I was delighted that Caren Canier agreed to an interview with me at her home in Gubbio in Umbria, Italy this past summer. We talked in her studio for over an hour about her process and background in how she makes her fabulously inventive collages. We also discussed how her paintings from observation relate to her collage work as well as some interesting issues surrounding figurative art making.

Caren Canier studied with Philip Guston and recently wrote an essay about her study with Guston, Memories of Philip Guston, that she shared with Painting Perceptions.

She also received a Rome Prize Fellowship and spent a year at the American Academy in Rome. Since then she has divided her time between Umbria and upstate New York, where she is a Professor of Art at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy. Canier has exhibited frequently in New York, New England and Italy. Recent comprehensive shows include a solo exhibition at the Painting Center in New York City and a two-person exhibition at the Exposition Hall of the City of Gubbio in Italy. She is the recipient of a New York State CAPS grant, two Artists’ Fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, and grants from the Ingram Merrill Foundation and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

Larry Groff: What were your early years like, how did you get your start? What was it like to study at Cornell for your undergraduate degree?

Caren Canier: I loved Cornell. Having grown up in New York City – I attended the High School of Music and Art – living in Ithaca was the first time I formed a strong attachment to the landscape and the physical beauty of the natural world. Cornell was, for me, an incredibly rich environment of gorges, vast expanses of sky and dramatic weather but also, wonderful libraries and facilities. Cornell is where I studied with Gillian Pederson-Krag and she was my most influential painting teacher. I first met Gillian in Freshman Drawing class when I was 17, and later took painting classes with her during my junior and senior years. I also lived with her for a few months after I graduated.

LG: And you’re still in touch with her today?

CC: Oh yes, we are very close friends. In fact, she was just here for 10 days, staying with us in Umbria. I love her work and think she’s a superb painter. Her work is inspired and by extension, she’s also an inspiring teacher. She’s terrific.

LG: Was there anything in particular you learned from her that stood out and helped you grow to the kind of painter you are now?

CC: What I remember most about Gillian’s teaching is that she didn’t teach a lot of technical nuts and bolts about painting or drawing but rather talked about design and the expressive power of color. She was most intensely involved in subject matter. We worked exclusively from life in her classes but she used to say that the most important question you have to ask yourself when you set out to paint is: what shall I paint? She encouraged us to find a group of ideas, visual ideas but also personal subject matter that we really loved and then to find the formal means through design and color to express those ideas potently. This is not to say that the subject matter was necessarily representational–Gillian is an enthusiast of abstract painting as well.

For Gillian, painting is a spiritual exercise. She’s deeply engaged in a spiritual life that has everything to do with painting. It has to do with painting as an expression of love, and the way in which painting has the capacity to reveal the spiritual – a sense of the unseen or the transcendent might be another way to say it. I remember that she used to say – since she paints landscape, still life, and figures – that she knew that she was getting somewhere with a painting, if the painting started to look like something other than what it was. So if she was working on a still life and it started to feel like a landscape painting, she knew that there was something bubbling up that was transcendent about the painting. Morandi’s ambiguous still lifes and landscapes come to mind.

I was 18 when she said that to me, but I still think about it today. I believe it’s true because great painting transcends the literal to create metaphors that affect us deeply. Gillian encouraged us all to create a visual language for ourselves based on our inner most loves and passions.

I believe that a good teacher or school teaches techniques and precedents from the history of art but also helps you to develop your own language to be able to express the ideas you have.

LG: You learn the master language but then go off to speak in the dialect that best suits your region of interest. We use similar words and it all gets understood somehow.

CC: Yes, I think that’s a good way of putting it.

LG: So then you went to Boston University for graduate school?

CC: Yes, I went to BU for my MFA and studied with James Weeks and Philip Guston, who were very different from each other. Weeks was a wonderful teacher. I remember things he said about the mechanics of painting and how to use the visual language of painting to create an engaging image. He was a good critic and also a very kind and gentle man, really supportive. He used to talk about dark-light design and moving through the space of the painting. Guston was much more focused on expression but he, too, was interested in formal ideas about painting. I think his work is very formal. He talked about Piero della Francesca frequently and the tension and plasticity of the forms in his paintings. I wrote about this in my essay about Guston. I think that the formal concerns that engaged Guston are lacking in many of the paintings people are doing now that are supposedly influenced by his work. Guston was terrific but most of all, the two of them, Guston and Weeks together, balanced each other very well. I should mention that I also studied with Gabriel Laderman when I was an undergraduate at the Tanglewood Institute summer program. Langdon Quin and I were at Tanglewood together in 1973.

LG: Is that when you met?

CC: We did but we didn’t really get to know each other until 1980. We were acquaintances at Tanglewood and attended the program along with a small group of other students. It was an intense, immersive summer program, something like boot camp for painters. Gabriel was a great teacher, very opinionated and very smart. He had fixed ideas about painting and made certain intellectual constructions that didn’t always make sense to me, but I respected him a great deal.

CC: I used to say that Gabriel Laderman had a big rolodex in his head with all kinds of information in it that he would access to talk about our work. I remember that he came to my studio one time after I had finished grad school, looked at my work and said: I know you are looking at Puvis de Chavannes. I was most certainly not looking at Puvis de Chavannes. Of course, I then went to look at Puvis because I respected Gabriel and was hungry to learn by looking at precedents. I’m still not quite sure what my work has to do with Puvis de Chavannes, although there are qualities in his work that I admire. Gabriel’s rolodex was always was working overtime, making connections between paintings and artists and figuring out what you were looking at and what else was influencing in your work.

I remember that one time, years later, Langdon and I ran into him at MoMA looking at the Balthus “The Street” and he said “look at that, the horses head!” I had no idea what he was talking about as there is no horse in the painting but then finally realized that he had a whole construction worked out in his mind about a shape, that was partly a negative space in-between some architectural forms that looked like a horse’s head. According to Gabriel, this horse’s head was somehow the linchpin of the composition. The idea was so obtuse that I could barely figure out what he was saying. But that’s the way his mind worked and he was good critic and a generous and caring teacher. I will never forget the time he worked on one of my figure paintings at Tanglewood, a terrifying but wonderful experience as I learned so much from watching him paint. He was putting big chunks of paint everywhere, all over, all at once. It had never occurred to me that you could do that and it was great.

