Amy Mahnick is an artist living in Brooklyn, NY who has been painting observed still life setups of sculptures she makes out of household plastics and other materials. She has shown work at the Nancy Margolis Gallery in New York as well as the Richard Heller Gallery in LA. She has her MFA from the New York Academy of Art and a BFA from Michigan State. I would like to thank Amy for her patience and time in putting together this email interview.

Larry Groff: Can you tell us something about your background? I understand you got your BFA in Sculpture at Michigan State but then went to The New York Academy of Art for your MFA in painting. Why the change from sculpture to painting?

Amy Mahnick: I wasn’t really changing disciplines so much as trying to accumulate all the knowledge I could, and have a different experience. I was the first person in my family to study art so everything was new to me back then and I embraced it all. The sculpture program at Michigan State focused on ideas and what was happening in the contemporary art world, and I really enjoyed it, but by the end I was craving something more formal and with a deeper connection to the past. I remember taking a trip to the DIA where there was a show of Tuscan Drawings from the Uffizi, and Andrew Wyeth’s Helga paintings. I was captivated by both of them, and knew then, that that was the direction I wanted to explore next. So after graduation I signed up for drawing and figure painting classes at the community college and kept re-enrolling until I applied to the Academy.

LG: You’ve been painting still lifes of your sculptures made from household plastics that you have transformed in various ways for the past several years. What led you to make and then paint these forms?

AM: A few things seemed to come together around 1997. After graduating from the Academy I continued studying at the Art Students’ League with Harvey Dinnerstein, but after a couple of years I felt the urge to move on. I had immersed myself in the technical side of painting since moving to New York and was beginning to realize how I had neglected the artistic side. So I left the League and started setting up more conventional still lifes, and occasionally getting friends to pose, or hiring a model. But I also started going to the Picture Library and checking out and painting images of infant birds in their nests, seen from above with their mouths wide open and waiting to be fed. I was on my own in the city for the first time without any attachments to school or close family and I was trying to find my way, so I was drawn to their images of vulnerability, tentativeness and dependency. And around this time, one day while rinsing out a paper milk carton, I saw something similar to the bird’s beaks, a sort of simplified, cubist version of them in the spout. It was a very “ah ha!” moment, because although I had been studying the figure and was committed to painting realistically, I was also always very drawn to abstract painting, and realized that I was, at heart, a still life painter. So the milk cartons were the perfect discovery in that everything I loved came together with them. I loved their simplified, geometric forms, that I could work 3-dimensionally preparing them as props, and how they had similar potential for embodying the psychological and emotional content of the birds.

Pink 2007, oil on linen, 16 x 18 inches

Whip 2006, oil on linen, 36 x 28 inches

Alarm 2006, oil on linen, 18 x 18 inches

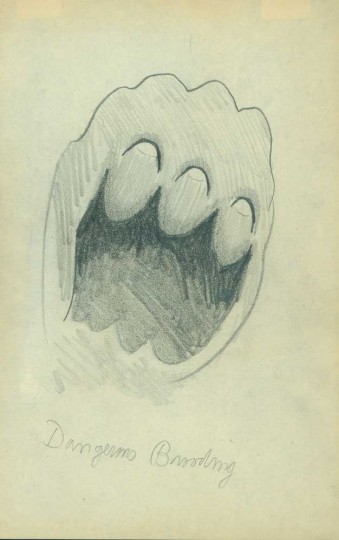

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967)Dangerous Brooding, 1917 China marker and graphite on paper 8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

LG: There seem a division between work that explores engaging, emotionally charged abstract structures like we see in Pink, 2007 – Whip-2006, Alarm, 2006 and then the more works that are more like anthropomorphic portraiture and akin to figurative painting. In both of these directions I don’t get the feeling you’re trying to make a statement about recycling or repurposing the voluminous amount of disposable plastic in our lives. Instead, it’s almost like you’re being a talk therapist for trash – giving opportunities to the non-verbal to tell their story. You seem more interested in the personal than political. Charles Burchfield in his “Conventions for Abstract Thoughts” made a drawing dictionary of sorts, where he gave various shapes definitions of certain emotions. I get the feeling there could be something similar going on with the shapes in your work. Is this something you can talk about or does it all happen more on a visual level. Can you tell us something more about the meaning in these paintings?

