by Tina Engels

I visited the studio of Anne Harris and had a peek at the some of her new paintings and a glimpse of some drawings that did not make the cut for her last exhibition. We discussed her process as she pushes further and deeper into what she feels is true in her painting, excavating and digging into the various stages until a physical palpable physical reality emerges.

Anne Harris has exhibited at venues ranging from Alexandre Gallery, DC Moore Gallery and Nielsen Gallery, to the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute, The Portland Museum of Art, the California Center for Contemporary Art and the North Dakota Museum of Art. Her work is in such public collections as The Fogg Museum at Harvard, The Yale University Art Gallery and The New York Public Library. Grants and awards received include a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and an NEA Individual Artists Fellowship. Harris currently teaches in the BFA and MFA programs at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is vice president of the board of the Riverside Arts Center and chair of its exhibition committee. She also is the originator of The Mind’s I—a collaborative drawing project designed to investigate the complexities of perception and self-perception through drawing. The first iteration of this project took place at Julius Caesar Gallery in Chicago, Nov.-Dec. 2012. Harris lives with her husband, the photographer Paul D’Amato, and their son Max, in Riverside, IL. —- from Anne Harris’ bio on her website

Tina: The early work makes it clear you are a gifted observer. How has your work changed over time?

Anne: I don’t think of what I’m doing as observing. That implies an objective point of view. Painting for me is subjective—interpretive, felt out. But regarding the early work: I’d fallen in love with northern Renaissance portraiture. I was trying to understand how subtlety led to intensity, and how detail and description could be used in a meaningful way—not as illusionistic indulgence, but as something essential. I also was trying to understand how those paintings were invented. Rhythm, simplification, the character of the light (luminosity emanating from inside the painting) figure/ground tension, the compression of form—all those things are fictitious inventions.

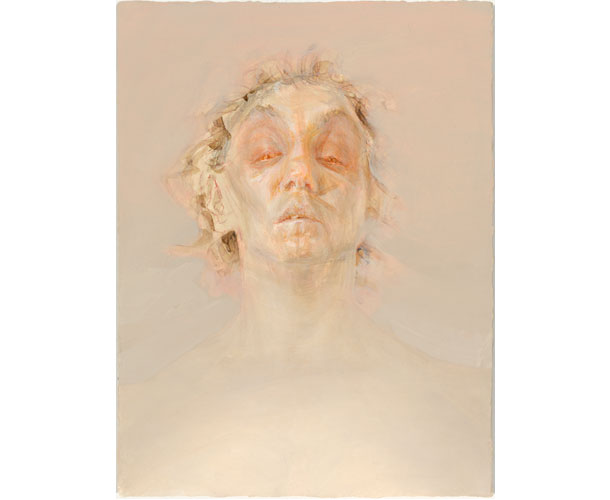

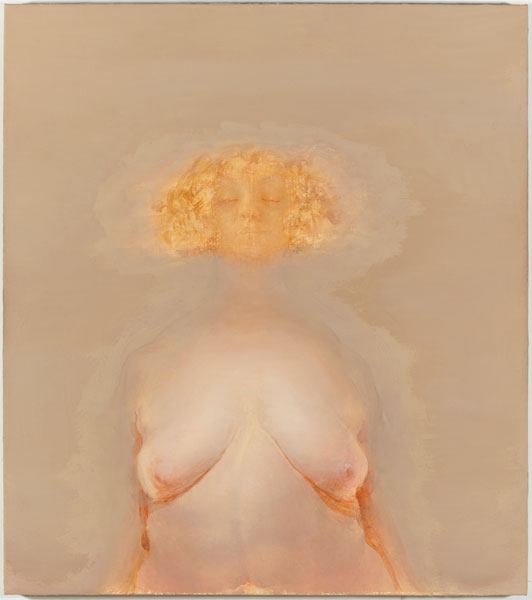

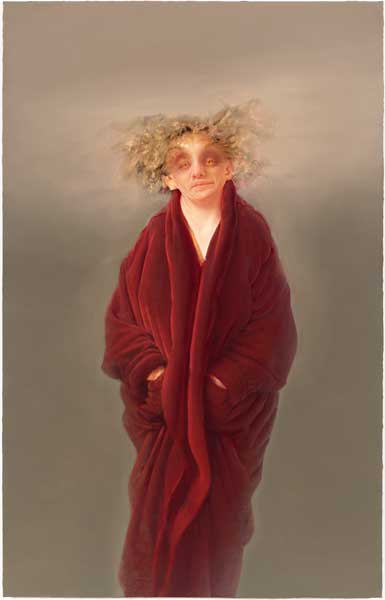

Since then, my paintings and drawings have gradually opened up, become softer edged, with areas of focus shifting. Lately, sometimes, the figures are translucent or transparent, functioning more as ground than figure.