LG: After graduate school you painted perceptual still life and then you switched to figure paintings…

CC: I had a crisis in graduate school because I was trying to make figure compositions from my imagination and I got really confused. I couldn’t synthesize the things I was observing to create the narratives that interested me and so, by the end of graduate school I was actually working non-representationally. I had a terrible crit with Philip Guston at the beginning of my second year and I didn’t show him my work for several months because I was so confused and upset. I didn’t know what I was doing, I didn’t know what I wanted to do and so I didn’t let him into my studio for a few months. He was very nice about it, saying okay, when you’re ready I’ll look. I got rid of all the subject matter, all of the habits from Cornell and started from scratch. I put paper up on the walls all around my studio, and eventually, big flat shapes of color started to emerge. I used this process to figure out what was fundamental and essential about my form and color sense.

The work evolved into long, horizontal paintings of large flat shapes of color that were kind of architectural. They had no figures or anything representational in them but you moved across and through them in a way that interested me and seemed essential to my experience of the visual world.

LG: Did Guston like this work?

CC: Yeah he did. He responded positively and said something like “I am glad to see you made this change–I think you are pointed in a good direction.” I was thrilled because at the MFA thesis show at the end of the year, my work was hung front and center,. This was something of a shock because BU was still pretty traditional back then. Guston and Weeks weren’t, but the undergraduate program in general was rather academic.

LG: What sort of things did Guston talk about? Was Piero someone he referenced a lot when he talked to you?

CC: Guston talked about Piero but in a totally different way than teachers like Joseph Ablow, who taught the graduate seminar at BU. Guston talked about paintings from the past in a much more direct and visual way. He was intellectual but also a little bit of a cowboy. He spoke directly and with an infectious enthusiasm that made you want to not just look at and think about the paintings but also feel them. It was about feeling the spaces, cadences, and the tension in the paintings. The more intellectual approach of Joseph Ablow was drier for me and at times his historical references went over my head. Even though I went to an Ivy League school I don’t feel like I was very well educated in any classical sense.

LG: Anyway, so it’s interesting that so many years later we look back on this time as if it was a few months ago.

CC: I know. Perhaps grad school was so important for me because it was like a battlefield. It was a very tumultuous time in my life. I was often miserable back then but in retrospect, I think it was a very good learning experience. My memories of that time revolve around Guston, Weeks and my friends. I was experiencing a lot of personal problems as well, so it was an intense time. As for my work, I was working like crazy, painting so much, working part time and very stressed out. My roommate from that period, painter and sculptor Susan Mastrangelo, has remained one of my closest friends and I still see a lot of her to this day.

When I got out of grad school I needed to get away from Boston and moved back to New York, which is where I’m from. I worked as a “Gal Friday” for the advertising department at Grumbacher and later as a gallery assistant at the Robert Schoelkopf Gallery. I knew as soon as I got settled in a new studio that I wanted to paint figures again. I stretched up some really big canvases and started painting the subjects that I had wanted to paint in the first place at BU. This time, however, I started having a good time in the studio and gave myself a lot more freedom.

I don’t know if they are really good paintings but they helped me win the Rome prize. I was less than a year out of grad school when I won the Rome prize and in 1977-78 spent a year at the American Academy in Rome. That experience totally changed my life.

LG: This experience in Rome seems to still have a big influence on your work. Why do you think that is; why it had such a profound influence on you?

CC: Well, first of all, I was hungry to look at Italian art. I was interested in Piero and other Renaissance painters and I wanted to look at Ancient Roman and Greek art in person. It was an incredible shot in the arm to win such a prestigious prize with a whole year to paint. I didn’t have to work, and found myself in one of the most beautiful places in the world. I had a huge studio with a spectacular view of Rome and I spent a lot of time just walking around the city, looking at things. The American Academy in Rome is partly an arts institution, but it’s also a program for classical scholars, historians, and archaeologists. The School of Classical Studies runs a lot of walking tours around the city, and they also sponsored trips to archeological sites such as Pompeii, Cumae and the Etruscan tombs outside of Rome. My education in the Classics had been so inadequate and I didn’t know anything about history; I just had been painting non stop all through undergraduate and grad school and taking some art history courses, but I didn’t have a sequence in my head of what happened when or how the artifacts I admired related to history. I went on all the trips that I could with the historians at the Academy and spent a lot of time walking around Rome, visiting the Forum and having these amazing scholars bring ancient history to life.

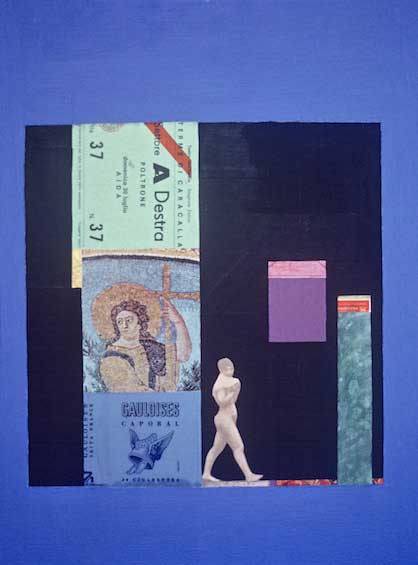

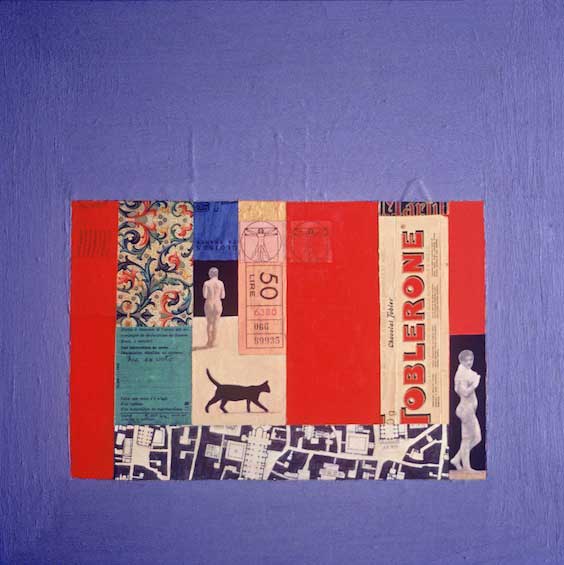

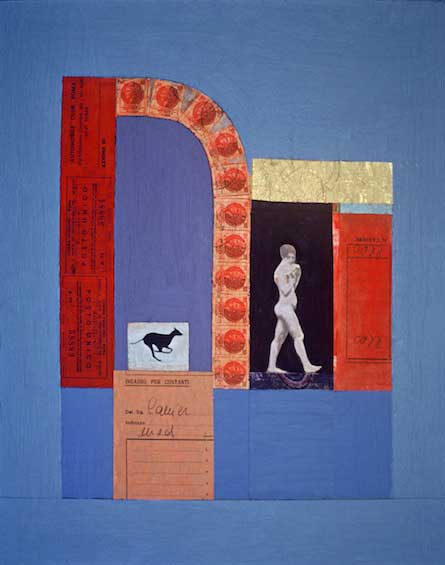

Woman Among Ruins, 1979, 14.75×11″, mixed media

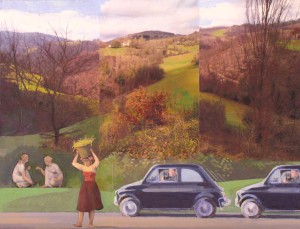

Albergo della Lunetta, 2005, 40×48″, mixed media/oil on panel

Something about the city entered my system, which happens to a lot of people who spend time not just in Rome but also in Italy. There is something about being aware of the different layers of history and how they exist simultaneously in this city that is so moving to me. I don’t know how else to describe it.