AM: This is almost all right on. Being a still life painter, I’m always looking at and responding to the objects around me. And in the city, where people tend to take out a lot of their food, and where the sidewalks are lined with mounds of brightly colored plastic on recycling days, I can’t help but notice it. So my work has never been about the environment, in a political sense, but I am interested in the cultural significance of my materials. Part of the reason I work with them is because they are overlooked, mass-produced and disposable. And it’s not that I want to give voice to them so much as that I see a correlation between them, and the way we live our lives. When I’m shaping the plastic into sculptures what I think I’m trying to do is infuse organic life into them. I want to break down the resiliency of their machine-made forms. But that’s the big picture. What draws me into the studio and compels me to make anything at all is more personal. I make the work that I do to express what I can’t with words. And I love the Conventions for Abstract Thought. I feel like my sculptures are a 3d equivalent to them. Though I’m not providing a key, the way he is, to the meaning of the forms as they appear in paintings, I seem to be building up a lexicon of sorts with some of my individual sculptures.

Pieta 2003, oil on paper, 11 x 14 inches

FlitCraft 2007, oil on linen, 9 x 7 inches

Untitled 2009, oil on linen, 12 x 10 inches

Siren 2007, oil on linen, 36 x 36 inches

studio shot

LG: Do you have rules or limitations that you set for yourself with these figurines? Like you can’t use glue or can only have a certain type of plastic or you must paint the sculptures exactly as you see them in the painting? Is it important to leave some vestige of the forms previous incarnation as laundry detergent container, etc?

AM: There are no rules as far as materials. I use whatever it takes to get them to work and hold them together. And more and more I’m wanting for there not to be any vestige of what the props were originally, at least not in the paintings, because it leads people down the wrong path. It’s what tempts them into thinking that my work is about recycling or Pop Art.

LG: Are your figurines finished sculptures that you show along with your paintings? Do you ever reuse or reconfigure finished figurines with new still life set ups?

AM: Yes, sometimes I reconfigure them, either for a new piece or to make them fit better into whatever it is I’m working on at the time. And I exhibited them as finished sculptures a few years ago, alongside my paintings, but it didn’t work so well. Having them there gave away part of the mystery of the paintings. Also, they were showcased as an ensemble in a plexiglass vitrine, so they were elevated in a way. They looked beautiful, but the thing is, it’s their humble materials and imperfections, the beads of glue and cracked, uneven plastic that give them part of their meaning. I think those traces reveal something about my process and motivations, that I had to make them for the activity itself, for the search and the cutting and gluing and piecing together, as much as for the paintings. Displaying them, at least in that manner, tended to camouflage this aspect of them.

Untitled 2010, oil on linen, 12 x 14 inches

Untitled 2010, household plastic and water, 9.5 x 7 x 3.75

The Taming of The Shrew 2008, oil on panel, 8 x 10

LG: Do you paint these all from life? Can you tell us something about your process? How do you go about beginning a painting?

AM: I work exclusively from life now, but my process has changed and evolved over the years. I have used photography to greater and lesser degrees, and also alternated sessions of working out of my head with working from observation on the same piece. And in the past year or so, since I began teaching, I rediscovered a love for drawing. I never had the patience before, or felt like I had the time, really, to spend drawing and sketching as a preliminary to painting. I always wanted to just dive right in. Now I spend time doing both, and making small oil studies on paper. It’s a much better way of understanding and becoming acquainted with what I want to do and my final canvases always begin more fluidly. And I begin those on a white ground prepared with Holbein’s Foundation White. So far it’s still available…And I’m terrible at composing paintings because I’m always focused on the prop, so I usually sketch out my placement first, on tracing paper, then pounce and transfer the sketch before blocking in my lights and darks with a turp wash.

