I’m pleased to share a recent skype conversation and email interview with fabulous young painter Chelsea James to talk about her unique approach to painting landscapes, interiors and still life. James is currently a Utah based artist but with an eye on moving to France with her family in the near future. She shows with the Dolby-Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco.

From a 2010 Dolby-Chadwick Gallery press release:

“Chelsea James earned a BFA in Painting and Drawing from the University of Utah in 2006. During her undergraduate career, she was the recipient of numerous scholarships and awards and has since shown work at a several galleries and museums throughout Utah and California. Southwest Magazine, Salt Lake City Magazine and, most recently, Design Sponge, have praised her as a talented artist on the rise, one whose technical prowess and earnest imagination render her worthy of close attention…”

Ms. James has had a solo show at the Dolby-Chadwick Gallery in 2010 and a two person show in 2012 Bakersfield Museum of Art, Bakersfield, CA. She was also part of a 2014 “Salle De Notre” Salon show at The Louvre as well as numerous other venues which you can see from her website.

Larry Groff: What made you decide to become a painter?

Chelsea James: I was naturally drawn towards drawing and painting from a young age. It was intuitive, I felt like painting and drawing was made for me, it was a language that clicked. I chose painting because I needed to be true to myself, and I knew that it was the only path for me.

LG: Was art school a positive experience for you?

CJ: I really submerged myself into school and took full advantage of my time there. I feel really lucky for my time at school because I was taught the fundamentals by a group of really amazing professors–David Dornan, Paul Davis and Tony Smith–Who stressed the importance of color, value, and drawing. The fundamental first year of school was notorious for being tough on students, I remember a lot of tears and students leaving the program. But for me, I took the criticism as a motivation, and it propelled me to work harder. It taught me to have thick skin.

After my freshman year, I studying under Kim Martinez. Her approach was to expose me to as many types of painting possible and to really try and get me to think outside the box and experiment with my painting process. I feel lucky to have had the contrast of education–the fundamentals, and the conceptual.

I started going to some art workshops in Helper, Utah after my sophomore year and that became the highlight of my school experience. I was surrounded with other artists talking, breathing and thinking art.

LG: You became successful very early in your career, showing in a gallery while still in school and were invited to join the prestigious Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco soon after you graduated. How has this early success affected you?

CJ: The attention I received from my first gallery in college felt really good. With a gallery–shows and deadlines, I had to learn quickly how to frame, paint on a schedule, and make it work. I learned habits that really help me today. The early success gallery put me a little in a trap though. It felt good to be recognized and to be pleasing people, and I ran with that, trying to paint what I thought would sell or the gallery would want. When I stepped off that platform, and started to paint what I wanted, that’s when Dolby Chadwick contacted me. I needed that kind of motivation to keep painting. It’s easy to come up with excuses in life, and when you have kids, your time changes. It was the push I needed. Dolby Chadwick gave me the confidence to paint what I want, to listen to myself and to paint no matter what. And because I can make an income, I’m lucky I can afford to hire help with my family so I can still paint.

LG: What landscape painters and paintings have been the most meaningful to you?

CJ: Vincent van Gogh really comes in mind when I think of influential landscape paintings–but I am more drawn to his landscape drawings and how he describes the forms. Antonio Lopez Garcia is the kind of painter that makes you want to paint when you see his work. He makes it feel effortless, alive, atmospheric. It touched me and created that interest to try something similar.

John Dubrow’s Jerusalem landscapes really spoke to me. They are perceptual, but have an abstract element about them that I really like. Alex Kanvesky’s landscapes are also an influence in my work.

LG: You studied landscape painting with the Utah artist Paul Davis. What was that like?

CJ: What I like about Paul is his ability to teach in a simple way. He breaks down the process into simple, basic steps and that really worked with my brain, it’s very formulaic, almost mathematical. He would do underpainting and just focus on that, after the underpainting focus on matching all your colors–make sure you get every color right. Then lay the color down and paint darks first, thin to thick. As a student, I needed that kind of direction, steps on how to do it. It seemed that trying to paint by myself and not have any base just seemed too overwhelming. This formula, if you followed the rules–it worked. The work would just appear, after doing it you’d say wow, that just happened I can’t believe I just did that. I did this for a while, but it can get you into a trap too.