I bought a used car; it was an old Citroën Dyane convertible with just two cylinders that barely ran. I used to love to drive into the center of Rome and pull up next to the Pantheon in my little car. It sounds so silly, but there was something so moving to me about the fact that in 1977 I was sitting in my little car next to the Pantheon for in those days, you could still drive right into the Piazza del Pantheon. The contrast was shocking. There was something about this experience that was very collage like. In a sense I think that my collages were a way of absorbing all of the new experiences of being in Rome.

The other thing that happened was that I became close friends with one of the architecture fellows at the Academy, Judy DiMaio. She was very knowledgeable about the history of Italian architecture and painting and I did a lot of touring with her; she was especially passionate about Mannerist painting, and we took walking tours in Rome and traveled in Umbria, Tuscany and the Veneto together. Judy introduced me to her friend and mentor, architectural historian Colin Rowe, who was working on his book, “Collage City” at the time. With Judy and other architects at the Academy, I learned a great deal about architecture, and when I returned to the states I was hired by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to teach in the architecture program, even though I had no formal training in architecture. Because of my experiences in Rome, I was able to join the architecture faculty to teach drawing in the First Year Design studio. I had a joint appointment in Architecture and Arts for about 20 years, before moving to my current, full time position in the Arts Department at RPI.

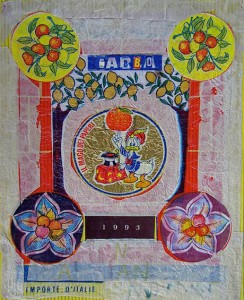

Meanwhile, I was collecting stuff; postcards and all kinds of printed matter such as train and museum tickets, candy wrappers and other papers. I have boxes of postcards that I collected that year, and I also had a lot of collage materials I brought with me from the States. I was making still lives in front of my studio window from life,

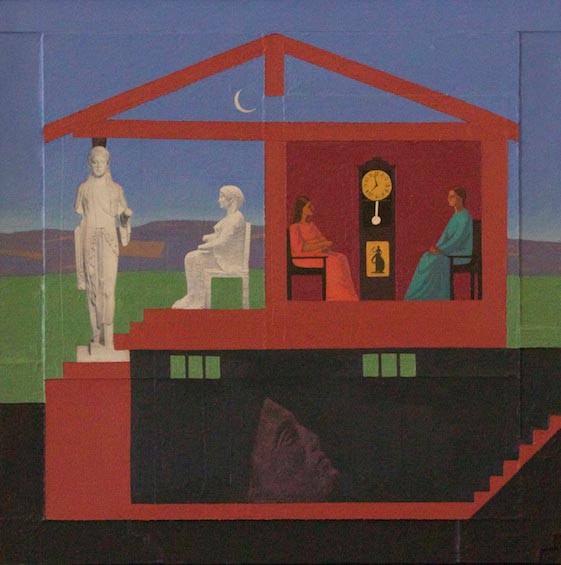

large, figure compositions from my imagination and also small collages. Later, I can show you the painting that I did when I was at the academy;

Three Friends, 1978, 71×81″, oil on canvas

it is a big, mostly pink painting of an aerial view of a room with people sitting around talking to each other, which was an idea that I had brought with me from New York. Living in Rome inspired these collages,

Roman Cityscape, 1978, 15×15″, mixed media

Woman Among Ruins, 1979, 14.5×11.5″, mixed media

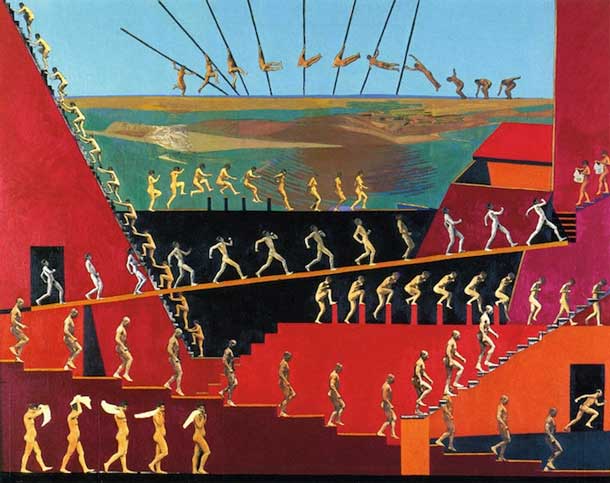

some of which were started in Rome that year and then finished later at different times. I had also brought along some Xerox copies of Muybridge prints of figures in motion that I had printed up at the Robert Schoelkopf Gallery when I worked there as a gallery assistant. I started cutting and pasting and making collages and I don’t know, that process just became part of my life.

I kept coming back to Rome; The second summer after returning to the States I did and I’ve come back every year ever since. Langdon and I met again in Rome in the summer of 1980; we bought our house in Italy in ’82. So I just keep coming back and gradually it’s grown to be a part of me. My friend Gillian Pederson-Krag says that our group of American, Italophile painters were all here together in a previous life. All of these people, many of whom are good friends–it’s a long list that painter, Mark Greenwold once referred to as the “figurative mafia”–keep meeting in Rome, crossing paths in Italy. Sometimes I look around and think ‘What am I doing here? I’m not Italian and this is so far from home,’ but by now it’s gradually become my home.

LG: How do you manage going back and forth from New York to Italy with all your collage materials?

