I am pleased to share this email interview with the amazing NYC still life painter Barbara Kassel. She is represented by the Clark Gallery in Lincoln, MA and has had solo shows at the Hirschl & Adler Modern, NY NY., Maxwell Davidson Gallery, University Art Gallery, University of New Mexico, and Craven Gallery on Vineyard. She received her MFA in Painting at Yale University, New Haven, CT and a Diploma in Fine Art, Slade School of Fine Art, London in 1976. Barbara Kassel’s work can be found in numerous private, public and corporate collections

From the Clark Gallery website:

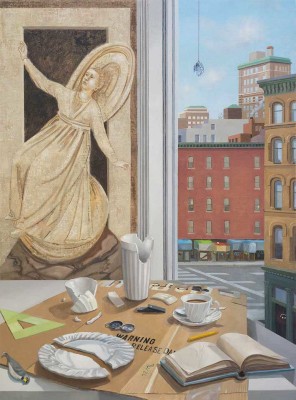

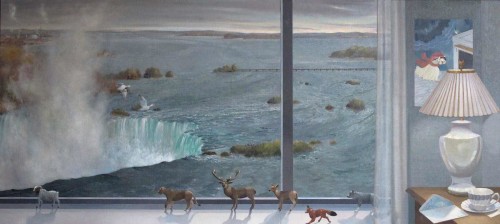

Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.

Larry Groff: Can you tell us something about your background? What lead you to become a painter?

Barbara Kassel: I was born in Los Angeles and grew up in the valley, in Studio City. I remember always drawing, painting and working on various craft projects. My older brother would use a red pencil to mark when I went out of the coloring book lines! I took my first art classes outside of school at a little frame/art shop on Ventura Blvd called The Flemish Art Shop. I painted Dutch like still lives with copal varnish as the medium, still lifes with watermelons and flowers and many a bright eyed furry kitten. I think that I came to painting as it was the most natural and satisfying way for me to be in the world. I liked the way I could create something, something that expressed the visual world and in a way, even early on, my interior life. My father had a serious heart condition and died of his third heart attack when I was 16. That had a profound effect on my life and how it unfolded. Immersing myself in painting and drawing had and continues to have a calming effect on me and helps me to integrate different aspects of my life.

LG: You studied at the Slade School in London for your undergraduate degree with R.B. Kitaj and Euan Uglow as a teachers. What was that like? How much of their teaching influences your work today?

BK: I went to UCLA first and that is where I met Kitaj who was a visiting professor teaching drawing. He didn’t teach at the Slade when I was there. He was rather terrifying at first. I was used to life drawing classes where there would be warm up loose gesture drawings and then the “long“ drawings of maybe twenty minutes. In his classes, the first drawing would last at least the entire session, or over several class sessions. He was a very intense teacher, concerned with really looking at what was in front of you. We became close personally and he said that if I wanted to be an artist, then I needed to go to an art academy, and London was the place to go. I spent part of a summer with him in London staying at David Hockney’s place. I would have to say that Kitaj was one of the most influential people in my life and we continued our friendship until his death.