The way he taught drawing really clicked with me too. It’s also a very systematic approach. Do you know triangulation? We would work with triangulation, measuring, and blind contour. I had teachers before that say just fill the drawing or just draw what you see and to me that was too vague. I needed more of a structure and the way he taught gave me freedom in the long run.

Some people might say just paint how you feel and want to paint and think that teaching approach to be too restrictive. I didn’t want to do that without the tools, if you have the foundation, those tools, then you understand color, value, drawing it gives you so much more freedom to paint or draw however you want. Knowing these foundations gives you the confidence to lose your drawing; if you’re drawing is good but the painting isn’t working you just wipe it out and draw again. But without that confidence, without that knowledge, the painting becomes precious and you get scared to explore. That’s more or less what he taught.

LG: You mentioned about triangulation in drawing, can you explain a little more about that?

CJ: It’s not a grid, working on a grid doesn’t work for me, that’s too confining. Triangulation may sound mathematical or scary but all you are doing is finding points and angles in the body. For instance, you find the tip of the nose and relate it to a shoulder and to the earlobe and once you find the relation to that, everything builds on this. So if you want to find where the arms start and you’re doing the head then I would draw the angle and then figure out where it hits on the body. If you draw enough and you train your eye to do what the pencils doing then you don’t ever have to measure. I don’t ever measure anymore with my hand because I trust what my eye is doing.

LG: So you’re relying less on measuring proportion and more on the relationships?

CJ: You’re doing proportion and relationships at the same time. Measuring with your eyes, not your hands.

LG: How much does this way of measuring does this offer you an intuitive feeling for proportion that you can use when you’re working from invention?

CJ: It does become more intuitive, when you’re first learning you really have to think about it. Learning triangulation properly took me about a year to truly feel I understood it. After that I didn’t even think about it. I do this all now without even thinking, it moves really quick.

LG: How important is observation to your current work? Are your interiors and still life from observation? Do you also paint outdoors as well as your studio landscape inventions? In what ways do these activities influence each other?