CC: Some of the collage materials travel with me in a suitcase and others are collected in Italy. In both studios, I have boxes full of found printed matter dating from the last 40 years. Most recently, I’ve been making digital prints of my own photos and images that I find on the internet to develop into paintings. Recently, I’ve been starting paintings in the States, sometimes, large paintings that I photograph in progress, and then transport to Italy in the form of digital prints. One of the perks of teaching in an arts department that values technology is that I have access to a really good printer at school and technical assistance. I bring over high quality digital prints of my work in progress to create studies that I work on here in Italy in oil pastel or matte acrylics.

That way, when I go back to the States at the end of the summer, I’ve been thinking about the paintings back at home and have some evidence of my thoughts about them. I work very spontaneously on the prints to make studies and then I go back to the original. Actually, I’ve followed this process on the last few large paintings I’ve made in the States. I found a kind of oil pastel sticks a couple of years ago called Cretacolor that are water-soluble but also build up in an interesting way that creates a dense texture. I’ve also been making some abstract studies with them. I jump around a lot.

LG: You must use a lot of scanned digital images with your work, where do you get the most of your source materials?

CC: I collect stuff. Years ago, before the days of scanners, I would find images in magazines and books that were moving to me in some way and use them directly or xerox them if they were too precious to cut up. I have piles and piles of old xeroxes and new scans and prints taken from the internet. When I have an idea for a new painting, I rummage around through my piles of junk or go online to collect a group of images from Google that I can cut and paste to form a composition.

Some of the printed matter, like these Eadweard Muybridge ladies originally came from when I worked for the Robert Schoelkopf Gallery back in 1977. The Schoelkopfs, who also dealt in photography, had a huge collection of original Muybridge prints and I was always fascinated by them. One day when there was nothing going on at the gallery and I was really bored, I made a photocopy of one of them on the crude, early photocopy machine in the gallery. It had a fuzzy, soft and appealing surface about it so I photocopied a few more and took them home to start playing with them.

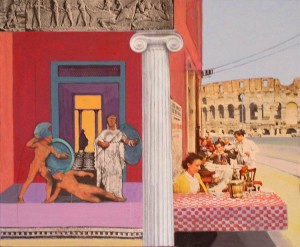

I spent a few years being obsessed with these Muybridge figures and eventually also started making sequences of the figures in motion. They became really important to me as a source for inventing little scenarios about figures moving through space. I took some of the Muybridge photocopies to Rome with me when I won the Rome prize and I felt an uncanny connection between these 19th century neo-classical figures and the sculpture from antiquity that was all around me. Eventually I started to juxtapose Muybridge people with ancient Greeks and Romans in architectural settings constructed of tickets, film boxes, candy wrapper–memorabilia of my daily travels in Rome.

LG: What was the source for a lot of the color schemes that you have here and the harmonies–were they sourced from anything in particular?

CC: Well in these earlier collages, because a lot of the materials were found, the color decisions were based initially on things that I just came upon day to day. That would be the jumping off point but later I think the color developed into a sensibility that was my own but also had to do with the color and light here in Italy. At the same time I made these collages, I was also working from observational still life and landscape, absorbing the visual world around me. They were also influenced by early Renaissance paintings from Tuscany and Umbria. That said, I have always had a predilection for very hot colors, dating back to my earliest still life paintings. At Cornell, I used to set up still lifes that were entirely red and pink. Sometimes, it seems like whatever I do, it just turns out red!

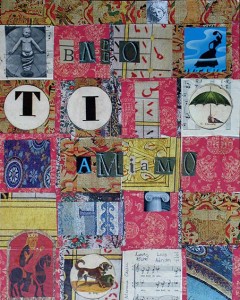

I have always gone back and forth between painting from life and painting from my imagination. I’ve made figure compositions that were very ambitious and difficult, trying to invent everything from scratch and then I have also always made these little collages. All of these different ways of working fed on each other in ways that I didn’t even understand at the time. Then in 1987, when my older son was born, and my time was extremely limited, I stopped painting in oil on canvas altogether and started to focus exclusively on collage. The collages gradually grew larger and more ambitious and eventually I found that they were exploring the same ideas from my figure compositions.

LG: Do you ever photograph things yourself to use for a collage or would it always need to be from a found source; do you make rules for yourself that you can only use certain materials or do you photograph something on your own if you need something specific?

CC: That’s a good question because my process has evolved to the point where I use a combination of found images and those that I photograph for specific needs. I didn’t do that in the beginning but now with the digital technology I do photographs things on my own quite a lot. I have no rules but rather try to follow my instincts.