The 4 years at the Slade, coming from LA, was a bit like landing on the moon. The city itself, so impressive, and so old compared with LA (which I love as well), the English accents, English life, English people, the amazing museums, the underground (I had never been on a subway) and no Santa Monica beach. The class I was part of had 12 students who would stay together for the 4 years. Entirely different from UCLA, which had thousands of students. My first day at the Slade was with the painter Patrick George who had us draw straight lines without rulers precise lengths in a large, rather gloomy skylit studio where in Augustus John’s time they used to draw live horses. I wondered what in the world I had gotten myself into. The other first year teachers were more conceptual in their approach, and more baffling. Like having to draw an entire interior on the side of a small chocolate with a pin, or making, as Bernard Cohen had us do, a drawing using orange juice. Stuart Brisley, a conceptual artist had us work in even more unconventional ways. During the subsequent years, we were allowed to take what courses we liked along with our independent studio work and art history at the Courtauld Institute. It was a mixture of classical and more contemporary teaching. I tended towards the more classical approach, taking classes with Sir William Coldstream (who came to the first class) of a 3 week session saying that “he would teach us how to paint a Euston Road School painting as if we were making an omelette”, Patrick George, and Euan Uglow who was also a very exacting teacher. My first experience with his class was drawing a bed spring for 3 weeks. Although I was not part of the small group of students who painted with this method exclusively, I was trained in the the Euston Road School of painting and drawing, which uses measurement at every second of observation. Everything is measured against an initial measurement, say the distance from the precise corner of the eye to the precise corner of an ear. You would use a red x to mark the measurements, which would be done over and over again using the thin handle of the brush, or a pencil sliding a finger up or down, or at times, callipers for measure. The set ups would be for at least 3 weeks and the students’ as well as the models’ positions were marked extensively in tape. This was to try and keep what you were seeing in place as everything came from the one initial measurement. Some of the students set up string or wire grids in front of their field of vision. The technique in measuring was “this is to that and that is to this….”. No focus on making an object, or what it was. It was an observation of the relative distance between all aspects, tone to tone, color to color that built up the image. It was painstaking and almost meditative, but never actually boring. It is a way of drawing and looking that I have incorporated to this day. A way of forcing a slowing down of looking and responding. While at the Slade, I also took a course with Frank Auerbach who was equally exacting, but in an entirely different way. By the end of the 3 weeks session, my one drawing looked like a torn up rag of paper from constant erasing. At one point in my drawing late on, Auerbach came by and said, “Now this is going well!, let’s have it off” and promptly erased my drawing.

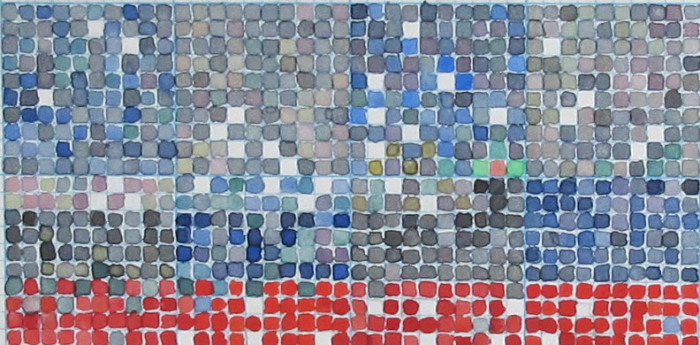

A printmaking technician, painter and friend at the Slade, Roy Osborne introduced me to color theory with Seurat being center stage (Seurat and the Science of Painting, by William Innes). He has just published another book, Books on Colour 1495-2015 History and Bibliography. I did hundreds of color studies from life using graph paper and recording what I saw in small spots of color. I would also weave canvases using webbing to have physical squares of colors. Landscapes, interiors, still lives, and models were my motifs. I would often work on the same view, but in changing times of day and light. I still like to paint a same view or set up with a change of day to night.

While at the Slade, I was accepted to Yale’s Summer program at Norfolk. I arrived there from London about 10:00 at night, the studios were already abuzz with students stretching their canvases. I was jet lagged and I think very much in shock. The first group critique was the afternoon of the first day, in contrast to the Slade where there were never group critiques that I can recall. I had a grid watercolor that had maybe 30 squares of color from a landscape I was observing, while other students had several paintings. It was an art boot camp. But what I also found was that there were instructors there who appreciated my way of working (Louis Finkelstein, Arnie Bittleman and Philip Guston who visited for a day). I have friends to this day from that Norfolk summer.

LG: During your graduate studies at Yale you studied with Al Held and John Walker, two important abstract painters. Did it matter they had such different approaches – hard edge vs. painterly, expressionistic abstraction in their teaching? Did you have a positive experience at Yale? Did you paint abstractly back? What lead you to paint representationally?

BK: I never painted what I would call pure Abstraction. My work was always based on perception, inside and out. Al Held and John Walker thought that I was an abstract painter and they were hostile and the opposite of helpful. The people who actually contributed to my education at Yale would be William Bailey, Andrew Forge and Gretna Campbell (I was her teaching assistant) along with professors of art history and my fellow students. During my first year at Yale, I turned away from the grid color studies into painting what I had left behind and missed so much in London. Loss is a major part of my work and is an important part of what draws me to visual art. Creating a world or a vision that might be physically gone, but is still present in my mind is often what speaks to me.

