have enough information to work from.

Typically when I work outside, I’m working on canvases that range from 10 x 12 inches to 30 x 36 inches to, on occasion, something that’s 50 x 70 inches. The biggest paintings require a little bit more planning. The weather has to be suited. It can’t be windy. I’m not going sailing. I’m not interested in sailing.

Small Puritan Oil on Linen 30 x 36 inches

LG:

Did you see the Antonio López Garcia show at the MFA?

Eric Aho:

I did. I saw it several times.

LG:

They had a great photo of him and one of his big — it looked like 50 x 90 inch or bigger — paintings up on a hillside there, and he had it all tied down with cables and everything. It really impressed me.

Eric Aho:

I know. That’s impressive. That is a commitment beyond human, I think. It’s an exhilarating feeling to be out there with any size canvas; but essentially to be able to take the studio outside, which is the attitude that I’ve adopted, where, I don’t really have a studio setup. My painting bag and the few tubs that I have that have various paints in them, and my mediums, and things like that — I take that into the studio from the outside.

I bring the outside in, and I take the studio outside. I’ve tried to create this seamless experience, back and forth, so even the work that’s done outside has the feeling of something that could be accomplished in the studio, that it’s not so directly tied to this painting was done outdoors, in a response. There’s really no way to tell where it was done, or how it was done. It just occurs.

That’s been fun. That’s especially challenging when you’re working in the studio, then. How do you really make it feel like it’s a direct response to nature? I think it still can be, but I think memory can offer that direct response, and if you’re really paying attention to how things are observed and understood — at least that’s my goal.

LG:

Peter Campion, in an essay on your website said, “When Aho paints the world in front of him he doesn’t represent it so much as he confronts it.” How important is the specific view of the landscape you’re painting, or is the landscape more of a point of departure to explore formal painting concerns, or perhaps, inner landscapes, as well?

Eric Aho:

I’m not sure if one is more important than the other. These days, when I pick a spot in the woods, or I pick a sight at the river or in the quarry that I painted a couple of summers ago, I’m looking for some kind of totality of experience — where the pieces of the puzzle don’t align themselves so easily and where the sense of light and time is in some constant stasis.

Several years ago, I experimented with making paintings that were done over successive sessions, like from 1:30 in the afternoon until 3:00, and then I would stop the painting and come back to it the next day, and try to really focus on that specific time. But eventually that way of working kind of fell away, mostly because I just couldn’t ever get out at the same time again. There are too many variables, other life variables that came in.

But I realized that I could focus on a piece of the landscape and make a comprehensive experience from it. It could be the light from the morning on one side of the painting, and the light from the afternoon on the other side of the painting — but those two opposite times of day would just add up to the experience of an entire day in the painting, it would have a fullness to it.

I can’t remember the specific piece — I think it’s at the Hillstead Museum in Connecticut — but it’s a Monet painting of one of the haystacks, and it has shadows going in two different directions. So he was aware of that, too, and possibly just, in a way, having fun with messing around with nature. But on the other hand, the result is that it creates a dynamic fullness to a painting.

But that idea of the landscape, as this sort of jumping off point, or point of departure, I should say, I think it is really important. It seems to me so perfectly suited to the material of paint and the act of painting: that there’s a slow pace of change, that there’s a weight , and veils of thinness in the landscape that are direct parallels to the medium of paint itself.

And then there’s the weight of implied figuration. Such as the figure in the forest, of the viewer: the painter, the viewer, all present at the same time sharing this experience.

One of my goals recently has been to try to make the painting experience an essential equivalent of that natural experience. And to do that, I have to both look really really closely, and pay attention in a very formal, very particular way, in a response; and then I have to also rely on memory and invention, almost in equal parts.

That’s a little bit of the seesaw that I’m riding. It’s a lot of fun, and I don’t ever really know where the painting will end up.

Ice House No. 6 Oil on canvas 22 x 24 inches

Audio Podcast of interview (approx. 1 hour) – right click to save to hard drive

[podcast]http://eric-aho-interview.s3.amazonaws.com/ericaho.mp3[/podcast]

Interview with Eric Aho – Part Two

Interview with Eric Aho – Part Three

Both of these interviews were just terrific! Thank you Larry, what a great opportunity to understand the thinking of two truly gifted artists. Lots to ponder.

Thanks Randall,

I’m glad to have gotten the opportunity to put a little more into the world about these two great painters.

I didn’t know about Eric Aho until today. When I conducted a google search of this artist I was really pleased to find this as I’m also a big fan of Painting Perceptions.

Excellent interview. I look forward to reading the rest of it. These are the same questions or ways of painting that I have been dealing with for the past couple years or so. Good stuff!

Small Puritan, Ice House…. Wow!!!!

my wife had eric as a student and he did several pen an ink drawings for her while in high school which we still have you could see the talent was there he has become a very accomplished artist

In a recent interview in the Brooklyn Rail, artist Alex Katz said that you don’t need talent as much as ambition… and willfullness, to become a successful painter. In the case of Aho, he has been nothing but ambitious, but his talent is that of a quick study. His work is derivative of Stuart Shils, under whom he studied, and others such as Wolf Kahn, to name only two. Aho is quick to borrow someone else’s achievement to further his own career… everyone’s painting improves over time just through the daily practice of it, but to have that central, essential kernel of perception, genuineness and originality of vision takes a true master. That’s not what we have here. We have a careerist who focus is money and fame.

I disagree with Peter Roe, Aho has his own voice.

Whoa dude, that’s kinda snarky. Show me any painter who is not a “careerist” and I’ll show you a failure with a lot of paintings hanging in the homes of their relatives.

Peter, this is a rather angry note. Aho did not study under Shils or Kahn, but rather Henry Isaacs, George Nick and Norman Ackroyd. Aho happens to know the other two. Personally, I can’t see what it is you are getting at. If his focus is money and fame, I guess I’ve helped him get there.

I disagree with Peter Roe, Aho has his own voice.