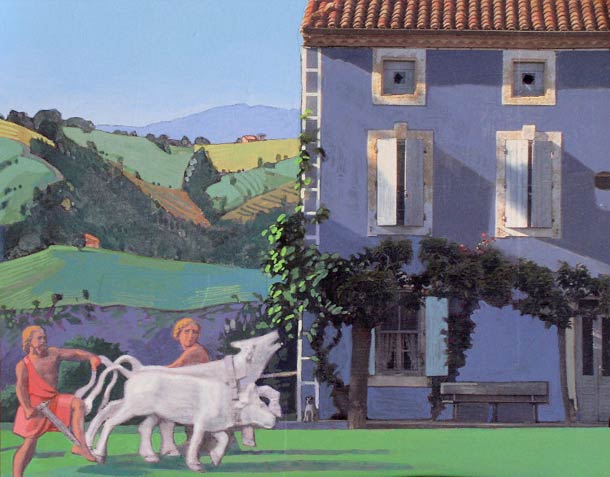

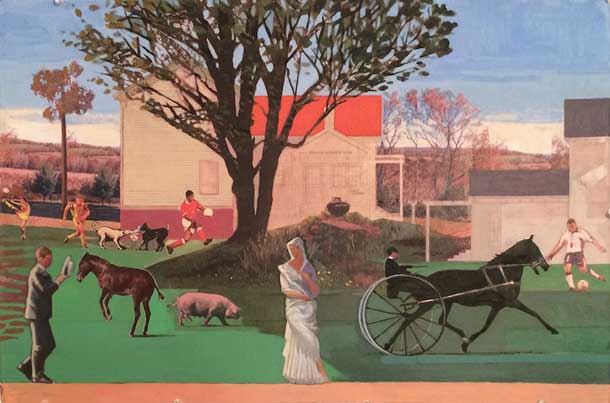

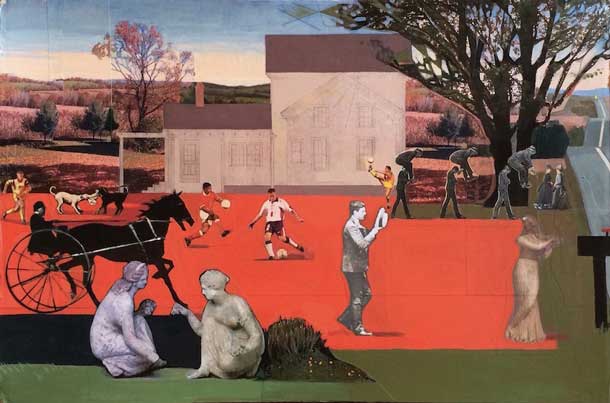

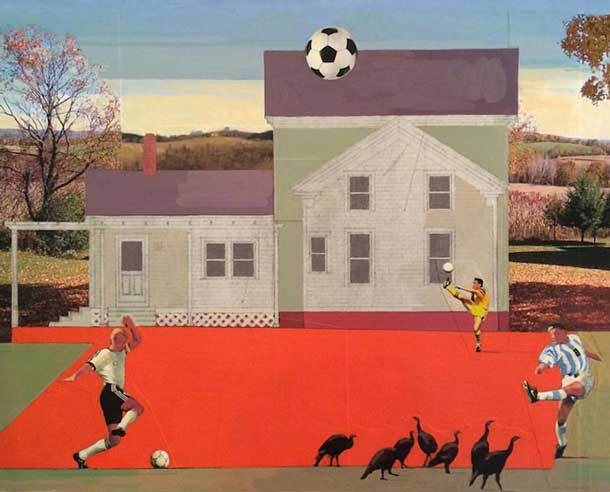

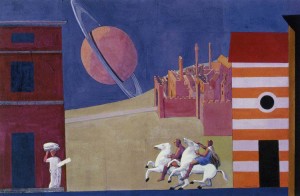

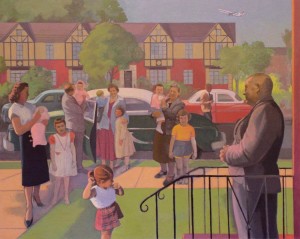

In these paintings, for example, the trees are from my own photos that were taken around our house in upstate New York, the soccer players are from an Italian publication about the World Cup and the house is a blue print made by an architect who proposed some renovations to our house in America many years ago. This series is a little reverie about our house in Upstate New York and our kids growing old. They both used to play soccer.

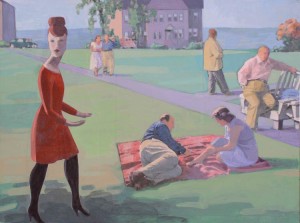

CC: These reproductions are of larger paintings that were made in America that are 5 feet wide. They are made from my own photos juxtaposed with sculpture by Elie Nadelman, which come from scans and the internet and Xeroxes from a book. So it’s a mix but I do use digital photography more and more these days.

LG: So you recently started looking out the window again, you have been painting a lot of still lifes, one of which is in this Zeuxis’ show that’s now at the Bowery Gallery. So you had a painting in the show that was done in the 80s?

CC: I think it was ’85.

Still Life, View of Olga’s House, 1984, 18×18″, oil on canvas

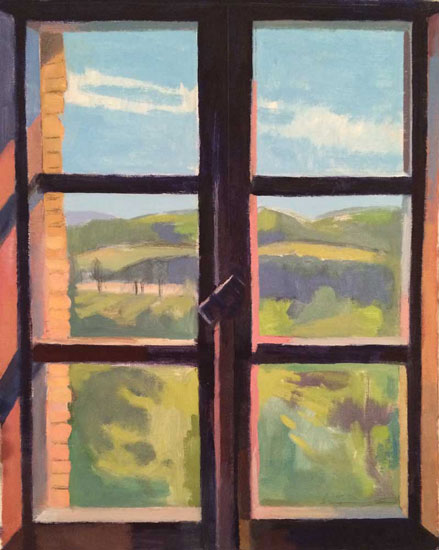

LG: I see you are working on some more paintings of “Out the Window”, presumably the same window.

CC: It is the same window, yeah.

LG: So how does that work feel; what are your thoughts about working on this kind of work simultaneous to your collage? Is there anything you can say about that?

CC: I have always, since Cornell, gone back and forth between perceptual painting and collage so it doesn’t seem odd to me. It sometimes seems to be a problem for other people because there is pressure in the art world to find a shtick and run with it. The collages and paintings from life are all studies, in a sense, experiments of subjects and formal qualities that interest me – experiments.

CC: Until this summer, I hadn’t painted from life since 1987 when our older son was born. I stopped working in oils for a while when I was pregnant and nursing, as I was nervous about the turpentine fumes and exhausted from teaching full time while pregnant and with a new baby. I started up painting again soon after he was born, but working mainly in collage and in short spurts. By the time our second son was born in 1990, I was something of a wreck, just so busy. I never stopped painting, but the collages became more important to me as a way that I could continue to work in the very limited timeframe available to me. The collages have always been an immediate way for me to explore my feelings. In a sense, they are a window into my subconscious. I start them spontaneously, intuitively picking and choosing images and forms that I see around me and juxtaposing them in odd ways, gradually developing a composition. Gradually, I came to realize that working on the collages was much more fulfilling to me than my figure compositions or still lifes in oil on canvas. In ’91 I had my last show at the Schoelkopf Gallery, right before they closed and I showed some of my collages alongside the paintings. Robert Schoelkopf, who was known as a dealer who showed realist paintings, was nonetheless, interested in the collages and said ‘Let’s show some of these along with the other paintings”. I had a wall of them in the show, and I felt pretty good about them. For years people had been saying to me, ‘These are interesting, why don’t you make them big?’ It seemed like sort of a stupid comment; just because something is interesting small doesn’t mean it’s going to be good if you make it big; it often doesn’t survive the change in scale.

But eventually, I wanted to expand on them, or at least try, so I worked out some technical problems to try and see if I could make them a little bit larger. I worked on Masonite for a while, and I started making them on larger panels and gradually just stopped working on canvas completely.

At a certain point I realized that I didn’t want to do paint from life anymore, I felt kind of bored with it; it felt like I was repeating myself just doing it out of habit. I wanted to do something that was going to be more challenging to me in terms of deciding what the content of the work was. Not that painting from life isn’t challenging, it’s very challenging. But I felt that for me, it had become habitual. And so I gradually moved into other areas and the collages grew bigger and bigger, to the point where I now make big collages that are also painted.