LG: You were selected to be among a group of painters representing the United States at the 1984 Biennale in Venice, including such painters as Eric Fischl, Richard Bosman, Jedd Garet and April Gornik. This was a great honor and must have been a terrific boost to your career.What was that show was like for you?

BK: I had entered a juried show in Baltimore in 1982 where I was living. It was juried by Marcia Tucker of the New Museum, who I knew nothing about. She picked my painting for a prize and asked to buy the painting after the show. I came up to New York to meet her with the painting and slides of my work. About a week later, as I was getting the car fixed, my then husband called me to say that New York galleries had been calling the house. She had presented my work at one of her lectures at the New Museum about unknown artists and that was what spurred the interest in my work. I came to New York to meet various dealers and ended up being represented by Kathryn Markel, who was very enthusiastic and wonderful to work with. I had my first 2 solo shows with her and then she closed her New York gallery, and I joined Maxwell Davidson Gallery. Some years later she opened her gallery in Chelsea. Marcia Tucker was the curator of Paradise Lost/Paradise Regained:American Visions of the New Decade. I was a fellow at Yaddo when I was called to the phone to learn that I had been chosen for the Venice Biennale which was thrilling. I had painted from time to time in Venice, and it was wonderful to be able to go again and paint.

A New Life, 10×20 inches oil on panels (triptych)2002/3

LG: Your work in that show seem ethereal, imagination-based interiors looking out onto the exterior world. Your work today sometimes explores similar themes but with a different sensibility and style. Even though your work today is more realistic it still seems very imaginative and playful. Can you say something about how your work changed from what you were doing then to now?