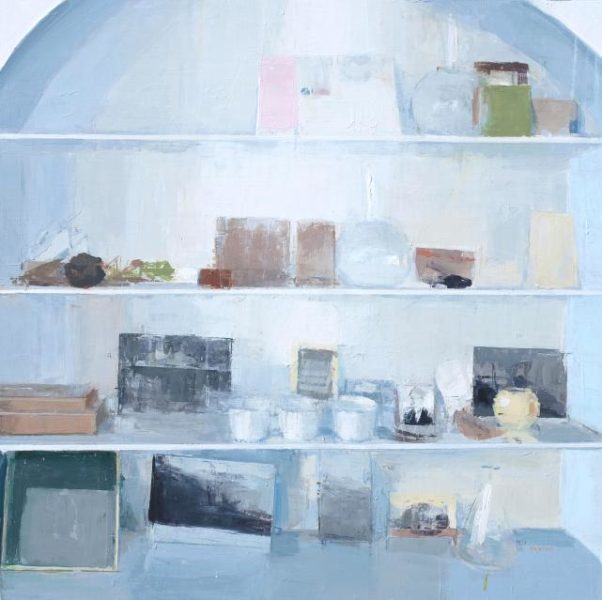

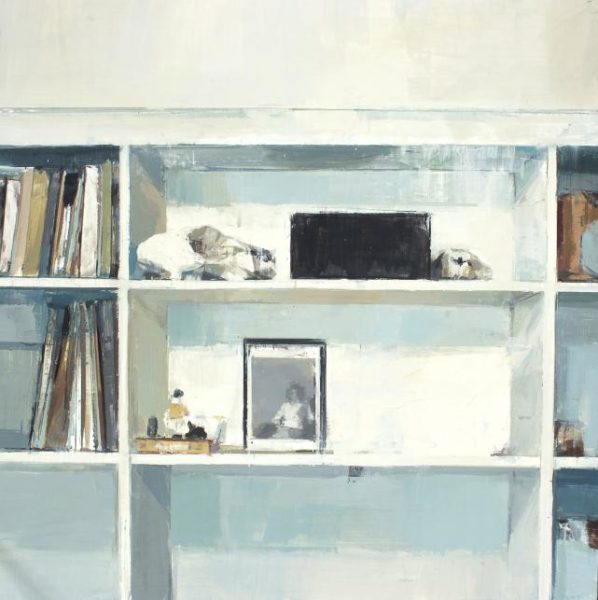

CJ: Observation is important in my still lifes and interiors. It fulfills my desire to draw, and I get so much pleasure out of painting something and to see it come to life. I like the disciplined nature of drawing, there is something about the process that makes me get lost in time. I can really escape my life and it’s almost meditative.

They feed me in different ways which is why I do this, I’m doing this for me and they’re both completely different. With the landscapes, it’s more of an emotional, expressive activity. I want those paintings to feel emotional, I want them to evoke emotions in people, to think outside the box and wonder where is this? What is this? That’s where I’m going now with my new landscapes. Sometimes when I’m going through something hard in my life I tend to be drawn more to the landscapes, it helps me work through these feelings.

There’s a part of me that really enjoys drawing representationally. I get great pleasure from this. The interiors and still lifes allow an opportunity for a story to happen and that really interests me. When I’m curious about something I tend to go in that direction. I don’t always work from life with my still lifes, I’ll work from photos and sketches but also I’ll sometimes do them from life.

When I’m working from life I feel like I have less freedom, I can feel a little locked in. When I work from photos I’m more willing to experiment with things like color and edges. I am thinking about exploring interiors from observation with my process and see what that looks like.

LG: Why do you feel that observation is less freeing for you?

CJ: Working from observation is often the best way to go for artists and if I were to give advice for anyone I would say paint from observation. However, personally I got rather stuck in a rut with that approach. I had a formula with working from life and that’s all I did. I painted still lifes in this way but after awhile I got really bored with that process. Because it was sitting in front of me I felt compelled to paint it exactly how I saw it.

LG: But isn’t that just what you’re bringing to it? Not the process of working from observation itself? What’s to stop you from painting it differently from what you see? I would think it’s more your personality, your history–what you’ve been taught in the past that is more the issue than the observational process. Don’t you think there is also a risk of being formulaic in imagination based works?

CJ: I think it’s in my head for sure. I agree with what you say here and working from observation is the best but I first need to merge these two worlds. My tendency is to go back to my previous approach to observational painting because it’s safe and I want to do something different now. Perhaps now I could do this again and it would be a lot different. I have a very different perception of painting now. Before I was in this “want to please” mindset.

LG: It’s certainly good to shake things up every now and then – especially when you’re younger and finding your way to a certain degree. I’m very impressed that you rebelled against your own success with precisionist realist painting to a much looser, abstract direction. In a short time you’ve made an incredible body of work. My hat’s off to you to get this success so early on in your career.

CJ: Absolutely. Thank you.

LG: Do you ever work with the figure?

CJ: I haven’t yet but I want to for the future. The figure in the landscape interests me a great deal, probably what I love the most. However, I don’t feel completely ready–I want to feel comfortable with this first, for the figure to come naturally. I do draw the figure a lot.

LG: Do you have a routine with your drawing?

CJ: I try to draw before I paint almost every time I go to my studio. It loosens me up and I love drawing. There’s vulnerability in drawings that I try to capture in my paintings. I tend to like drawings from artist more than their paintings. They feel more raw and vulnerable.