Untitled 2002, oil on paper, 11 x 14 inches

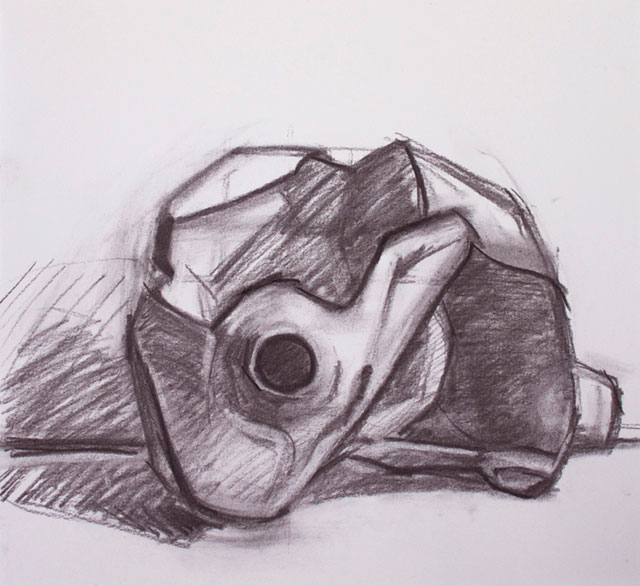

Priestess 2012, charcoal on paper, 13.75 x 11 inches

LG: What are you thinking about when you go about setting up the color harmonies in your paintings? What colors do you put on your palette?

AM: I’m thinking about either the mood of the painting or colors I associate symbolically with viscera, reds, pinks and yellows etc.

These are the colors on my palette. I add some, and substitute others, depending on my set-up.

Cad Yellow Medium and Dark, Titanium White, Yellow Ochre, Raw Sienna, Burnt Sienna, Cad Red Light, sometimes Medium, Alizarin Crimson or Magenta, Flesh Ochre, Raw Umber, Burnt Umber, Ultramarine Blue, Cerulean Blue, sometimes Prussian, Permanent Green, Viridian or Sap, and either Cassel Earth or Ivory Black, but rarely.

LG: Some sculptors these days are using computer 3D sculpting applications to make their sculptures with. These virtual sculptures can then be turned into physical sculptures with 3D printers that will reproduce them in plastics and even metals. Do you think something like this would ever interest you as something to paint? Or are you only interested in painting plastic that has been reconfigured from pre-existing objects.

AM: Yes, I’m only interested in working from what I find. If I ever make a sculpture that’s not a construction, I’ll build it up with clay or cast it in plaster or some other material with my hands. Too much of the meaning, and pleasure, of my work comes from the direct, physical interaction I have with my materials and working alone in the studio.

The Gold Cell 2009, household plastic, packaging material, water and string, 8 x 7.5 x 7 inches

Pierrot 2010, oil on linen, 10 x 7 inches

LG: Some of your figurines evoke theatre or TV characters in some way such as in your Pierrot, Queen For a Day, Honeymooners and Marilyn. Other figures leave me guessing if they might reference other paintings. Could you tell us a little more about your figurines relation to other art?

AM: Some of my titles are problematic in that they are as highly subjective as some of the paintings and not as easily decoded, as they might suggest. In “Honeymooners” for example, the figures looked to me like they were waving out from a picture postcard captioned with “Wish You Were Here”. It doesn’t have anything to do with the tv show. I should probably change that one as the reference is confusing. For Pierrot I was thinking of Watteau’s figure in the Louvre, and his particular posture and presence, his humility and not necessarily the character from Comedia dell’Arte.

The titles are associations that come to me while I’m working and the figures begin to take shape. I’ve rarely started out by trying to make a particular figure. When I have, I’ve learned to accept that it’ll never come out as originally planned because I work intuitively. The meaning in my work always arises out of the materials rather than being imposed on them.

LG: I’ve read that Poussin and Tintoretto both made clay and wax figurines placed in miniature stage sets to study the play of light and shadow and to work out compositional ideas. I find this intriguing and I’m curious to know about other artists who’ve sculpted studies for their painting or perhaps go even further, like you’ve done, to make the sculpture the subject of the painting. Have you looked into the history of this? What artists have influenced you in this direction?