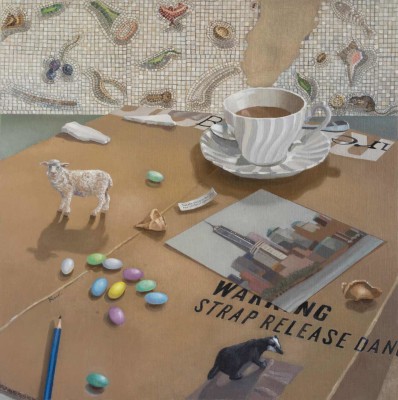

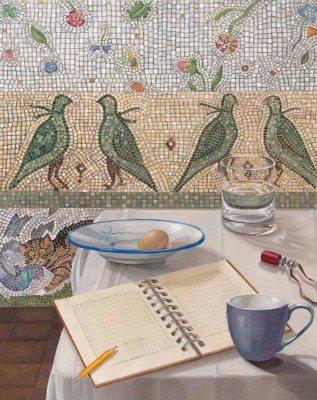

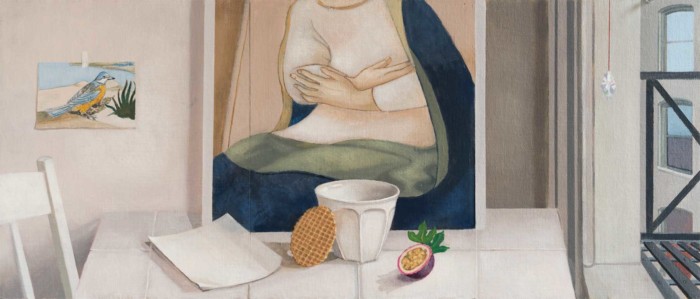

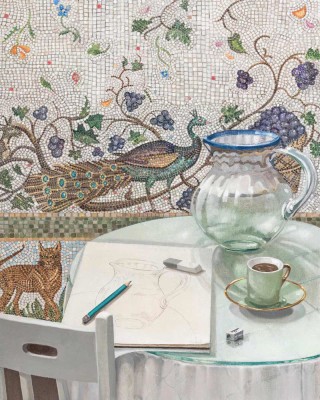

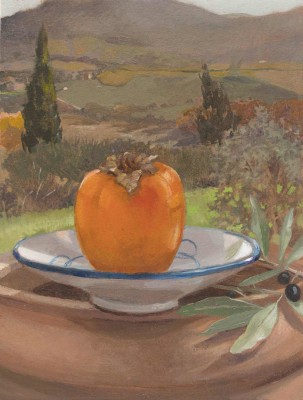

BK: The paintings that I worked on during that time were based on reality and dream. I have been and am still intrigued with Quattrocento paintings with predellas. I liked that there were different but related narratives going on within the same painting. You would have the main scene, let’s say, the Madonna and Child, and then below, you might have the story of the Visitation, or the Journey into Egypt. I began to incorporate predellas into my work, using them in a not so dissimilar way. I might have a time of day shift, a shift of waking world to dreaming world, a narrative shift, etc. The paintings in the Venice Biennale were part of the “Paradise Regained” section. “Dusk” came directly from the interior of the apartment I was living in Baltimore, with a dream like (and often in my dreams, there is water) predella. “Stromboli” came from studies that I painted while in Stromboli. I did and continue to do extensive painting while traveling. I bring a sketch book and either watercolors, or oils, or both. I just returned from 6 weeks of painting this fall in Italy. I’ve painted in many parts of the US, Europe, Israel, Mexico, China, Japan and in much of Southern and East Africa. I’ve painted studies that I sometimes use in making studio paintings. I continue to be influenced by travel. I am particularly interested in the frescos and mosaics of Italy. My newest paintings use more of mosaic and fresco imagery, which harken back to my earlier paintings in many ways.

Why did my work change? Because my life did and continues to do so. I paint where I am both physically and psychologically.

LG: How much are you referencing Greek Mythology in your Hermes Paintings series? A Wikipedia entry about Hermes says: – “Hermes is a god of transitions and boundaries. He is quick and cunning, and moves freely between the worlds of the mortal and divine, as emissary and messenger of the gods…” I find this interesting in that many of your still lifes play with the 2D and 3D space, mixing them up – slipping back and forth between the boundaries of these worlds in a fluid manner… Please tell us more about this series.

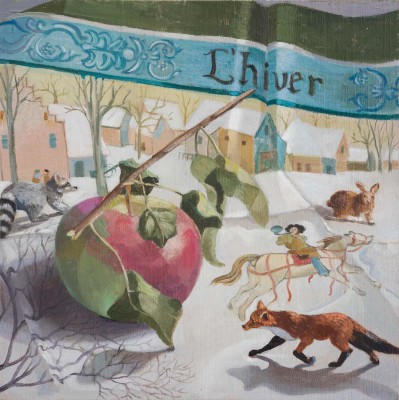

BK: I have loved Greek Mythology since I was a child. Yes, I am referencing some Greek mythology in these paintings, but mainly they are more personal narratives and symbols that play out for me on the scarves. A close friend gave me my first Hermes scarf for a birthday some years ago, and that was the beginning. I bought a beautiful lilac Hermes scarf on Ebay and the thought occurred to me that it would be lovely to paint. So my first Hermes paintings were on a scarf called Des Fleurs pour le Dire. I set up a cow figurine and a simple white bowl. I think that part of what drew me to paint set ups on the Hermes scarves, was the freeing up of my recent palette of more muted colors. These were colors that I rarely used in that way and they had a kind of joy, play, whimsy and lightness to them. I have about 20 Hermes paintings now, and quite a collection of Hermes scarves from Ebay. Not for the feint of heart!

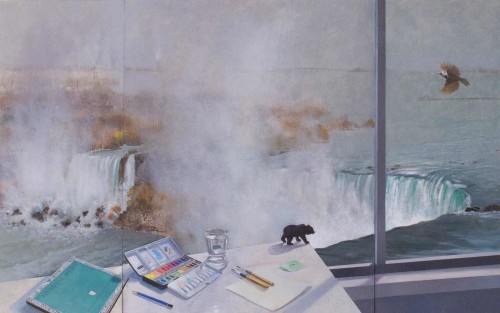

LG: I’m intrigued with how you expand and contract some of your interiors, adding or removing panels, keeping the composition open for changes as needed. Many of your paintings have very strong horizontal and vertical divisions, like with the windows, tables or architectural elements, which break up the picture in interesting ways. The separation line between the panels fit in well with the geometry.