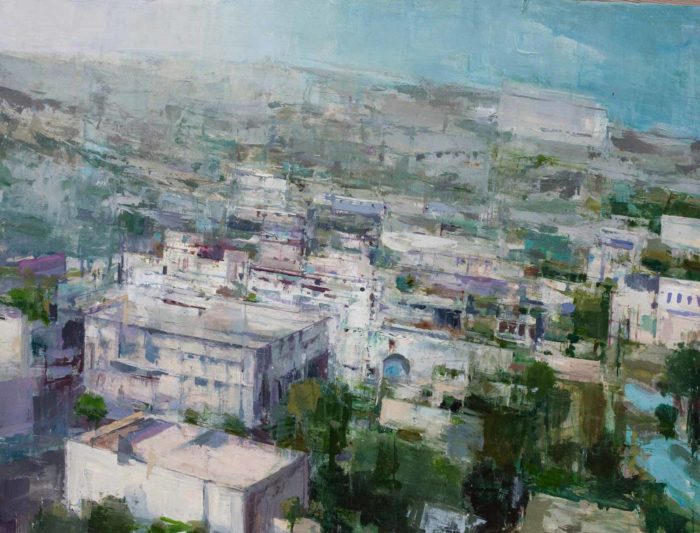

North 24″ x 36″ oil on masonite

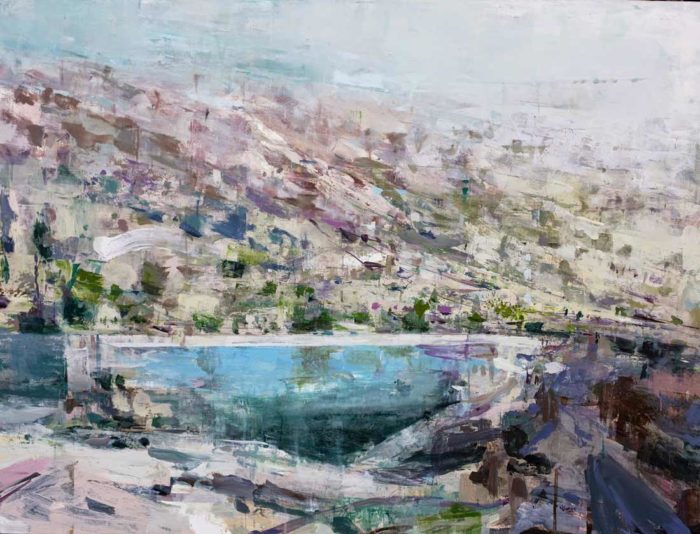

Crossing, 48″ x 60″ oil on masonite

LG: Back to your landscapes, is it important to you that your landscapes have a naturalist believability?

CJ: This had been true previously to a certain degree but not in my new work, especially with the figure. I want people to question is this a landscape? What are those objects in here? I’m trying to merge the two worlds. It’s not important to me that people think it’s believable. I’m just painting how I like to paint it.

LG: So if you felt an area of the painting, the sky for instance, wasn’t as important to have a naturalist coloration or be convincing in terms of spatial recession and more about the energy or feeling of the paint?

CJ: I think it’s both. I am using a lot of the knowledge I have from landscape painting. If I want it to recede then I might lighten or cool a color. Or I might de-emphasize details in the background to push the space back more, to simplify as much as possible. But if I’m going to make certain marks I’m going to make them in the foreground because in the back they would push forward and that’s not what I want. So I’m thinking about those things when I’m painting because that knowledge gives me a lot of freedom to use whatever value and color I want for creating my own landscape.

LG: So it’s still important to you to maintain the idea of a window onto the world as opposed to strictly being about the flatness, the objectness of the picture?

CJ: I want it to be believable and make sense. But I also don’t think or plan it all out, it is more of an intuitive process for me. But it still has to make sense, when some people draw the figure and they intentionally distort the figure, I think that can be really interesting but it still has to make sense, have it’s own internal logic. I’m trying to do the same thing with the landscape.

LG: Some of your landscapes have a high vantage point or distant view as seen from an airplane or mountaintop. What are some of your thoughts about this?

CJ: That is just something that I found interesting and was curious to explore at the time. I was traveling a lot then. My husband’s father is a retired pilot and we traveled a lot. I was looking out the window of airplanes and captivated by the space and atmosphere and how everything was subdued.

LG: Where were you flying? I imagine they come about from aa fusion of invention and memory but do you think of them as being of a particular place?

CJ: They’re not about a specific place but some of them are from Europe, a few from Africa. I would combine drawings and maybe make up a little of my own landscape.

LG: I understand you spent time living in India?