AM: I haven’t looked into the history of this and I’m not familiar with these examples, but I’m sure that I would love them. I love artist’s studies. I vaguely recall other painters working from dioramas like these at the Academy. But I really just think I work the way that I do because of what appeals to me. I like 3-dimensional form, and I like intimacy and painting. It’s why my compositions are usually so simple, with only one or two figures rendered up close and on a small scale.

I painted lots of trompe l’oeil architectural ornament for close to 9 years to support myself and I think that job was really satisfying for the same reasons, because it appealed to my form sense. The ornament was always rendered either as plaster, stone, or gilt, and acanthus leaves, the mother of all decorative motifs, are very expressive. Depending on how they’re drawn they can be either elegant and graceful or sinewy and creepy.

Marilyn 2009, oil on linen, 15 x 16 inches

Honeymooners 2009, oil on linen, 18 x 16 inches

Before You 2009, household plastic, 8.5 x 3.5 x 3

LG: Who have been some of your most important influences especially in relation to your current work?

AM: Morandi and Picasso are the big ones that I return to time and again. And there’s Louise Bourgeois, Lee Bontecou and Alina Szapocznikow’s early sculpture and drawings. On the lighter side there’s Kathy Butterly, Ken Price and Euan Uglow. And there is Deborah Butterfield, who, to me, is sculpting empathy as much as horses. Carpeaux’s maquettes at the Met are some of my favorite things in the world. I love the intimacy of their scale and the how every tiny piece of clay is a record of human touch. Most all sculptor’s maquettes appeal to me for this reason, sometimes more so than their fully realized work.

LG: I read a quote from you stating; “I give meaning, purpose, and beauty to something that people would traditionally rather not see,” “I want to bring these figures to life, so I bathe them in light, surround them with vibrant color, and paint them with close attention and empathy.” I love what you say about painting with close attention and empathy. Can you tell us more about what that means to you in your practice?

AM: If I don’t feel a real physical and emotional connection to the subjects I’m working with my painting is going to fail. And the act of painting itself is a communion of sorts rather than a detached observation for me. There’s a very direct, mutual dependency between the props and I, that’s established through my line of sight, where they become animated and reveal something through their contours and gestures etc. and in return give me something to respond to. The sculpture I’m painting now is a shell made of fragments and lined with pink felt that elicits an emotional response when I see it from a particular point of view. It has an immobilized energy that’s sad. It’s sort of writhing and arrested at the same time. But it only works from particular points of view. From others it’s nothing more than a pile of plastic and felt.

Untitled 2008, oil on linen, 14 x 11 inches

Collide oil on linen, 11 x 10

Aorta 2013, charcoal on paper, 11 x 12

Thanks for the introduction to Amy’s paintings. The technique looks exquisite and the colors are very pure and beautiful. The contradition of such beauty and discarded plastic is wonderful. I enjoyed hearing about her developement as an artist and her personal techniques.

Beautiful work: so nice to see more of your paintings and to learn about the background of you and the work! Great interview. Thanks for sharing. Tasha

Actually, I must add that the convulsed milk carton drawing in charcoal is also extremely compelling! Really love it.

Tasha

Amy’s a wonderful painter. Their is a surety and lightness of touch with the paint handling…not too fussy and not too haphazard, that is very pleasing. I especially like the paintings where it is hard to figure out what you are actually looking at (the taming of the shrew, siren); it gives the work an air of mystery and formal abstraction that keeps you circling back through. So great to hear her story and keep up the good work!

Beautiful arresting work, Amy! Thanks for sharing your thoughts….really interesting to me. ox Joan

Enjoyed Amy’s interview; made acquaintance with her early on, found both her and her work inspiring, intelligent, and aesthetically pleasing; am currently interested in recent 2022 activirties and projects,, as well as reconnecting with her, grateful if anyone might know know where, who, or how.

Thanks,

Gregory k