I have never stopped admiring perceptual paintings that are made from life but have felt at various times that it wasn’t for me. After many years, I grew to be nervous about painting from life again; I wasn’t sure I could do it anymore. Meanwhile, all the trees outside my studio window in Italy grew up so that painting my old view was not a possibility. I don’t like going out into the landscape to work; I hate the bugs and the intense sunlight, so I usually worked from the beautiful views out my studio window. But I couldn’t see anything anymore so I had the perfect excuse not to try. I felt like Sleeping Beauty; isn’t that the one where the forest grows up around her and she doesn’t wake up until the prince comes and finds his way through the forest?…

I spent many summers in here just doing my little thing, making collages. And then last year we got permission from the person who owns the land adjacent to ours to have all the trees cut down and I could see again. It’s been a couple of years now; I started thinking ‘I wonder if I could do this again’.

Olga’s House after the Earthquake, 1985, 20×18…oil on canvas

Then I was invited to the Zeuxis Beyond the Window show to exhibit one of my old window still life paintings. I thought, ‘Well, I might try this again; it used to be fun.” I like the painting that was exhibited. It meant a lot to me, having made a lot of those paintings out the window. So I set it up as a challenge to myself this summer, and here I am; I’m just doing it but I don’t really know what it means in terms of the future.

LG: Do you ever ask your husband, the painter Langdon Quin, for feedback on your work?

CC: Yeah, we look at each other’s work; usually not uninvited, but we do look at each other’s work. Is your wife a painter?

LG: No she’s not, but I often seek her advice anyway. She’s often reluctant to say much more than that’s nice, but often I try to guess what’s she really thinking; which is almost always a bad idea! However, sometimes my guesswork helps me to see the painting with a fresh eye.

CC: It’s very touchy, I know; sometimes I’ll ask Langdon what he thinks, and then when he says what he thinks I want him to be quiet because I don’t like what he says. I’m sure he feels the same way. But he’s a very good critic and I hope I am too. I’m honest, if I don’t like something I tell him and he’s the same. We might go into each other’s studios, but we don’t really say much unless we are asked because that can be disruptive.

LG: Yeah, having a critique about a work in progress is tricky; for me getting feedback is fine when it’s finished, but it’s harder to hear someone else talk to you about something you’re in the middle of working on. Their comments get into my head and it’s hard to dismiss it, even if what they said is completely off base and not something I think important; my mind starts to swing into a new direction and can be hard to turn off. So I don’t really like getting critiques on works in progress. Also, the person critiquing can often focus on things they are dealing with in their own work and not necessarily yours, yet they still go on and on about it.

CC: That’s a very good point. You have to be able to get your skin thickened to take criticism and be able to discard it if you think it’s not right for you. For a student it’s especially hard but important. I remember once, after I was out of school and I showed some work to Gabriel Laderman. I asked him for a critique, and he said ‘You don’t need a critique; you are an artist, you are not a student anymore.’ But then of course a few years later he gave me a scathing critique when I didn’t ask for it; it upset me terribly.

It is tricky, very tricky. And some people just like to shoot their mouth off; those are people I don’t like to invite into my studio. They just want to hear themselves talk; but you don’t always know who is going to be like that.

LG: So, you really like playing with the real world materials for your studies…

CC: Yes.

LG: So putting this together in photoshop with layers and stuff isn’t for you?

CC: No, no. I like the tactility of the collage. And I also don’t know how to use Photoshop very well. I can do elementary things in Photoshop, but I’ve never really learned how to use it. Every time I learn something, I seem to forget it right away.

LG: I can certainly understand the tactility for the final product… but I was wondering, that the computer might help with some of the labor of trial and error. But I can see the process itself, by seeing the collage elements move around in the real world might have a much different effect on your creative process than if you were doing it on the computer.

CC: Right. Yes.

LG: And I was just wondering if that was something that you had experienced and you chose to do this because you didn’t like the experience of seeing it on the computer, as if…

CC: I know. But the thing is, there’s no surface texture in Photoshop. You can create the illusion of texture but the texture is false. And what I really love about collage is the stuff that happens when you’re making it and painting over it.

LG: Right. The little highlights of the seams here.

CC: Part of what I really love about collage is the physical, material presence of the surface… It’s almost like a relief. And I suppose that’s why I’ve never made the effort to learn how to do it in Photoshop. There’s something in the process of the physical that is what really engages me. For me, the beauty of collage is in the process. I don’t plan them out and then execute them but let them evolve. That way, the making is an act of self-discovery.

LG: Well, I suppose it’s not so much about the image that you’re creating. That’s really the lesser thing. It’s more about the physicality of the whole…

CC: Yes, well it’s a combination of image and physical presence. These lines that are formed by the relief, become part of the architecture of the context for the people. I wouldn’t want to lose that. And this is one of the problems with photographing my work. That quality doesn’t come through in photographs.

They’re very tactile and very textured. I don’t work as thickly as I used to, but they still have a tactility, that has always been very important to me. I have always used really thick paint. I have trouble controlling myself!

LG: For many people these days there is confusion about what they’re seeing on a computer screen isn’t the real art. They completely miss out on the physical presence of the artwork, it is usually a very poor facsimile. Sadly, seeing it online can often mean they don’t bother going to galleries or museums anymore… because the computer is easier and quicker!

CC: Oh, I know! I have to tell you, speaking of digital images and process, I had an experience this year in my painting class, in which a girl – a very good student – was painting from the figure. I told the students that they could take a photo of the pose with their cell phones, just to have as a record after the model left, in case they wanted to refer back to the pose, but that they had to work from life. I always have them work from life. Well, I came upon this girl, with her iPhone in her hand. The model was standing, posing, the girl was at her easel, and she was painting from the little window of the iPhone, never looking at the figure.

LG: So, she took the photo right at the beginning–

CC: Yes. And I had a fit! My blood pressure was, you know, going through the roof. But then, I realized, well, she doesn’t know better, she doesn’t understand that working perceptually and trusting your eye to understand space and form in real time is different from copying a photo. When you’re copying from a photo it’s so much easier to fool yourself, if you’re just trying to get it right.

LG: Right.

CC: The photograph organizes everything for you but also prevents an inexperienced eye from understanding the space. I made her put the iPhone away and…she probably thought I was a crazy old lady. You know, it’s a great tool, for gathering and disseminating information. But then…I’ve banned them completely from my studio classes. No iPhone, no photos, no headphones, no nothing. I make them listen to my classical music station on the radio now and some of them complain about it.