BK: I often start with a single panel and it may grow into multiple panels as I expand the view, the narrative or the formal composition. Often as not, I will be nearing what I think is the end of a painting, when another attached panel (or 2, or 3, or 4) attached seems to form another option. It is sometimes crazy making and the panels can be combined in different ways. Recently, I have been doing more extensive composition planning on the computer and ordering specific size panels. But sometimes, those too become multiple panel paintings My largest painting was 11.5 feet long and comprised at least 6 panels. Bear Turns Corner too started as a single panel. So I know to order multiple panels at a time with at least one dimension being the same for this possibility. I almost always explore the possibility of adding panels. When painting abroad, I travel with sets of same size panels or oil paper.

LG: Do you use a golden section or similar compositional structure or do you have a more intuitive approach? What sorts of things are you concerned with in your compositions?

BK: I often use dynamic symmetry as a compositional tool. The golden section is itself dynamic symmetry. With dynamic symmetry, you can start with any rectangle and create compositional structures. With compositions, I am concerned with how the eye moves through the painting and with the balance, or lack of.

LG: What are your most important considerations when you start making a painting?

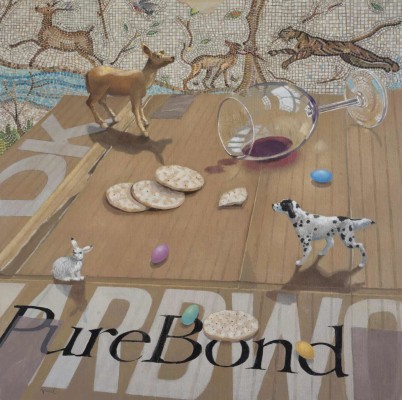

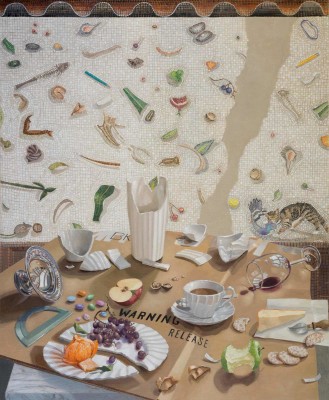

BK: That depends on the painting. It is always visual. If it is plein air, it usually has to do with the scene, the light, color, shapes etc. If still life, the objects, their relationship, the light, color, what they mean might be what draws me. Or coming upon something by chance, like what I was working on this past spring and summer, paintings with Roman mosaics, Unswept, Warning, Pure Bond (and continuing in the fall with Birdcall and Peacock). I had set up a stillife, and one of my cats jumped up and caused the backdrop to fall and break a number of ceramic pieces. That caught my eye visually but also metaphorically. Sometimes it is a narrative impulse that has me starting a painting. A celebration of something, like my marriage inspired a number of paintings (Two is for Joy, Proposal, Wedding Cake, etc). Sometimes it is for mourning (All that Glitters, Transition, Mourning Glory and others). I spent the year after my mother’s death painting about mourning with some of her things. I think that by painting what is going on in my life, it helps me to live in it.

LG: Can you tell us something about your work process, how important is observation in your work? Do you work out a careful drawing on the canvas prior to painting?

BK: I have a very direct perceptual approach to plein air paintings and also paintings of more simple still lifes. My studio paintings are more complicated and layered in their approach. But they always start with something I have seen while awake, or dreaming. I sometimes work on paintings over a period of years. I might get an older painting back and find myself completely repainting it.