Tina: How is the perceptual in painting relevant to your work?

Anne: I think painting is fundamentally perceptual. It’s experienced in a sensory way. I don’t mean just seeing. Touch, movement, memory, imagination and emotion—all can be understood as perception, and all are involved when making paintings and looking at paintings. Painting from life, which I do, is another aspect of this. We each perceive the world differently: information passes through our senses to our minds, through our bodies to our hands, which then touch a surface to make marks that are specifically ours. That said, when I’m painting, I’m always looking at something. It may be that I’m just staring down the painting trying to figure out what it is, what belongs there, what’s next; or I may be looking at myself, or at a model or at other drawings or paintings in my studio.

Tina: What role does drawing play in your art and what is its relationship to the painting?

Anne: I draw a lot. I tend to have periods, particularly after finishing a body of paintings, when I only draw—drawing binges. Drawing is more natural for me, it tends to be in front of my painting, pulling it along. One of my ongoing struggles is trying to figure out how to paint more like I draw, to allow the painting to grow naturally, to evolve rather than be knocked about… painting is just really hard.

I have a definition that I use for drawing—an organization of marks that transform a ground. So a mark on paper transforms that paper into light, air, weight, movement, etc. A mark can be anything and the ground can be anything. This can apply to a broad range of media, to any subject, representational, abstract, 2-D, 3-D. The key is the transformation. That’s the magic. It’s what I look for in art.

So, I think about drawing all the time. Lately, I’ve been using paint on paper, but have been thinking of them as painted drawings. I’m paying close attention to how the mark transforms the ground it sits on, thinking less of the paint as an overall skin. I’m trying hard to set a mark down and mean it, to not think of it as something that will disappear under layers of paint. This is different for me, difficult.

Anne, in her studio, April 2014

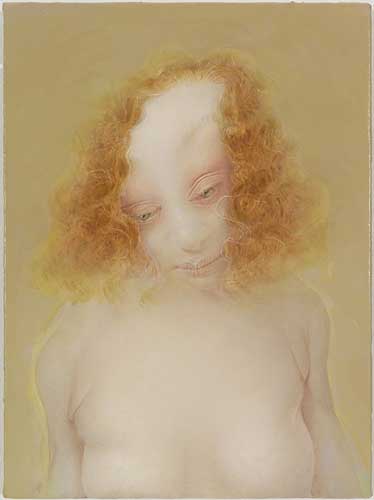

Anne Harris, Portrait (Old Neck), 2001

Tina: If you could work with any artist, past or present, who would it be?

Anne: I’d like to be invisible in Rembrandt’s studio. Just let me watch.

Tina: It is interesting to say you would watch. Your figure paintings appear to look, or are aware, but are not hiding from us.

Anne: I’m interested in what it means to be looked at and what it means to look back, particularly as a woman over the course of a lifetime. I like that you say the paintings are aware. That’s a nice way to put it.

But… if I were able to visit Rembrandt’s studio… I’m boringly literal when I fantasize. So, I want to be invisible because I imagine a 21st century women standing in the middle of Rembrandt’s studio would cause a ruckus. Really, I just want to spy on him, to see exactly how he does it. Let me spy on him for months. I’ll be very quiet.

Tina: Do you refer to the paintings as self-portraits?

Anne: I don’t call them self-portraits (I tend to title them “portrait”), although I’ve looked in a mirror at some point for pretty much every painting, but they are self-portraits in that some aspect of them comes from me (probably the anxiety part). I want them to have the presence of a portrait, the presence of an individual, and the sense that they contain something beneath the skin—self-consciousness, emotion. But I’m not so interested in describing exact likeness.

Tina: Do you look at any particular painters for inspiration?