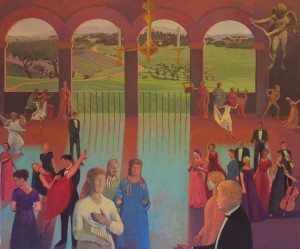

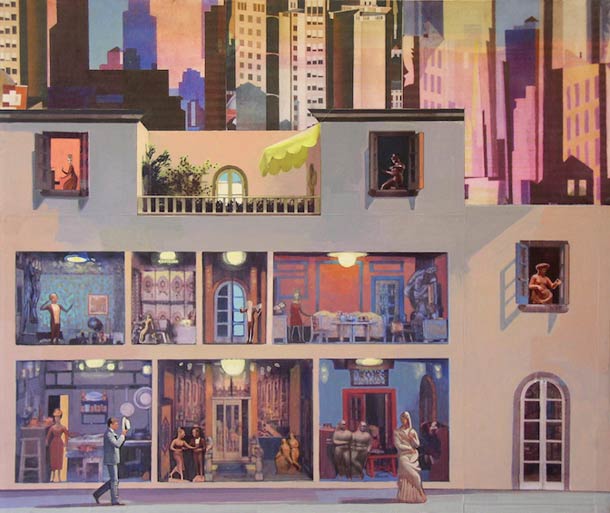

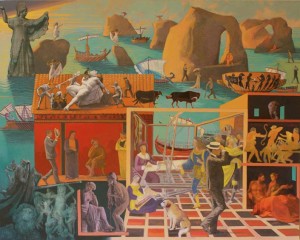

The Fancy Dress Ball, 2007, 40×48″, mixed media/oil on panel (Il Gattopardo by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa)

LG: How would you compare to… some of the other painters that you looked to, or other artists who do collage? Do you feel like you’re having a conversation with some others?

CC: Well, I’ve always loved Joseph Cornell. I looked at him a great deal in high school and college. I’ve always really admired not only his boxes, but his 2D collages as well. They are very, very beautiful and evocative. And I love Hannah Höch. I don’t know if you know her work as she’s not as well known. She was a German artist who was in the Kurt Schwitters circle. She was a very good painter and I’ve seen some very beautiful still-life paintings of hers but she is best known for her collages. She was part of the Dada circle and her collages are mostly of people, representational figures that are made from fragments of images from magazines. A lot of them were taken from anthropological magazines and images and they’re very, very beautiful and evocative. The color in them is especially beautiful. There was a big show of her work at the Museum of Modern Art quite a few years ago. And…who else? I love the cubist collages of Georges Braque, Picasso and Juan Gris. I admire the way that they mix collage with paint. I like many of Rauschenberg’s combines and of course I greatly admire the collages of Romare Bearden.

LG: You mentioned Kurt Schwitters.

CC: Yes, I’ve always liked his work. Except his work is not representational…Well, the famous ones are not representational. But I love his work. I love the materiality of his work, and the color.

LG: Why would not being representational be a problem?

CC: Oh, no! It’s not problematic for me at all. But it’s just that personally, I tend to be interested in representational imagery. Among the abstract collagists that I greatly admire include Anne Ryan and Mark Strand. I do sometimes work non-representationally, but I seem to always be pulled back to making pictures of things.

LG: Why do you think that is?

CC: It’s a good question and I actually talk about it a little bit in that essay I wrote about Guston. It was something that I struggled with in grad school. I have a lot of ideas about people, things I want to say about people, the places where they live and the way they relate to each other in those places. I am also moved by the way in which people relate to the past and their memories. Memories inhabit places as well and imbue them with meaning, both personal and collective. I don’t feel like I can do justice to this idea without the working representationally. My subject matter is risky, because when you put people in your paintings and start inventing stories about them, they run the risk of being corny. You know? I think some of my paintings are kind of corny. But the subject is what’s important to me. I’ve always been interested in subject matter and relationships.

LG: Do you have any concerns about staying far away from anything remotely being sentimental verses being something that’s heartfelt. How do you walk that line between having something that’s about real things, it’s not necessarily… I don’t see this as being ironic or anything like we were talking about earlier…

CC: No, no, they’re not ironic at all.

LG: But neither are they sentimental or completely formal. They’re just sort of personal engagement with this figure but I know there’s a lot of people that are concerned with that.

CC: I think that you’re touching on something really important because I’ve been accused of making sentimental work at times. I don’t want to be sentimental. I want my work to have sentiment in it, but not to be sentimental, which tends to be a pejorative term.

I feel that a lot of representational painters these days are afraid to paint about their genuine feelings or to engage in a genuine discourse about their lives for fear of seeming nostalgic or sentimental. Nostalgia and sentiment are definitely not “in” today. For years now, the norm has been to make paintings in which the subject matter is ironic, flip or shocking in some way. But there are also many artists out there that are working with heartfelt subject matter that is neither sentimental nor ironic.

CC: I once had a well known painter and art critic come to my studio at a time when I was making paintings and collages from photos of my family. The critic looked around at my work and first of all commented about how sentimental my work was, but then went on to say, “Do you know the artist Balthus? Now that your kids are older, you don’t have to make your work so cleaned up now, you need to put some sex in your work.” I was flabbergasted that he was so unable to consider what I was doing and the fact that I was trying to use subject matter in a personal way. He could only think about how spicing up my work with some sex would make me a hit in the art world. I was also taken aback that he thought what made Balthus’ work worthwhile, was it’s sexual content.

I love Balthus, but to me the sexual content of some of his work is incidental, it’s just a part of the story. I think he was a great painter whose work weds powerful formal qualities with keen observations of human nature. The great paintings that I love deal with feelings. They’re about people and their feelings. And good abstract painting is about that as well. When I think about great de Kooning or a lot of the abstract art that I admire most, it’s about feelings and human experience. So, I think that sentiments are okay.

LG: There’s a wide range of interpretation of about what sentiment would be, and I think that some people are looking for sentiment in all the wrong ways. For instance sex too of course is very sentimental. Even the crudest depictions of sex are sentimental, maybe not particularly pleasant sentiments, but it’s still sentiment. Maybe what is threatening is when a figurative artist is sincere or earnest about the subject matter.

CC: The problem I have with many well known contemporary figurative painters who aim to shock above all else, is that the titillating aspect of their work is in the service of a superficial kind of irony. There are often technical qualities to be admired about their paintings but the work is often mean spirited and insincere. I don’t ever feel that way about Balthus or the great so called “decadent” painters of the early 20th century such as George Grosz, Egon Schiele or Otto Dix. I think that in Balthus’ work, whatever allusions to sexuality exist are completely grounded in a painterly language and a kind of vision about life that is sincere. It’s interesting that Balthus was quoted late in life as saying that he regretted painting the Guitar Lesson. He claimed that as a young man, he trying to get attention. It worked. But I think that for the most part his work is genuine and inspired by true sentiment in the best sense of the word. It comes out of a real vision about the world through a visual language, which is why it’s great in my opinion.

