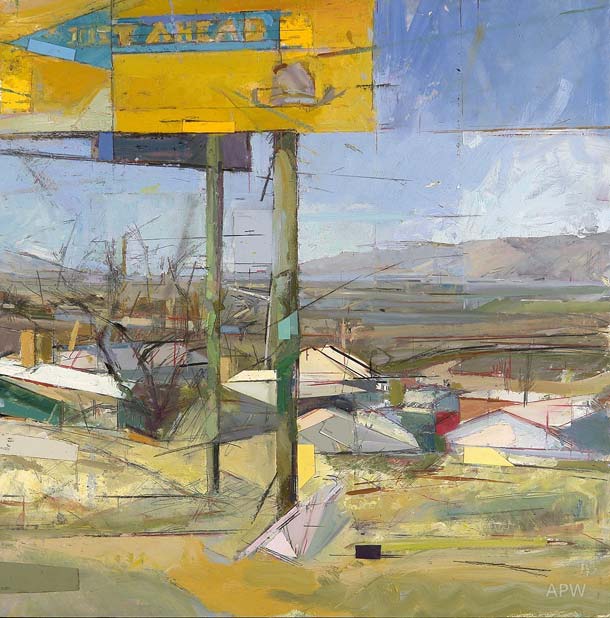

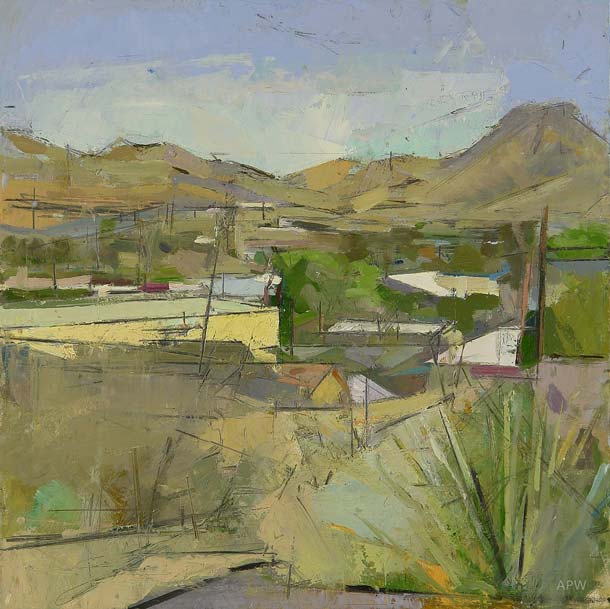

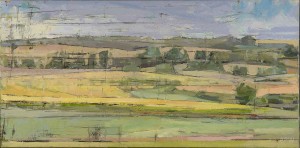

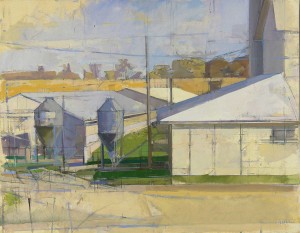

I had the pleasure to interview, Andrew Wykes a British painter who currently professor of painting in Minnesota at the Hamline University in St. Paul. He has been painting at the The Ballinglen Art Foundation in Mayo, Ireland for three summers and is teaching a workshop there this summer (see this link for more info) Wykes studied at Richmond upon Thames College, Epsom School of Art and Design and an MFA in painting from American University. He has taught art for thirty two years in schools and colleges in the UK, Belgium and the US. Andrew has shown his work nationally and internationally including London and in New York. He is a recipient of three Minnesota State Arts Board Initiative Awards in 2009, 2013 and 2015. He was awarded a fellowship at the Ballinglen Arts Foundation in Mayo, Ireland, and is featured in the document film “Painting the Place Between”. He is represented by the Groveland Gallery in Minneapolis, MN and The Water Street Gallery.

Larry Groff: What were your early years like as a student and as a painter? How did you become a landscape painter?

Andrew Wykes: I have always painted, since I was a boy. I thought everyone did that, only to find out at Art College I had done an enormous amount of work from my past and the other students had made very little.