Since meeting my husband, the photographer, Jed Devine in 2001, my paintings have become more immediate in the sense that they are based more on where I am physically as well as emotionally in the world. Prior to that, I made paintings based mainly on travel to other places. But for the past fifteen years I have worked more in places that I know intimately and where we share a life. We live and work in a loft in NYC, in a studio on Martha’s Vineyard, and until a year ago, in a rustic house on a small island off the coast of Maine for 2 months each summer. We share a space, with each of us having our own areas, but which often overlap. When I first moved into the loft in NY, I found that I needed to paint myself into my new life there. I worked directly from the interior of the loft and the views from the windows. In the larger paintings that include both interiors and still lives, I work from different set ups and then collage them. Working this way allows a fluid play between the objects and their surroundings. My objects are chosen for their formal properties and their ability to evoke narrative and symbolic aspects. Recently, Jed has been photographing my process of painting and looking at his photographs changes how I view my paintings and often leads to changes in the paintings themselves. He designed a book called Musings which is about how our work is part of an ongoing conversation.Link to the book Musing.

When I am not with a computer, I draw in pencil more extensively. I don’t usually do detailed compositional sketches in pencil, although I have spent years drawing observationally and continue to do so. Recently I have been doing more composing on the computer using Photoshop, where I start with an idea (which often comes from one of my paintings or a study I am working on) and then builds from there with sometimes countless variations. Finally I stop all that and start on the painting with a basic working composition.

And of course, that usually changes early on in the painting. So it is a fluid situation, changing during the process and often spinning off another painting or panel.

I use mainly oil primed linen mounted on boards as my surface. I work on a toned ground with a light loose charcoal drawing, or a drawing on the panel based on the composition I have printed. I then block in the major areas. As the painting develops other objects may appear, and earlier objects may disappear. I may change the time of day, or the color of a wall, or change the scale of things. An almost collage technique.

LG: What kind of brushes and types of paints do you tend to use? Do you paint directly or with a more layered, indirect approach? Anything special or unusual about your technique?

BK: I use a mixture of good sable brushes (flats and rounds) and some bristle brushes. I like to use a variety of oil paints, like Holbein, Blockx, Williamsburg, Graham, Winsor and Newton, Old Holland. I love trying out a new color and one of my great pleasures is going into an art supply store and coming out with a new naples yellow, or a delicious new madder, or splurging on a new cerulean blue.

LG: The article about you in American Artist said that you start your painting with a middle tone and then work out the broad composition and drawing in charcoal, you then work more specifically with colored pencil. I’m curious how that you work with the pencil over the charcoal, isn’t the charcoal lines too dark and prominent or do you somehow erase the charcoal lines before drawing in colored pencil?

BK: The vine charcoal gets lost right away in the blocking in of the painting. I use color pencil during the process of painting to draw on the panel. To re-establish composition, sharpen an edge, etc. I also sometimes use color pencil if I am working out the dynamic symmetry of major compositional elements.

LG: The color relationships in your composition are marvelous, can you speak a little about how you think about color in your work?

BK: I tend to use color in a natural instinctive way and am concerned with the painting being visually beautiful. I think that the years of studying how colors interact with each other and being intermixed is also very much part of what I use in painting.

LG: It is easy to get the impression that Beauty ranks far less than the idea for many of today’s post-modernistic painters. Does this concern you? What does striving for Beauty in painting mean to you?

BK: I don’t care what other post modern painters think about Beauty. Beauty is a very subjective and personal experience that for me has less to do with the actual subject matter and more to do with it’s transformation through formal means. So yes, I strive for beauty in my work.

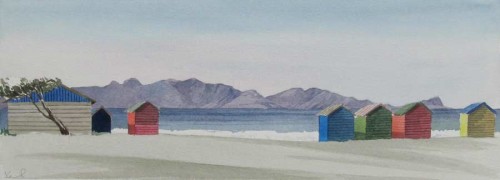

LG: You have traveled extensively and make watercolors but don’t often show them. However, Watercolor Magazine had an article about your watercolor in Spring of 2010.

where the article stated that you

“…had been making watercolors on her travels for almost four decades but has rarely exhibited them. “They are all part of my work,” she says, “trying to see and take in what is in front of me, or in my imagination. A kind of training in looking and translation.” The watercolors sometimes form a basis for a later oil painting, but they are usually made for the simple pleasure of looking. “So much of painting for me is about being present where I am, sometimes physically, other times emotionally,” says the artist.” …

“I was once traveling overnight on the Nairobi-Kampala train,” recalls Kassel. “Instead of taking 24 hours it ended up taking 40. I drew and painted tiny watercolor studies from the train in the cafe car, which was packed. I had a crowd of people all around, some standing on tables to get a view watching me paint, laughing and talking, fully engaged. Once I relaxed into it, I had a great time, and it seemed like they did too.”