CC: Scandals sell. Literal information that’s titillating, it seems, is easier to peddle than the more profound visual information.

The formal qualities of images communicate ideas, which is where painting has its real power. When a literal idea is imbedded in the formal visual language of a painting, that’s what really interests me. If the literal stuff is all you’re thinking about and the formal is left by the wayside, then it becomes sentimental or cheap.

That is actually related to what I’ve finally begun to understand about Gabriel Laderman’s teaching in the last few years. I think one of the most important things that Gabriel was concerned with in painting was the way in which formal qualities become the means to create a narrative. The actual construction of the painting – the composition, color and all of the formal qualities of painting (the horse’s head!) – tells the story in a visceral way, in conjunction with the literal information in the picture.

Larry: Thanks for all the work you put into these interviews. I find them very inspiring and they open me up to artists I may not otherwise come across. They make my day. Again, thanks. Joan Richmond

Wonderful interview.

Thanks, Peri. Regards –

Thank you so much for this.

I just spent a long time reading this essay/interview. I had not meant to take so much of my evening. I tried to stop and turn to the tasks awaiting me. But I could not. Wonderful questions and the best definitions/descriptions of an artist’s process I’ve ever read. Thank you both very much. Gracie mille!

Thanks, Susan. I’m so glad you enjoyed the interview. Thanks go to Larry for asking good questions and editing. Regards –

Larry, many thanks to you for this wonderful interview and for introducing me to Caren Canier. Her work is so evocative and rich – in content and in color. I do wish that I could see it in person to examine the texture and dimension that she speaks about. Caren’s method of working seems to combine the best of technical and traditional means, and the inclusion of some photographic elements makes it very contemporary. I love the color choices she makes, and while she prefers hot colors, they are also soft and very alluring. The red and pink together are dynamic and a difficult feat to pull off so well, but the combination evokes Italy to me, as well as Guston. Thanks again to you both!

Thank you so much for this interview. I have admired her work and loved reading about her thinking and process. Really enjoyed this!

Thank you Nancy for taking the time to write such a wonderfully written comment. Also many thanks to Michelle, Susan, Calli, Peri and Joan for also taking the time to leave comments. It means a great to me and Caren that our efforts are reaching people who appreciate this fabulous work and want to know more about the art and artist…

Yes, thank you for all of the comments and to you, Larry, for getting me to think about and articulate my process. Doing the interview was informative for me as well!

Thank you Larry for such an in depth interview with Caren Cranier. I was not familiar with her work, and like Nancy Natale, now will look for opportunities to see it in person…since the tactility of the pieces are hard to experience digitally. I related to so much of what she discussed.

“I believe it’s true because great painting transcends the literal to create metaphors that affect us deeply.”

“Nostalgia and sentiment are definitely not “in” today.” “I don’t want to be sentimental. I want my work to have sentiment in it but not be sentimental which tends to be a pejorative word.” A lot to rate to and to digest here. Terrific.

Hi Caren! There are so many thoughts that I have after reading this wonderful interview, that I’ve been waiting for a time when I am less busy to say thanks to you and Larry both! We were both at Cornell from 1970 – 1974 (I loved the landscape and university as well!) and so I will have to sit down and compose something at length that addresses many of the issues raised, but for now I want wish you a wonderful Holiday and I look forward to being in touch in the New Year.

How exciting to read in this interview that you met Colin Rowe while in Rome:

‘Judy introduced me to her friend and mentor, architectural historian Colin Rowe, who was working on his book, “Collage City” at the time.’

One of the better by-products of having Cornell’s art college joined to its college of architecture was that is allowed me to take advantage of attending numerous lectures there by Colin Rowe. These continue to exert an ongoing influence on my thinking and work.

As a part of my studio practice, I explore, in the medium of oil paint, elements that will appear as phenomenally transparent through the optical mixing of opaque pigments.

“Transparency may be an inherent quality of substance-as in a wire mesh or glass curtain wall, or it may be an inherent quality of organization-as both Kepes and, to a lesser degree, Moholy suggest it to be; and one might, for this reason, distinguish between a real or literal and a phenomenal or seeming transparency.” (‘Transparency, by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky)

Hence the dual phenomena of transparency – literal and phenomenal, real or seeming, substantial or organizational, actual or implied transparency.

Here is a 2013 post quoting from an obituary of Robert Slutzky, co-author with Colin Rowe of ‘Transparency’ on my website under ‘Visual Thinking’:

‘The essays in “Transparency” center on the ambiguity of the title word. “Transparent” can denote something that is literally see-through, like a window. But it can also denote something that is not, like the layered planes of a Cubist painting, discernible one behind another. Paint and canvas are opaque; the painter conjures transparency out of pure form. The illusion of transparency defines architecture. Painters have two dimensions at their disposal; architects have three. Transparency mediates between them. It can give the illusion of depth to a flat canvas; conversely, it can flatten a building into an abstract arrangement of geometric planes. Transparency helps the built landscape meet the eye.’

Obituary by Margalit Fox, Published May 7th, 2005 ‘Robert Slutzky, 75, Painter and Architectural Theorist, Dies’

Thanks again, Caren and Larry, for a wonderful interview.

Happy Holidays!

Ginnie

Hi Ginnie,

It’s good to hear from you! Yes, we were classmates all four years at Cornell. I still remember Jon’s drawings of a dead bird from freshman year and I recall working with you on the poster for our senior exhibition of full scale self portraits at the Johnson Museum. It’s funny how certain odd events endure in our memories.

Thank you for the quote from Robert Slutzky – it’s wonderful and I will read more on your website. I regret that I didn’t take better advantage of our connection to the Architecture program while at Cornell but it’s never too late.

Yes, let’s be in touch in the New Year and somehow get together. I recall that the last time we tried, our schedules didn’t mesh, but maybe we’ll have better luck in the New Year.

Have a very happy holiday!

best,

Caren

I’m looking forward to continuing the conversation with you! We are not that far apart and I’d love to take a drive over and have you here also. (BTW – I still have that poster – a kodalith silkscreen on silver paper of our senior class of 1974……somewhere in the warehouse!)

All best,

Ginnie

I enjoyed this immensely, thank you Caren and Larry. Caren, I think it is so admirable that you are always experimenting and being playful and true to yourself. The next time we see you in Italy, I would love to talk to you about some of what was in this interview.