Back in the 1970’s in the London and the South East of England where I grew up, it was a different world in term of attitudes and outlooks. The landscape was less spoilt and over developed, much has changed since then and not all for the good.

I took a foundation course at Richmond upon Thames College in London in 1978, it was in the days before austerity took a grip. It was a year of exposure to many different art practices, fine art, painting, drawing, figure-drawing, illustration, graphic design, learning how to draw letters and proper spacing. Also learned about book-binding, photography, and an array of printmaking techniques. This was before computers. It was mainly aimed at commercial arts but if one were to be a graphic designer you would have had a really strong foundation to work off. It was rich experience for me.

I still wanted to paint and make fine art, so I then took a three-year Diploma course at Epsom school of Art and design – Just out of London. By then Maggie Thatcher was in power and steep cuts had robbed the art colleges of resources and many were closed. We felt it, as worked in cold studios with little direction. I was lucky to have the other keen students to work with and our teachers were hanging in the London Galleries – so to speak.

LG: Who have been some important influences for you and why?

AW: At the age of fifteen, I was struck by the Constable paintings in the National Gallery collection in London; shadowy, dramatic with an inherent poetic quality. I felt more was going on than mere depiction. The drive behind was on one level a personal experience of place and yet the work holds a pantheistic view of the world. I treasured the dusky tonal colors of horizons and trees; subdued chrome greens and gray pallid Prussian blues. These had a direct and recognizable characteristic that I too saw and enjoyed in the landscape. In reproductions of Constable this does not come over. Also, what impressed me, and still does, is Constable’s determination to get it right. While employing a controlled, well ordered direct means of working, the goal to make a parallel of what he sees in real time and space, actual on a flat surface and to give immutability.

There also so many other painters I look at but in fact it is formal aspects of music that is more influential now. In my studio at Epsom I remember frequently listening to such contemporary music as Brian Eno’s “Ambient Four, O Land” along with other obscure orchestral works. But before that I was always drawn to the landscape around me. It was and still is my solace.

LG: What are your most important considerations in looking for a view to paint?

AW: I don’t really look for a view to paint. I used to. But I feel there is too much to look at. If I was pinned down, I would say it is to do with nerves and personal preferences that come out of a whole internal catalog of memoires, geographical and autobiographical and desires to acquire the experience of the seen. I find looking and returning to the same subject over numerous sessions rewarding. I tend to go deep into a subject—not wide.

LG: How much does observation inform your work?

AW: Observation is vital. I have always got great enjoyment from seeing. I feel privileged that I have this gift to see. I also think it is to do with retaining the child’s eye of the world before label’s for object’s disguise the subject.

To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees. (Paul Valery)

Painting is all about seeing. It is learning to understand what one sees in formal terms of course. I am not concerned with depiction or likeness. I am battling with my preconceptions and how to make a spatial world work on a flat surface.

Painting is abstract. It about universal feelings. But on a less formal level, active looking has all the rich trappings of meditation or prayer or oneness, the joy and surprise during a rare moment of lucidity.

LG: What can you tell us about your process? Anything special about your painting technique? What paints do you put out on your palette? Anything note-worthy about how you approach to painting outside?

AW: The way I work outside changes. It is all to do with practicality. Ideally I would like to have a place where every is set, up and can stay there undisturbed for an unspecified amount of time while I come and go.

But there is an attraction to stripping everything down to the bare essentials. I grew up very near to Windsor Great Park in the UK. I would walk several miles to my location. Everything had to be carried. Small back, easel, food, tea and the appropriate clothes for the weather.

My palette is a mess, no organization. Often more paint on me than the palette! I am clumsily and naturally get paint everywhere—food too!

A lot of my painting now, is made in the studio from memory and photographs. Here I am able to work with very strict systems or processes. I give myself rules throughout a piece. For example a lot of the bigger pieces are made with many rolls of masking tape, my hands and paper towels. I work the paint into the canvas with my hands. No brushes (I never clean them and they go hard so they are useless to me) lids fall off the tubs of paint and get lost in the piled debris on the floor. I don’t have time to clean up and be tidy. That detracts form the urgency of painting. It is a bit of a performance I suppose. I can’t teach that stuff, we all find our managerial solutions, what works best for one does not for another. Although I would not recommend my approach!