CJ: I lived in Jaipur in Northern India–my twins were born there.

LG: You work with several paintings at the same time. Please tell me a little more about that.

CJ: When I stopped painting still lifes I wanted to start a new process. I wanted to step back and think about how I was going to make these paintings that might take a year or two, to figure out a way of painting that was fun as well as being efficient, especially since I am making large paintings. By working on several paintings all at the same time I could work on one layer over maybe four paintings–starting on one painting and by the time I got to the forth I could then go back to the first painting and it would be ready start work on a second layer. As I’m working on my series I’ll learn things from, say the sixth painting, that I can then go back and incorporate into my first painting. So they evolve together. I find that if I do a series and just paint one painting at a time by the time I get to the twelfth painting it feels so far ahead of the first painting that they would exist in two separate series, that they don’t feel cohesive.

LG: So you wouldn’t want to go back to the first and bring it up to the same level as the last?

CJ: I do want to have them all at the same level. If one painting feels left behind, I will work on that painting until it’s at the same level. I then I’ll feel like they’re having a similar language. They just work better and I learn more in the process. This has been my favorite way to work. If I now work on just one painting from beginning to finish I can get stuck in my own painting, I’m not stepping back enough, I’m not giving myself enough time to think about how I’m going to resolve the issues in the painting. Sometimes I work on a painting for twenty minutes and then set it aside for three weeks. When I set this painting back up it’s like I’ve resolved those things already and it just seems to progress further.

LG: Would you say that by not working on just one painting you’re less apt to make the painting so precious, that you are less emotionally entangled in ways that might diminish your ability to see the work objectively?

CJ: Exactly, if I’m working on say ten paintings and three paintings aren’t working it’s easy to see this and to start over or even toss those paintings out if need be. This process gives me a sense of freedom, where I’m more willing to take risks or make mistakes. If the painting becomes precious I know from the next painting that I can knock it down and bring it back up.

LG: So what about your subject matter from one painting to the next? Is it markedly different or do they all have a similar theme?

CJ: It’s important that a series be cohesive, in a similar grouping, even if send them to different galleries. Right now I’m working on a small series of desert landscapes where I’m incorporating the figure. It’s not just completing one painting, I’m trying to work through a problem. I have this idea where I want to try something different and it seems to progress better for me that way. For instance I might have an idea about doing a group of interiors that are about things people left on a table, maybe five different paintings. I’ll just set them up around my studio and do one at a time and see how that works. They may then evolve into something else and then I’ll go from there.

LG: Your painterly touch and inventive mark-making gives an openness and atmosphere that is very compelling. Can you tell us something about how you go about making your paintings with that in mind?

CJ: I like to look at paintings up close and far away, I get a lot of pleasure out of the mark making. When I’m painting I’m not thinking about my process of using a dowel to make crazy marks – I’m thinking about how best to solve a problem with space in the painting. I might be painting some bushes and think how can I make this without using a brush and still have it looking like bushes. I’ll try it with a dowel and maybe a roller or two or later use another tool, I’m subtracting and adding at the same time, I’ll also glaze and form relationships with the tools. It’s all fair game. I’ll use my paper towels in a roll to paint with, use the whole roll at once. Whatever’s in my studio is up for grabs. Making marks in this way create mistakes, moments needing adjustments, fixes and mistakes layer on top of each other and over time becomes incredibly exciting. It’s really fun. This is perhaps the most enjoyable part of painting for me. That’s often what it comes down to for me, I love being in my studio and love every step of the process.

LG: Are you familiar with the still life painter Walter Murch? He taught at Boston University for many years. The story I heard about him was that he would often leave his paintings, works in progress, on the floor so that they would be stepped on by himself, students, whoever. The random nature of the footprints and such would disturb the paint surface in ways that helped him look at the painting and go back into the paintings with new directions for edges, marks, tones and such. They are incredible paintings in this regard, that freedom of experimentation.

CJ: What you say about him walking on his canvas, that’s really cool. You break up the process and your routine to make unexpected marks and then you have to react to that. Doing this for me has stretched me as an artist, took me out of my box.