Anne: I look at a broad range of painters, as well as other artists. The list is long—I keep adding to it. It starts with the Venus of Willendorf. It includes everyone you’d imagine I’d like, plus some surprises (maybe)—I love Ad Reinhardt, for instance, and Agnes Martin, and Robert Irwin. I respond to work that mesmerizes me. It’s not about the subject. It’s an experience, a feeling—hypnotic slowness. But then I also really like Joan Snyder. And her paintings are a kick in the gut.

Tina: Are you trying to illicit a specific reaction from your audience?

Anne: I hope for some reaction! No reaction would be bad. But I can’t presume to control what the audience is going to see or think or feel. I’m not comfortable dictating the meaning of the paintings. That comes from the conversation it has with you, the viewer.

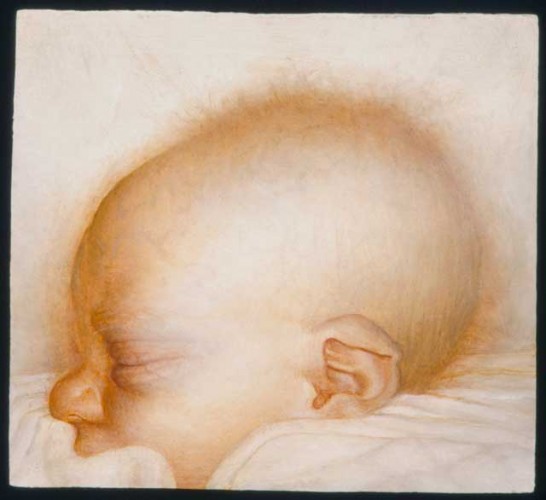

How to Draw Yourself Out of a Hole, No.#53, 2005, Water color, oil, graphite on mylar over paper, 12 x 10″

Tina: In the studio, we looked at a stack of drawings that didn’t make the cut for her last show. What criterion is required for you to exclude this work from exhibition?

Anne: Actually, that’s not quite right. The drawings we looked at were from an earlier body of work called How to Draw Your Self Out of a Hole. They weren’t excluded from this show, but preceded it. They’ve been shown in other places.

As far as something “not making the cut,” I find that I continue to be very good at making bad work. My worst work now is as bad as anything I’ve ever done. Sometimes the work fails because it’s overly facile—a glib facility demo—or mannered. Stupid, affected. Unfortunately, sometimes I don’t realize that’s happened until it’s too late; the work is out in the world and there’s no recalling it. Sometimes it fails in blatant beginning-painting ways—I kill the light; the painting is dead. Usually though I’m not excluding finished pieces from an exhibition, but rather, they hit the trash or land in a dark drawer months earlier, and that’s that. Every now and then, I revisit something I thought was bad, and realize it’s good. But usually, bad stays bad. I should throw more away.

Tina: Can you talk a little about your process?

Anne: I work with oil paint using very few colors. I don’t have a precise plan or system, just things that I generally do. I’ll often start with raw umber and lead white, working in thin washes. Temperature shifts occur right away that suggest color and so I’ll add colors as I need them, and often another kind of white (lately I’ve been very into Williamsburg zinc buff). The color functions relatively, that is, the hues can’t be named—it’s subtle, a product of layering and of side-by-side color interaction. Certain colors will seem blue or violet in the context of the painting but are actually mixtures of raw umber and white. I work in thin translucent layers, like skin. Sometimes I might introduce a very intense color, but that usually winds up buried in the strata of the painting. It definitely changes things. There’s a certain kind of light and certain kinds of grays that just can’t be created with opaque paint. Usually I get into trouble at some point and the painting goes somewhere that surprises me. Sometimes, that somewhere is a black hole I can’t get out of. If I’m lucky though, the surprise leads me to the point of the painting.

Ed Note: Painting Perceptions offers many thanks to Anne Harris as well as Tina Engels for their generous contribution of time and energy with this interview.

This is all quite powerful…I keep going back over the pictures of the paintings and get very drawn in to each, some more than other, but very drawn in. I imagine watching Anne Harris painting, and would love to be in ‘her’ studio and be invisible watching her paint. Glad I had this opportunity to read and see this blog. Tx SG

I very much like your work the tender way yo paint the faces of these character s as they emerge