LG: Many of your paintings seem to have a very active and assertive surface, with energetic marks that emphasizes the horizontal and vertical relationships and underlying grid. Can you tell us something about what you are thinking about with regard to the surface and marks?

AW: I have a strong sense of composition structure balance and space if what I see around me. I am irritated when see a building that is off-plumb. There is so much structure in Constable and of course Cezanne and also Frank Auerbach. But the structure and build up of lines also asserts the pressure or tensions between planes and spaces. The surface left on the canvas is the residue of a process of addition and subtraction of paint.

LG: I understand you teach at Hamline University in St Paul, MN. Do you teach landscape painting or is primarily studio based training? Is landscape painting something that is taught in the universities or it something people need to figure out more on their own?

AW: I have taught for over 30 years and I’m constantly figuring out ways to deconstruct the students assumptions and fears about painting. I teach Drawing and Painting from a variety of visual stimuli, both in and outside the studio. I also make work that is more conceptually based without visual stimuli to draw from.

On the whole students are overwhelmed by the idea of landscape it is too esoteric for most of them. Some are interested, they tend to be well grounded in others area of school as well, they seem to understand analogy and the different between loneliness and being alone—which painting is. Perhaps it takes an older soul to love landscape.

LG: What is the painting scene like in Minnesota? Do you miss being near the major art hubs like NYC or London?

AW: Minnesota has good support for artists in general. And what I have found is artist tend to connect with each other more so than back in the UK. Minneapolis is not what I would call a painting city. Some of the attitudes of what is hip verge towards rather dull installation art. I feel galleries and schools are showing and teaching from a fashion that’s gone. It’s either a derivative of 1990’s installation work or crass sentimentalist landscape. Good painting is dismissed for not having content. I have never been one for fashion. In London painting is painting without apology. Yes, I miss London, I had a privileged upbringing being exposed to so many free public collections; cutting edge shows and good art schools.

LG: You are leading a landscape painting workshop at the Ballinglen Art Foundation. August 4th – 12th 2015 in Ballycastle, Ireland this summer. Can you tell us something about how you go about teaching your workshop there? What is the attraction to Ballycastle for landscape painters?

AW: I was awarded a fellowship at The Ballinglen Art Foundation 7 years ago and this is my third time going back. The landscape in that part of Mayo is quite extraordinary. It is like going back into the past there are moments when I feel I am back in the 1960s, some of the cars and road signs… I suppose it’s the unpretentious, undeveloped land. Stone walls and fields that have been that way for centuries. For a painter you are accepted and uninterrupted. The weather is so changeable from one hour to the next, for me it heightens the sense of drama and urgency to get something down.

It is challenges the way one works and that is a good thing.

LG: What matters to you most in painting?

AW: How can paint address the sensation of being in a space so as to rival the experience of the place itself? This is a question of timelessness that continues to haunt me.

The experience of painting a landscape “on site” can bring me feelings of refuge or unease as well as melancholy or hope—feelings that hold me in the present moment. I am aware that the landscape itself in unresponsive—the love I feel for it will not change it from its position of indifference.

Lovely work. ‘Bisbee Afternoon’ is particularly terrific. Thanks for another great interview, Larry. You are still leading the pack 🙂

So glad to see this interview, Larry! We are lucky to have him here in Minneapolis.

I enjoyed the paintings and the talk a lot. my question is this. I often hear the term colour spot, or colour value. It seems to me that in your paintings you apply that kind of thinking very beautifully. you try to define the spots with so much sensitivity. I would like to know what the term colour spot or colour value means to you. thanks.

Good interview and interesting work that explores seeing. Is there a link to the documentary?

Beautiful work. These paintings activate my brain when I look at them–very exciting to the eye.

I was at Ballinglen in June for a week. I was familiar with your work through reproduction so I found this interview very worthwhile.