LG: Do you use a traditional palette? How do you go about setting up your palette?

CJ: I’ve made a different process for myself and I’m thinking of switching it up. If I get too comfortable I get bored and then I totally switch up my process. Right now I work with an acrylic underpainting. I’ll mix colors that I’m drawn to and then mix three different values of each color and a warm and a cool. I’ll use those colors for my underpainting. It takes up the color matching, one less thing to think about. I work from there on a wet on wet process. This dries faster and allows me to work faster and add more layers. The acrylic is really flat which I like in the beginning stages, I like the way it abstract things. I will then put the acrylic paints away and then set up my oil palette in a traditional way and then mix large chunks of color and go from there.

LG: Using acrylic for an underpainting seems like a very smart way to work especially if you keep the paint layer thin. Also it would cut down on the toxicity of using solvents with oil paints, be less volatile, especially important if you have kids around I should think.

CJ: I had a professor, Tony Smith, who had us go out into the landscape and draw the landscape, block in our simplified areas with acrylic and then bring it back to the studio to glaze on top of it with different colors in those sections. The next day you would then work on top of that with oils. This led me to my current way of working.

My landscapes are more open ended, I feel like there is nothing more I can do they just feel done. Sometimes I might set them aside and I’ll come back a month later and think that it looks unfinished and then work it into it more. But it’s a delicate balance for me not to overwork them, for the paintings to stay open. If I overwork them one time I’ll say I have to stop before they’re overworked. I have to figure out that balance.

LG: How can you tell if it’s overworked or not? What does that mean to you?

CJ: It feels labored and the freshness is gone. The energy, the intuition feels stale. You have to catch it at a moment of being through a struggle; I don’t want them to feel too easy but at the same time not too labored. If I feel like the painting is starting to feel overworked I won’t start over but I’ll put more marks on the painting and really break it up and try again. This will often bring back freshness to some degree.

LG: Some might disagree with you here and say it’s not really a question of a painting being overworked it’s more that they haven’t gone far enough, they haven’t resolved the problems or just that the painting isn’t finished. For some painters maybe what needs to happen is for them to scrape it all down or to sand the painting and start fresh. I say this because I sometimes think the notion of a painting being overworked is sometimes overstated, even though it sounds right at times. However, I understand what you’re saying and of course the danger of being overworked would apply more to your loose style of painting more than someone going after a tight, precise realist style. However, sometimes I worry that some painter’s fear of a painting being overworked can lead them to stopping a painting too soon.

CJ: Sometimes with my still lifes I do need to keep working and pushing further when something isn’t working out. You can see where I’m struggling here and sometimes I do like that sense of struggle. I remember painting a paint can that was difficult and I worked so many hours on that one paint can and I finally had to step back and put a big mark in the middle of it and break it up to free myself of it, to give the painting a fresh start again.

iframe width=”640″ height=”480″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/VxdrIiMPRYk” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen>

Link to the Savvy Painter podcast interview with Chelsea James.

It looks good. Definitely a contemporary style. But I do feel like it is quite derivative. I think she is trying to make a type of Kanevsky style in her work and while it looks good, it seems to me as though I’ve already seen this before even though this is my first time coming upon her work. Maybe as she matures, her own style will emerge out of imitation.

These are beautiful, original paintings; I wish I could see them in person. Clearly Ms. James is a natural born painter. Her work sits at the grown-up table where it contributes to the big dialog.

The ‘anxiety of influence,’ and the ‘comedy of similarities,’ aside, I find James’ paintings inspiring for their courage. The courage to embrace what you want to do is no small task. Even being self-aware enough to see the difference between what you want and what you think you should want is olympian. James’ steely eyed gaze was always cutting through, and I think the visual ideas hinted at in these paintings foretell…

I can’t help but agree with Ivan. I think Chelsea is very talented but if you look carefully at Kavensky’s work, and especially his colors, there is a striking similarity. I’ve been following her work for years.

She produces wonderful work. I have never heard of Kanevsky and so I looked him up. You’re right. There is a strong similarity. Is it even possible to do original work anymore? Everyone is derivative unless you’re an outside(r) artist.