Art can be a great communicator and it was wonderful to be able to communicate with the people on the train with no spoken language at all. And best of all was the deep pleasure of recognition and laughter between human beings. Art has been with us from the start.

In Kenya a baboon leapt up on my table and took my watercolor palette away. It was shocking. Once it realized that it wasn’t good to eat, it returned it and instead took my coke, and I returned to my painting, both of us happy, if a bit shaken.

If we were to judge from the paintings, the artist succeeded in keeping her calm, clear vision even amidst this mayhem. Like most painters who work in plein air, Kassel has had her share of adventures. “I find that often when I am traveling and painting on-site, people are very curious about what I am doing, and it starts a kind of dialogue, which sometimes can be interesting, especially if I don’t have to talk,” she says. “I’ve painted in China where whole neighborhoods have come out to gather around me, pointing out what I am painting, questioning each other, and often laughing, which is wonderful. Once, while I painted by the side of a dirt road in the Samburu area of Kenya, two Samburu warriors came out of nowhere to watch me work. They smiled and laughed a lot, especially when I drew them…

LG: I find your travel painting fascinating and wonder if you might speak more about how (or if) these quickly done on-site studies influence or inform your studio based oil paintings

BK: I both love and hate to work on site. The studio is so much more private and comfortable. But there is something that is particularly invigorating about working outdoors, or while traveling which gets one out of one’s comfort zone, and also introduces a complete unknown. I have used studies for parts of studio paintings and have used studies sometimes done years ago in paintings. The process of working directly from something in pencil or paint stays with me in a visceral way. And working onsite makes you present in the moment.

LG: What advice would you give for someone starting out in painting still life?

BK: I would say start simple, and perhaps stay simple! Set something up you are interested in painting, but not too interested in the objects themselves perhaps. A composition that speaks to you with it’s shapes, interrelationships, color and tone. Start by calming down, by looking and responding visually to what is in front of you. Relax and let time go. Work with the relationships between things, not the things themselves. One tone/color against the next. Let the painting develop and take it’s form.

Barbara,

I really appreciate your commentary on your amazing training in London and at Yale…what a fabulous experience. Your work is wonderful to look at even in reproduction and I look forward to standing in front of your work sometime soon. Beautifully realized.

Barbara,

The breadth and range and thoughtfulness and beauty of you work is greatly inspiring. I have seen much of your work but learned much more from this interview. Thank you for your dedication, depth, and insight.

What a Fabulous interview! So much depth and insight into your history and work process.

Loved seeing the variety of paintings. A real visual and psychological treat! Wonderful read!!!

I enjoyed your whole interview and especially the schooling you had in England, where you learned precision. i did wonder whether your last name Kassel was somehow connected to the german city? I ask that because my wife was born there and Mahler created his initial great works there.

Hi Barbara. I read your interview with great interest and enjoyment. Your descriptions of painting on site in Africa and China are amazing. Would make a good book, with your travel paintings as inspiration. Also like hearing about your experiences at Slade, and your encounters with those famous personalities. Good to read about your process and your ambitions. Good to know more about you after all these years.

Barbara Kassell does not live to paint, rather she must paint to live.

Someday, soon, her genius will out …to the world. Not unlike Vermeer.

Truly.

i feel very fortunate to have lived with a few of Barbara Kassel paintings over the years, and feel they are almost zen like in their effect on me. Thank you for the wonderful interview

Barbara is a wonderful painter. Thanks for the interview and the images!

Gorgeous paintings- so rare. So refreshing to see work beyond Jeff Koons. Will visit again!

Hi Barbara. So pleased you are still painting so well and traveling too. I lost my studio last October (2015) and have caught upon some writing since. Nice you mention me. And that you upload your new work on Facebook. I’m giving a talk at UCL next month and showing some paintings (PICS 2016 conference).